Altered Gazes

Altered Gazes foregrounds women as creators and consumers of countercultural content. In addition to materials from our growing collection of comics, zines, erotica and pornography, and other alternative publications, the exhibition features materials from the Ludlow Santo Domingo Collection, one of the largest gatherings of underground, alternative, and pop-culture publications in the world, which is shared among various Harvard libraries. Presented as a companion to Houghton Library’s concurrent exhibition Altered States: Sex, Drugs, and Transcendence in the Ludlow-Santo Domingo Library, Altered Gazes reframes past and present countercultures by highlighting women’s participation and responses.

The works presented in Altered Gazes offer a response both to mainstream society and to the male-dominated countercultural spaces in which they were created. Through small-press and self-published materials—from the aforementioned zines and comics to marijuana cookbooks, musical recordings, and sexually explicit magazines and films—women repurpose the styles and subjects of popular culture to express themselves, to comment on gender roles, and to educate their own communities. Although underground comics, X-rated publications, and popular music have often objectified and marginalized female participants, this exhibition highlights instances where women take charge of the gaze, creating culture instead of merely consuming it.

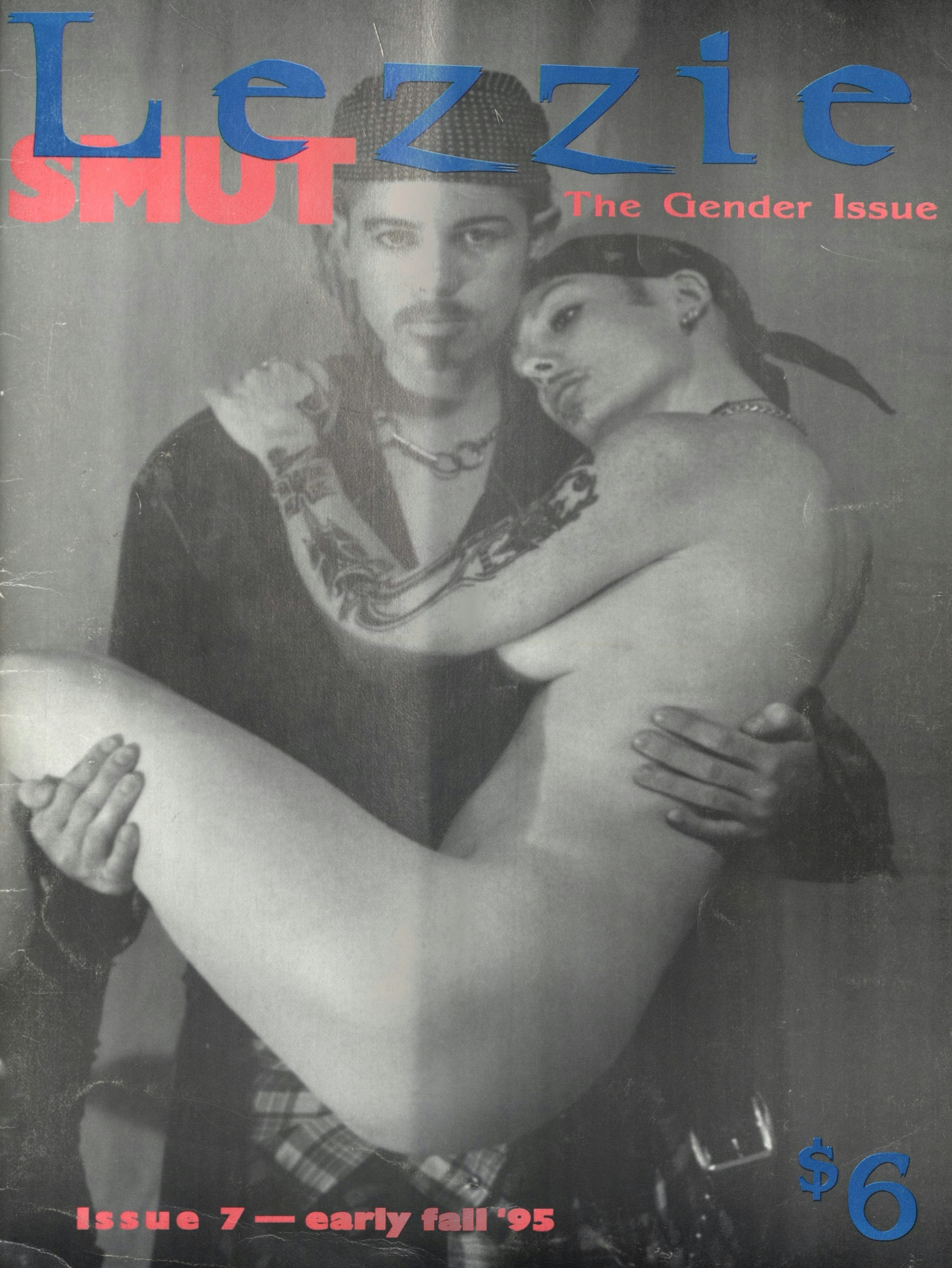

Sexuality

As commercially produced pornography made by and for men became more broadly available through new forms of mass media in the late 20th century, increasing numbers of women used these same media to create their own pornography and sexually explicit material, by and for women. Many were intentionally creating feminist sexualities, and they viewed sexual freedom and satisfaction for women as a necessary component of dismantling patriarchy. Some feminist porn producers, like Annie Sprinkle and Candida Royalle, were originally actors in pornography for men; others, like Petra Joy, come from more traditional filmmaking backgrounds. Glossy magazines like On Our Backs (the title parodying iconic feminist periodical Off Our Backs) and Lezzie Smut celebrate lesbian sex for lesbians, while zines provide sex positive sex education and a safe place to explore the joys and complications of human sexuality.

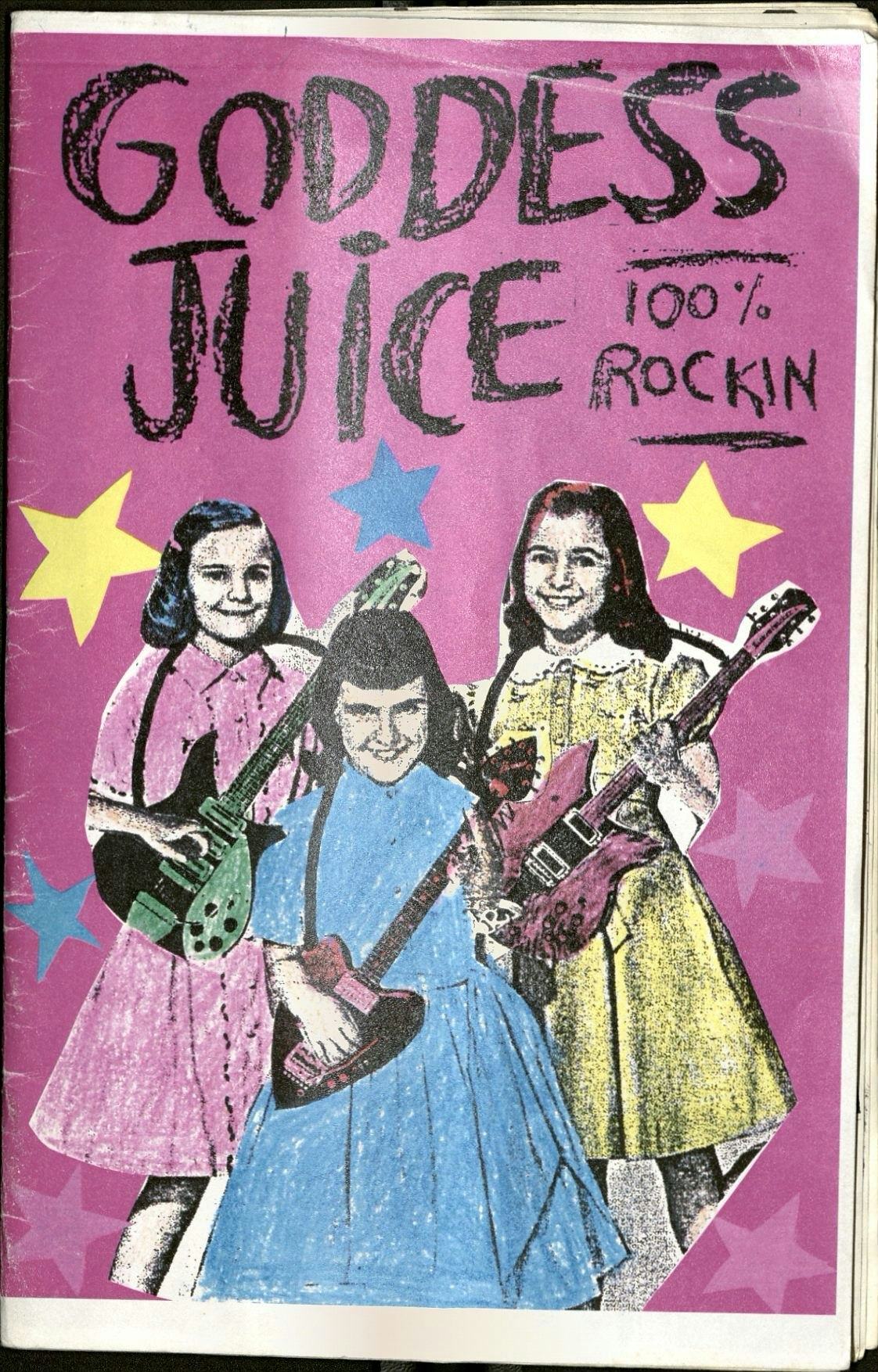

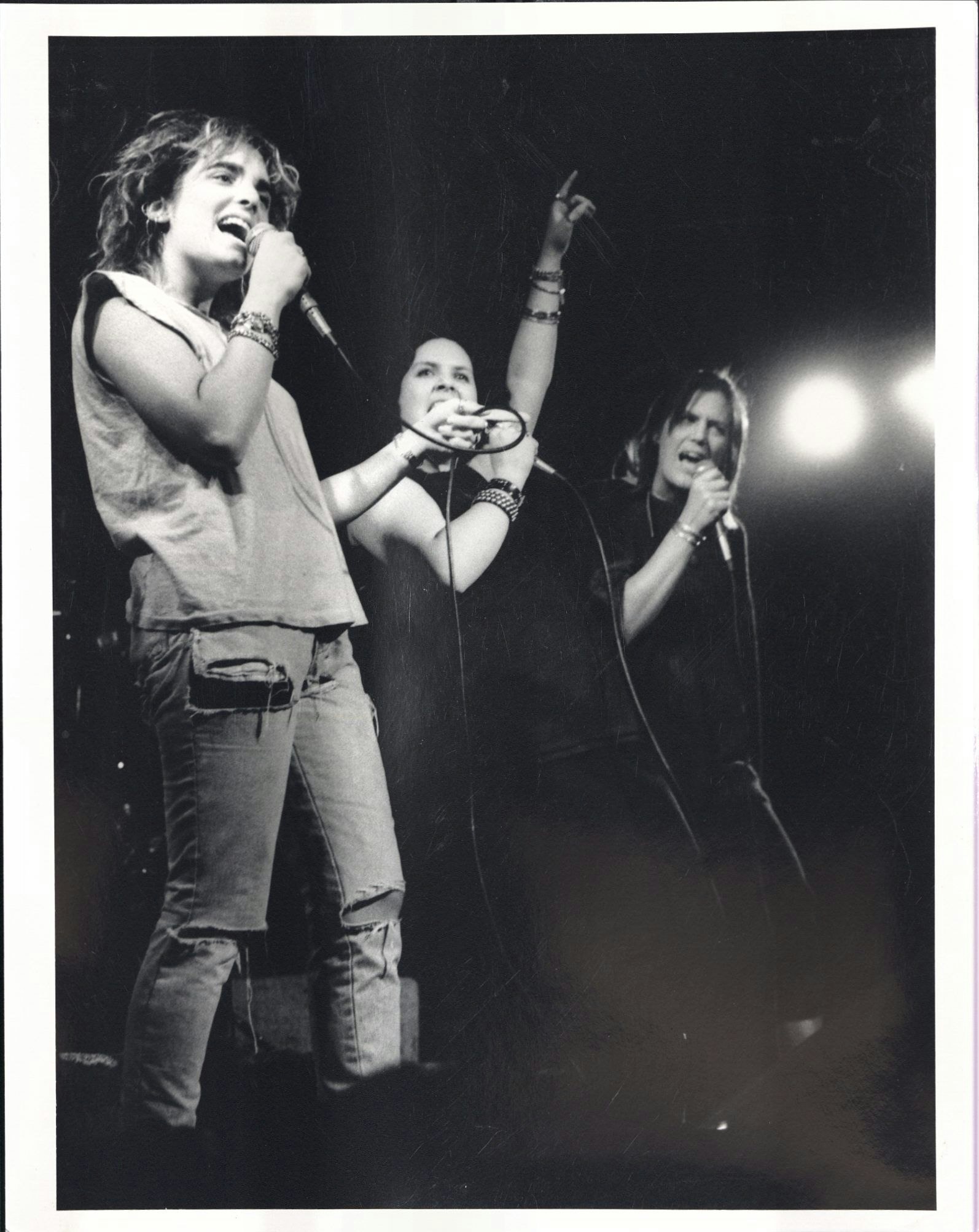

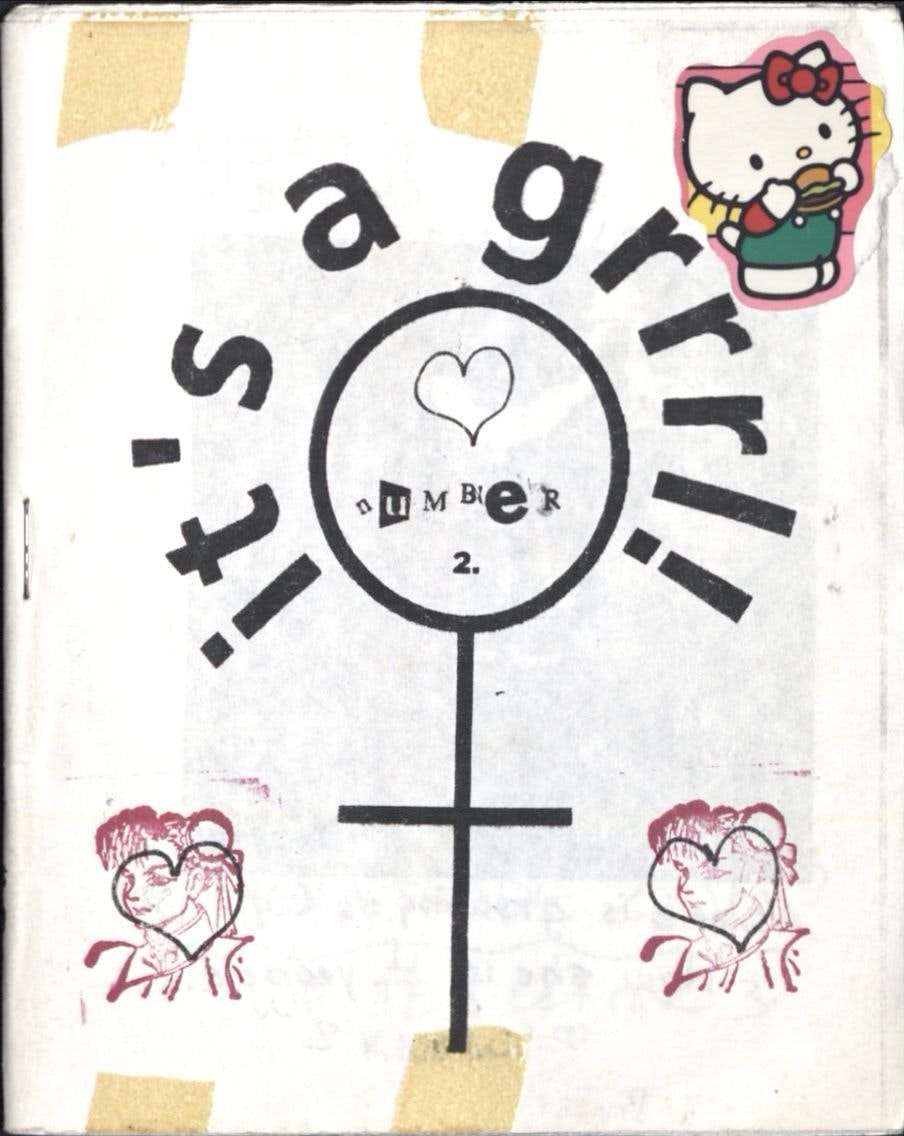

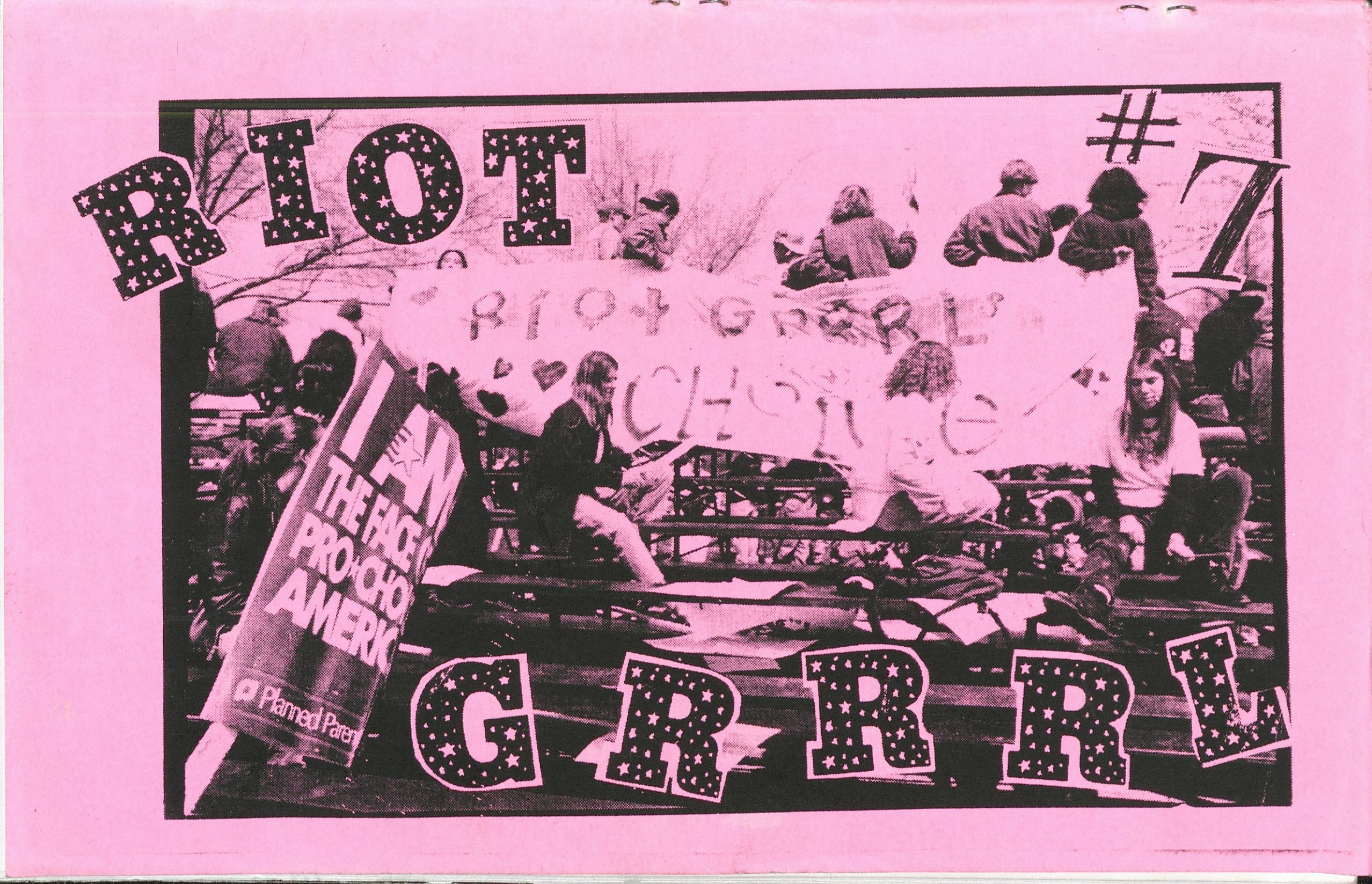

Music

Since the 1970s, women and girls have struggled to claim a place in male-dominated punk culture as performers and participants, and much like earlier generations of women, many punk women construe public performance as a feminist act. In addition to their songs and stage performances, women in punk and the riot grrrl movement use zines to sound out an uncensored and distinctive voice, building support, creating networks, and sharing personal experiences. Strongly demonstrating their belief that the personal is political, their zines stand at the intersection of feminism, music, and DIY culture, exploring gender and sexuality, experiences of sexism and racism, struggles with eating disorders and body image, relationship problems, homelessness, abuse, disability, mental illness, and other forms of marginalization.

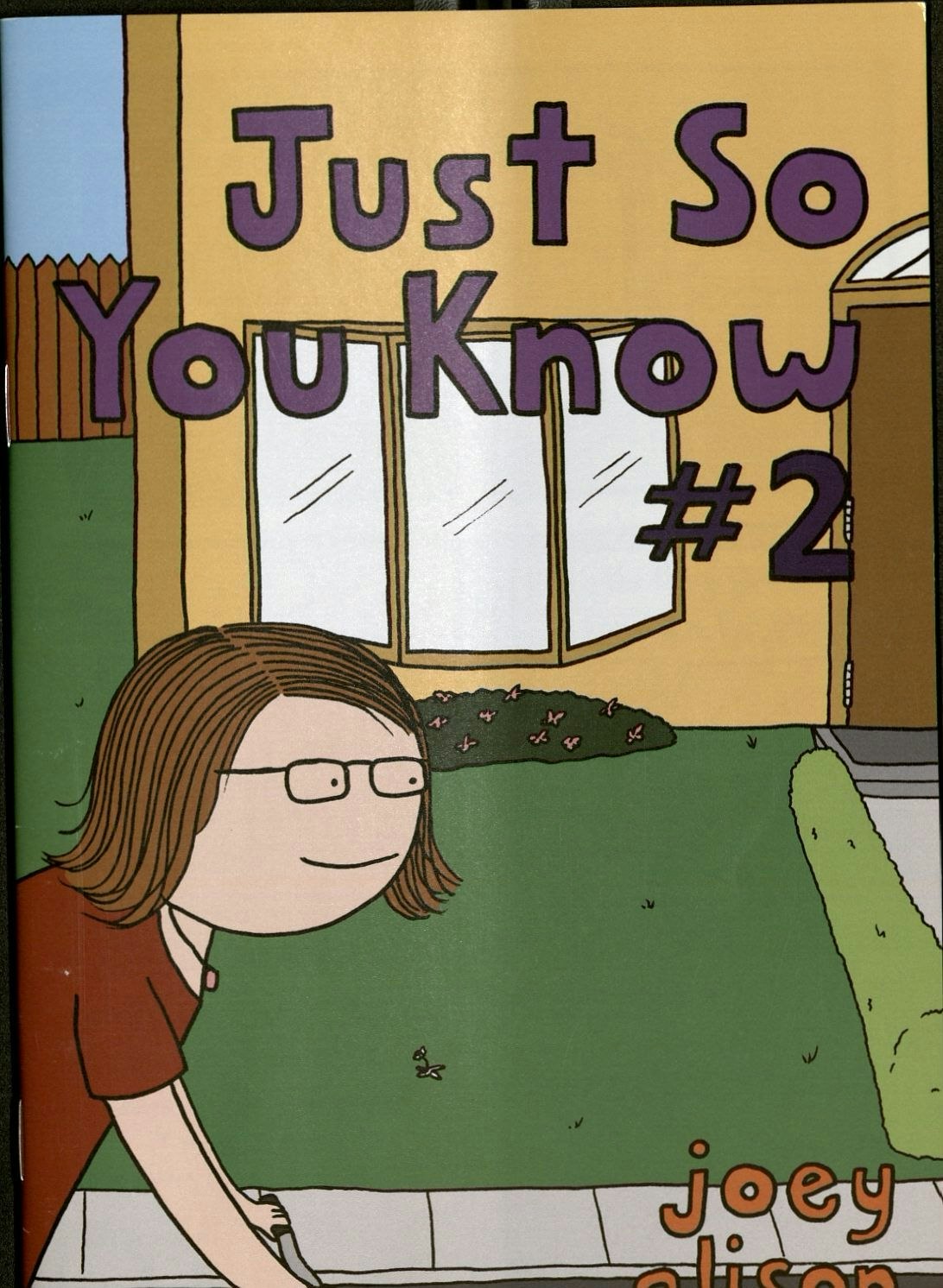

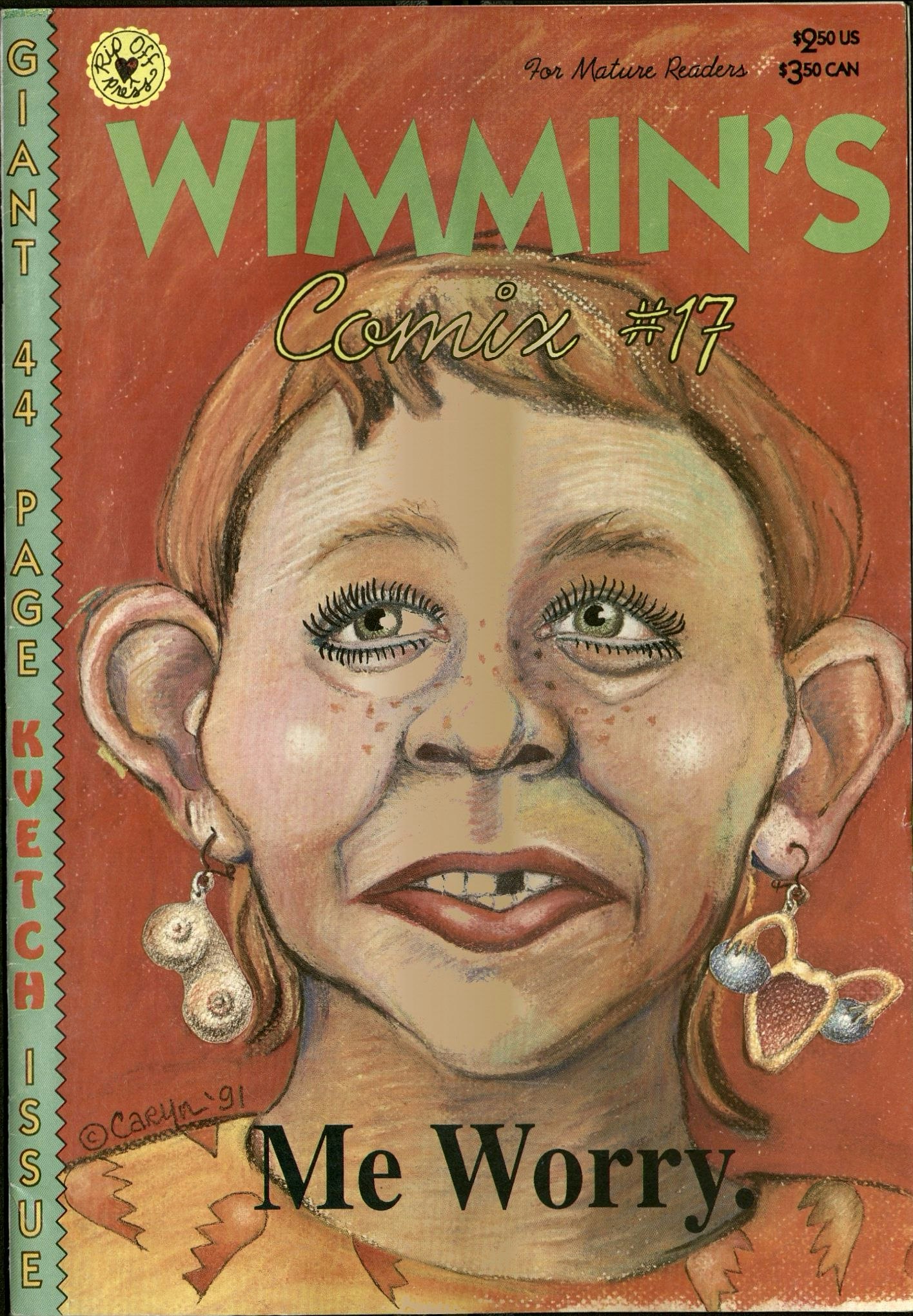

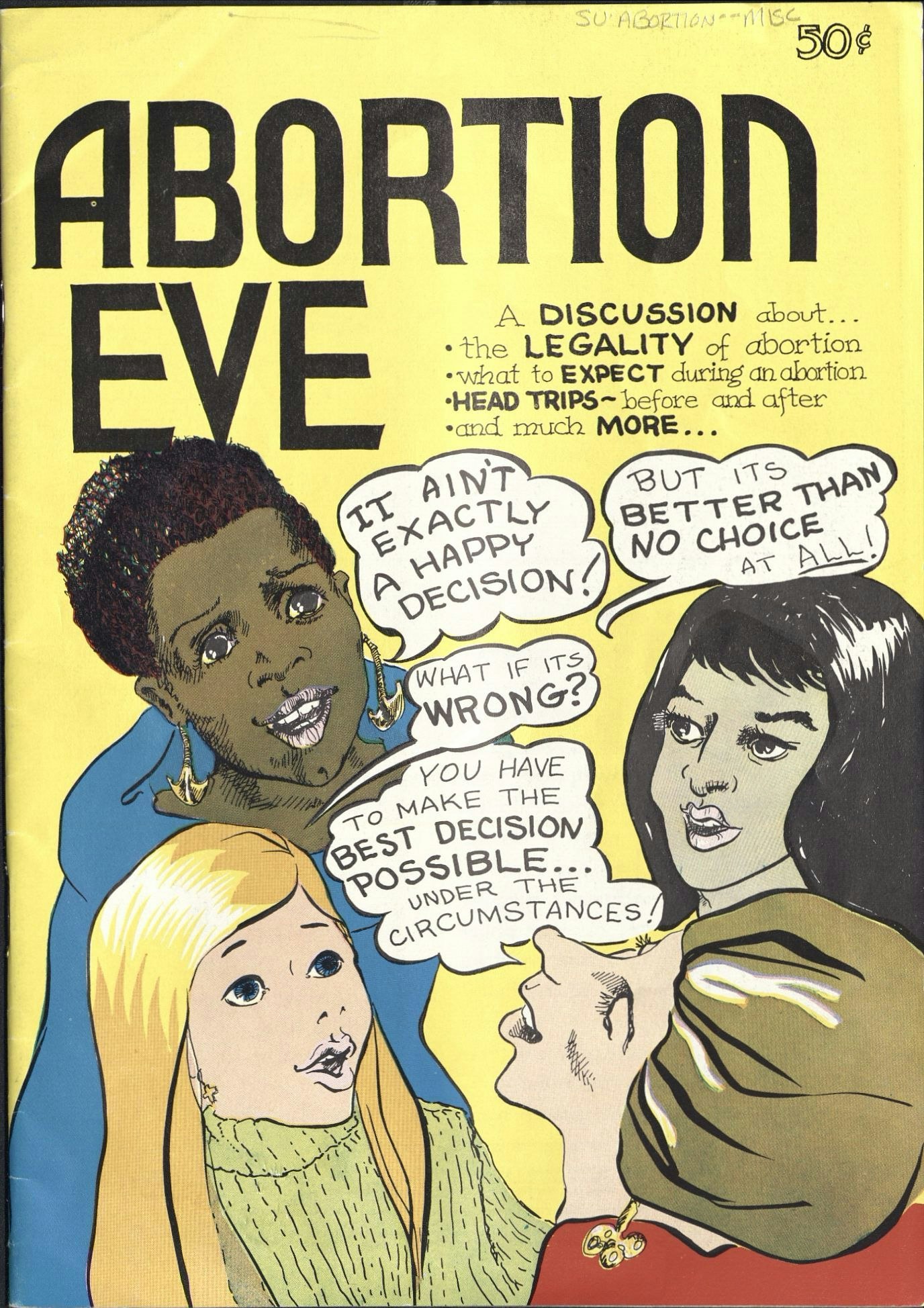

Comics

Comics drawn by women and aimed at women readers emerged in the late 1960s, as the consciousness raising of the women’s movement intersected with the often misogynistic male-dominated underground comix scene and the radical New Left more broadly. Trina Robbins’s cover for the groundbreaking 1970 anthology It Ain’t Me Babe featured a parade of angry cartoon females from comics’ “Golden Age” and quickly became an iconic image. Wimmen’s Comix, another collective enterprise including Robbins, appeared two years later, and many of its contributors went on to wide renown and are still active today. Their comics addressed a wide range of issues, including sexuality, gender, race, relationships, work life, health, abortion, and body image. A new generation of women comics artists, including Diane DiMassa and Alison Bechdel, appeared in the 1980s, and independent comics by women creators are still made today by artists such as Joey Alison Sayers.

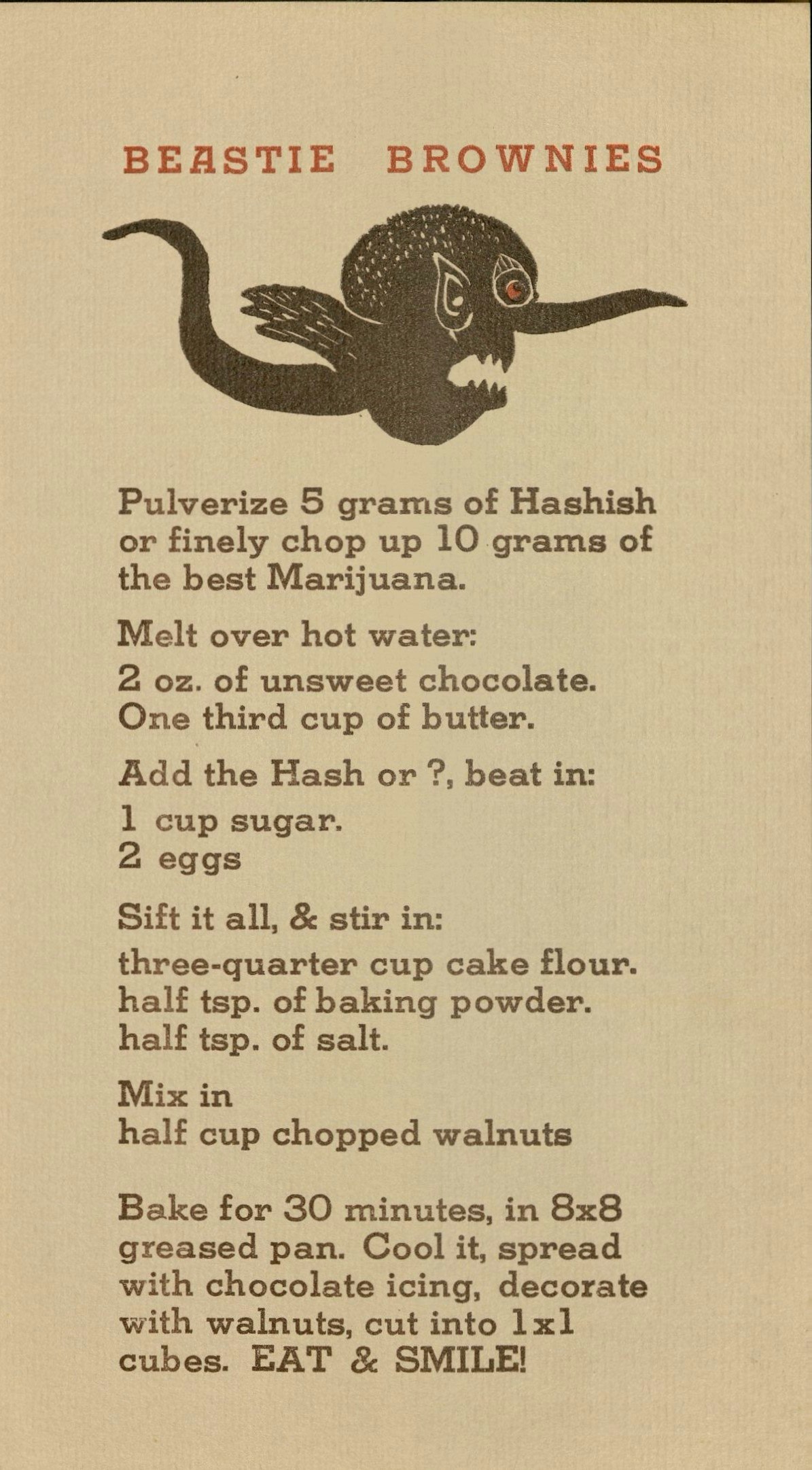

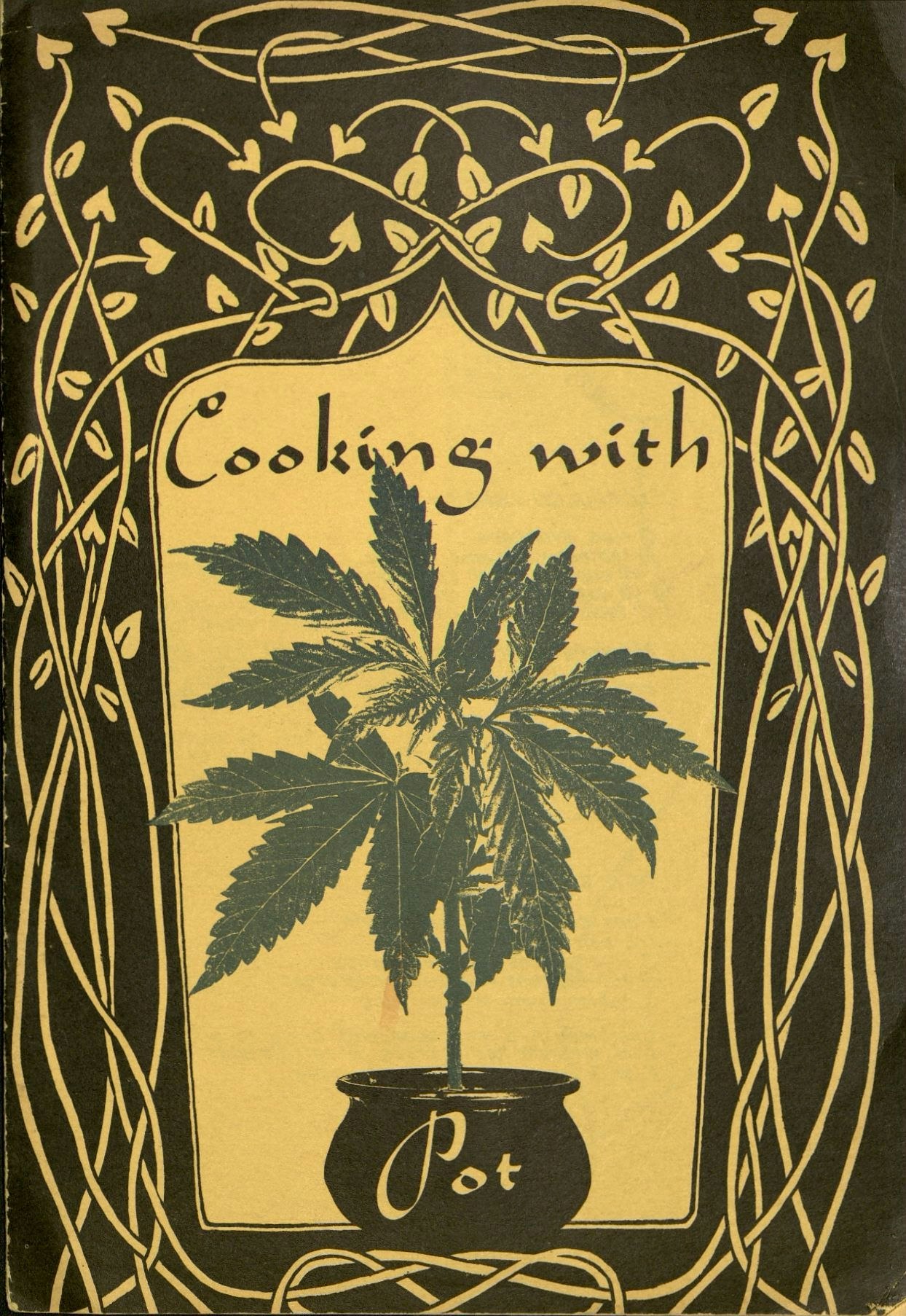

Cookbooks

The Schlesinger Library’s renowned culinary collection has long included books on cannabis cooking, and the collection has been enhanced by books from the Ludlow-Santo Domingo collection. Although the Haschish Fudge recipe from The Alice B. Toklas Cook Book (1954) is perhaps the best-known cannabis recipe, it was omitted from the first American editions. Hippie counterculture of the 1960s expanded the use of marijuana in cooking, with recipes for everything from soup to nuts; these cookbooks nearly always have at least one recipe for an infused butter or oil. Most of these cookbooks were published prior to the legalization of medical and recreational marijuana and usually contain disclaimers and warnings not to possess or consume the very ingredient they feature. Where cannabis is legal, new disclaimers are needed—edibles have always been notoriously difficult to dose, and today’s marijuana is much more potent.

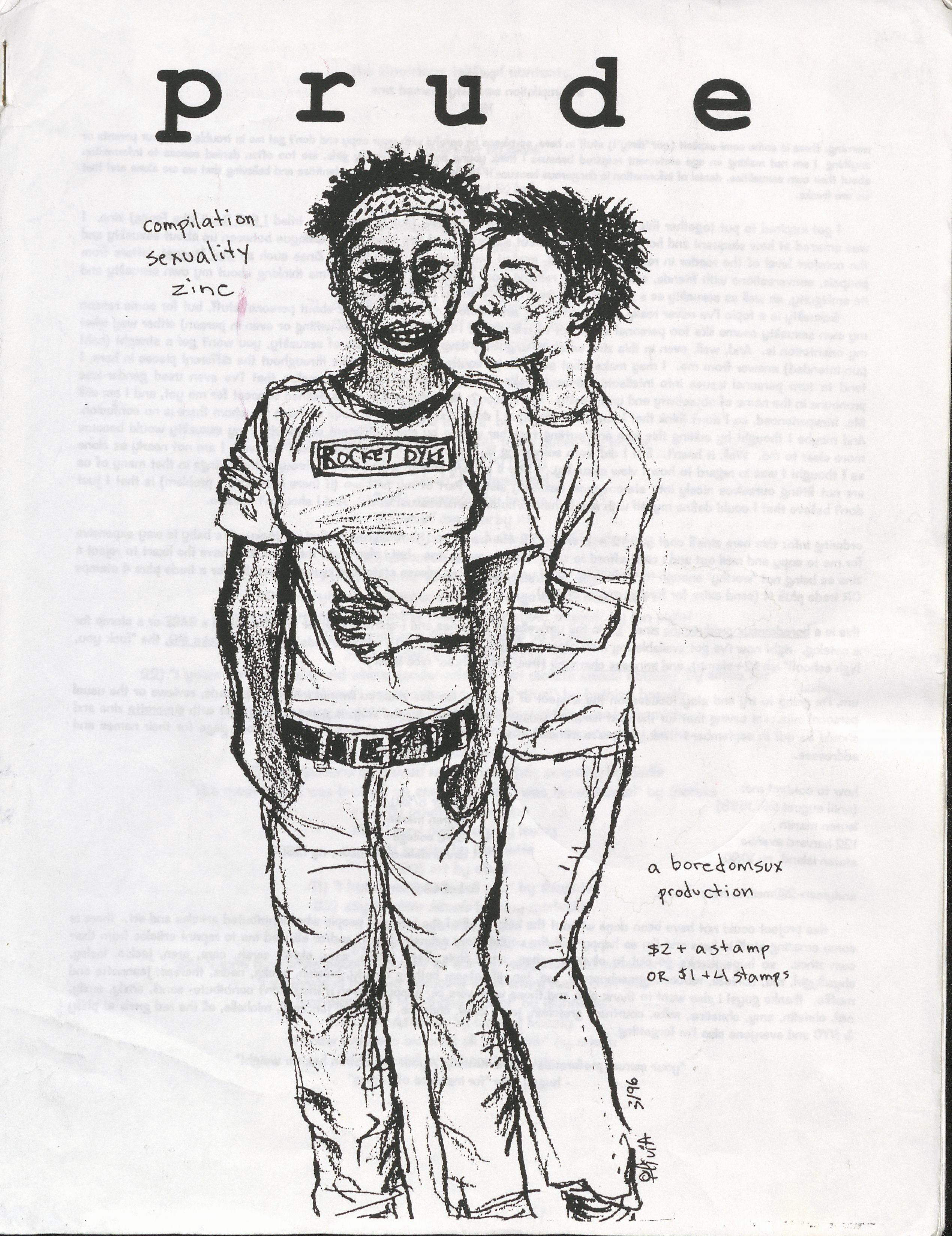

Zines

While today’s zine culture has developed out of fanzines and fandom, it is also heir to alternative self-published print culture more broadly, with links to chapbooks, pamphlets, and newsletters. Zines by girls and women not only discuss music and celebrity culture, but also feminism, reproductive health, and the personal lives of the authors. Zinesters write about parenthood, racial and gender identity, political action, bike riding, and cooking (vegetarian and vegan recipes being especially popular), using a variety of zine genres, including diary-like perzines (short for personal zines), minicomics, and artzines.

Zine History

Modern zine culture has roots in earlier fanzine (short for fan magazine) cultures, including science fiction and music fanzines. Heroine Addict, put out by The Comics Heroines Fan Club, was a long running fanzine devoted to comic-book heroines and featuring fan art, fanfic, and criticism. Fanzines like Aaron Elliot’s Cometbus, first published in 1981 and still being published, incorporated a punk rock strain of the do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos into fanzine production. The riot grrrl movement began to coalesce in the late 1980s and early 1990s as punk fanzines by women expanded the subject matter to include feminism, art, and personal narratives. Some zinesters, such as Darby Romeo, even made the leap to publishing more glossy publications—Ben is Dead had national distribution.

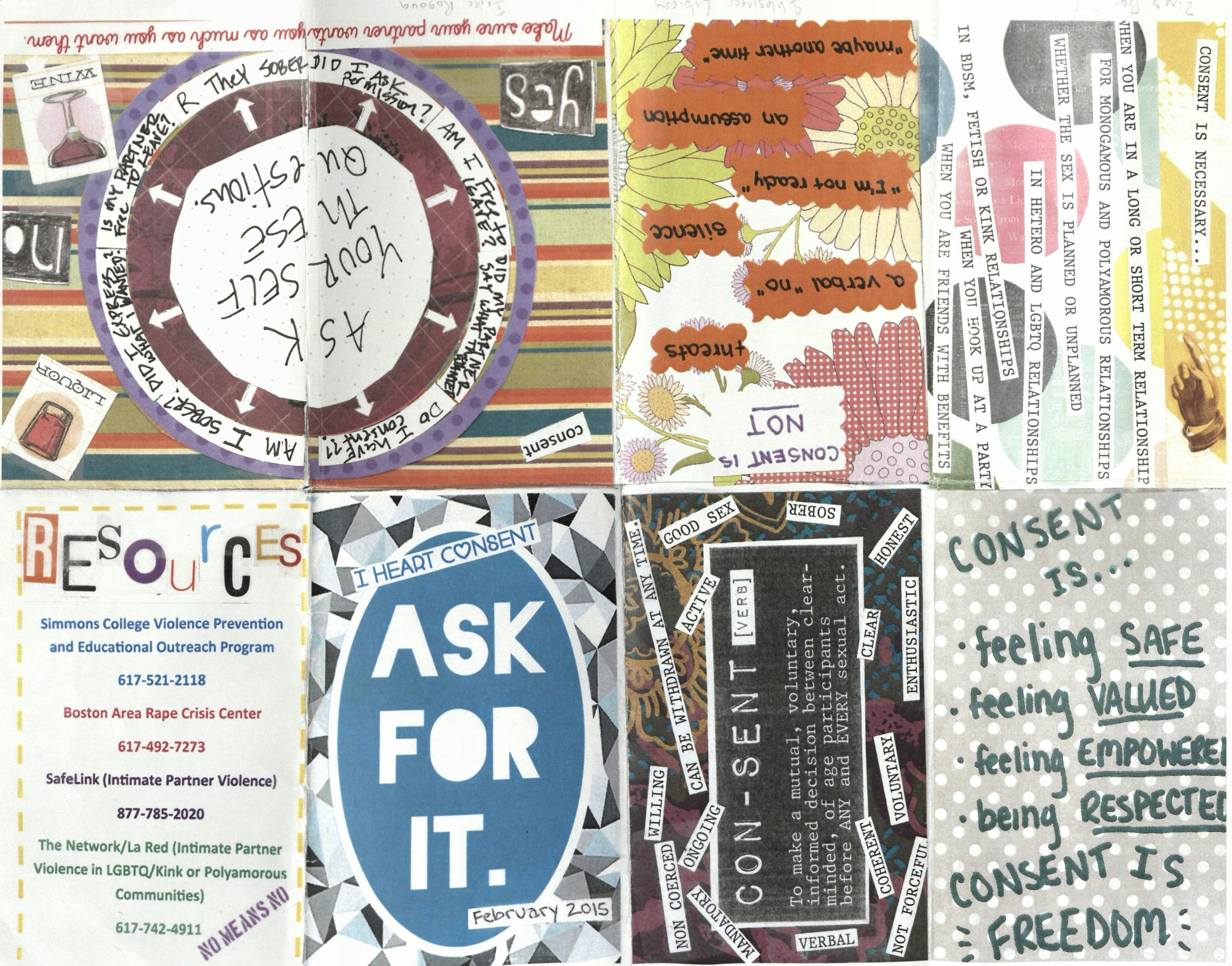

DIY Zines

An important subcategory of zines are DIY (do-it-yourself) zines, where zinesters promote and encourage the development of the DIY ethos in others. As self-produced and self-published works, zines embody DIY cultural production, and zinesters often engage in DIY practices beyond zine making. While DIY zines can be about pretty much anything, from beer making to home buying, many zines by women focus on DIY health and hygiene, as well as sexual assault prevention, support for survivors, and mechanisms for community-driven restorative justice. Other zines implicitly encourage a DIY approach to understanding and protecting oneself from dominant cultural narratives embedded in mainstream media, remixing commercial print culture to critique it and undermine its power.

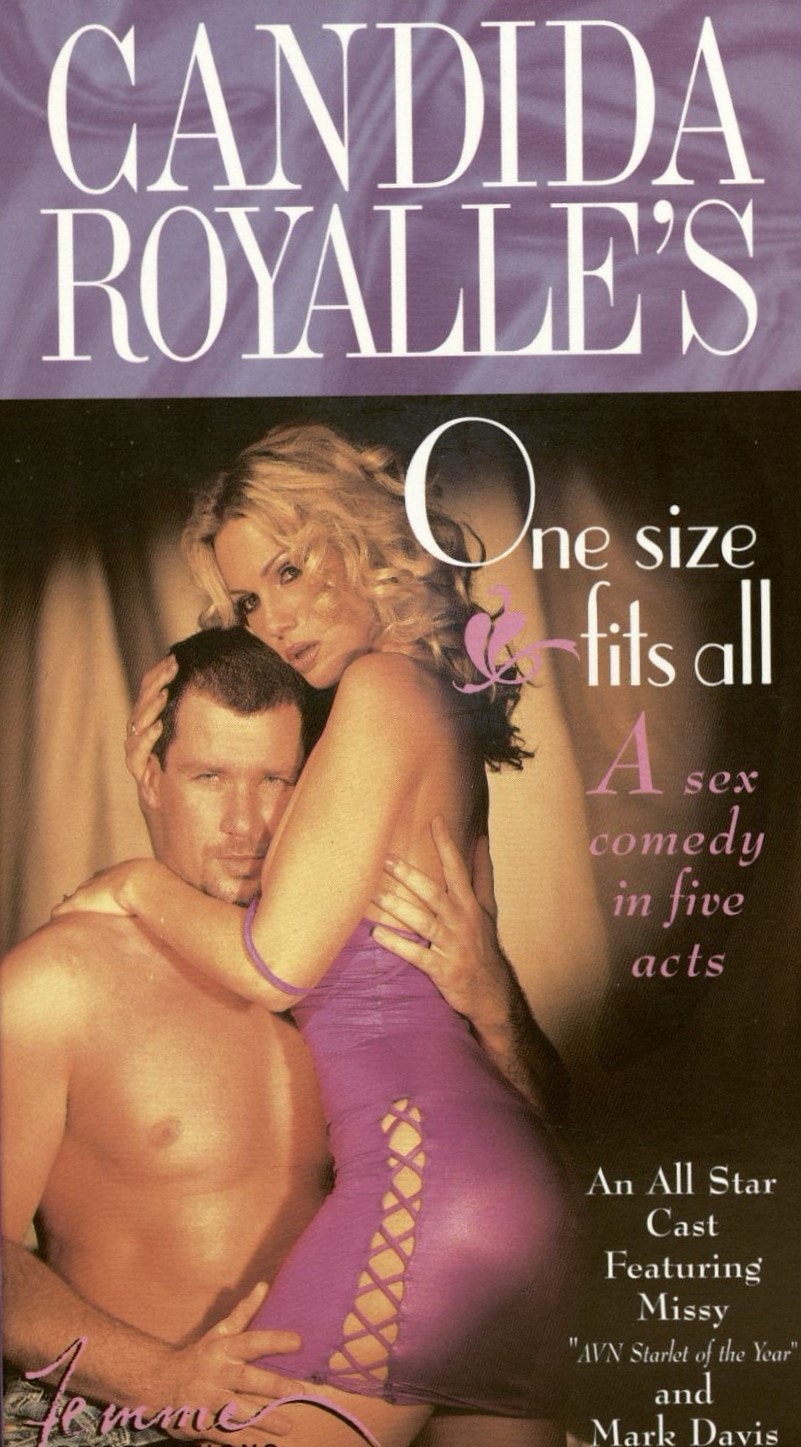

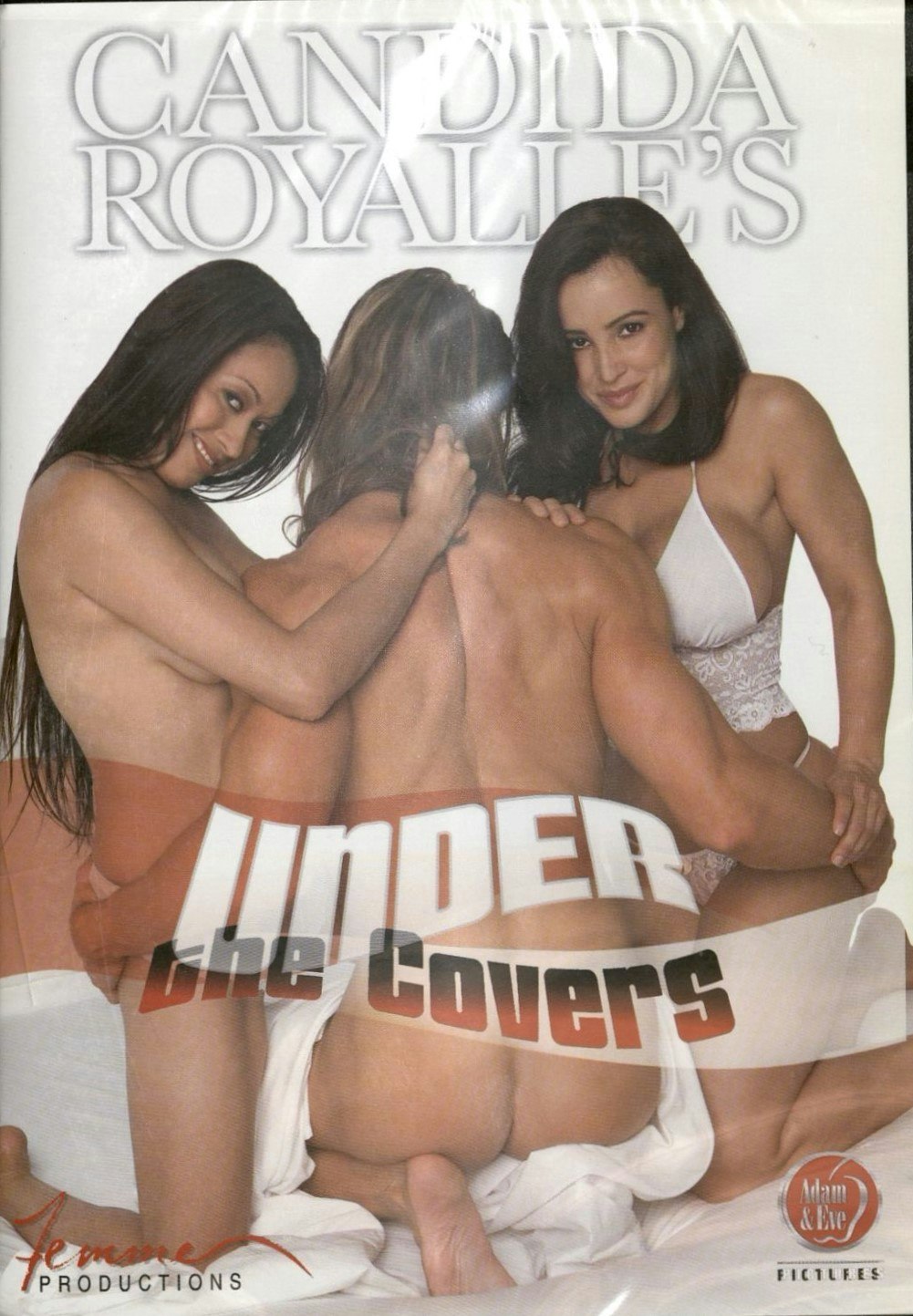

Candida Royalle

Materials from the Papers of Candida Royalle

A pornographic actress and producer and a director of erotica for women, Candida Royalle (1950–2015) founded Femme Productions with the goal of producing erotica based on female desire and also films for couples to enjoy together. Royalle advocated the use of safe-sex practices in her films, in contrast to much of the adult-entertainment industry. Royalle was a founder of Feminists for Free Expression, a sex-positive organization opposed to censorship. In 1983, she was also one of the founders, along with Veronica Hart, Gloria Leonard, Annie Sprinkle, and Veronica Vera, of Club 90, a support group for actresses in erotic films. In 1989, she signed the Post Porn Modernist Manifesto, a statement embracing sex positivism. A member of the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists, Royalle lectured widely at conferences and institutions, including the World Congress on Sexology and the Smithsonian Institution. She was the author of How to Tell a Naked Man What to Do: Sex Advice from a Woman Who Knows (2004).