What They Wrote, What They Saved: The Personal Civil War

This exhibition features diaries, letters, and firsthand accounts from four years of Civil War that offer intimate glimpses into the lives of men and women affected by the strife. The words were written in parlors, hospitals, and schoolrooms; around campfires and on tossing ships; to and from mothers, brothers, and sweethearts, teachers, soldiers, and sailors.

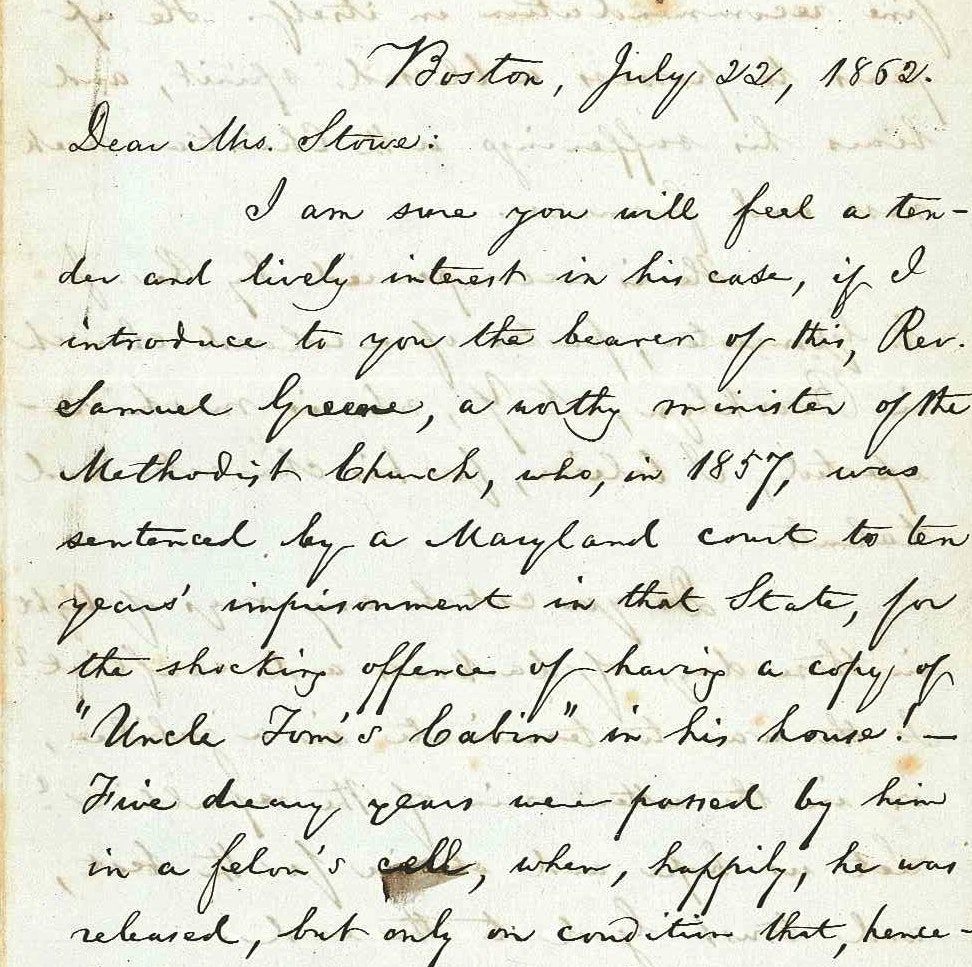

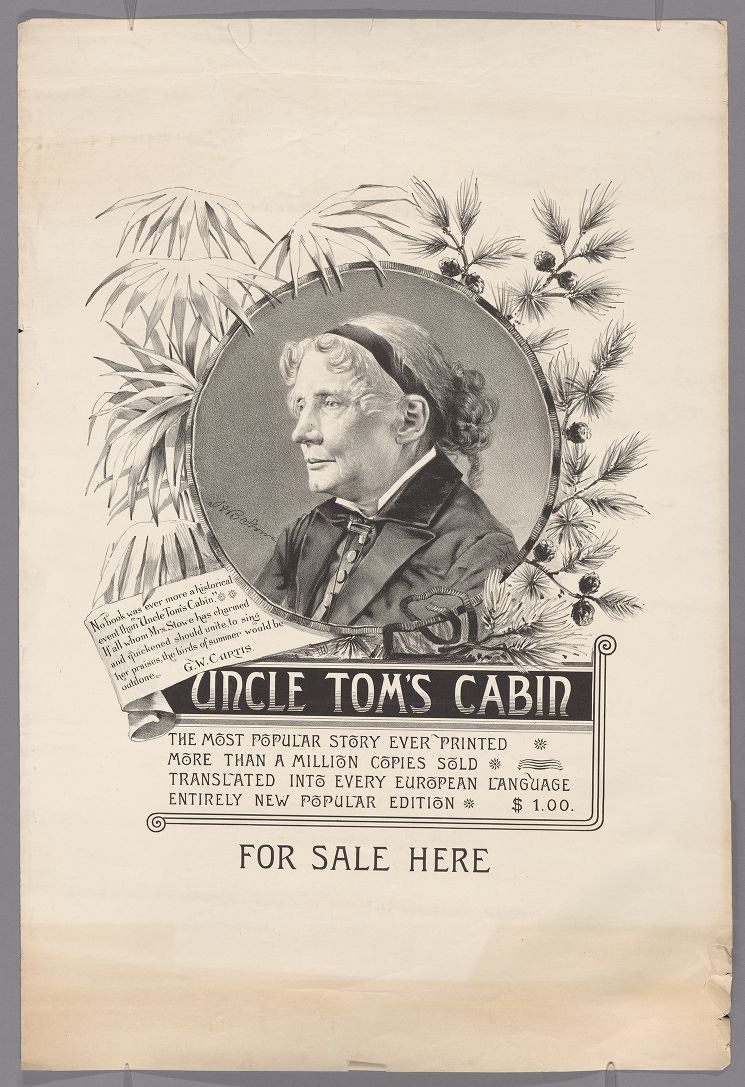

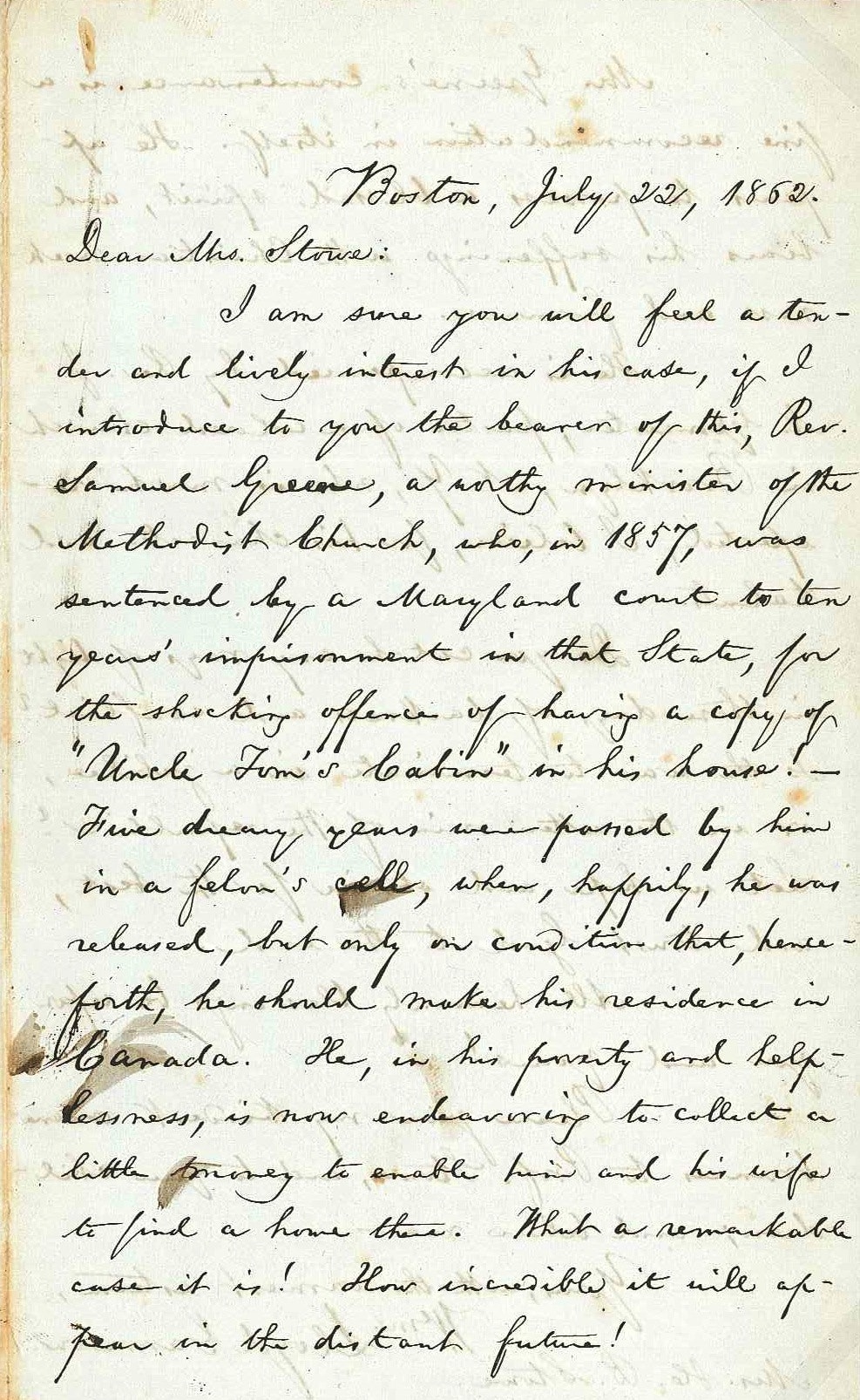

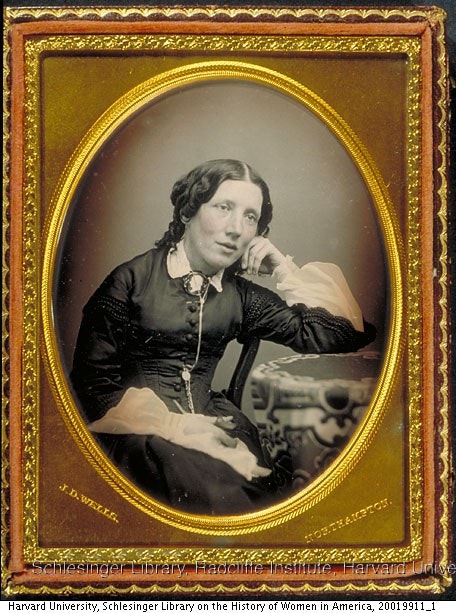

Harriet Beecher Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin

A Beecher family legend holds that President Lincoln greeted Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811–1896) at the White House in 1862 by declaring, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.”

This quote is not documented, but Stowe did meet Abraham and Mary Lincoln at the White House in 1862. Her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin and its adaptation as a play had become a sensation since its publication in 1852. Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought the plight of American slaves to a worldwide audience, ignited an intense public debate, added fuel to the abolition movement, and influenced public opinion leading up to the 1860 election.

Stowe was 40 when she wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin in response to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Born into a family of preachers, writers, and abolitionists, she had published numerous stories and sketches in popular and religious magazines, in part to morally instruct but also to supplement the family income.

Nothing, however, prepared her for the attention she received as a result of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. When asked about it, she sometimes said that she did not write the book, but that it came to her in visions and she simply wrote it down.

The Beecher Family and the Civil War

The Beechers were one of the most influential families of the time. Its members had written and preached about the immorality of slavery for decades and had taken action in various ways, including the purchase and freeing of slaves. When the war began, they supported it. Like other abolitionist families, they sent family members into the war as soldiers, officers, chaplains, and teachers: Harriet Beecher Stowe’s son, several nephews, two half-brothers, a brother-in-law, and a sister-in-law served in some capacity. Some Beechers survived the war intact, several were injured, and at least two suffered lasting psychological damage.

The Urge to Do One’s Part: Women and the War

The Civil War upended domestic life. Women on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line stepped up to take the place of absent men at home, while others left their firesides to support the war effort in traditional and nontraditional ways.

After the fall of Fort Sumter, thousands of women in the North began forming aid societies to supply soldiers with everything from underwear to medicine. In the fall of 1861, when Union forces took possession of South Carolina’s Sea Islands, the first of nearly 1,000 teachers—most of them women and New Englanders—headed South to teach newly freed former slaves.

During the first winter of the war, with casualties mounting, more and more women looked to nursing, still a new profession, as a way to serve.

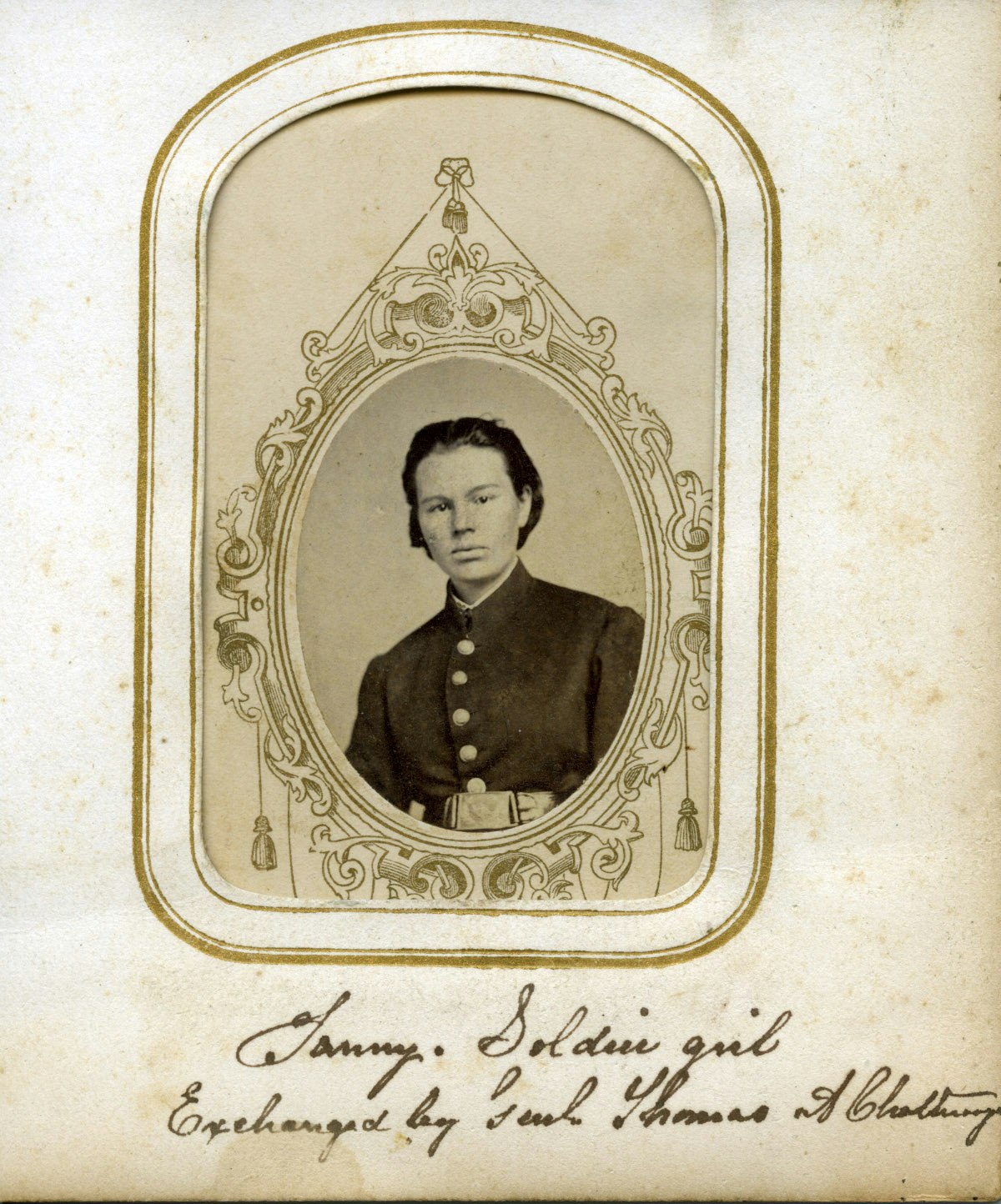

At least 250 (and likely many more) Southern and Northern women bound their breasts, cut their hair, and enlisted in the Union and Confederate Armies, where they bore arms, fought bravely, languished in prisons, and died miserably. Society matrons, servants, and farm wives engaged in espionage. Eavesdropping at parties, gathering information about troop size and fortifications, they sewed papers into their bodices and smuggled maps under their skirts.

The new responsibilities they undertook, the privations and heartbreak they endured, and the organizational talents they unleashed during the Civil War transformed women’s lives in ways that had long-term implications for all American women in the postwar years.

The War Front and the Home Front

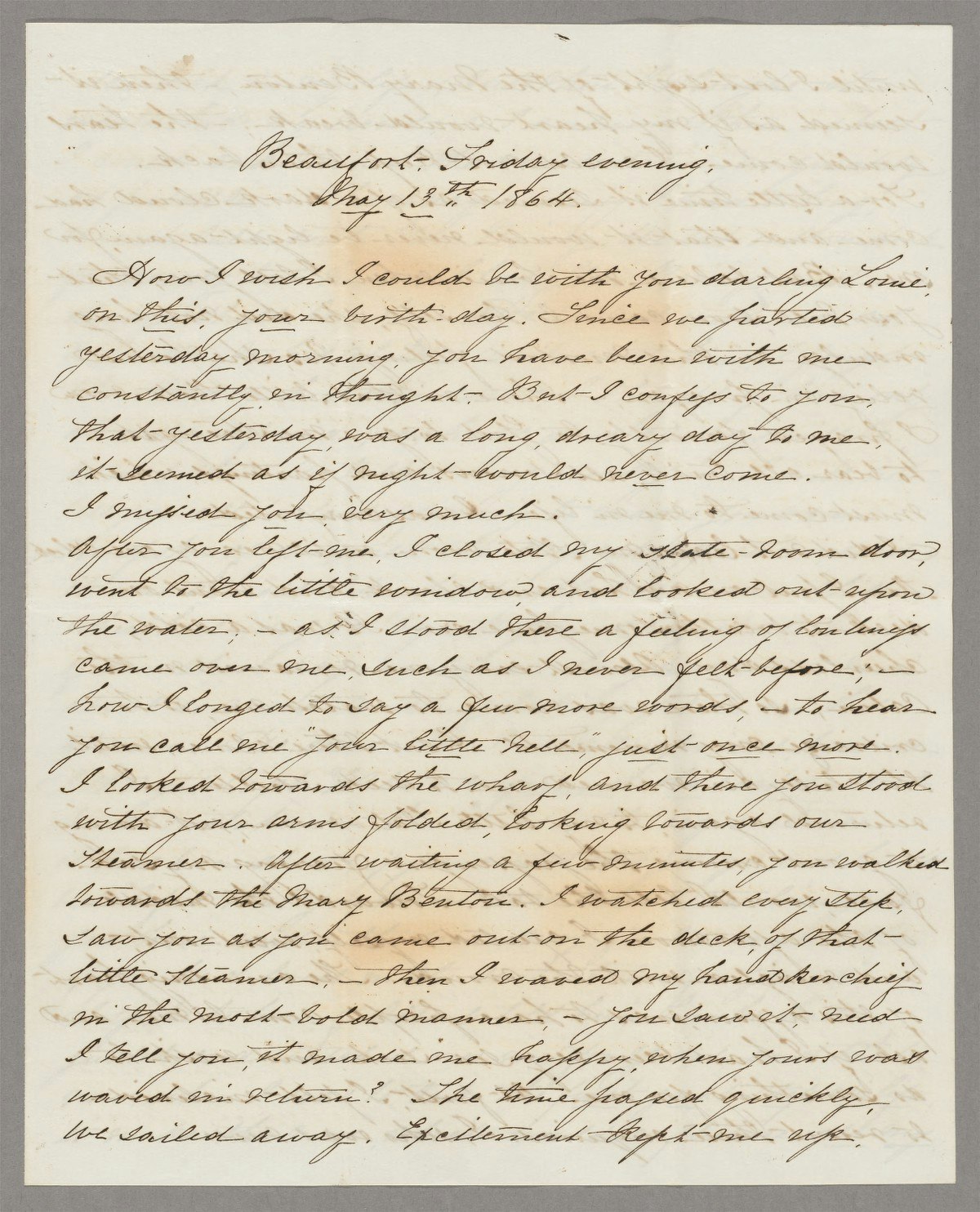

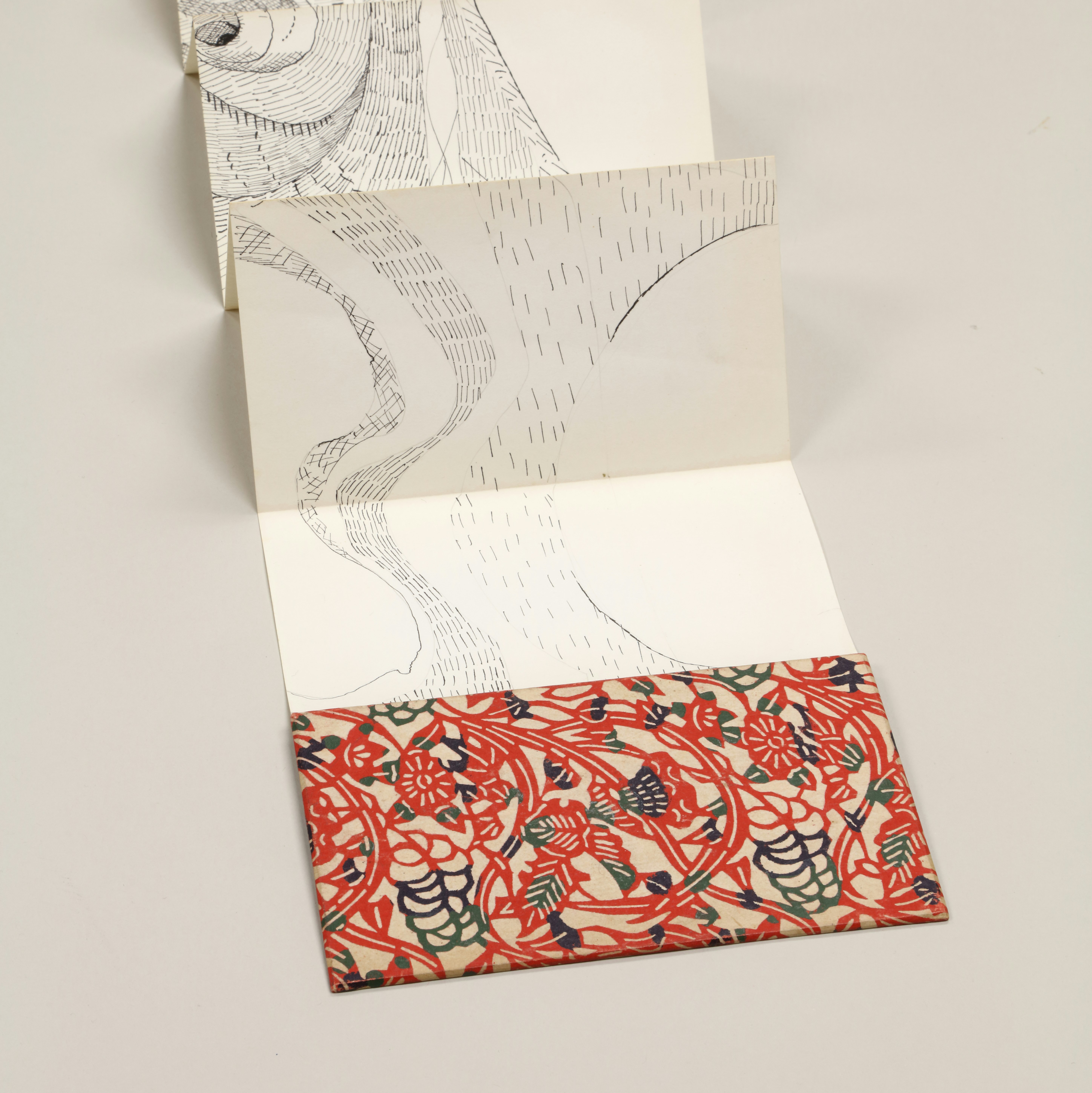

Diaries, drawings, courtship letters, a wooden comb, an etching. The objects contained in this case each represent a unique story in the daily lives of soldiers on the war front and those they left behind on the home front. Thanks to a relatively literate society, the Victorian penchant for personal writing, and the thoughtful preservation of the these objects by generations of family members, the library is able to feature first-person narratives as a pathway into the lives of individual soldiers and those close to them.

What these individuals chose to write about and save reveals their commonality and their individualism. Each dealt with the realities of the Civil War in his or her own way. Aside from the battlefield strategies and politics of the war, correspondence about the daily struggles and the mundane details of soldier life are a window into the more personal side of the war. These stories are relatable even today, some 150 years later. Those at home shared news and discussed debts that had to be paid, house chores that had to be done, and fields that must be plowed—all the minutia of life that continues, even in wartime.

Duty, Love, and Loss: The Browne Family of Salem, Massachusetts

In 1863 Albert Gallatin Browne Sr., an ardent abolitionist who hoped to better his family financially, took a position in Beaufort, South Carolina, as a special agent of the United States Treasury appraising contraband, such as cotton, that fell into Union hands. Browne longed for his family and, alone in unfamiliar surroundings, found himself in need of domestic assistance:

I cannot live in a “Mess” and maintain the dignity which is absolutely necessary from the nature my position.

—Albert Gallatin Browne Sr., November 2, 1863

He immediately sent for his daughters, Sarah Ellen (“Nellie”) and Alice, and although initially reluctant to leave Salem, his entire family joined him in April 1864. Within just a few weeks, Nellie became engaged to Lewis Ledyard Weld, then a captain in the 7th US Colored Troops, and nephew of the abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld. Tragically, Nellie died of typhoid fever in June 1864, and her “beloved Louie” died from a “severe cold” seven months later near Petersburg, Virginia.

Their courtship correspondence, saved by Lewis Weld and returned to Nellie’s family upon his death, speaks of the transformative nature of love and duty to country:

I am singing a song in my heart every hour in the day. I wonder at myself, at the change you have made in me. I am a better man—a prouder happier stronger man because of my love for you—I have at last a new object in living.

—Lewis L. Weld, May 13, 1864

Dear Louie, do not think I do wrong when I tell you, that each day I pray God to spare your life to me. Yet if duty called you into battle, I feel that with my Heavenly Father’s help, I could bless you, and urge you on. It would be a hard trial for me, but the love I bear to you is so deep, that for your sake, I would try to act as a true woman should, at such a time. This love for you will make a great change in me. I feel that I shall be a better, truer, woman because of your love.

—Nellie Browne, May 21, 1864

After the war, Albert Gallatin Browne Sr. returned to Salem suffering the ill effects of malaria. Having received only partial payment for his services as treasury agent, he filed an unsuccessful claim against the government and was left financially and physically depleted by his wartime service.

The Fox Family: Ministering to the Dying and Laying the Dead to Rest

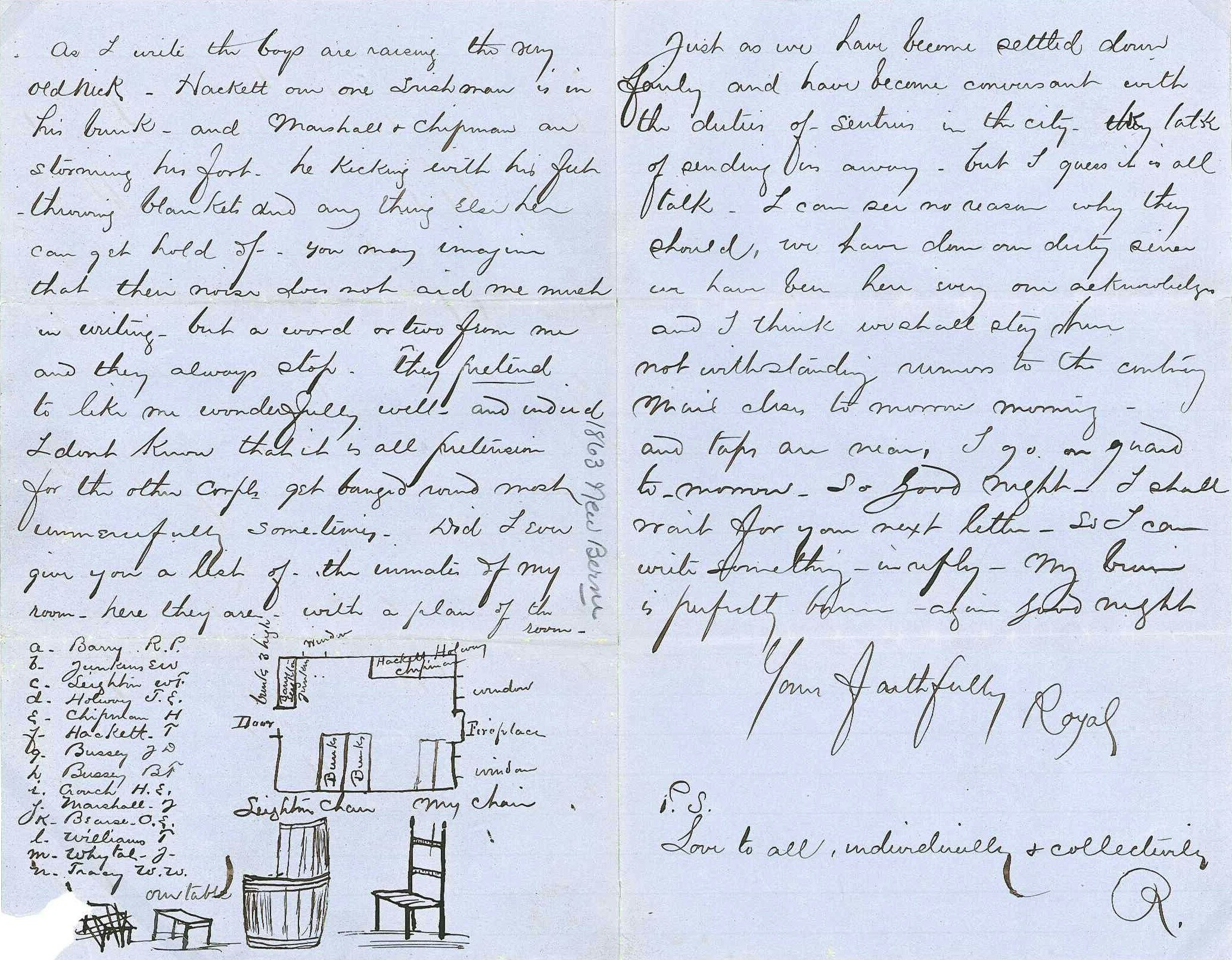

Through the Fox family’s letters, it becomes clear how devastating the death of a soldier in the war could be and how little the families back home knew of army life. The Fox family letters are also full of humor and the dullness of daily camp life. They open a window onto the general interactions among family members during the Civil War and how they understood and communicated joy, loss, tragedy, and triumph.

Thomas Fox Jr. was injured in the Battle of Gettysburg. He was immediately transported home to Dorchester, Massachusetts, where he died shortly after, surrounded by his parents, youngest sister, and a family servant. In addition to the outpouring of grief and support for the family found in letters in the collection, other letters make clear that the fiscal accounts of the deceased needed to be addressed—a long and convoluted process that was laid at the feet of Tom’s brother John.

The Fox Family and the Civil War

The Civil War was a tumultuous time, not only on a national level, but also on the family level. The Fox family is a subset of the prominent Poor family of New England, whose papers span two centuries. By focusing on the Fox family and the ways in which their relationships grew and how they communicated, we shed light on three major groups of people during the war: those who enlisted, those who maintained the home, and those who helped the war effort in ways other than military service.

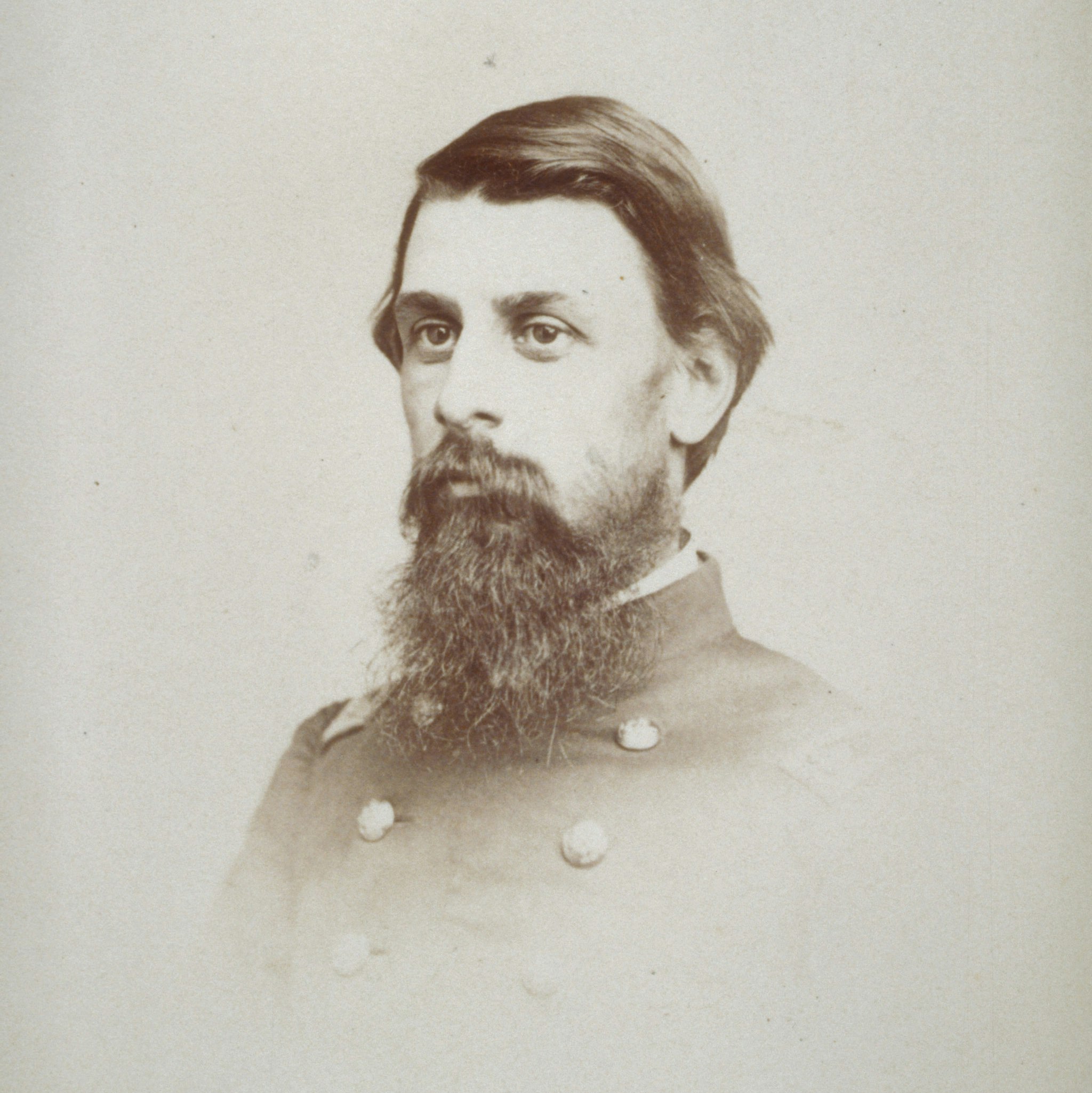

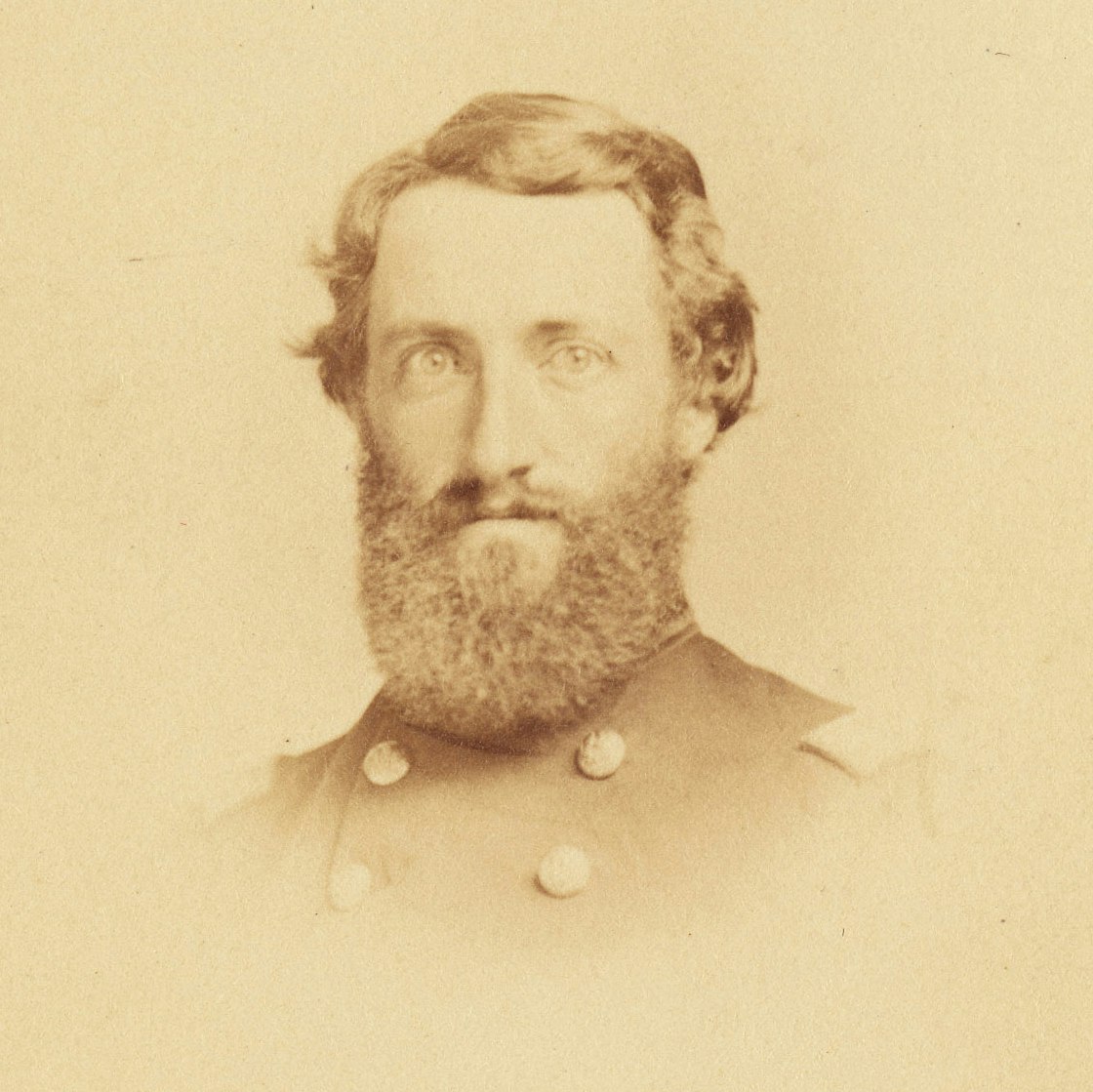

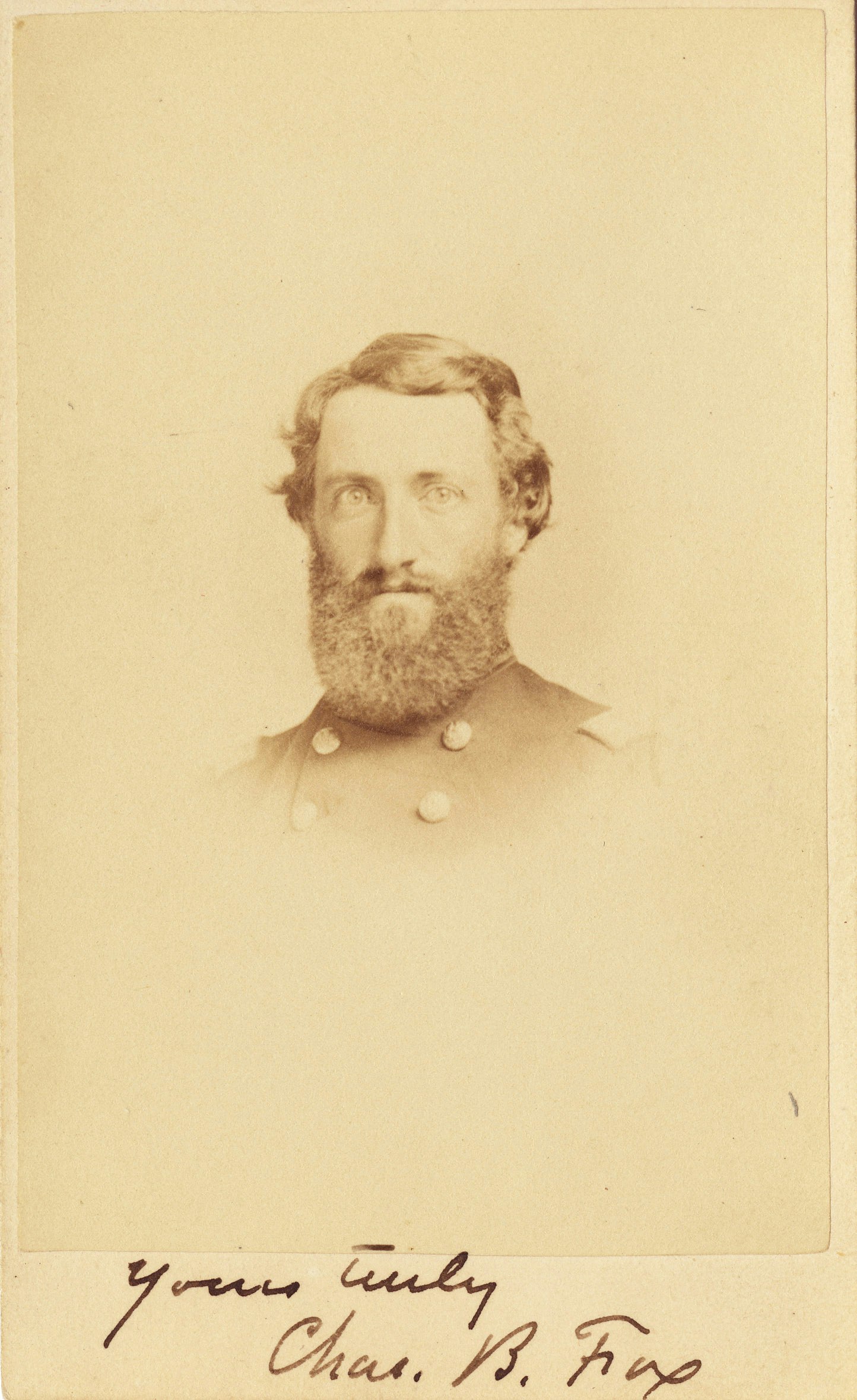

Thomas B. Fox Sr. and his wife, Feroline Walley Pierce Fox, had five children. Three—Charles A., Thomas B. Jr., and John A.—enlisted in the US Army. Charles was a major in the 55th Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry, and Thomas Jr. and John served with the 2nd Regiment, Massachusetts Infantry. Thomas Sr. was an ordained minister who worked with the US Sanitary Commission and served the surgeon general of Massachusetts by ministering to sick and wounded soldiers within the camps. These letters explore the lighthearted exchange between older brother and younger sister, the informative nature of communication between father and enlisted sons, the tender correspondence between lovers, and the banter between friends.

Two Women, Two Worlds

Ann Maria Davison, born in 1783, spent almost her whole life in New Orleans and on a nearby plantation surrounded by the slaves owned by her son-in-law, a prominent attorney and civic leader. The six volumes of her diary span the years from 1847 to 1860 and reveal how this educated, articulate, and devoutly religious woman carefully studied scripture and formulated her unequivocal criticism of slavery and the culture that depended on it. Even more radical, her religious convictions led her to argue for the equality of the races. She saw slaves as individuals, wrote down their names, told their stories, and detailed her own efforts to ameliorate their conditions. As she read and traveled widely, Davison’s focus sharpened. She refuted proslavery arguments, collected eyewitness accounts of slavery’s horrors, and traced a growing intransigence among slaveholders in her own family and in her social circle.

Ann Reeves grew up in New Castle, Delaware. In October 1861, when her one-volume diary began, she was a widow of means perhaps in her mid-40s, well-read, living in Delaware but about to take her leave. With her four children, seemingly all young adults, she was determined to leave “Yankee land” for the Confederacy. By December they had reached their destination, a plantation called Rossmere in Chicot County, Arkansas. While she gave no explanation for her devotion to the South, there is no mistaking Reeves’s ardor for the chivalrous plantation culture that she regarded as the apogee of civilization. She wrote of belles, beaus, and weekend visits eventually curtailed by raids carried out by despised Northern “invaders.” Reeves paid little attention to the slaves around her—180 of them at Rossmere when she arrived. She took them for granted, lumping them together with animals and property (“this raid was to take off horses, Beeves [cows] and negroes”).

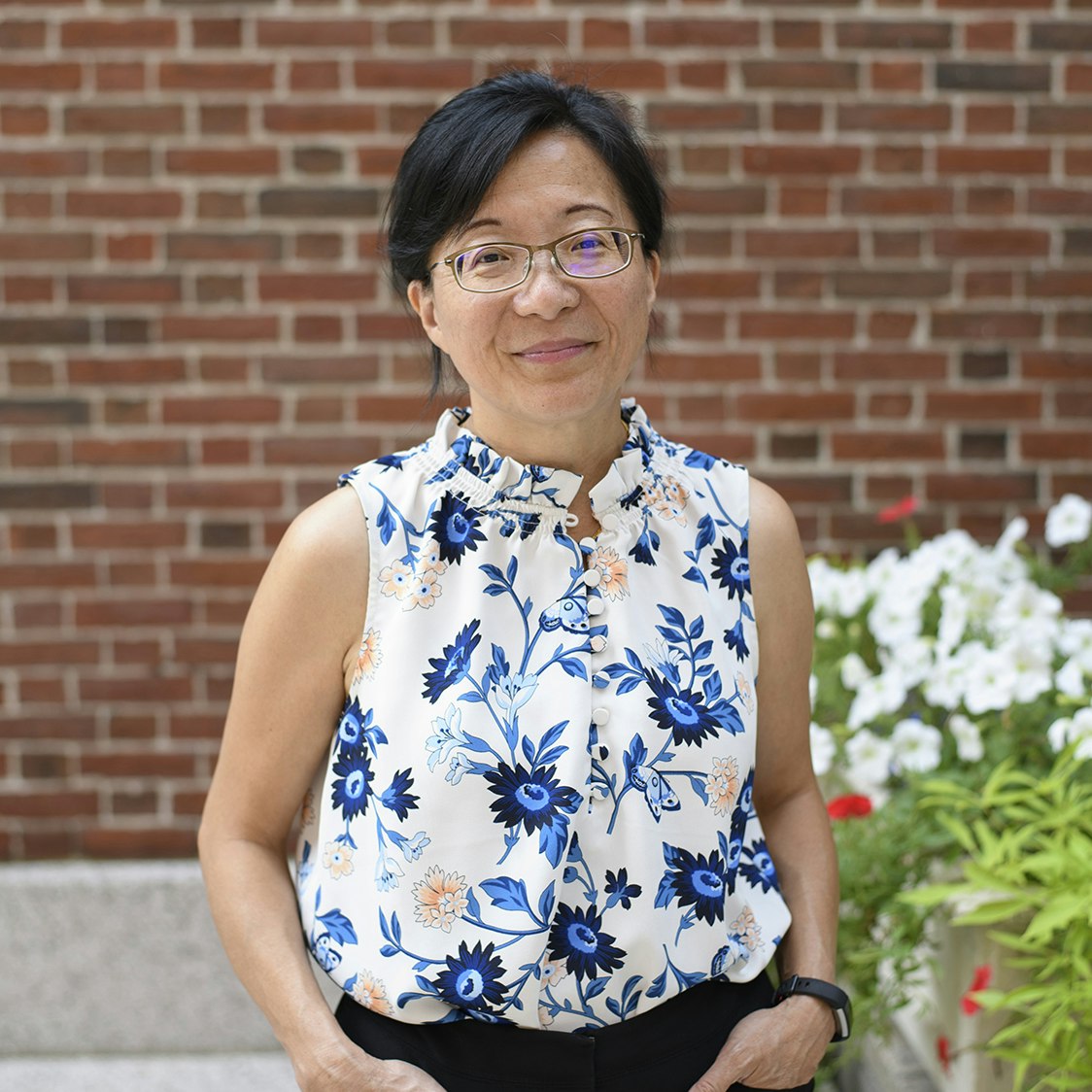

Daguerreotypes

Daguerreotypes were one of the earliest forms of photography. Internationally popular through the 1850s, they still held an allure for the American public through the early 1860s. While the Civil War saw the rise of other forms, namely the tintype and carte de visite, the daguerreotype was valued for its uniqueness and intimacy. Often in cases lined with velvet, as can be seen here, the images have an immediate and precious quality. Two of the portraits date from before the war, during the heyday of the medium. The stunning portrait of Harriet Beecher Stowe was taken shortly after the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe may be wearing the black silk dress she had longed to purchase and was now able to, with the proceeds from book sales. The postmortem portrait of Stowe’s sixth child, Samuel Charles Stowe, was taken after he died of cholera at 18 months, while the family was living in Cleveland. Postmortem portraits, particularly of young children, were common at the time and often the only likeness made of the child. In this portrait, little Charley is shown holding a sprig of flowers and appears to be sleeping peacefully. The third daguerreotype is of Charles Barnard Fox in his military uniform, taken as a remembrance for his family at home in Massachusetts.