Until Safety is Guaranteed: Women and the Fight Against Violence

In 1993 the United Nations defined violence against women as any "act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life."

This exhibition provides historical evidence on the topic of gender violence and documents the experiences of women who have survived domestic abuse and sexual violence. It also documents grassroots activism around issues such as the connection between pornography and violence, victim assistance, and self-defense training. Also displayed are materials that show success in the fight against violence, including efforts to educate the public and to protect women through the legal and legislative achievements of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

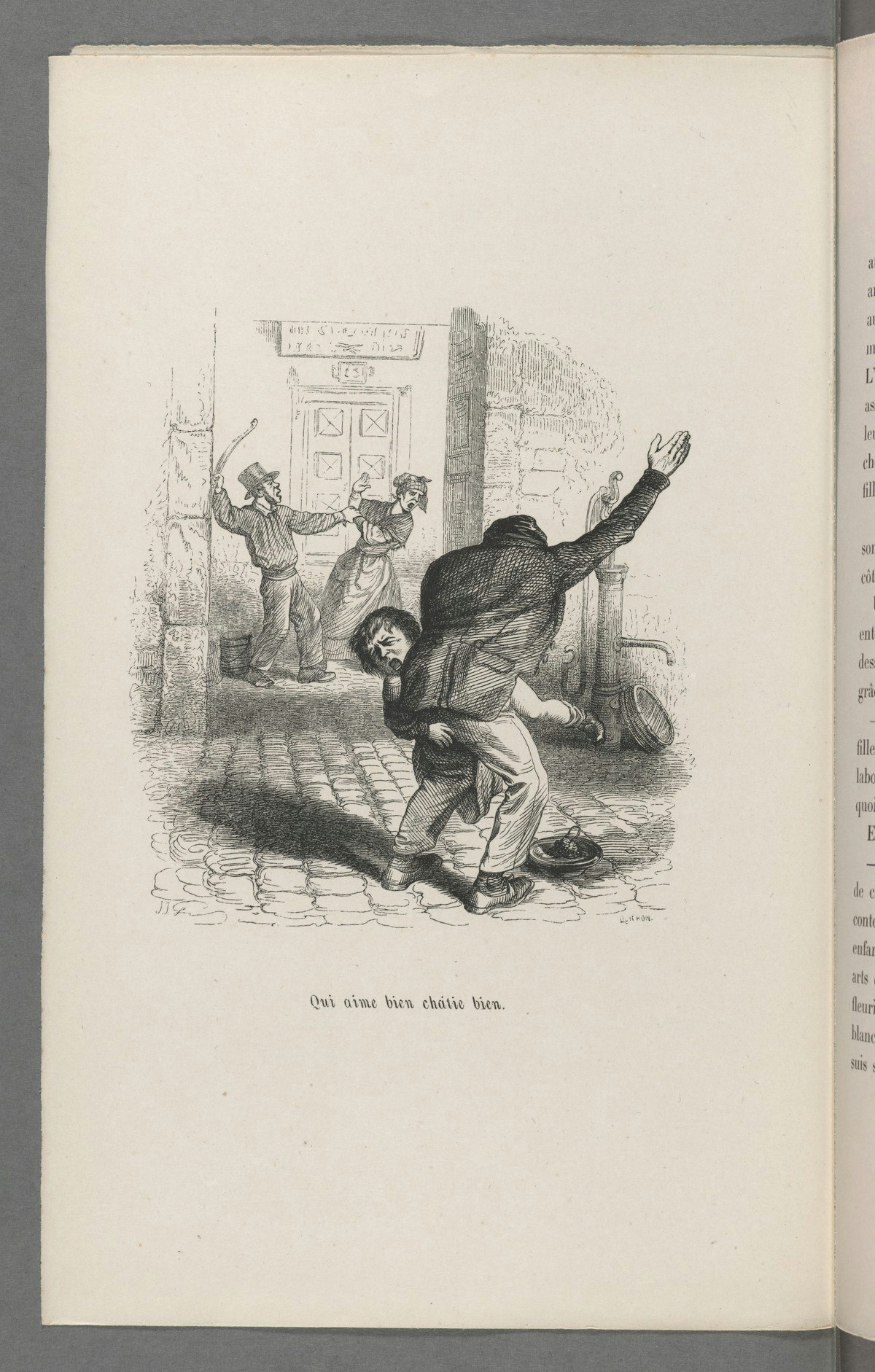

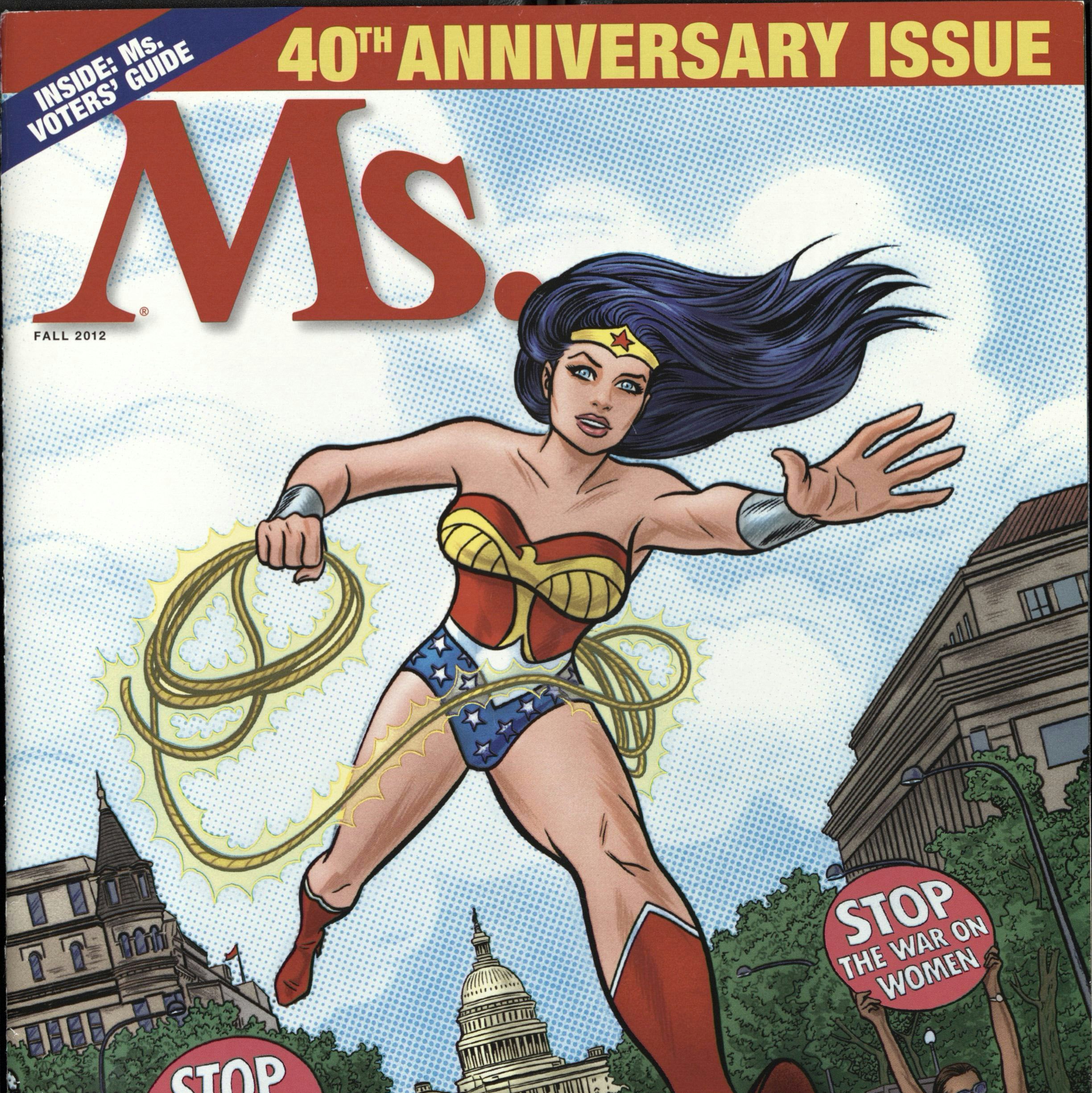

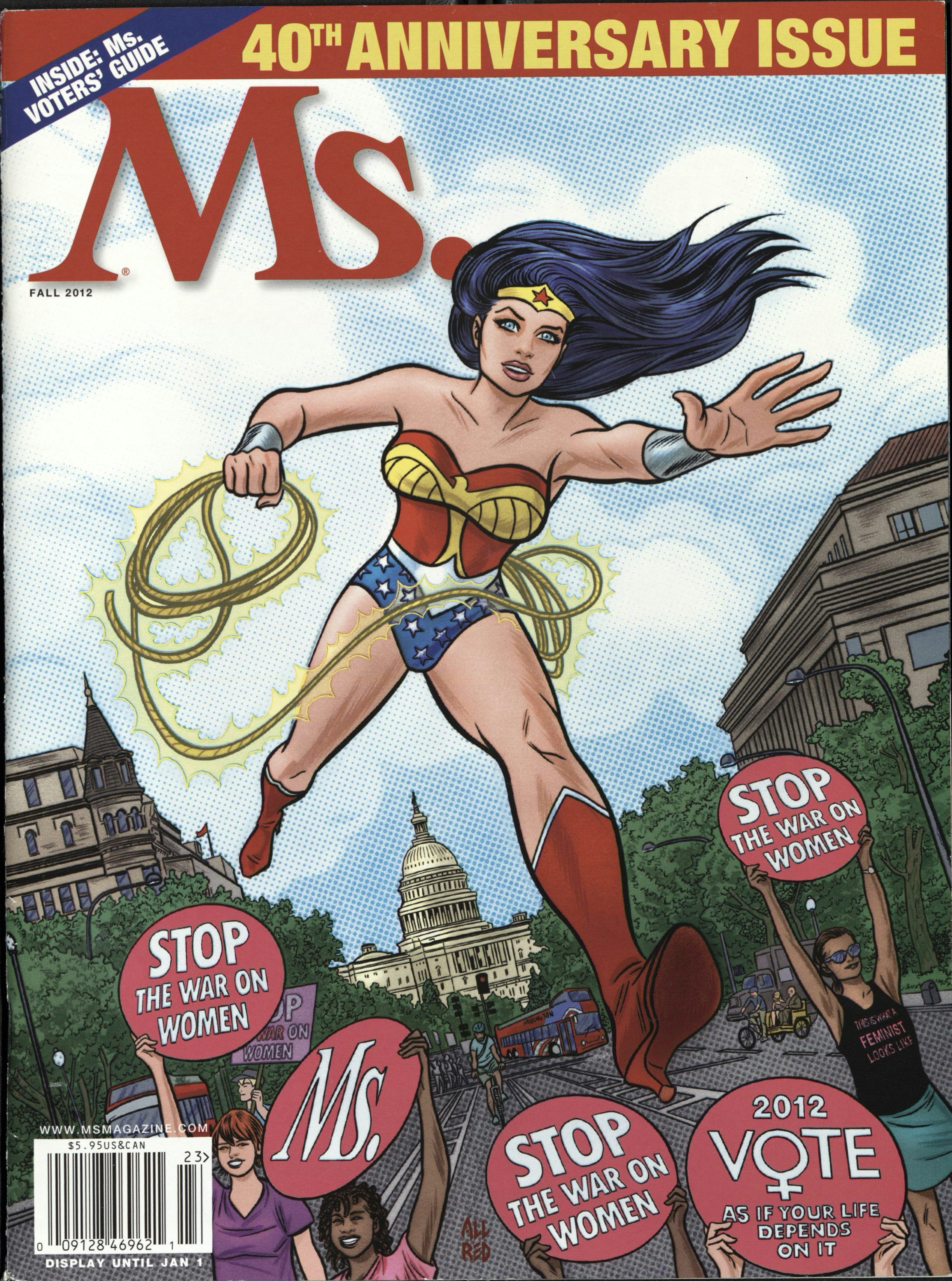

Violence against women has been tolerated because many cultures have viewed—and some continue to view—women as subservient or as property. It has been sanctioned by those in power or deemed legal in egregious practices such as wife "correction," rape in time of war, honor killings, and in the burning of witches. It has gone on in the privacy of the home and in public spaces. The feminist movement of the late 20th century brought attention and redress to this issue, but much remains to be done.

In Print

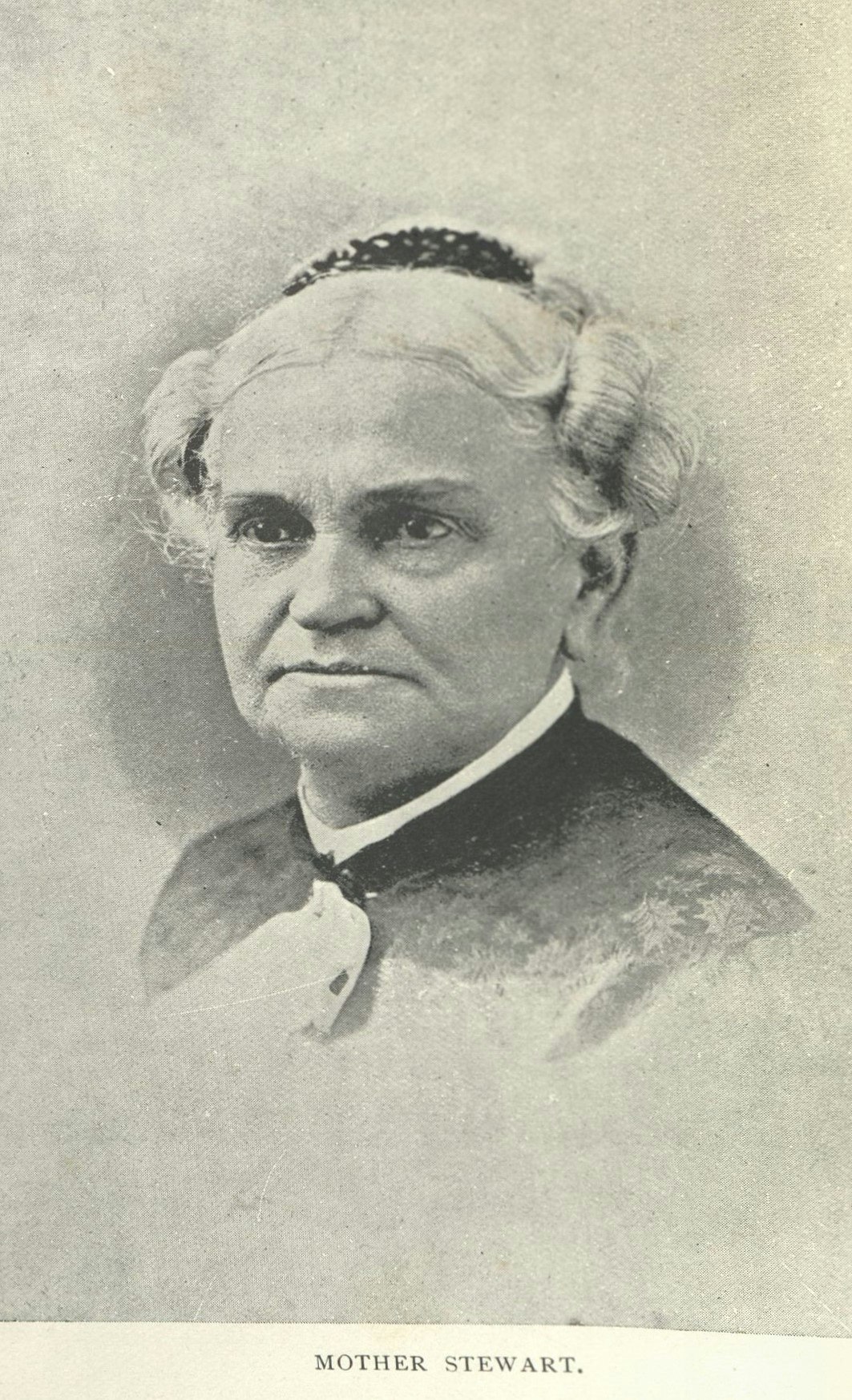

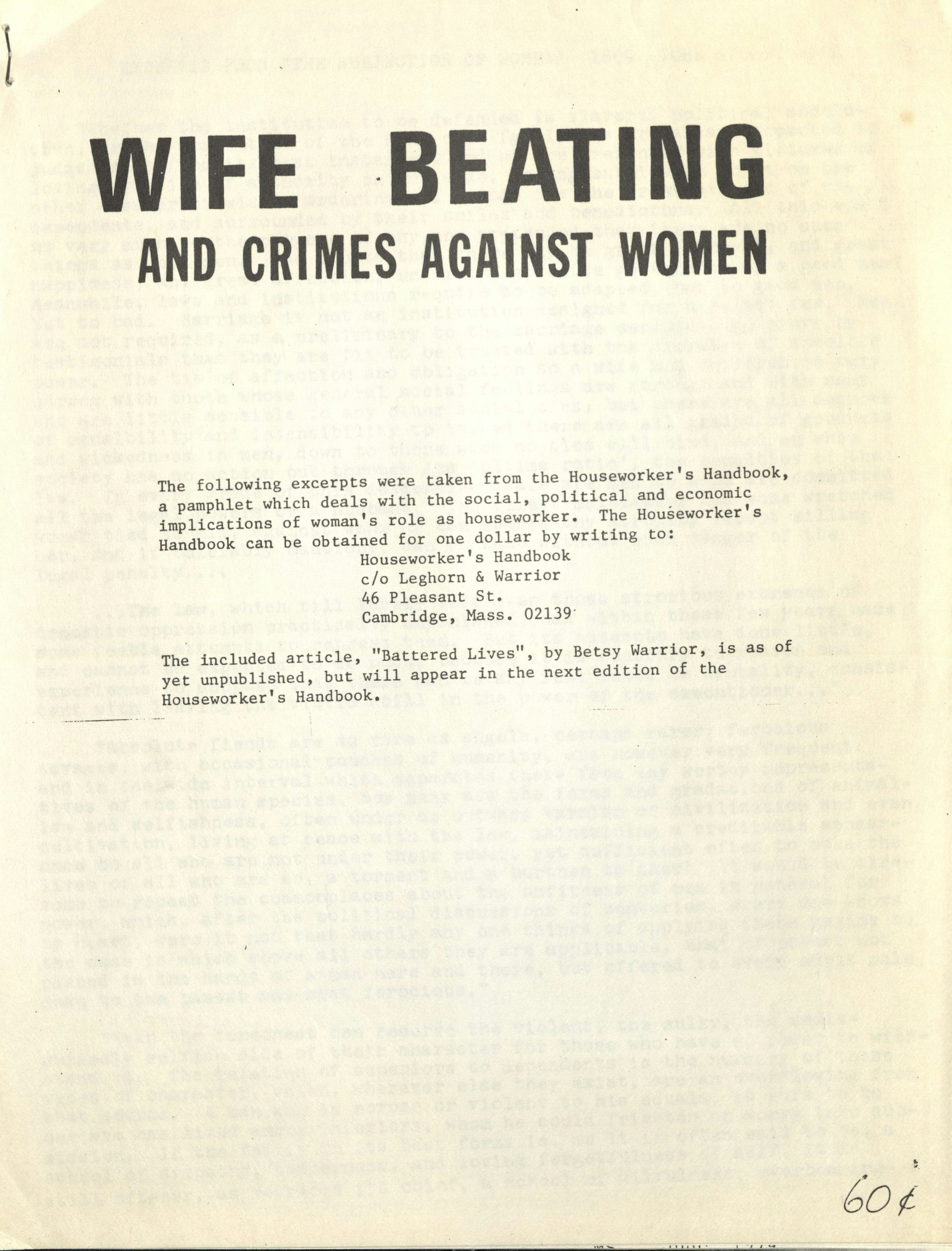

Various messages regarding violence against women are evident in printed material from the 19th and 20th centuries. References to the physical and emotional abuse of women can be found in etiquette guides, fiction, and even advertising. While in some advice and etiquette manuals the acceptance and necessity of “punishing” one’s wife is clearly condoned, in others men are advised against mistreatment of their wives. The very existence of this advice to men indicates that the practice was common. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union protested physical and sexual violence in the home, linking such violence to “drunkard husbands.” In the 20th century, advertising directed at both men and women includes disturbing images of physical and sexual violence against women, suggesting approval to men and acceptance by women. While some attempts at protest were made in earlier periods—particularly by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union—battering, spousal rape, and other violence would not be subjects of public discourse again until the mid-20th century.

Personal Stories of Violence and Survival

Women of all ages have experienced abuse for centuries, ranging from psychological to physical violence and including but not limited to sexual assault. Perpetrators may be male or female, strangers, friends, or family members, and abuse occurs in the supposed safety of home or out in the world. Too often stories of abuse are kept hidden or secret. Increasingly, however, women are speaking out or writing about the abuse they have suffered, sometimes finding the act of sharing their stories empowering and freeing. Women who have experienced and fought against abuse and sexual violence have shared their personal stories in venues ranging from support groups to “Take Back the Night” marches. Often the act of sharing these experiences has been transformative, encouraging women to aid other survivors of violence actively through support and counseling at shelters and in women’s centers. In some cases, no resolution seems possible except to react to men’s assaults with further violence, thus raising the disturbing reality of violence begetting violence.

The Emergence of Activism

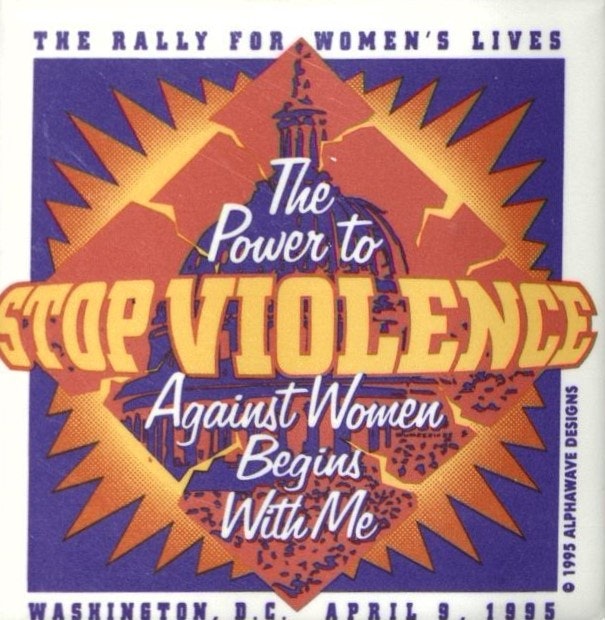

Second-wave feminism in the early 1960s broadened the discussion of gender inequality to include topics of sexuality, reproductive rights, the workplace, and legal disparities. It also began to draw attention to violence against women. This attention prompted the formation of a grassroots movement in which women, mostly volunteers, began to form communities to address the needs of survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault. They donated their time, energy, and expertise, gathering information and marshaling resources in order to bring greater awareness of the issues and to create safe spaces for survivors. Grassroots organizations provided services in the form of temporary shelters, support hotlines, short-term counseling, workshops, and legal representation. Women organized protest marches, vigils, and other safe spaces for healing. Activists also conducted research on domestic violence, rape, and other forms of sexual assault, generating literature and statistics regarding the frequency of these crimes and the difficulties women faced when seeking assistance. Organizations also built intentional coalitions with men who supported ending violence against women and often offered counseling for men interested in addressing and changing their past actions. Although these organizations were under constant threat of losing their funding, the need for their services continues to be apparent as violence against women has persisted.

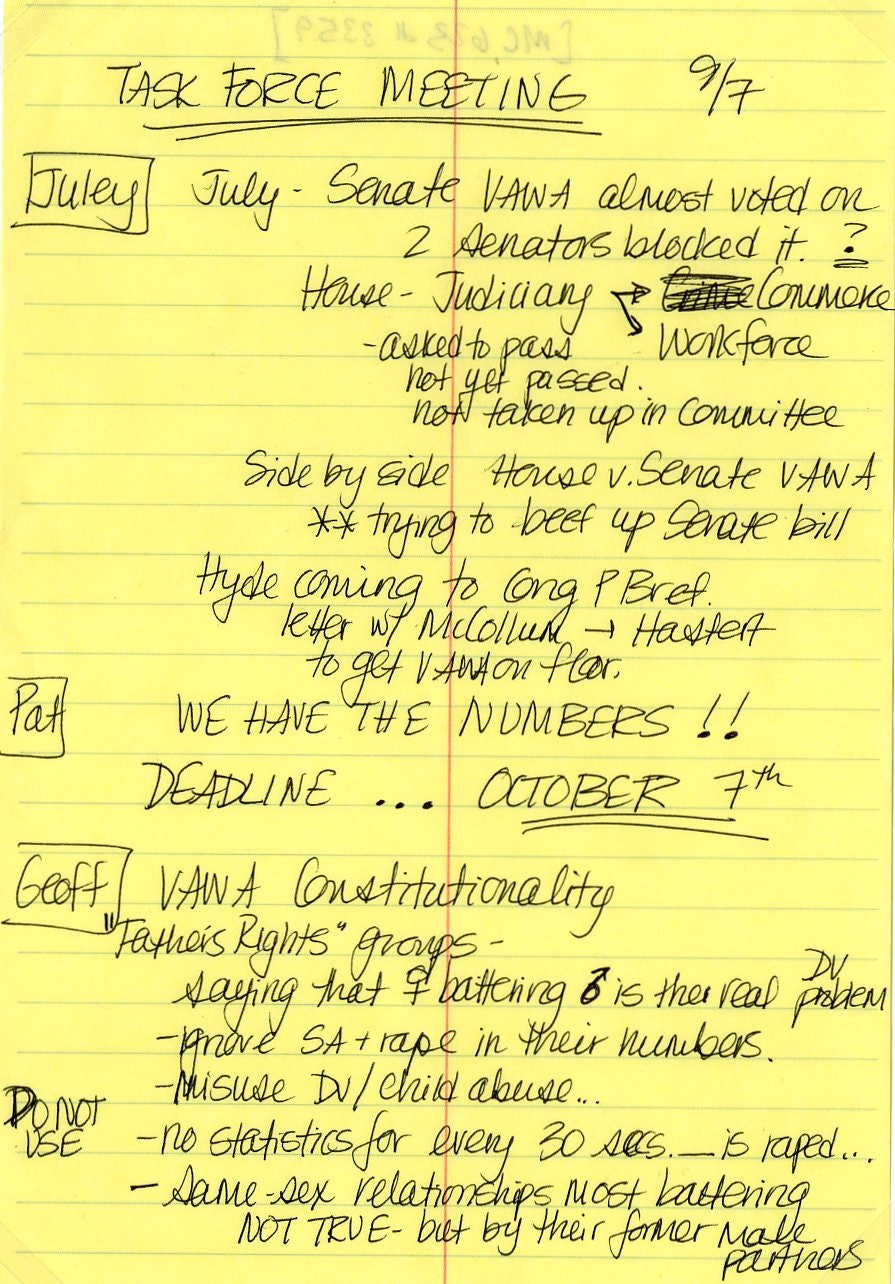

Gender-Based Violence and the Law

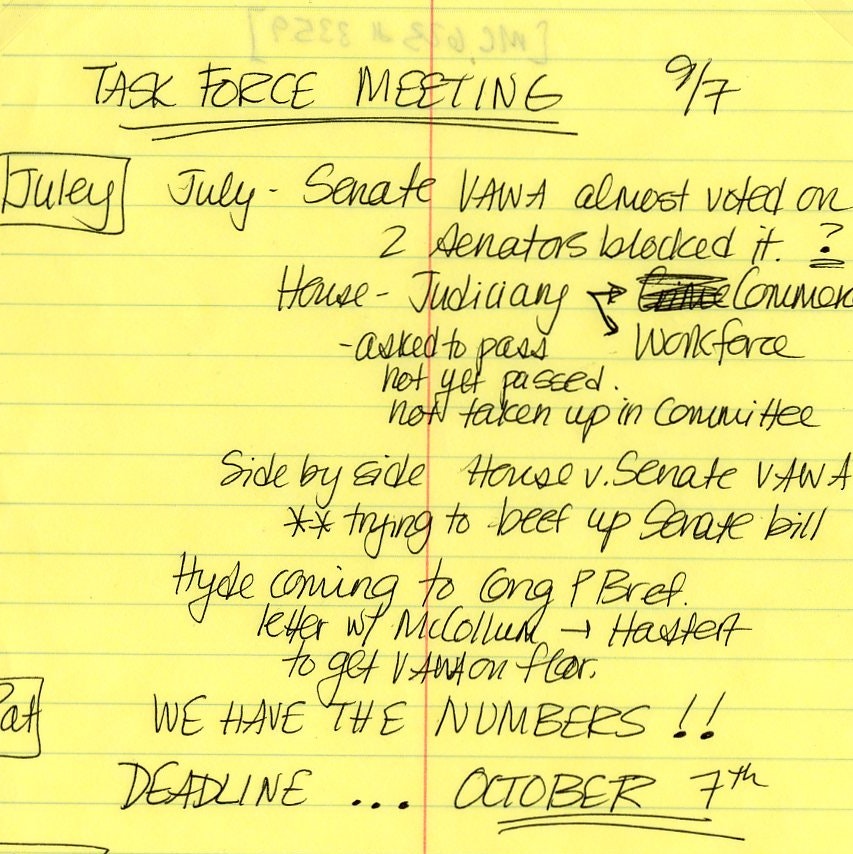

As grassroots organizations protested violence against women and offered services to battered women and rape survivors, they also began working with police to improve the treatment of victims by the police and the legal system writ large. Following their lead, larger organizations such as the NOW Legal Defense and Education Fund (currently Legal Momentum) began to advocate for systemic change. They lobbied for legislative action that would protect women from the all-too-common violence they were subjected to in American society. In addition, they provided training for judges through their National Judicial Education Program, offering instruction in the special conditions of survivors of domestic violence and rape. The continued work of these organizations resulted in passage of the Violence Against Women Act in 1994, its subsequent reauthorization in 2000, and another hard-won reauthorization in 2014. Legal Momentum’s success is described on their website, which states that their “targeted litigation, education, policy advocacy, and research help to shape the laws and policies that affect gender equality and ensure that they are properly implemented and enforced.”

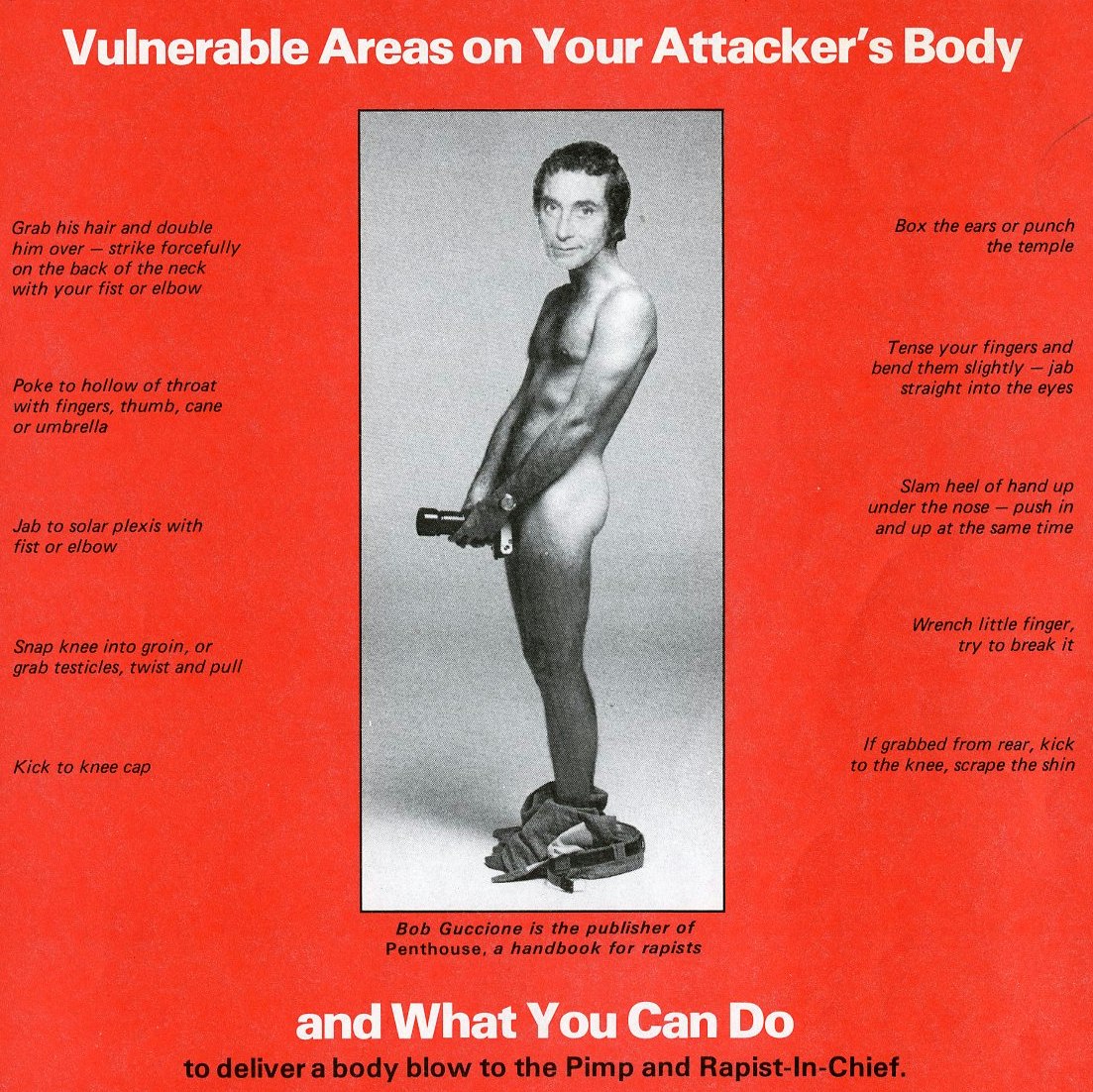

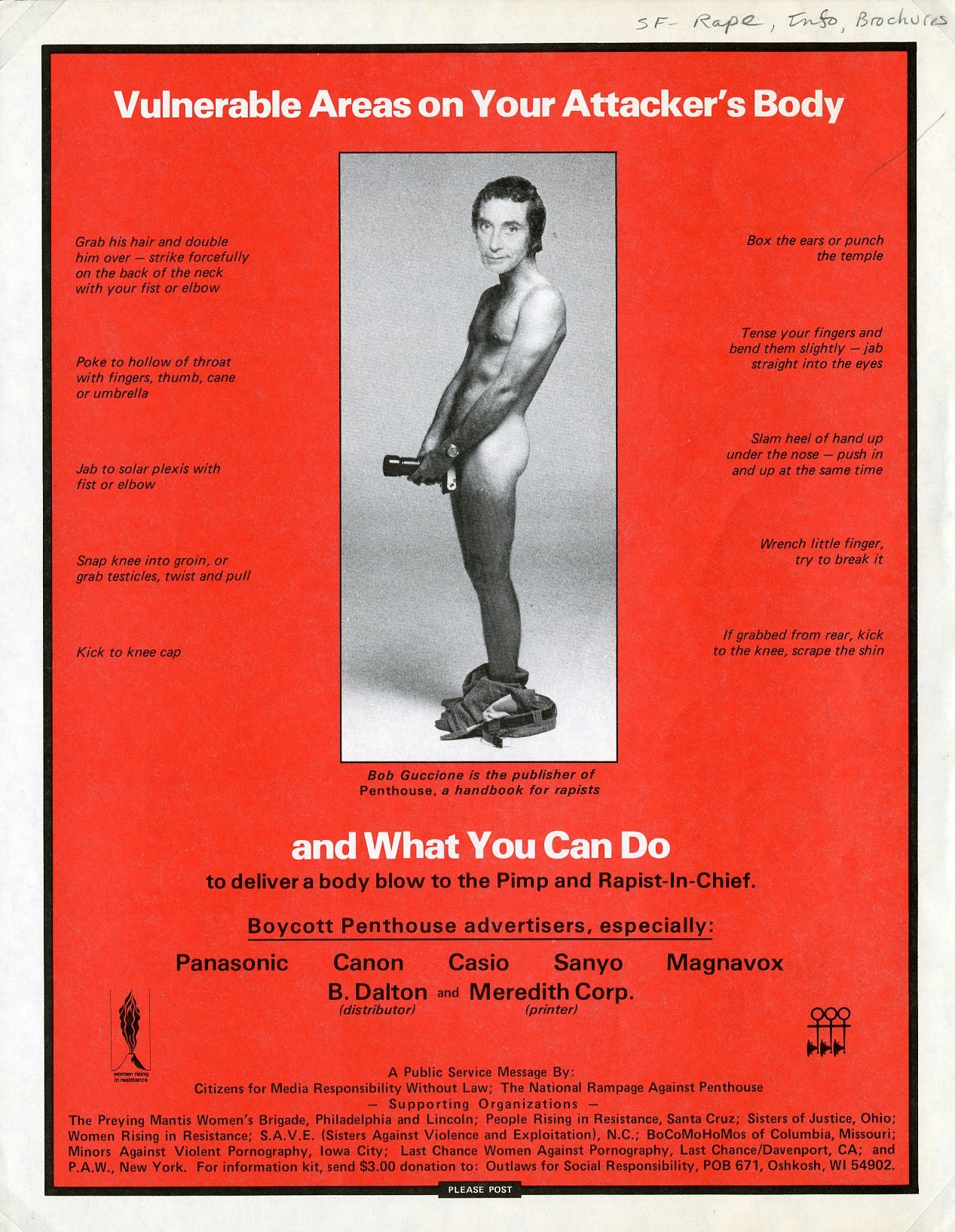

Women's Self-Defense

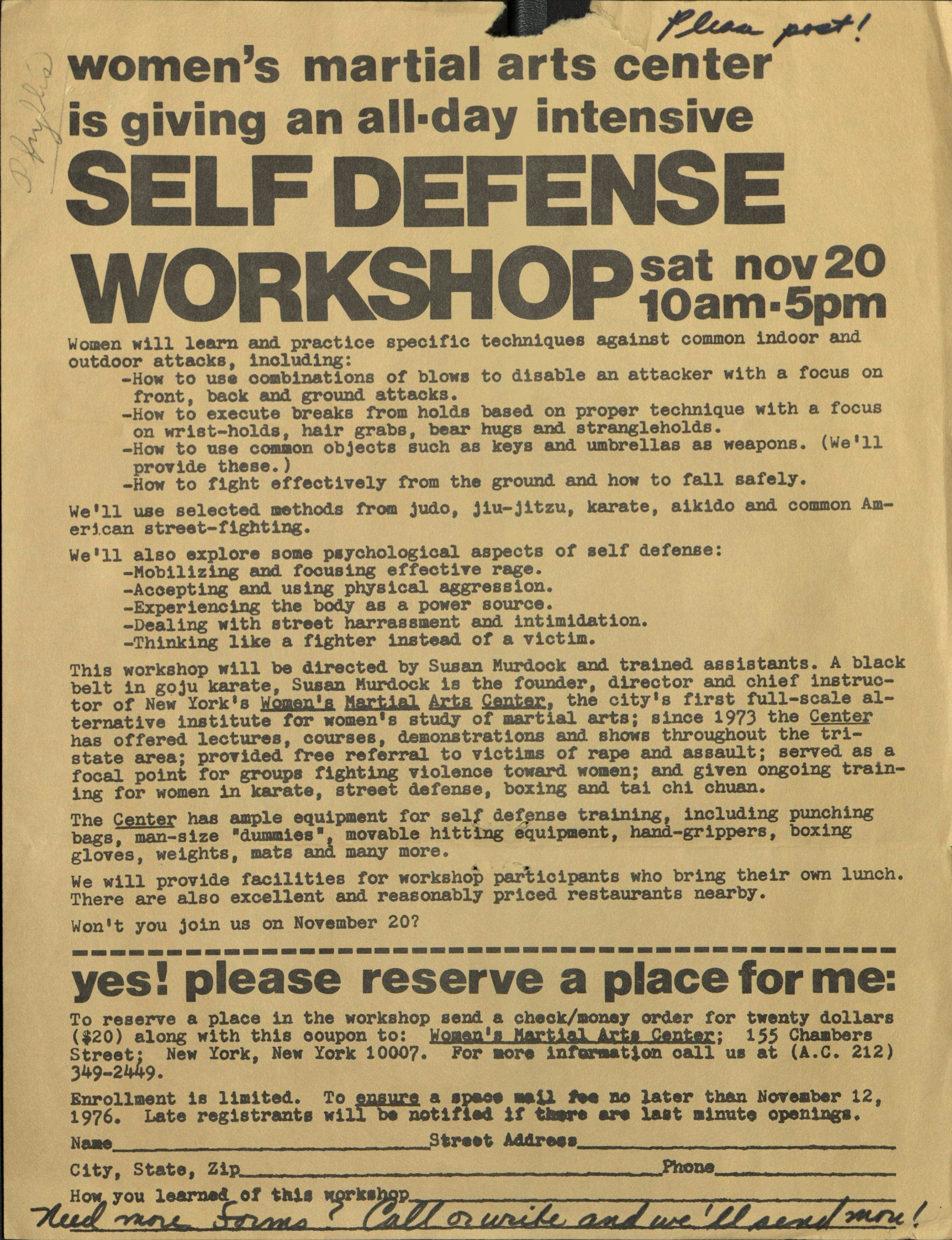

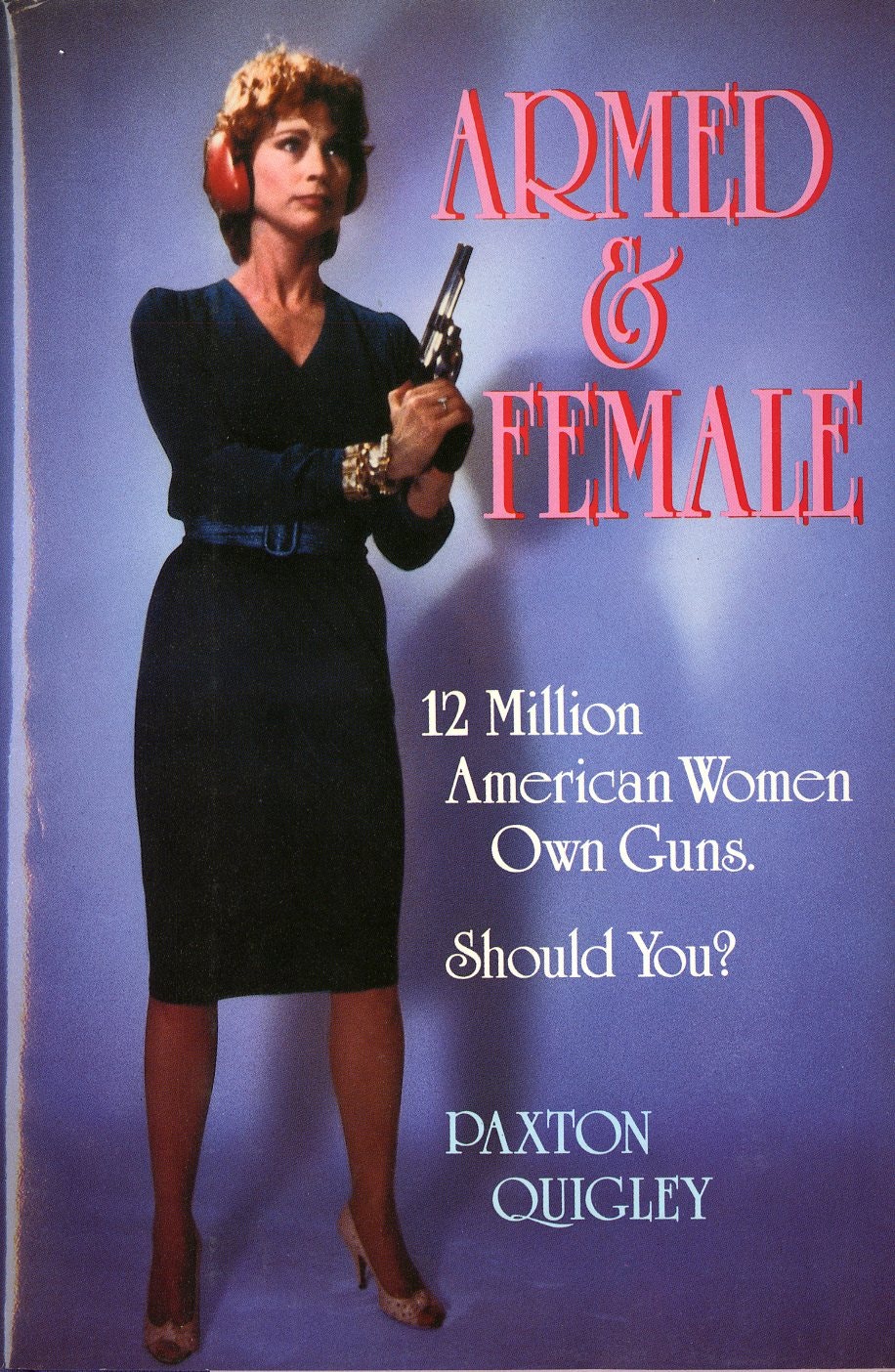

There are many recognized strategies for self-defense, including situational awareness to avoid dangerous places or situations, yelling and other verbal and psychological tactics to stop an encounter from escalating, physical defense that focuses on vulnerable spots to take down an attacker in order to escape, and the use of weapons to disable or kill an attacker. In self-defense, the women’s movement condoned and even urged violence against men.

Early books and pamphlets on women’s self-defense focused on the avoidance of violence by limiting nighttime activities, traveling with a companion, and altering public behavior and dress to avoid drawing attention to oneself. By the 1970s and 1980s, women encouraged one another to fight back and defend themselves physically. A large number of self-defense manuals for women were published, and activists organized classes and workshops on college campuses and in martial arts studios as the problem of violence became more publicly visible. Although some introductory text in manuals seems to perpetuate the view of women as victims and men as attackers, self-defense tactics from a feminist perspective encouraged women to have confidence in themselves and a willingness to fight for their lives when necessary. R.A.D. Systems rape aggression defense programs are currently offered by local and university police departments nationwide.

Pornography as Violence

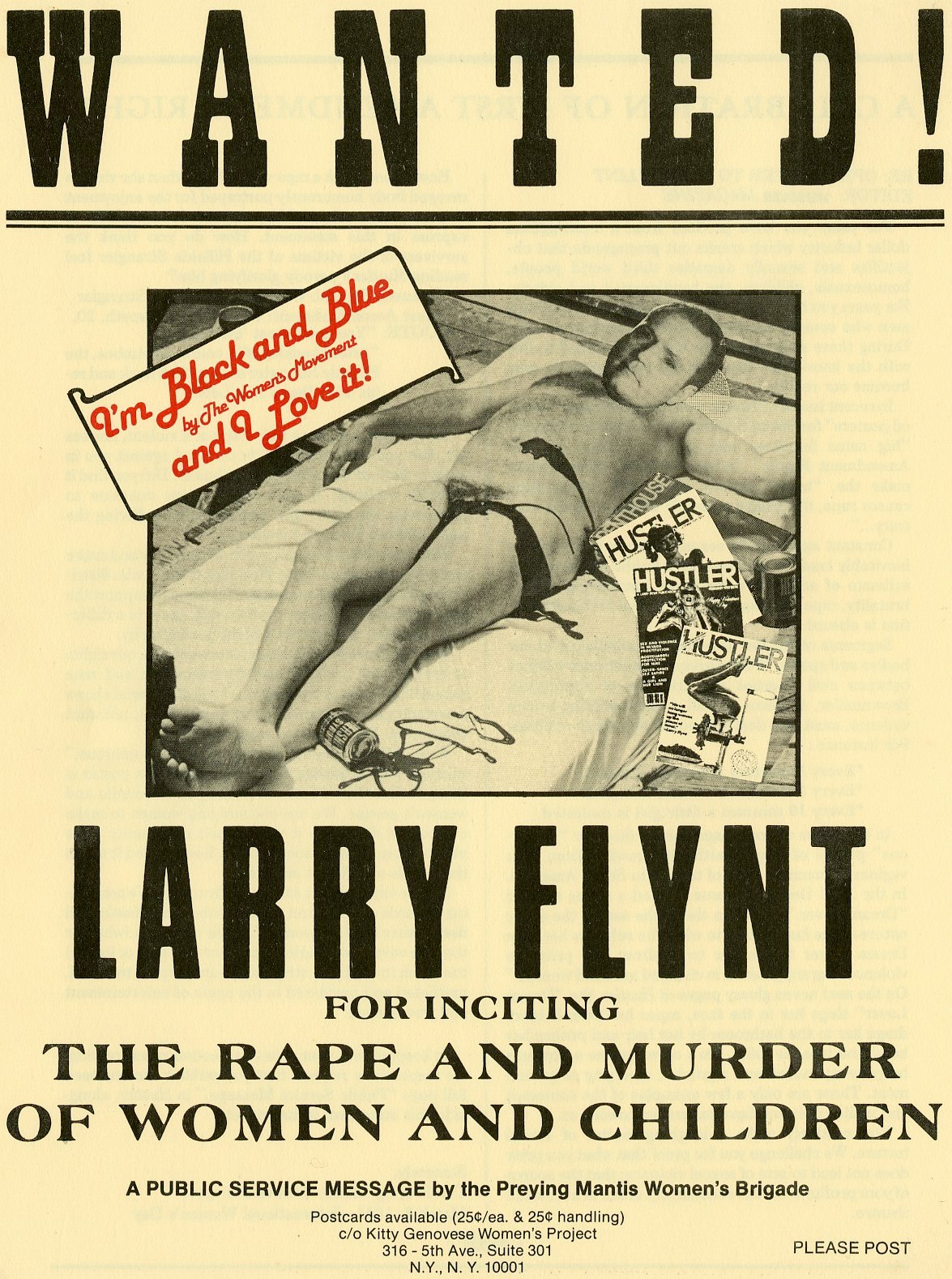

The feminist antipornography movement of the 1970s and 1980s began as an effort to expose and eliminate the increasingly sexist and violent imagery depicted in advertising and in mainstream media. The movement was concerned with images that portrayed women in submissive roles and that, when paired with violence, suggested that women found pain and violence pleasurable. The movement went even further in protesting that excessively violent pornography might lead to women being raped and murdered.

Women Against Violence Against Women, founded in 1976, avoided dealing with pornography because its members were concerned about oppressing free speech and endangering newly gained sexual freedoms. They focused on images and advertising in mainstream media, engaging in direct discussions with media corporations. One of the organization’s most notable campaigns was in reaction to an advertisement for the Rolling Stone’s Black and Blue album that featured the model Anita Russell, beaten and bound, with the phrase “I’m ‘Black and Blue’ from The Rolling Stones—and I love it!”

Women Against Pornography, founded in 1979, directly attacked pornography in print and film. Viewed by many as extreme, the group organized major protests against Hustler, Penthouse, and Playboy, attempting to block the distribution and sale of their magazines. This attack on pornography was met with resistance from other feminist and LGBT groups that encouraged discussion about the difference between pornography and erotica. Opponents feared that antipornography feminists were engendering support for the religious right and that antiobscenity laws would be employed to restrict women’s reproductive health, sexuality, and LGBT publications. Also troubling to many in this movement were the antipornography ordinances supported by Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon that would allow women to bring civil rights violation suits against pornographers; these lawsuits were ultimately unsuccessful.

Immigrant Women and Violence

Immigrant women often face special difficulty when confronted with physical violence or sexual assault. Speaking no English and ignorant of the legal system in America, some immigrant women are forced to suffer in silence, unaware that services are available to them. Instances of female illegal immigrants being held against their will—often forced to work 18 hours a day while suffering physical abuse under threat of deportation—are being reported in disturbingly high numbers. The status of women who have legally immigrated to the United States is often tied to their husbands’ status, which is compromised by allegations of domestic abuse. Frequently this results in deportation for the entire family. In response to the needs of these women, a number of grassroots and national organizations began creating informational pamphlets and offering services and legal assistance in a number of languages. Assistance to immigrant women is also provided through the Violence Against Women Act.