Women of the Blackwell Family: Resilience and Change

The Blackwells were a multigenerational family of abolitionists, entrepreneurs, educators, musicians, doctors, writers, expatriates, suffrage supporters, and women’s rights activists. The family was characterized not only by their ideals, but also by strong personalities and complex relationships.

This exhibition focuses on seven women of the Blackwell family from 1830 to 1950. Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman doctor in the United States, persevering through physical disability and societal obstacles. Her sister Emily became the third woman doctor in the United States and the dean of the Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary. Their sister Anna was more of a free spirit, a writer and translator who spent much of her life in France. Their mother, Hannah Blackwell, widowed in 1838 only six years after arriving in the United States, raised these independent women largely alone. Antoinette Brown Blackwell was an orator and the first woman minister in the country. Lucy Stone, known for refusing to give up her maiden name when she married, was an abolitionist, a tireless orator for women’s rights, and an editor and publisher of the Woman’s Journal with husband Henry Blackwell. Lucy’s daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, continued her parents’ suffrage work, becoming a leader in the movement for women’s right to vote.

The items selected for exhibition—from the library’s extensive collections of Blackwell Family Papers and related materials—highlight personal and professional relationships, including with many of the most important and influential thinkers of the 19th century. Considered collectively, they reveal a family who was always on the move and who—despite numerous hardships—turned their beliefs into action for the improvement of society.

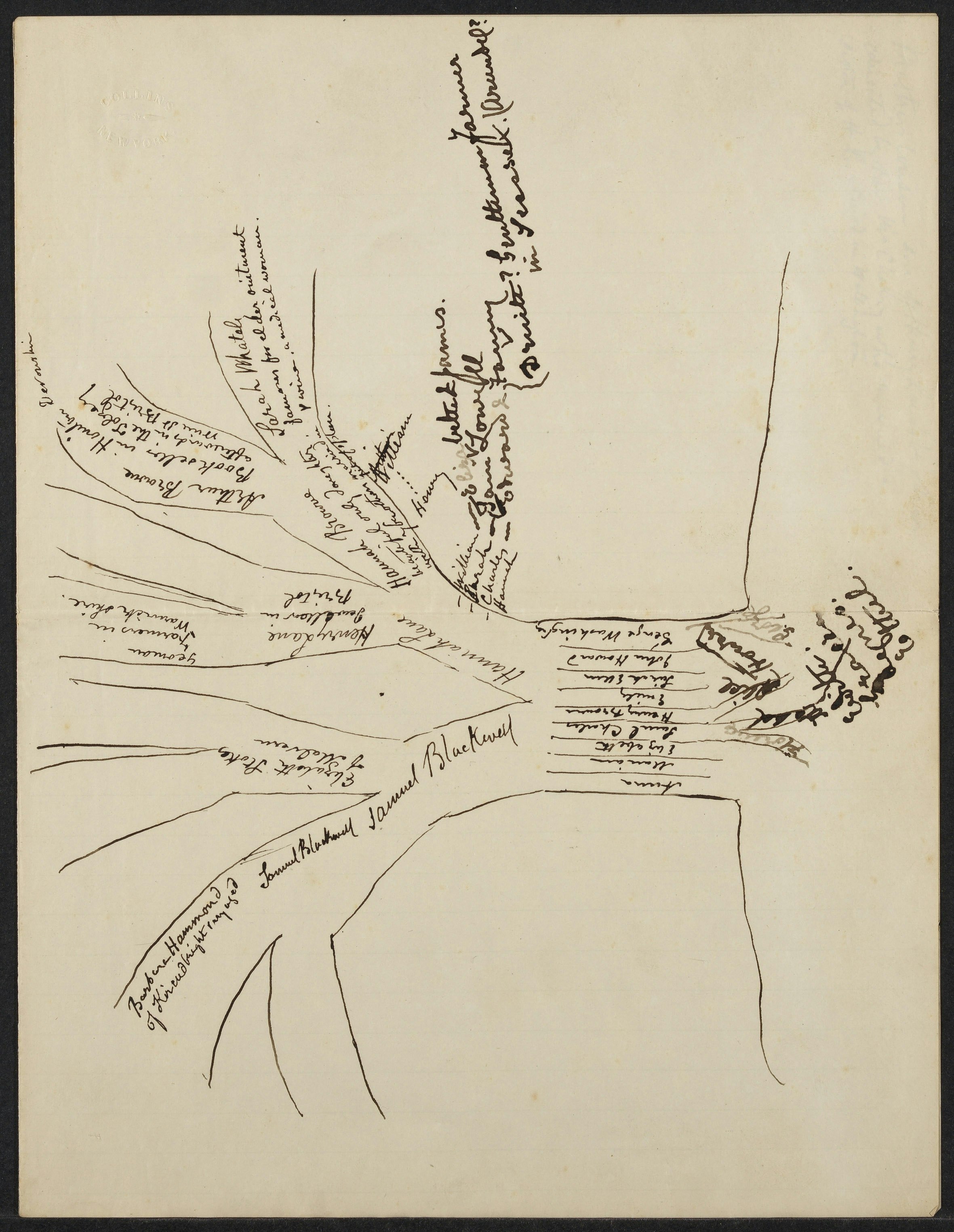

Samuel and Hannah Blackwell

Instilling love, family, a strong moral code, and—above all—a commitment to social reform, Samuel and Hannah Blackwell were parents to nine remarkable children. Constantly struggling for financial stability, the young family moved from England in 1832 to live in New York City and then New Jersey, eventually settling in Cincinnati.

Samuel (1790–1838), who worked in the sugar-refining business, dedicated himself to pursuing methods of refining the sugar beet because, unlike with sugar cane, slave labor was not used to cultivate the beet. Appalled by slavery and deeply committed to social reform, Samuel wrote frequently against the system. His essay “La Mancha” pointed out the hypocrisy of an American system touting freedom while so many were legally enslaved.

Hannah (1792–1870), widowed at age 46, was left with the challenges of raising her large family on her own. Deeply religious, she passed on her strong moral beliefs to her children in many letters and writings, including a family bible inscribed, “Oh! That this book may be to my dear George as a lamp to his path, and a guide to his feet, and an anchor to his soul.” Her signature on a petition in support of equal property rights for women conveys her commitment to social reform and rights for women.

Despite physical and financial upheaval, the Blackwell parents created a warm and loving family with deep and long-lasting ties.

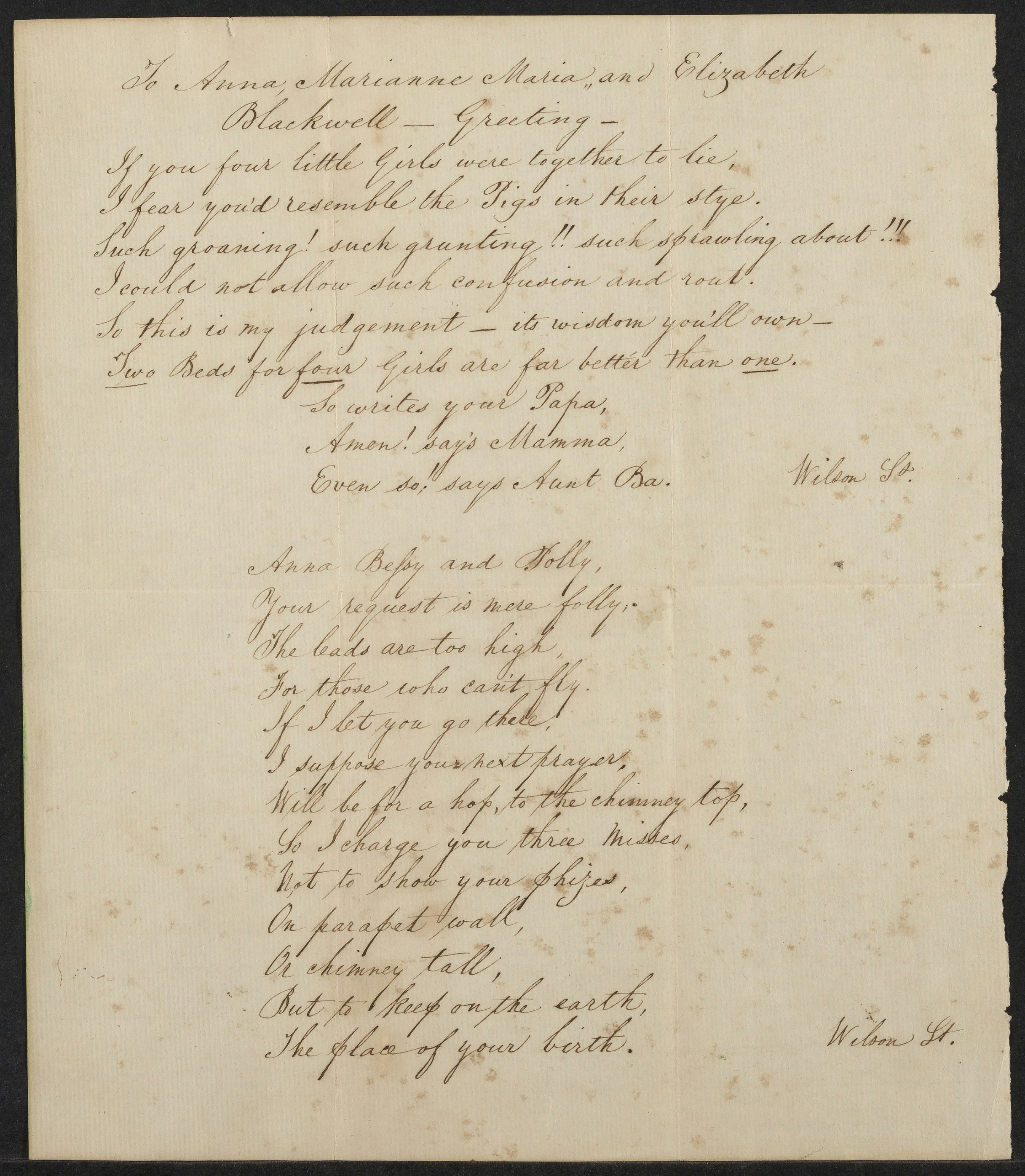

Anna Blackwell

Anna Blackwell (1816–1900) was the eldest child in the family and a dedicated Spiritualist. In 1845, she lived as a member of the Brook Farm utopian community in West Roxbury, Massachusetts. She later moved to France and translated the works of the French utopian socialist François Marie Charles Fourier and the novels of George Sand. She wore many professional hats during the course of her life: schoolteacher, writer, poet, translator, and journalist. She was a contributing correspondent for as many as 11 newspapers around the globe.

Anna was committed to bringing Spiritualism into the mainstream. The philosophic basis of Spiritualism includes the survival of the soul after death, the ability of the dead to provide guidance to the living, and seeing the natural world as an expression of God, or the “Infinite Intelligence.”

Writing in both English and French, Anna widely espoused her philosophy in published essays, articles, booklets, and poetry. In 1876, her prize-winning essay on Spiritualism was widely read, as evidenced by the letter from Edward Blyth discussing her philosophy of science and the arts. The legacy of her family’s commitment to social reform is seen in Anna’s 1898 essay, “Whence and Whither? Or, Correlation between Philosophic Convictions and Social Forms.”

In her poem “De Profundis,” she writes:

Then shall we know that every seeming Ending

Is but a new and happier phase Begun;

Extremes of orbed movement ever blending

In golden cycles round th’ Eternal Sun.

All shades beneath that Central Fire dissolving,

With raptured seraph-vision shall we range

Through singing worlds round His dear love revolving.

And say, “There is no Death; but only Change.”

Anna’s religious beliefs strayed from her more conventional upbringing but still echoed family ideals. In her essay “The Church of the Future,” she writes, “‘Stand away from injustice’ must be our motto.”

Elizabeth Blackwell

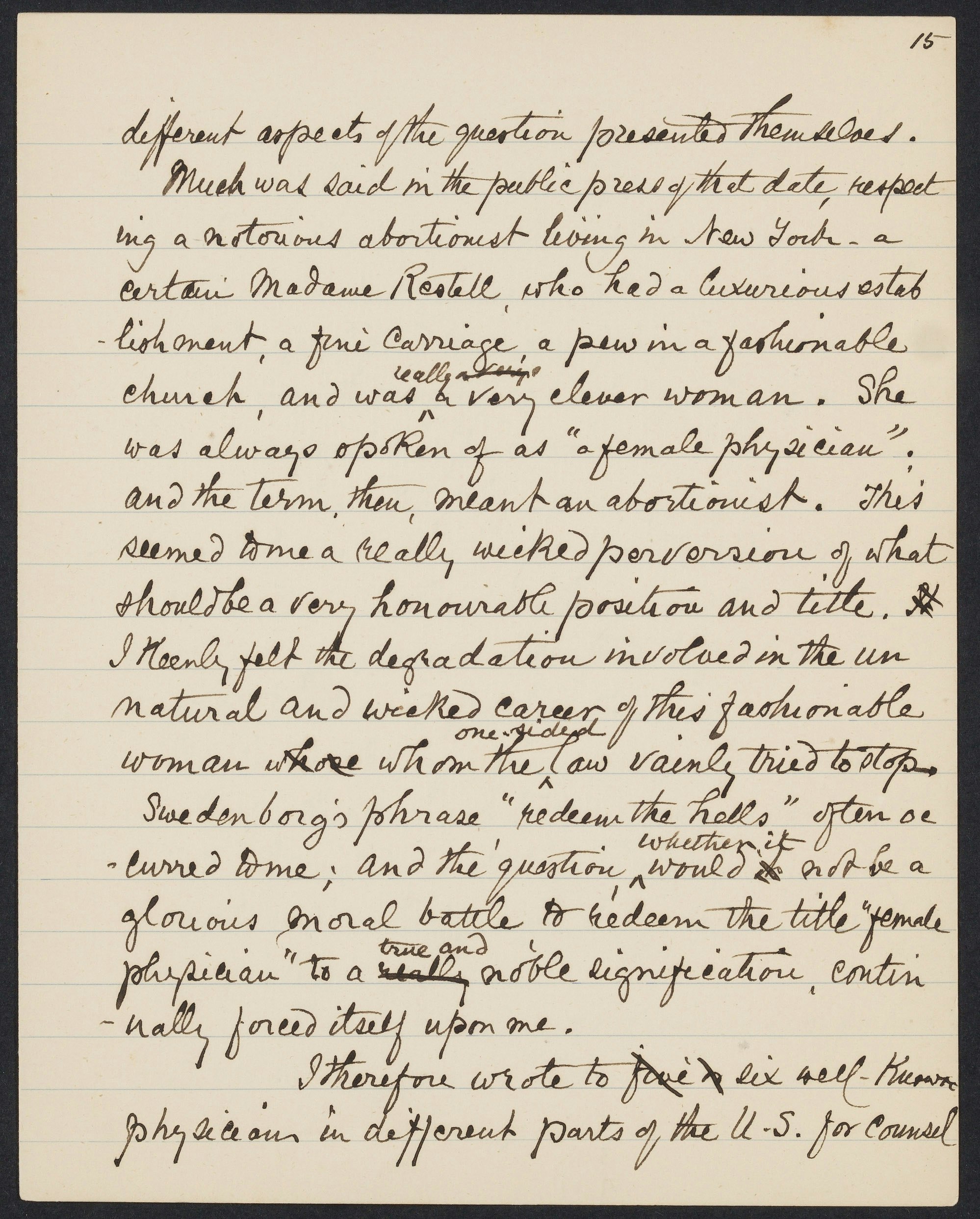

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910), a pioneer in the medical education of women, was the first woman in the United States to earn a doctorate in medicine. The third eldest Blackwell sibling, Elizabeth was 11 when the family emigrated from England and, despite becoming a naturalized American citizen, Elizabeth always felt English. She moved back to England permanently in 1869, eventually settling in Hastings.

Elizabeth’s childhood in Bristol, England, was marked by the strict Congregationalism of her parents, theologically conservative but profoundly committed to social reform. Later, during her early adulthood in Cincinnati, Elizabeth’s reform impulse was further influenced by Unitarian Transcendentalism and ultimately directed toward medicine. Steeped in a worldview that understood health and disease to be partially a function of an individual’s morality, Elizabeth believed that women’s superior moral sense made them well suited to medicine. Her primary interest lay in disease prevention through social hygiene and sanitation; she was never able to reconcile her moralistic view of medicine with the growing evidence of germ theory.

When Elizabeth received her medical degree, in January 1849, she was unable to find a hospital anywhere in the United States where she could acquire necessary clinical experience. She departed for further study in Paris but was barred from medical lectures, which were open only to men. Thus, Elizabeth started over as a student at La Maternité, a teaching hospital for midwives, where she was finally able to see patients. Tragically, while treating an infant for ophthalmia neonatorum—a disease acquired in childbirth from mothers infected with gonorrhea and then the most common cause of childhood blindness—Elizabeth accidentally infected her own eyes. Despite receiving the best medical care in Paris, Elizabeth lost sight in her left eye, and her right eye remained weak.

Elizabeth was aware of the limits of conventional medicine and was intrigued by the possibilities presented by such medical therapies as mesmerism, homeopathy, and hydropathy, but she recognized that her outsider status required her to stay within the bounds of the mainstream as a physician. As a patient, she tried mesmerism to improve her sight, to no avail. Next, Elizabeth went to Bad Gräfenberg to take the water cure from Vincenz Priessnitz, the father of 19th-century hydropathy. Unimpressed with much of her treatment, Elizabeth’s opinion sank even lower when her left eye became severely inflamed, requiring its surgical removal and dashing her remaining hopes of practicing surgery.

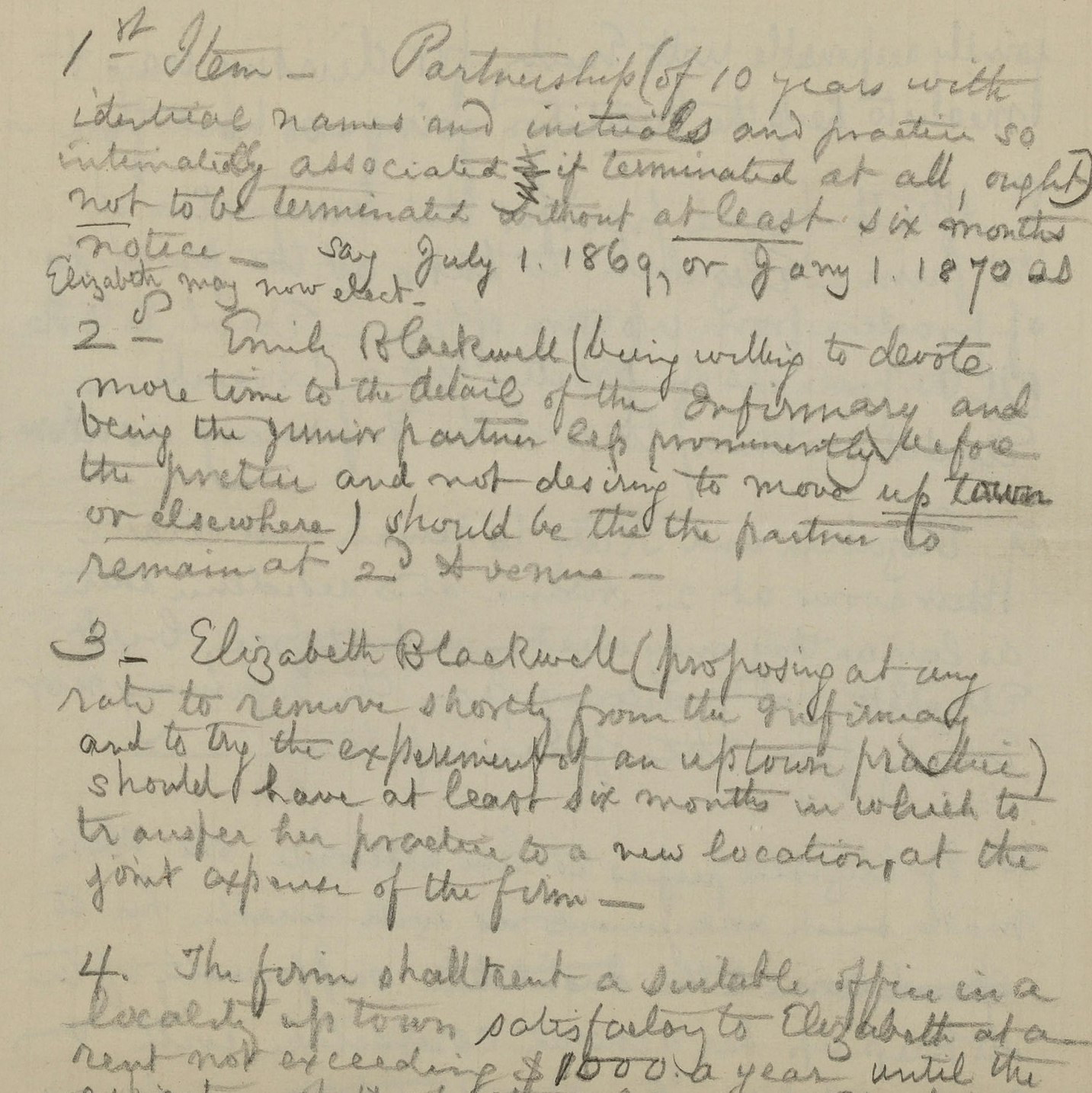

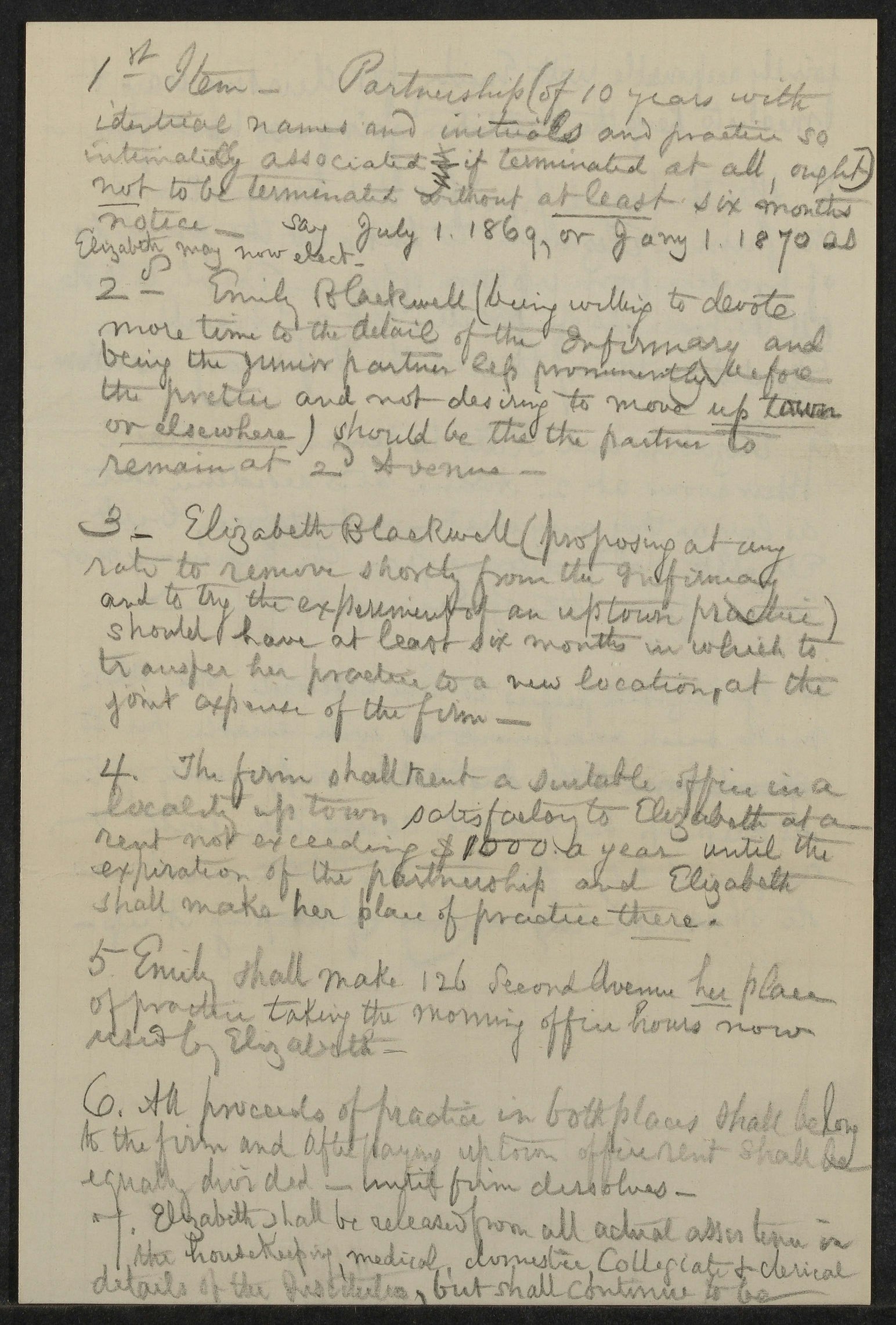

Elizabeth practiced medicine to secure her livelihood, but she was always more interested in larger social reform than she was in individual patients. Deeply committed to holding open the door for other women to follow her into medicine, Elizabeth and her sister Emily established first a teaching hospital, the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children, to give women doctors clinical experience and later the Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary, to ensure a high caliber of medical education for women. In England, Elizabeth was one of the founders of the London School of Medicine for Women. Although her tenacity brought these institutions into being, she left these organizations to flourish under the leadership of others, unable to accept the compromises necessary for successful collaboration.

Emily Blackwell

Emily Blackwell (1826–1910) followed in her elder sister’s footsteps, becoming the third woman in the United States to earn a medical degree. Her path was more arduous than that of Elizabeth, as medical colleges reacted to keep women out by the time of Emily’s educational pursuits. Following her graduation in 1854 from Case Western Reserve University, where she was the only woman in her class, Emily traveled for two years in the United Kingdom and Europe to further her studies and gain surgical skills. After her return to the United States, she went to work in the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children, the small charitable institution founded in 1853 by Elizabeth. The two sisters and their associate, Dr. Marie Zakrewska, rapidly grew the dispensary into the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. It was staffed with women physicians and provided a place for them to gain the clinical experience denied them in male-controlled institutions.

The doctors Blackwell chartered the way for women in medicine in 1868 by opening the Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary. Elizabeth left for England not long after the college’s founding, thereby leaving Emily to manage both the college and the hospital. An excellent administrator, Emily served as the longtime dean, developing a first-rate, pathbreaking school with the highest academic standards. Among the 364 women to receive degrees was Eliza Bowen Phelps, who was in the first class of five students to graduate from the college. When the college closed in 1899, the students were transferred to Cornell University Medical College. Anna C. de la Motte was one of the last students, having begun her education at the Woman’s Medical College but graduating from Cornell.

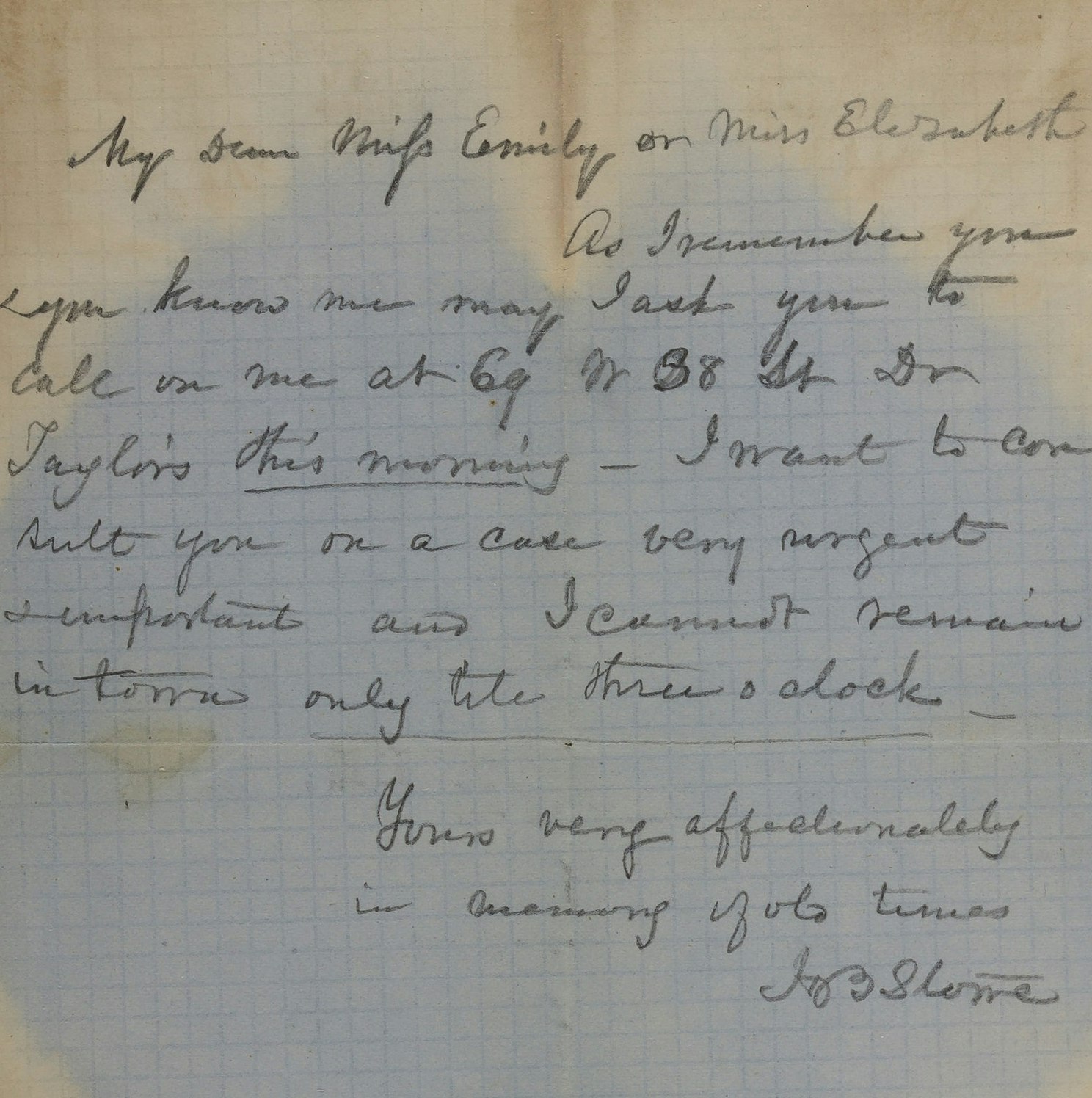

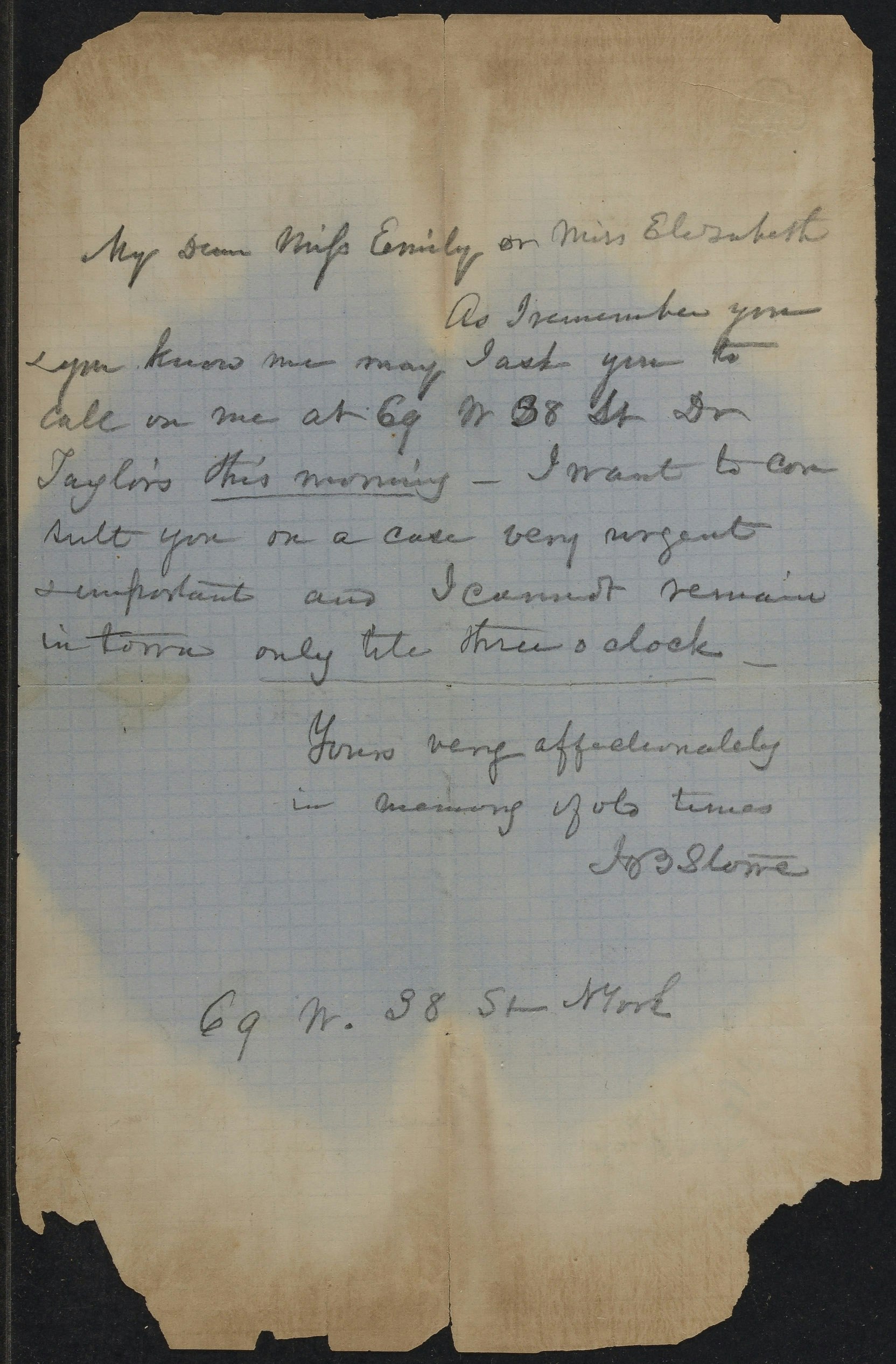

The Blackwells had high-profile social ties, such as with Harriet Beecher Stowe, who was a neighbor in Cincinnati. Although she enjoyed close familial relationships and a full professional life, Emily’s domestic life took much longer to develop. Like her sisters, Emily never married, and also like her sisters Elizabeth and Sarah (known as “Ellen,” her middle name, by her family), she chose to adopt. Emily’s daughter Anna (also known as “Hannah” or “Nannie”) came to live with her in 1871. In 1882, Elizabeth Cushier, a graduate of the Woman’s Medical College and later a member of its faculty, became Emily’s domestic partner. Elizabeth and Emily shared 28 years together, living in New York City and in Montclair, New Jersey, and summering in York Cliffs, Maine.

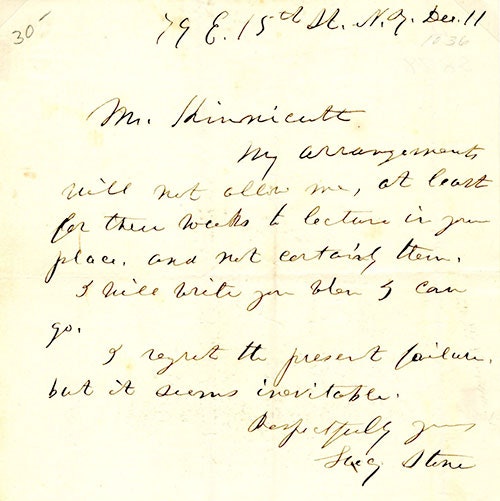

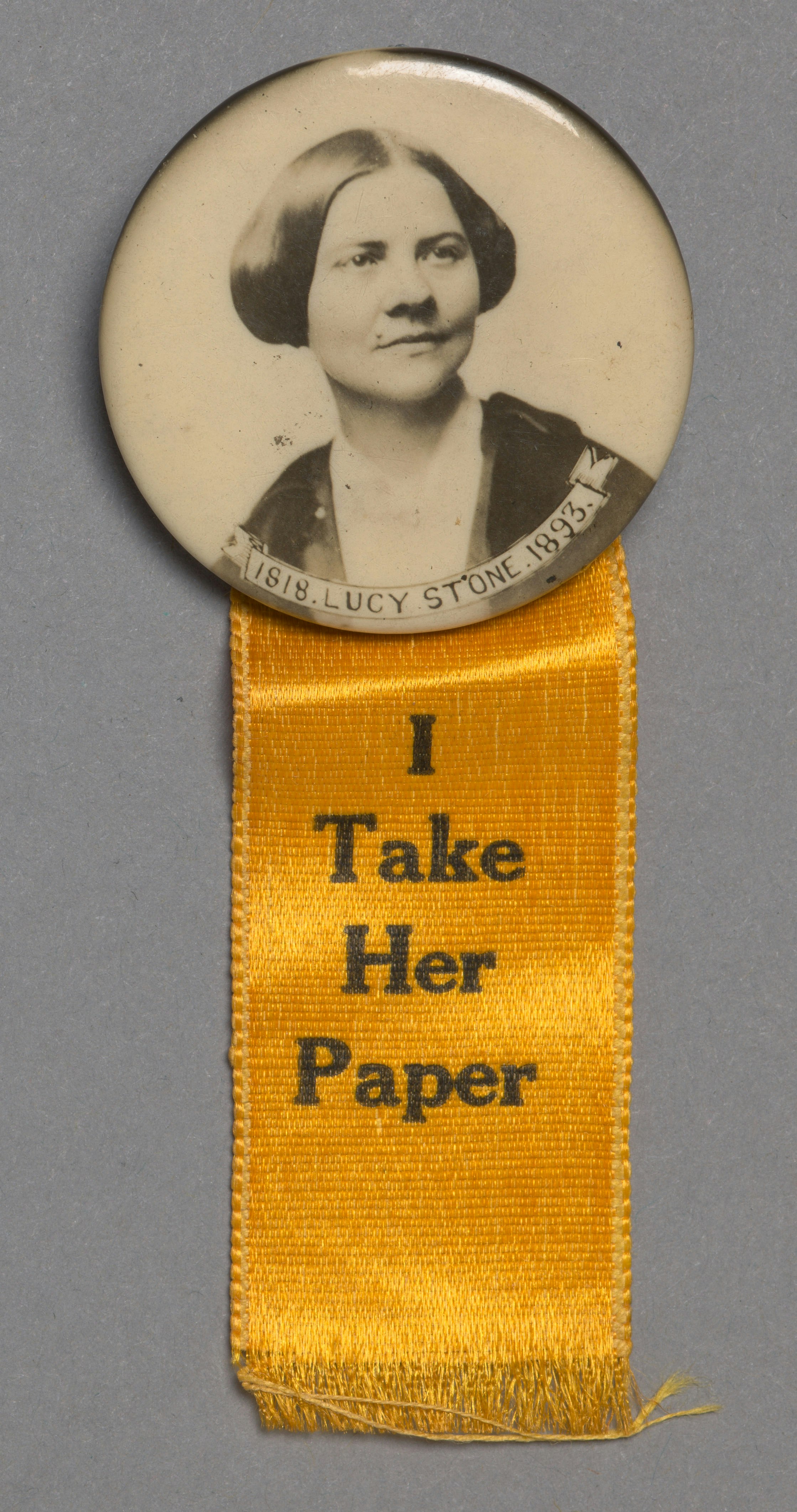

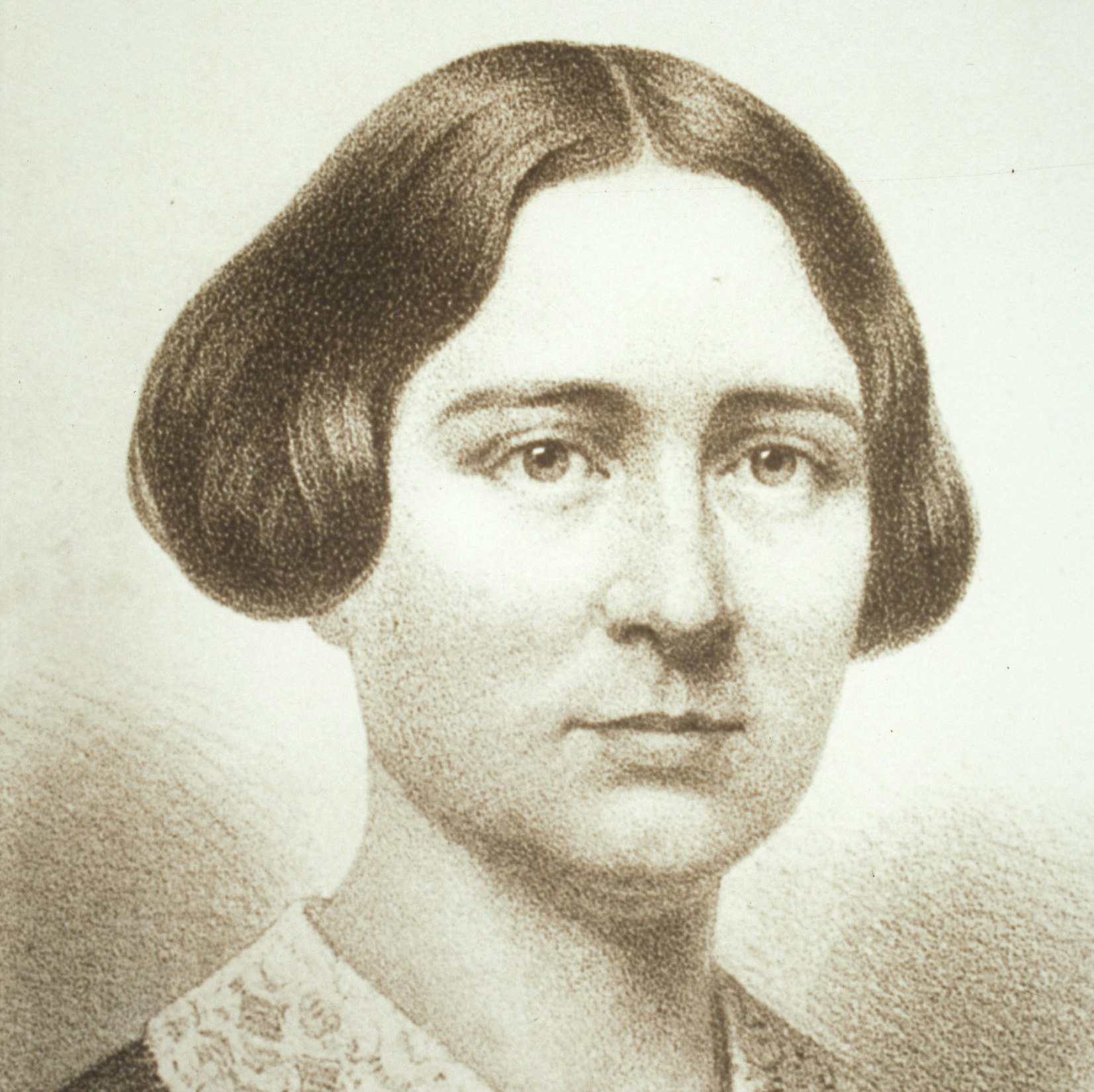

Lucy Stone

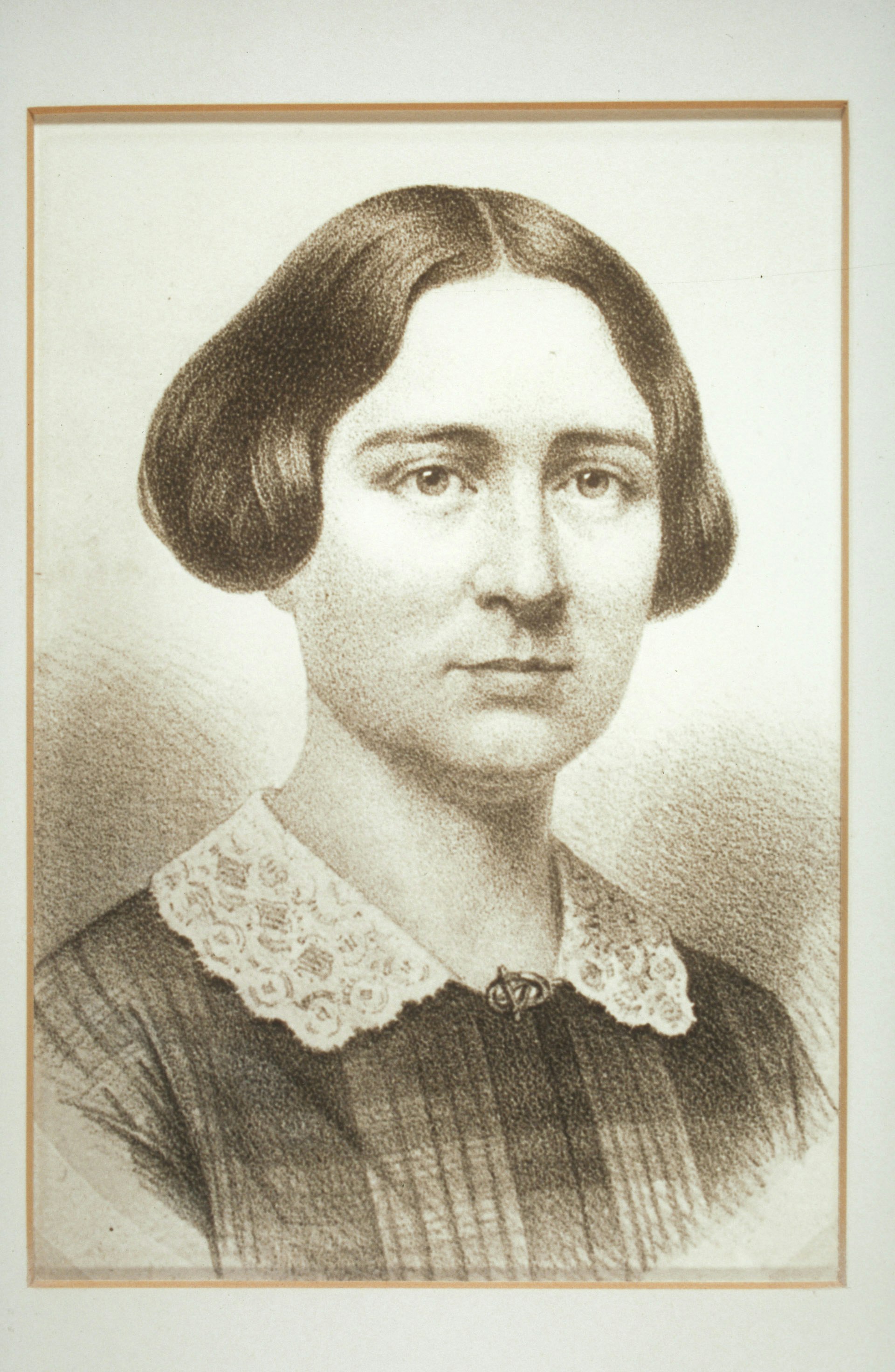

Born in West Brookfield, Massachusetts, Lucy Stone (1818–1893) was raised on the family farm. Without parental support, she financed her way to Oberlin College, where she honed her oratorical skills. At age 29, she became the first woman from Massachusetts to receive a college degree. While at Oberlin, she met Antoinette “Nettee” Brown, who would become a lifelong friend and her sister-in-law. After graduation, Lucy became popular on the antislavery lecture circuit and as a woman’s rights speaker. Not only was she compelling in her oratory, Lucy was also visually striking. At one point, she cropped her hair and wore the controversial bloomer dress—an outfit with, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, “a short jacket, a skirt extending below the knee, and loose ‘Turkish’ trousers, gathered at the ankles.”

Determined to never wed, Lucy was nevertheless persuaded to marry Henry Browne Blackwell in 1855, after a two-year courtship. Henry shared her passion for abolition and suffrage causes, and both felt strongly that marriage laws were oppressive to women. Resolving that their matrimonial relationship would be based on equality, they wrote a protest that was read at their wedding ceremony and subsequently published in the newspaper. Setting a precedent, Lucy kept her maiden name after marriage. Women who followed this convention would thereafter be known as “Lucy Stoners.”

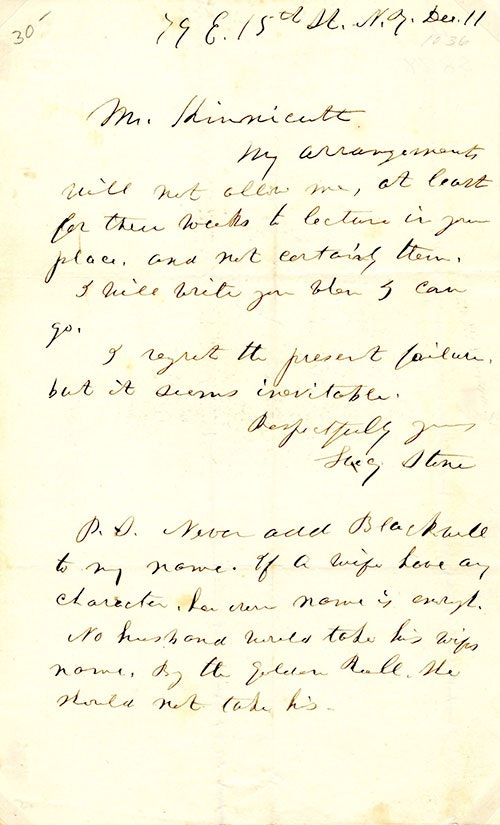

Lucy and Henry were partners in the suffrage battle. Together and individually, they campaigned for the vote for women throughout the United States. Regarding the issues of black suffrage and woman suffrage, they supported the 15th Amendment, thereby breaking with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who opposed it. In response to the launch of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association by Stanton and Anthony, Lucy and Henry became principal founders of the American Woman Suffrage Association and, later, the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. They started and for decades nurtured—through writing, editing, and financing—what would become the leading suffrage publication, the Woman’s Journal. Primarily a businessman, Henry was loyal to the couple’s shared causes, if not always loyal to their marriage. His relationship with “Mrs. P.” (presumed to be Abby Patton, a business partner’s wife and a fellow abolitionist and suffragist) was clearly distressful to Lucy and to Henry’s sisters. Additionally, Henry’s business dealings caused financial hardship to his family.

A devoted mother, Lucy stepped aside from her lecture activities to care for her daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, after her birth in 1857. Alice grew up to have a very close relationship with her parents and continued their suffrage work as an adult. She kept her mother’s memory alive by writing her biography. Likewise memorializing Lucy, Maud Wood Park, the donor of the suffrage collection on which the Schlesinger Library was founded, wrote a play based on her life. Among its productions was one by the Federal Theatre Project of the Works Progress Administration, at Boston’s Copley Theater, in 1939.

Antoinette Louisa Brown Blackwell

Antoinette Louisa Brown Blackwell (1825–1921) was born in Henrietta, New York. When Antoinette was a child, her parents joined the Congregational church, and she preached there as a teenager. In 1846, she enrolled at Oberlin College, using earnings from working as a teacher for four years. There, she studied English and took courses in theology. Despite her having taken the required classes, Oberlin disallowed Antoinette from graduating with a theological degree (later in her life, the school would award her an honorary doctorate and embrace her as an exceptional alumna). It was at Oberlin that Antoinette met Lucy Stone.

In 1852, Antoinette became the first woman ordained as a Protestant minister in the United States when she was appointed to the Congregational church in South Butler, New York. She stayed in the position for only one year, feeling isolated in her role and doubting the orthodox doctrine that she was expected to preach. This doubt is reflected in her later books, including The Social Side of Mind and Action (Neale Publishing Company, 1915). In subsequent years, Antoinette supported herself through public speaking engagements and her published writing. One of her books even prompted a reply from Charles Darwin.

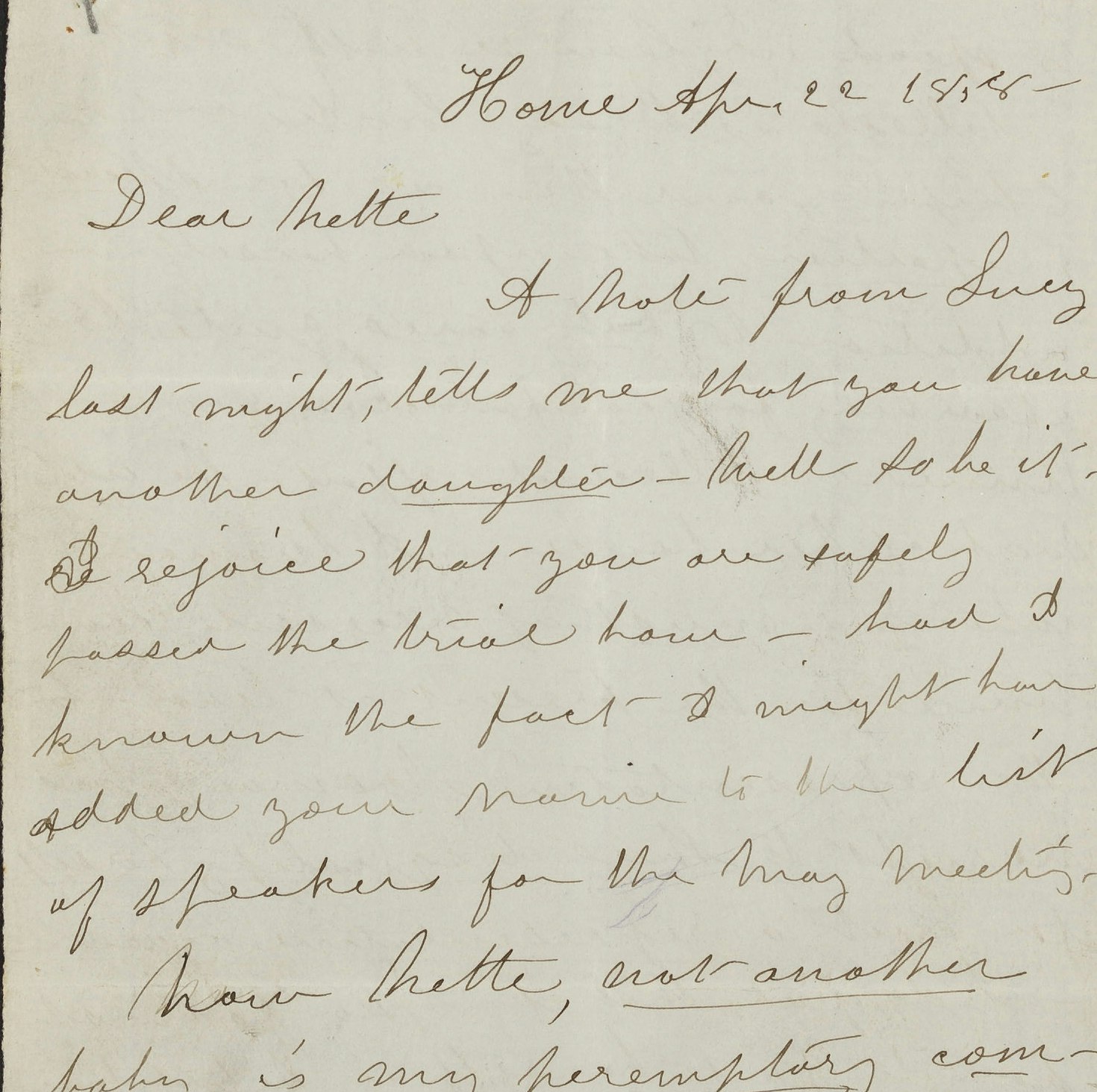

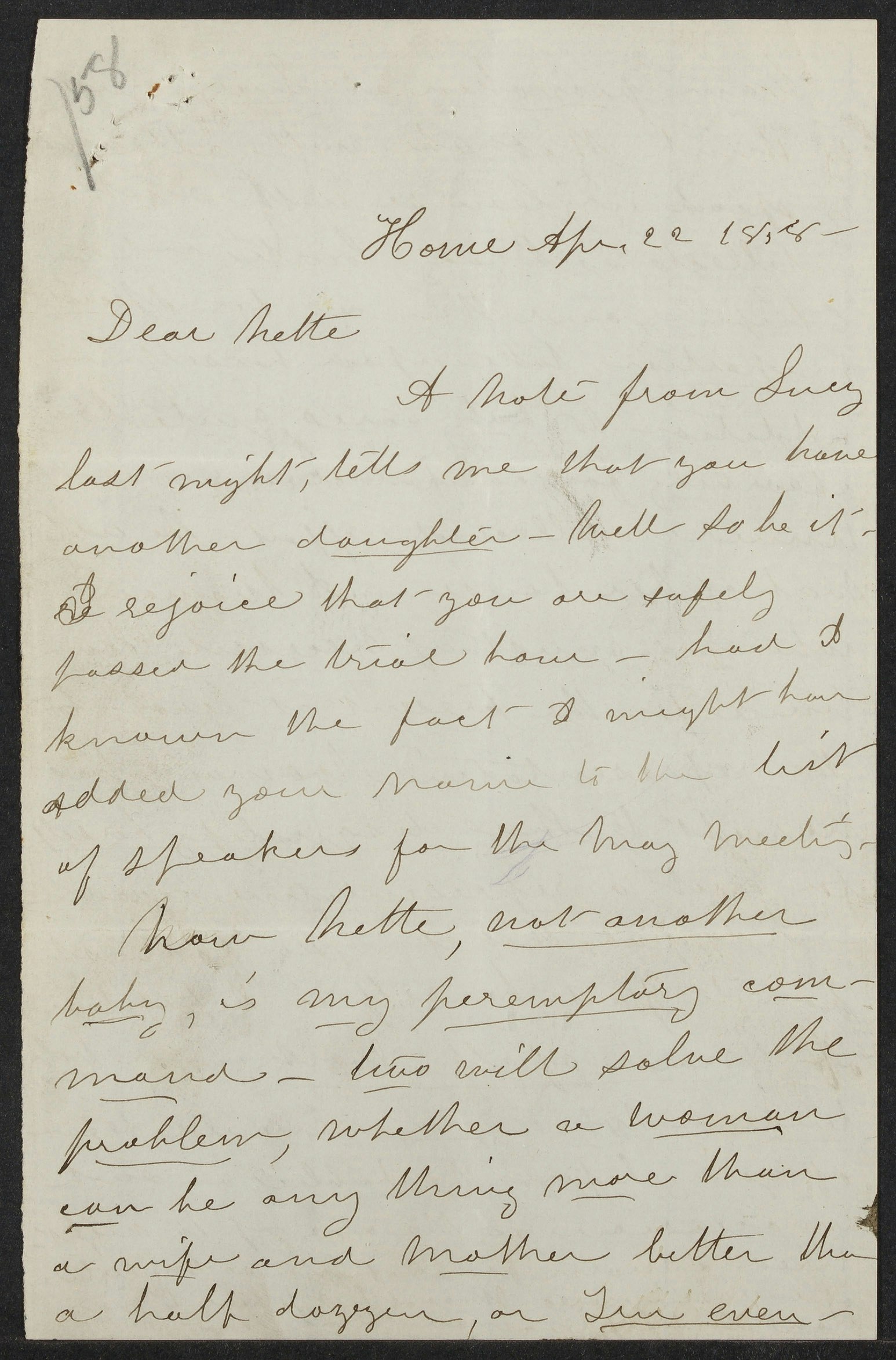

Antoinette often wrote to her friend Lucy’s brother-in-law, Samuel Blackwell, and despite initially rejecting the idea of marriage, she changed her mind. They married in 1856 and—despite Susan B. Anthony’s admonitions to stop at two children—had five daughters. Antoinette and Samuel worked together both inside and outside of the home, and Antoinette often wrote about work-life balance.

Because of her domestic responsibilities, Antoinette spoke less and wrote more while raising children. She was a prolific writer for the New-York Tribune and a good friend of its publisher, Horace Greeley. She wrote six nonfiction books, mostly combining philosophy and theology, along with a novel and a book of poems.

Later in life, Antoinette returned to organized religion and became a Unitarian minister. She continued to speak publicly, attend conferences, and establish new organizations supporting suffrage and women in the Unitarian Church. At the same time, she split with the National Woman Suffrage Association because of disagreement over the 15th Amendment: Antoinette supported the amendment that allowed African Americans the right to vote even though the same right was not extended to women.

Antoinette lived long enough to see the 19th Amendment pass and to vote in the election that followed. Toward the end of her life, she was a frequent and honored guest at suffrage parades.

Alice Stone Blackwell

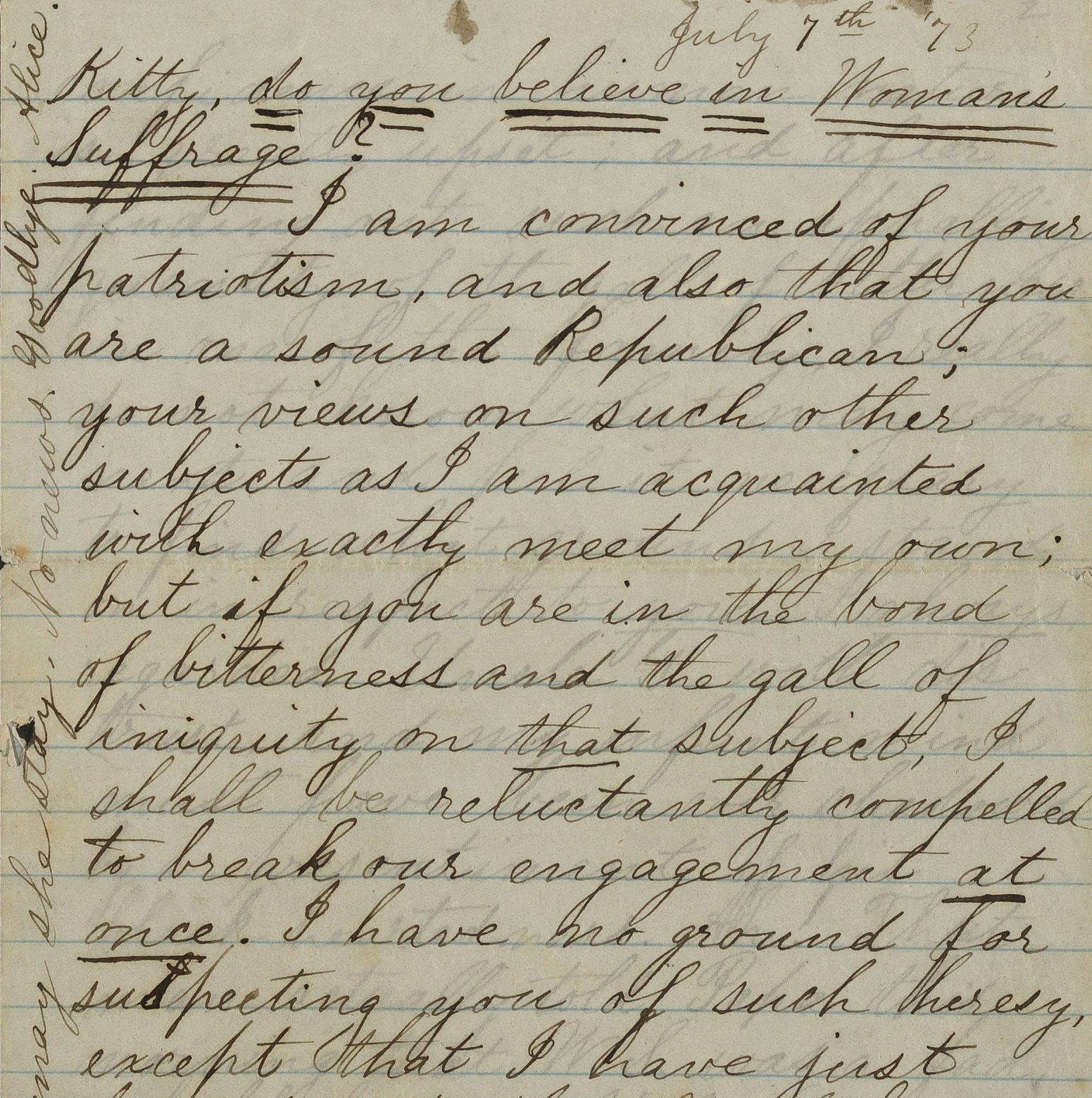

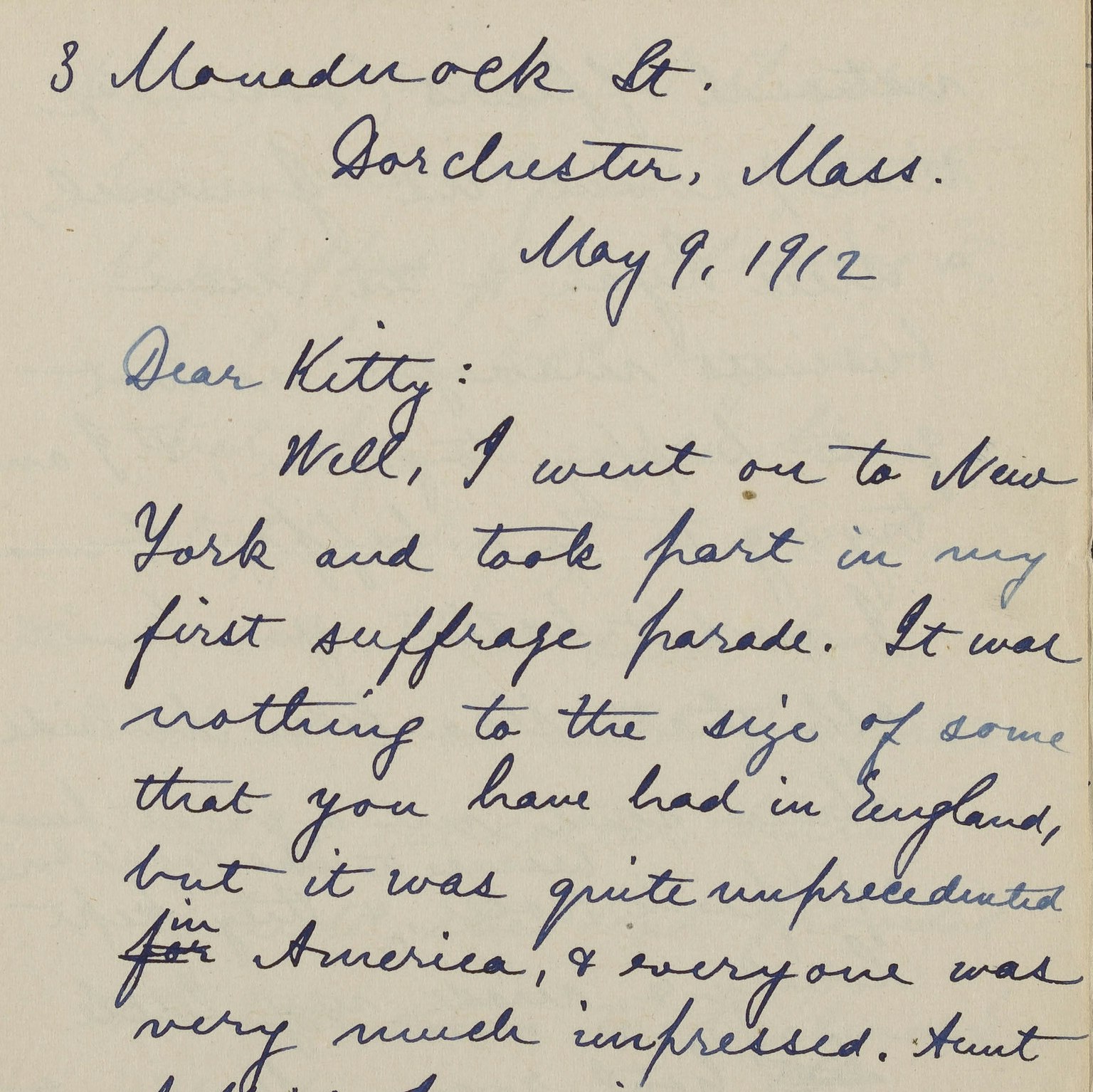

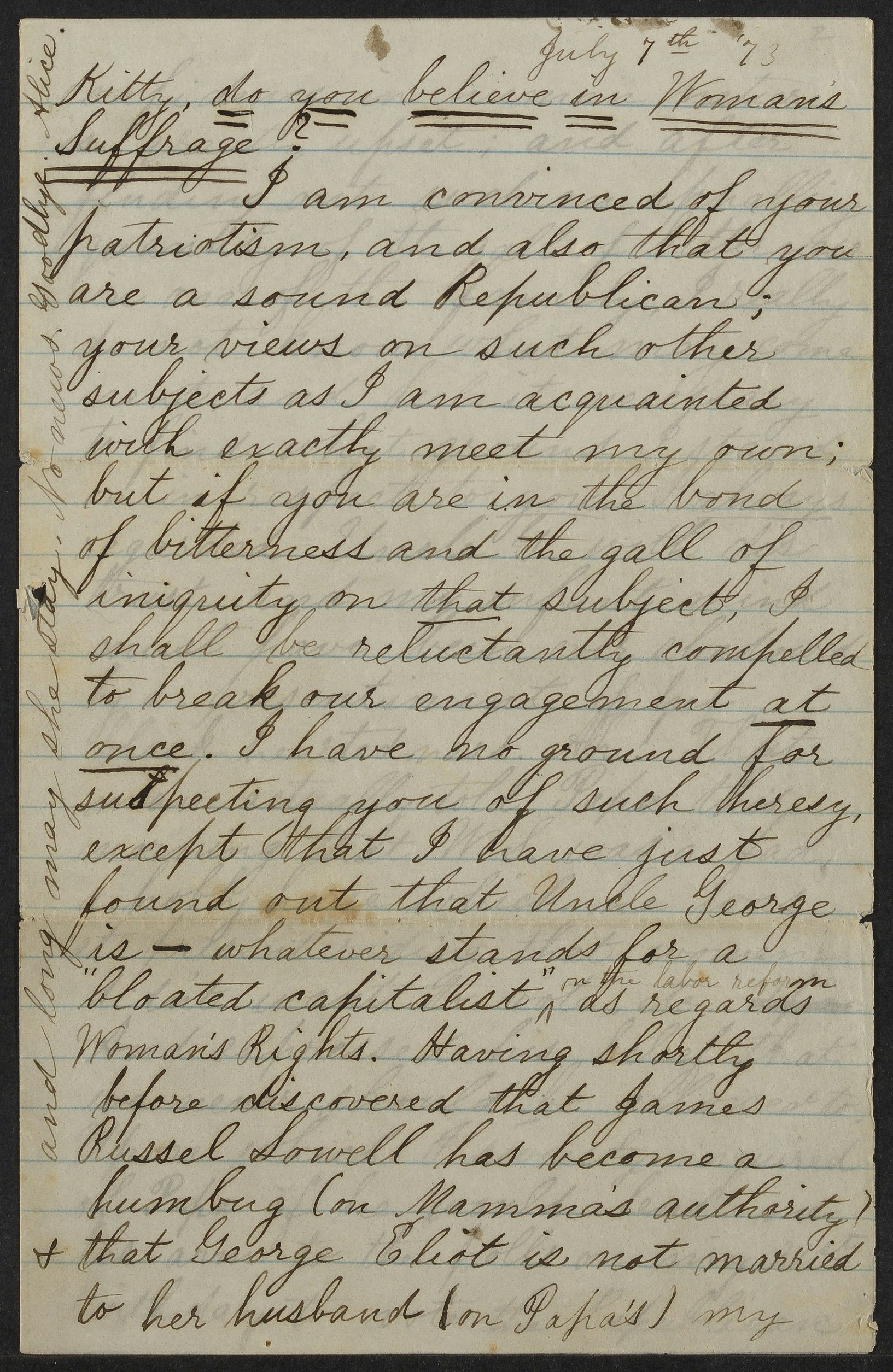

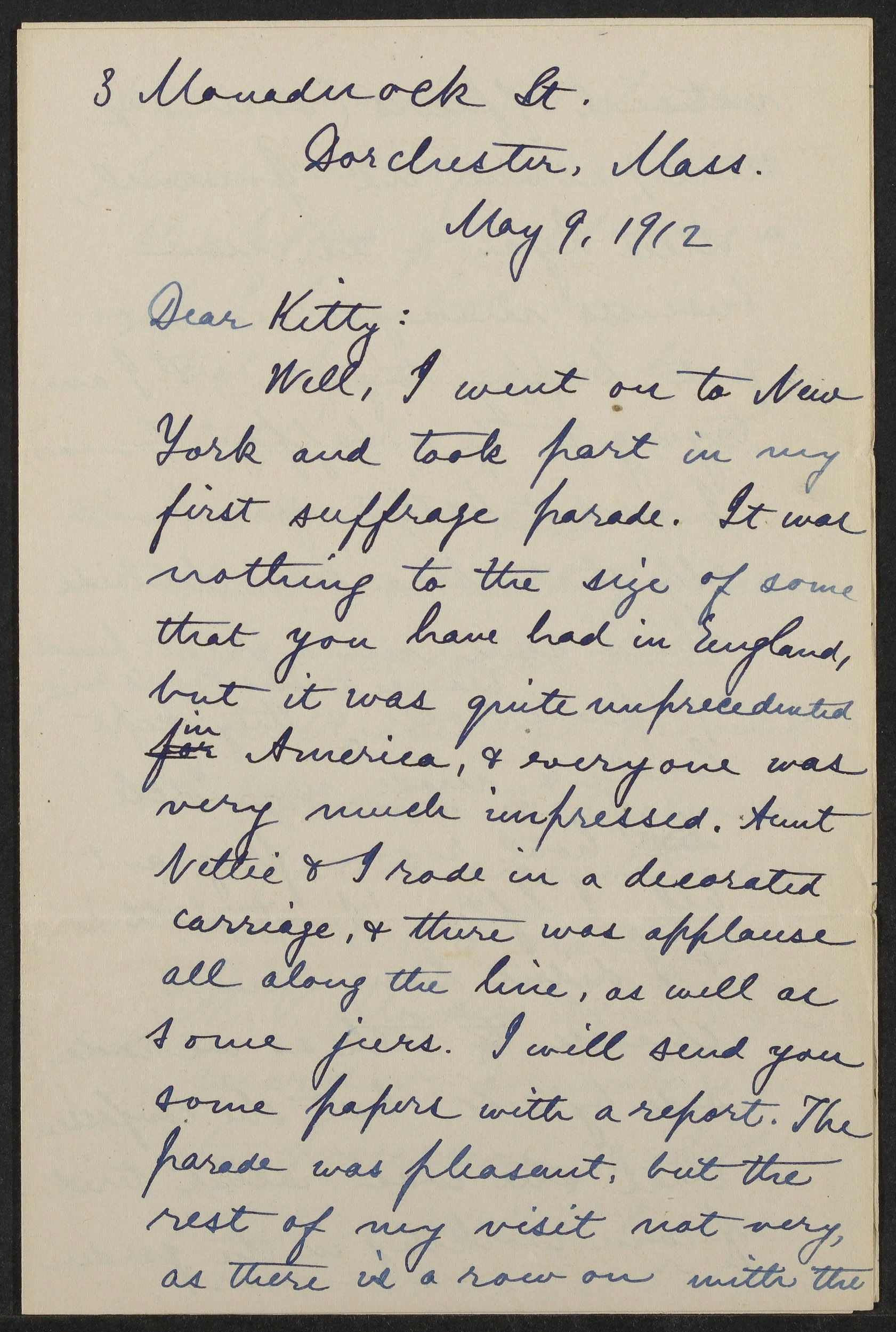

Alice Stone Blackwell (1857–1950) was the only child of women’s rights activists Henry Browne Blackwell and Lucy Stone. Often left with relatives while her parents traveled for work, she developed close relationships with many of her Blackwell cousins, especially with Katharine “Kitty” Barry Blackwell, Elizabeth Blackwell’s adopted daughter. Alice kept house with Kitty for the last 17 years of Kitty’s life.

Alice followed in her famous parents’ footsteps, dedicating much of her life to women’s suffrage. By age 16, she was writing for the Woman’s Journal, and by 26, Alice was an editor. Beginning in the late 1880s, she also edited the Woman’s Column—a suffrage newsletter originally sent to newspaper editors for republication in the mainstream press. During the same period, Alice worked to reconcile the American Woman Suffrage Association and the National Woman Suffrage Association. The merger of the two organizations took place in 1890, forming the National American Women Suffrage Association; Alice served as its recording secretary for nearly 20 years.

When her mother died, in 1893, Alice took over Lucy’s role as editor in chief of the Woman’s Journal. Around this time, Isabel Chapin Barrows introduced Alice to an Armenian named Ohannes Chatschumian (also transliterated as Hovhannes Khachumian) and to the rapidly deteriorating situation of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Alice and Ohannes collaborated on the translation of Armenian poetry and founded the Friends of Armenia to raise awareness and to support the settlement of traumatized refugees. Throughout her later life, Alice used poetry and the skills she gained as a suffrage organizer and journalist to further a wide range of humanitarian and progressive causes.