The Age of Roe: Learn More about the Exhibition

Below you will find more information about select items in The Age of Roe exhibition. Please use the heading links to navigate to learn more.

Wall: The World That Made Roe

B.G. Jefferis and J.L. Nichols, Safe Counsel, Or, Practical Eugenics, Franklin Publishing Company, 1930. Schlesinger Library

Harry Hamilton Laughlin, Eugenical Sterilization in the United States, Psychopathic Laboratory of the Municipal Court of Chicago, 1922. Schlesinger Library

Eugenics, a theory that selective breeding could result in “racial improvement” among humans, was deeply entwined with questions about reproduction, parenting, race, class, and disability during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Eugenics enjoyed widespread support in the early twentieth century, with 32 states passing laws requiring the compulsory sterilization of people deemed to be “feebleminded” or “defective,” a group that included not only people with disabilities but also women believed to be promiscuous. Many early proponents of family planning and contraception, including the founder of Planned Parenthood, Margaret Sanger, held eugenic views regarding which women were most fit to raise children or strategically used then-popular eugenic arguments to advance their cause. In 1927 the United States Supreme Court, in Buck v. Bell, ruled that society had an interest in preventing "those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind." In the decades that followed, more than 60,000 people in the United States were forcibly sterilized.

These books on display show the broad public use of language around eugenics a century ago. Today, eugenics is known to be scientifically inaccurate and fueled by anti-immigrant sentiment, class bias, racism, ableism, and misogyny. A clear-headed examination of how power and bias have shaped American women’s access to reproductive care—and interacted with other movements around reproductive health—is necessary to understanding the realities of our current moment.

"Don’t Have An Abortion," by Jane Ward, 1941. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Mary Steichen Calderone

This article was originally published in American Mercury magazine in 1941, reprinted in the popular magazine Reader’s Digest, and further reprinted and distributed by Planned Parenthood. The author, Jane Ward, argued that abortion, at the time widely illegal, was too dangerous for women to make it worthwhile. She recounted her own illegal abortion and described “predatory professional abortionists” as interested only in money, not health care. Her suggested solutions were better birth control, and liberalizing laws against abortion so that more medical professionals could perform the procedure. These suggestions were in line with those advocated by Planned Parenthood and other reproductive-health advocates at mid-century.

Case: Abortion Activism in Massachusetts

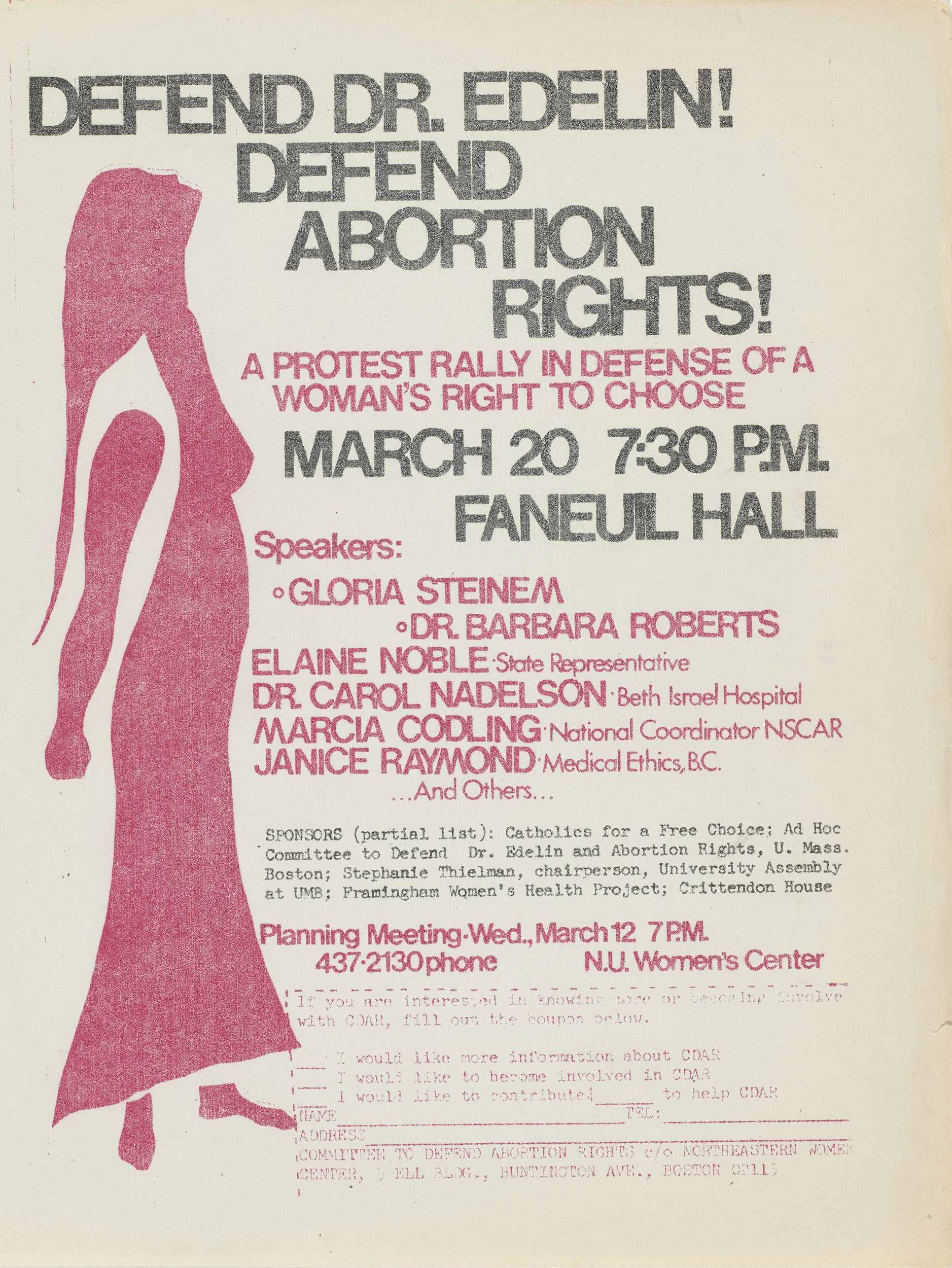

Committee to Defend Abortion Rights c/o Northeastern Women's Center, flyer, 1975. Schlesinger Library, Records of the Cambridge Women's Center.

Dr. Kenneth Edelin (1939-2013) was the first Black OBGYN chief resident at Boston City Hospital. In 1973 he performed an elective abortion for a 17- or 18-year old Black woman who Dr. Edelin estimated was at most 22 weeks along in her pregnancy. Roe v. Wade had just been decided, but a fellow resident was concerned about the gestational age of the fetus and questioned whether the procedure had in fact been legal. Prosecutors alleged that the fetus, whom they described as a baby, had been born alive and then killed by Dr. Edelin, and they charged him with a crime. In 1975, an all-white jury convicted Edelin of manslaughter. Edelin appealed, and the ruling was overturned by the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, which also held that medical professionals could not be prosecuted for certain abortions. Edelin’s case received a lot of press, and abortion rights advocates in Massachusetts and nationally seized on his prosecution and conviction to mobilize public support for abortion rights and the rights of medical providers. Pro-life groups also saw Edelin’s case as a milestone: a sign that their movement could argue that some abortions were illegal even if Roe v. Wade was the law.

Case: The Party Politics of Abortion

Ellen McCormack for President, postcard, 1976. Schlesinger Library, Joseph R. Stanton Pro-Life Collection

Ellen McCormack (1926–2011), a Democrat from New York, ran for president in 1976. One of her goals was to debate Jimmy Carter on the topic of abortion, forcing it to the party’s and the nation’s attention, and to obligate national television channels to air ads about abortion. McCormack was a pro-life activist who had had no experience in politics before this campaign. She raised more than $500,000 and was the first woman presidential candidate to be awarded matching federal funds and Secret Service protection. She ran for lieutenant governor of New York in 1978 and again for president, for the New York State Right to Life Party, in 1980.

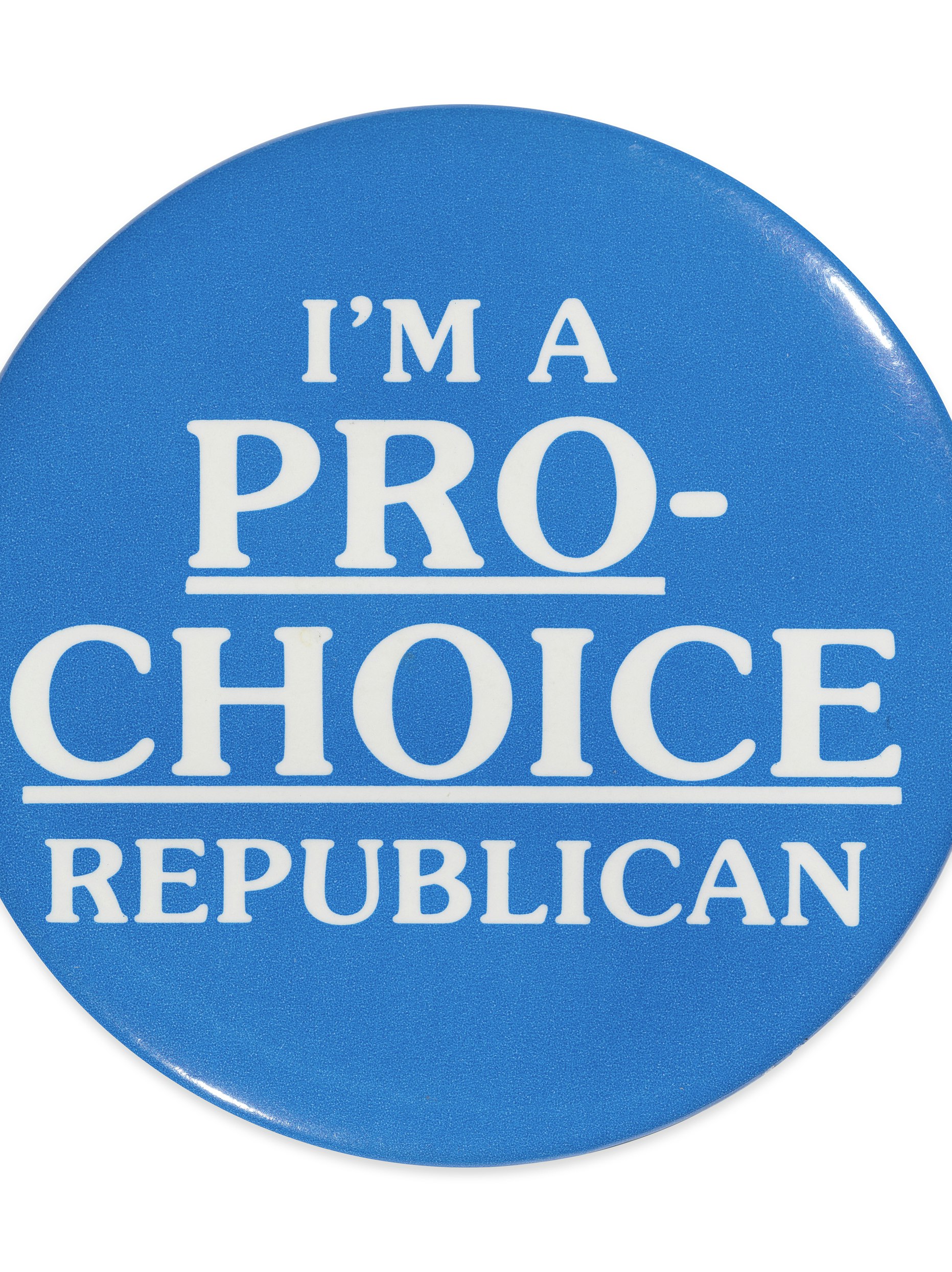

"I'm a Pro-Choice Republican," button, undated. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Mary Dent Crisp

Mary Dent Crisp. Chase Studios, Ltd., photographer, ca.1984. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Mary Dent Crisp

Mary Dent Crisp (1923-2007), a Republican Party member and activist from Arizona, was a supporter of abortion rights and the Equal Rights Amendment. She was an elected member of the Republican National Committee from 1976 to 1980. Throughout the 1970s, as opposition to her positions crystallized within the GOP, Crisp's outspoken defense of them became unwelcome. Ronald Reagan criticized her on television following the party’s convention in 1980. She continued to believe that party affiliation should not dictate one’s views on abortion rights and in 1990 she co-founded the National Republican Coalition for Choice.

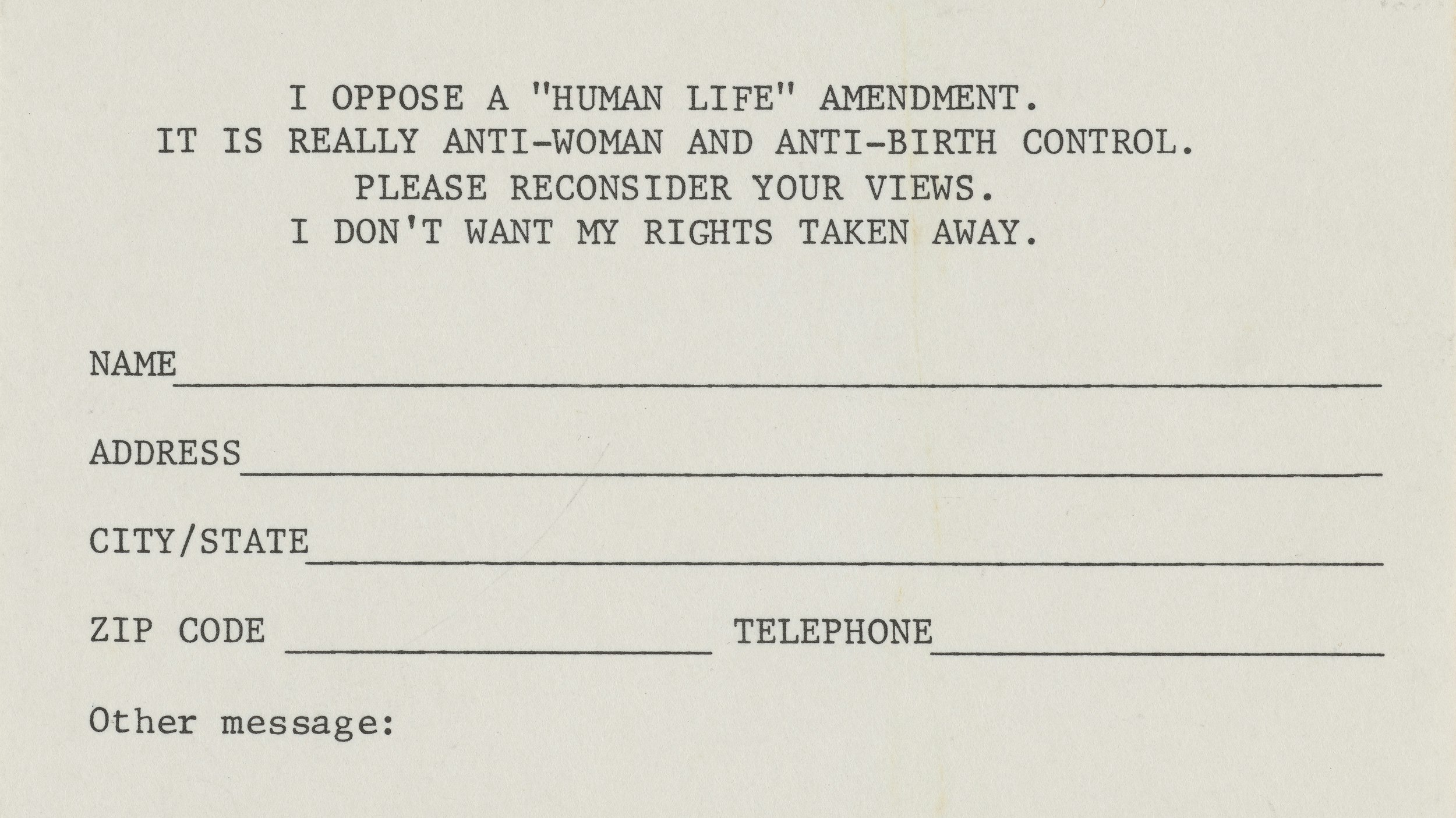

Opposition to Human Life Amendment, postcard, undated. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Bill Baird

Since 1973, more than 300 proposals to enact a Human Life Amendment to the United States Constitution have been brought before Congress. Most of them would define any human, from the moment of fertilization, as a rights-holding person entitled to equal protection and due process of law, and many made abortions performed by anyone unconstitutional. Others declared simply that there was no constitutional right to abortion. Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, the force behind several such “states’ rights amendments,” divided the pro-life movement, with some activists saying anything other than a constitutional abortion ban was not worth supporting. That divide notwithstanding, in 1983 a Hatch-Eagleton Human Life Amendment was formally voted on and narrowly defeated in the Senate. This postcard is most likely from that time period.

Hyde Amendment Kills Women, sticker, undated. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Susan B. Echo

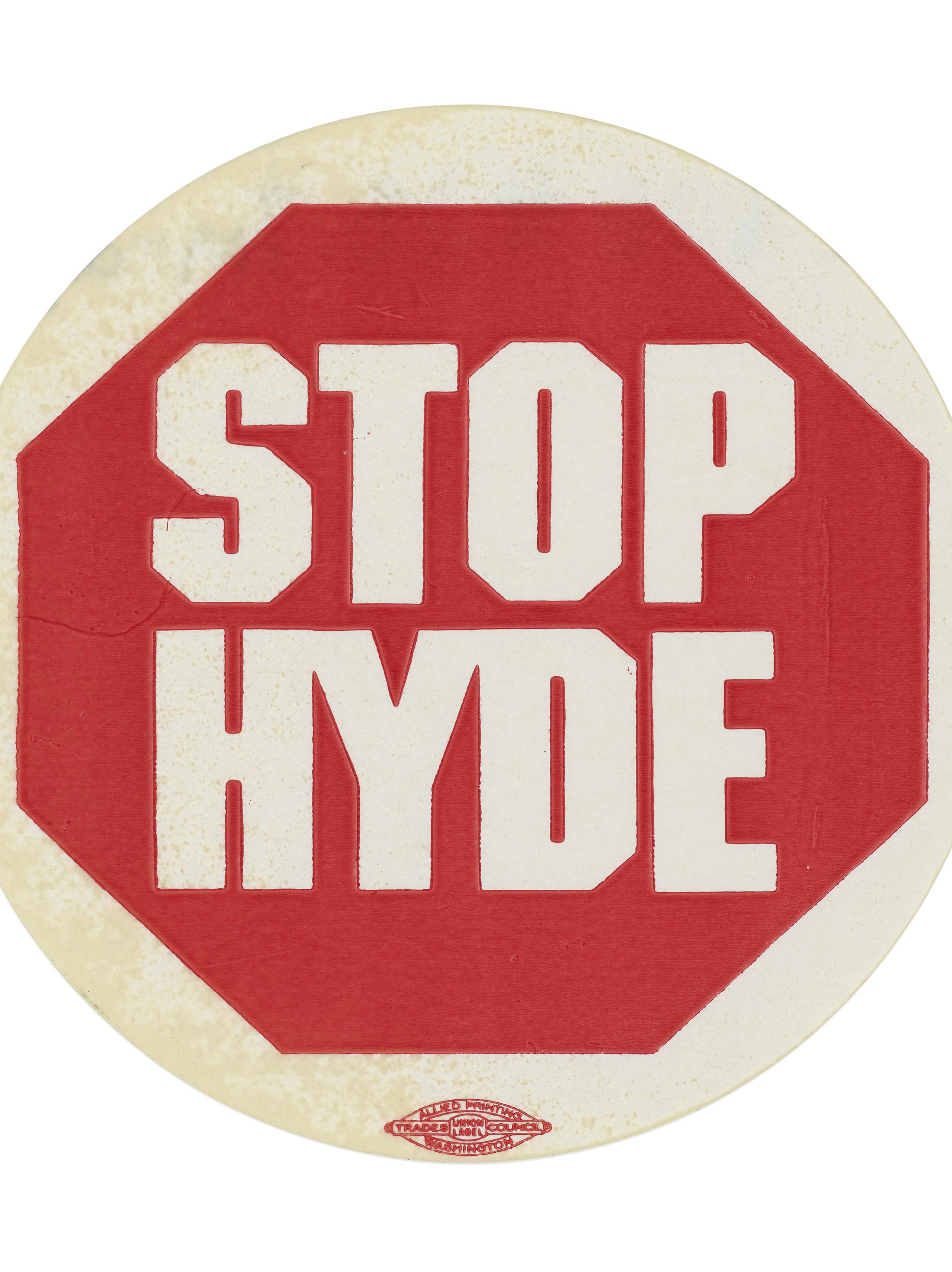

Stop Hyde, sticker, undated. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Susan B. Echo

Illinois Congressman Henry Hyde spearheaded an amendment to a government funding bill that prohibited federal funds from paying for abortion care. When the Hyde Amendment passed Congress, in 1977, it cut off affordable abortion access for millions of women who received health care through Medicaid, the government-funded program for low-income people. Other groups affected were Native American women, women in the military and veterans, residents of Washington, D.C., federal government employees, and women in federal prisons or detention facilities.

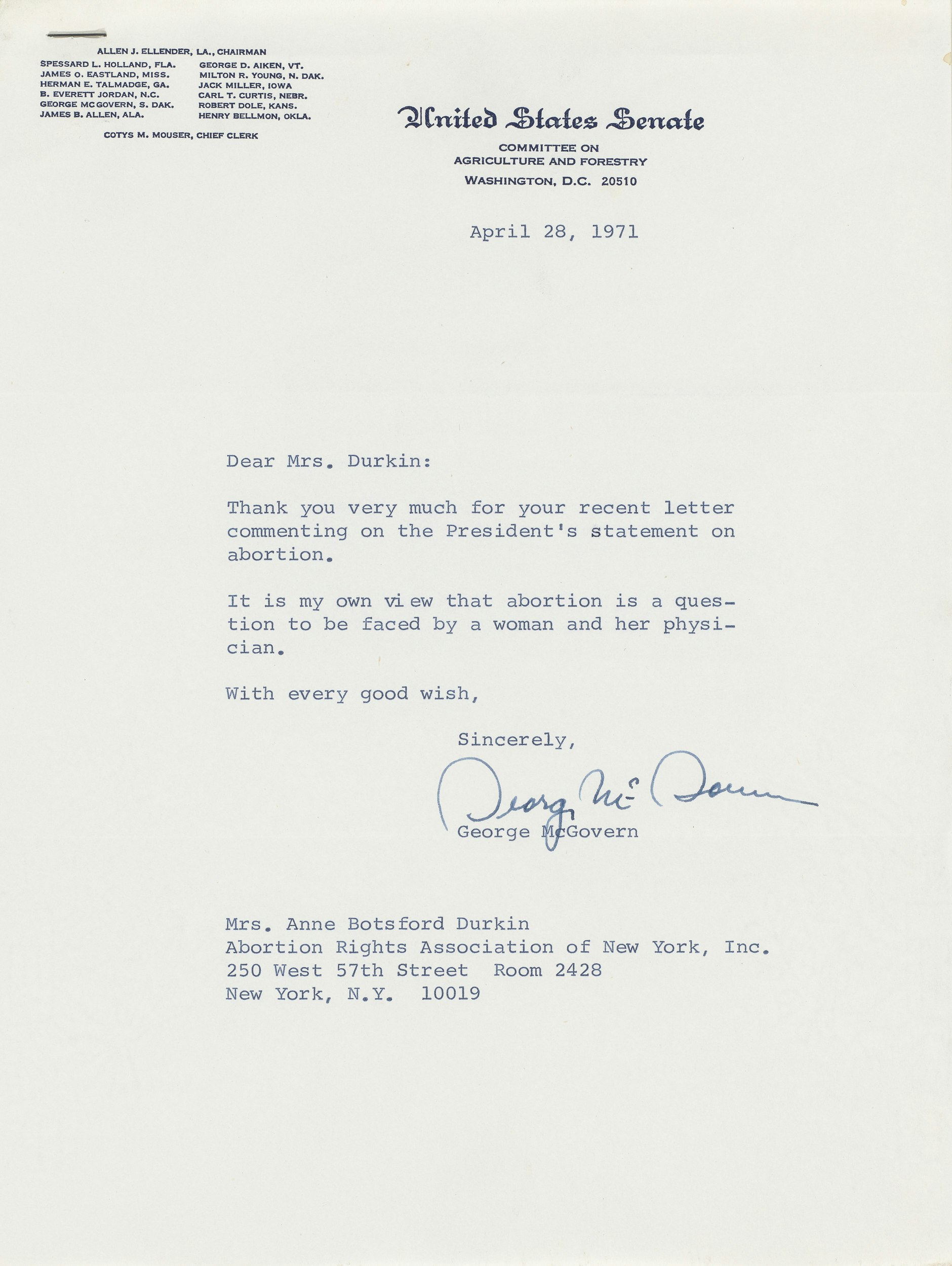

Senator George McGovern to Anne Botsford Durkin, Abortion Rights Association of New York, letter, April 28, 1971. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Ruth Proskauer Smith

On April 4, 1971, President Richard Nixon announced that abortion policies on military bases, which are under federal control, would follow the laws of the surrounding state. A uniform policy more protective of abortion rights had been put in place the previous summer for abortions at military hospitals. Nixon also used this occasion to announce his personal opposition to abortion.

In this letter, South Dakota Senator George McGovern is responding to Anne Durkin, the executive secretary of the Abortion Rights Association of New York, who had written to him expressing pro-choice activists’ outrage at President Nixon. Durkin wrote, “[I]t is obvious that the President made a political blunder by making such a statement based on his religious beliefs. Judging from the outraged response which his statement is eliciting from the many groups active in abortion reform here and all over the country, I have no doubt that this statement has elevated the issue of abortion to one of major significance in the next election. We hope that you will take a more informed position on this issue and that you will share your views on it with us.”

George McGovern challenged President Nixon in the 1972 presidential race. He once expressed some support for abortion reform but retreated from his earlier position during the 1972 campaign for fear of alienating Catholic voters. Nixon attacked him for his earlier support of abortion rights, famously lambasting McGovern for supporting the “3As”: acid, amnesty for those seeking to avoid the draft, and abortion. Nixon won in a landslide.

Case: Faiths, Lives, Choices

Manning M. Lee to Norma McCorvey, letter, August 11, 1995. Schlesinger Library, Joshua Prager Collection on Norma McCorvey and Roe v. Wade.

Norma McCorvey (1947-2017) was the anonymous plaintiff “Jane Roe” in the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade. Her inability to obtain an abortion under Texas law was at the center of that case. McCorvey gave birth to her third child, known as the “Roe baby,” before her case reached the Supreme Court. McCorvey went public with her identity in the mid-1980s and became a speaker for abortion rights. In 1995 she was baptized by Philip “Flip” Benham, an evangelical minister and the director of Operation Rescue, a pro-life group focused on direct, sometimes violent action at abortion clinics. McCorvey then joined the pro-life movement and co-founded the pro-life organizations Roe No More Ministry and Operation Outcry. McCorvey’s own views on abortion—that the procedure should be legal, but only for the first twelve weeks of pregnancy—did not fit well within either the pro-choice or the pro-life movement.

Case: Race and Abortion

Combahee River Collective Press Statement, September 6, 1976. Schlesinger Library, Records of the Cambridge Women's Center

The Doyle-Flynn bill referenced in this flyer cut all state funding for abortion. Massachusetts State Representatives Charles Doyle and Ray Flynn, inspired by the federal Hyde Amendment, introduced their bill in the Massachusetts legislature in September 1977. The Doyle-Flynn bill was passed in July 1978, but a lawsuit filed by the pro-choice group MORAL successfully secured a temporary injunction in September 1978. Governor Dukakis vetoed the bill twice, but the legislature voted to override that veto.

The Combahee River Collective, a Black feminist organization founded in Boston in 1974, positioned abortion funding as a key issue of justice, related to protection from forced sterilization, access to health care for people of color, and safety from domestic violence and sexual assault. The organization’s statement makes clear the importance of coalition work for activists.

Liberator, August 1970. Schlesinger Library, Records of the Cambridge Women's Center

Liberator (1960-1971) was a monthly magazine that helped shape Black intellectual thought and activism. Christy Ashe’s article “Abortion...or Genocide?” is a radical critique of abortion rights as a means of reproductive freedom, part of a larger discourse among some Black activists, including Jesse Jackson, who then tied the legalization of abortion to racism, eugenics, or an unwillingness to help marginalized communities. Ashe argues that liberalizing abortion policy in New York State will benefit “the nice, well-speaking, ‘educated’ white girl” and will cause wider issues, such as housing, education, schooling, pollution, and general welfare, which primarily affect Black and brown populations, to be of less importance. Ashe further suggests that abortion will be used as a population-control measure, and ends by saying that the new laws must be serving an ulterior purpose, as “women don’t get what men, public and private, don’t want, whether it’s babies, abortions or the basics to survive. Anyone who followed the [New York abortion law] campaign in press, media, and magazine has to be aware of who really wants it, who desperately needs this latest quickie solution to addiction, pollution, noneducation, inflation, medical malevolence, housing, unemployment, and the farm subsidy program.”

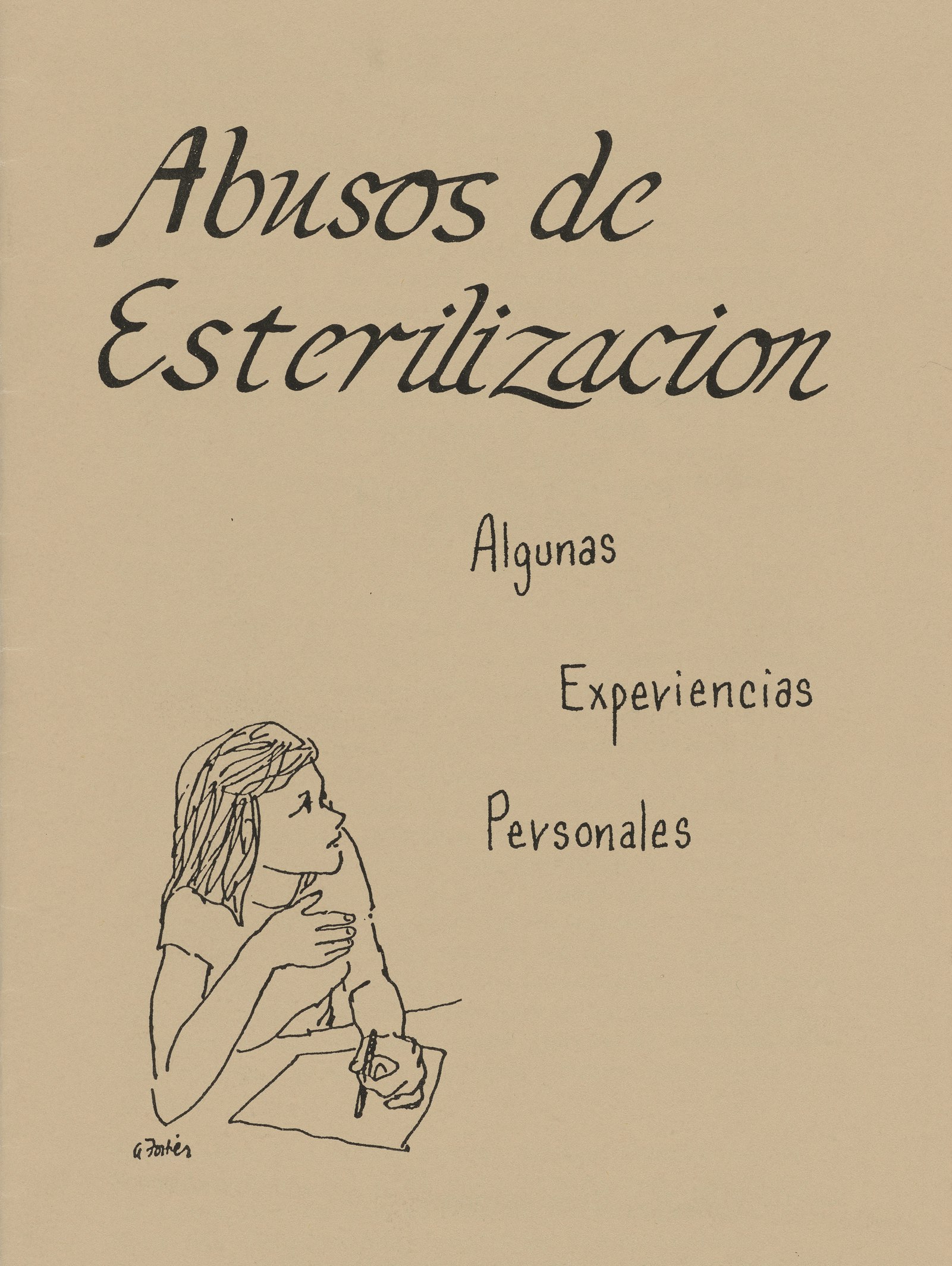

Sterilization Abuse: Some Personal Experiences, compiled by the Ad Hoc Committee on Sterilization, San Francisco, California, booklet, ca.1977. Schlesinger Library

The United States has a long history of forced-sterilization campaigns against people of color, low-income Americans, and persons with disabilities. Unlike an individual’s decision to terminate a pregnancy, sterilization was state-sponsored reproductive control. While the eugenics movement lost favor after World War II, as many drew parallels to the sterilization program of Nazi Germany, forced sterilizations continued. In parts of the American South, they increased, often targeting people of color: From 1950 to 1952, North Carolina sterilized the largest number of people in the history of its eugenic law, the vast majority of them women of color.

By the 1960s and 1970s, so-called Mississippi appendectomies, a term used for forced sterilizations, had become an open secret. In 1973, two Black sisters, Minnie and Mary Relf, were involuntarily sterilized; their mother, who was unable to read, believed they were receiving hormonal contraception. With the assistance of the Southern Poverty Law Center, the Relfs brought a class action lawsuit, drawing attention to the issue of forced sterilization and the many forms it took, from patients’ receiving misinformation to others’ being threatened with the loss of welfare benefits or custody of their children.

This bilingual booklet, part of a Sterilization Abuse and Informed Consent Project, focuses primarily on a clinic at San Francisco General Hospital that provided free sterilization. It includes testimonies by doctors and residents, nurses, and patients about a lack of informed consent for patients. The booklet is also indicative of the 1970s feminist health movement, which aimed to give patients enough information to make informed decisions about their own health care.

Wall: Cross of Oppression

Bill Baird (at right) holding the Cross of Oppression with Father Frank Pavone (at left) and an unidentified woman, National Right to Life Convention, 2003. Schlesinger Library, Papers of Bill Baird

The birth control and abortion activist Bill Baird had this cross built in 1982 and subsequently carried it at many protest marches for abortion rights.

Baird (born 1932) worked as the clinical director for a drug company that manufactured contraceptive foam. He became an outspoken advocate for the use of contraception, and his public distribution of a condom and contraceptive foam to a Boston University student in 1967 spurred a legal fight that resulted in the 1972 Supreme Court decision Eisenstadt v. Baird, which struck down a Massachusetts contraception law and recognized a right for individuals to use contraception. Baird ran several women’s health clinics in Boston and in Hempstead, New York, which provided birth control, abortion, and related services. After Baird’s Hempstead clinic was firebombed, in 1979, he began to engage directly with pro-life activists to encourage dialogue and to stop violent encounters at clinics.

Wall: Abortion and Justice

"Prisoner of War," wall calendar for Joan Andrews, ca.1987. Schlesinger Library, Joseph R. Stanton Pro-Life Collection

The pro-life activist Joan Andrews has been protesting at abortion clinics for decades, often physically blocking clinic entrances with her body, and has been arrested more than 100 times. In 1986, Andrews was arrested following an anti-abortion sit-in at The Ladies’ Center, a women’s health clinic that provided abortions, in Pensacola, Florida. She was charged with burglary, criminal mischief, and resisting arrest without violence after attempting to unplug medical equipment used inside the clinic. Many in the pro-life movement found her conviction and multi-year prison term excessive, and referred to her as a political prisoner unfairly jailed for actions based on her beliefs. This framing of the conflict over abortion as a war, in which arrested protesters are characterized as martyrs to a righteous cause, shows the strong conviction that many pro-life activists bring to the cause. Andrews and others like her became heroes not only to nonviolent protestors but also to a handful of activists who violently attacked clinics and those who worked inside them.

Reading List

The Age of Roe explores the complex history that produced and followed the Roe decision. This short reading list provides a helpful starting point for those interested in learning more about this consequential period in our history.

- Donald Critchlow, Intended Consequences: Birth Control, Abortion, and the Federal Government in Modern America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999)

- Sara Dubow, Ourselves Unborn: A History of the Fetus in Modern America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010)

- John Finnis, “Abortion Is Unconstitutional,” First Things, April 2021

- David Garrow, Liberty and Sexuality: The Right to Privacy and the Making of Roe v. Wade (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998)

- Mary Ann Glendon, Abortion and Divorce in Western Law (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987)

- Michele Goodwin, Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020)

- Jennifer Holland, Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2020)

- Felicia Kornbluh, A Woman’s Life Is a Human Life: My Mother, Our Neighbor, and the Journey from Reproductive Rights to Reproductive Justice (New York: Grove Atlantic, forthcoming 2023)

- Andrew Lewis, The Rights Turn in Conservative Christian Politics: How Abortion Transformed the Culture Wars (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017)

- Kristin Luker, Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984)

- Melissa Murray, “Race-ing Roe: Reproductive Justice, Racial Justice, and the Battle for Roe v. Wade,” Harvard Law Review 134 (2021): 2025–2102

- Joshua Prager, The Family Roe: An American Story (New York: W.W. Norton, 2021)

- Leslie Reagan, When Abortion Was a Crime: Women, Medicine, and the Law in the United States, 1967–1973 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997)

- Loretta Ross and Rickie Solinger, Reproductive Justice: An Introduction (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017)

- Johanna Schoen, Abortion after Roe (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

- Before Roe v. Wade: Voices That Shaped the Abortion Debate Before the Supreme Court Ruling, ed. Reva B. Siegel and Linda Greenhouse (New York: Kaplan, 2010)

- Daniel K. Williams, Defenders of the Unborn: The Pro-Life Movement Before Roe v. Wade (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016)

- Joshua C. Wilson, The Street Politics of Abortion: Speech, Violence, and America’s Culture Wars (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2013)

- Mary Ziegler, Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022)