A Rare Sisterhood

A Fictionalized Medieval Abbess Might Not Exist but for Real-Life Fellowship

What’s left of Marie de France are poems—12 of them—that describe subjects unusual for a 12th-century abbess: adultery, love, interactions between men and women of different classes. Poems that indicate a life beyond the cloister.

In Matrix (Riverhead Books, September 2021), the novelist Lauren Groff RI ’19 takes what little is known of the author of these poems and weaves them into an exploration of abbey life in medieval France. Groff’s reimagined Marie is the half-sister of Eleanor of Aquitaine. The fact that she came from a rape haunts her throughout her life. Sent to a poor abbey because of her low status, Marie enters a world only of women, to whom she becomes a friend, sometimes lover, sometimes enemy, and eventually prioress and abbess. She comes to cherish this group, “for this community is precious, there is a place here even for the maddest, for the discarded, for the difficult, in this enclosure there is love enough here even for the most unlovable of women.”

When Marie arrives at the abbey, it is isolated and abject. Through her cunning, it becomes rich; so much so that the crown becomes jealous of her success. As abbess, she closes the land off from its surroundings by banishing all male servants and later builds a labyrinth on the property. She hopes that “her daughters would be removed, enclosed, safe. They would be self-sufficient, entire unto themselves. An island of women.”

One lovely thing about the book is how it moves like a labyrinth, following Marie’s story from childhood to death but sometimes allowing itself to get lost in her visions, her writing, and the lives of her sisters in the priory. One “has the affronted air of someone who lurks in corners to hear herself spoken ill of so that she can hold tight a grievance to suckle.” Another, a mad nun, “goes into the sheepfolds dancing and is struck dead by lightning, a small and perfect black hole running into her skull and out her left heel.” These sisters frustrate, seduce, and sometimes annoy Marie, but she sees them as her own: “All holy sisters at Marie’s abbey are treasured as pearls.”

Groff’s book has a particular Radcliffe backstory: she was working on a different manuscript as a fellow when she heard a talk by Katie Bugyis, a historian in her cohort. She set down that project and started another. The result is a paean not only to sisterhood but also to the idea and ideal of collectivity.

All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake (Random House, 2021), by Tiya Miles ’92, RI ’22

It is just over two feet long and a foot wide, made of cotton and thread, and embroidered with the following words:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

This object, a bag known as “Ashley’s Sack” is the center of Tiya Miles’s extraordinary and moving book. From its 10 lines, Miles re-creates the lives of men and women whose existence was previously reduced to whether they were bought and sold.

Miles looks for Rose and Ashley, the two women mentioned on the bag, among the records of enslaved people in Charleston, a city built “on the foundation of slave-grown rice.” It is “a madness,” she writes, “if not an irony, that unlocking the history of unfree people depends on the materials of their legal owners, who held the lion’s share of visibility in their time and ours.” The only mention of a person’s life might be the record of their sale. An Ashley and a Rose appear on the property of Robert Martin, who owned an estate in Charleston. The only indication of their age is their price in the estate inventory. Ashley’s worth was set at $300, suggesting she may have been “a younger or relatively unskilled worker.” Rose, at $700, “must have been in the prime age of her life.” She may, Miles notes, “have been priced at this amount because of her sexual appeal to white men.” These three digits provide a painful glimpse into Rose’s life.

Miles documents the meaning of the objects in the bag, from hair, a symbolic way to connect Ashley to her family and heritage, to the “tattered dress” by which a mother might have expressed her wish to see her daughter secure and dignified. Pecans had their own meaning: a delicacy that almost no enslaved person would have been able to access. Each of these objects is a metonymy for a world for which few records exist. Miles brings in other voices when we are unable to access Rose’s and Ashley’s own.

The sack that Rose packed for her daughter is a rare object. But all “slave mothers lived in a shadowland of constant, scathingly rational fear,” Miles writes. She describes the actions of women who knew their children would be sold and their desperation to be reunited. In one letter, from 1857, a woman named Vilet sold away from her daughter asked her former owner for information about “what has Ever become of my Presus little girl. ... I do wish to see her very much.” Miles notes, “The archive contains no indication of how this story ends.”

Did Rose always know that her daughter would be sold? Miles asks. “We must presume that Rose always knew that she would birth a motherless child. For this was the root of slavery: theft of the maternal.”

All That She Carried won the 2021 National Book Award for nonfiction.

The Church of the Dead: The Epidemic of 1576 and the Birth of Christianity in the Americas (NYU Press, August 2021), by Jennifer Scheper Hughes MDV ’96, RI ’17

Anyone who has survived the past year knows that the reach of epidemics goes far beyond health. In The Church of the Dead, the historian Jennifer Scheper Hughes argues that epidemics can result in new religious feeling. She looks at the waves of plague that shaped Mexico in the 16th century, called the mortandad. These pandemics, she writes, left millions dead and a new colonial church suffering to assert itself. “The fact of mass death shaped all dimensions of the emerging colony, defining religious institutions perhaps most of all—as this was where meaning, identity, self, and society were made.”

The Mexican epidemics were frightening and deadly. As one Nahua commentator described of a plague called cocoliztli, which emerged in April 1576, “In two or three days [those affected] died of hemorrhage, blood emerged from their noses, from the ears, from the eyes, from the anus. And women bled between their legs. And for us men, blood emerged from our members. Others died from diarrhea, which took them suddenly, they died quickly from this.” This death particularly affected Indigenous populations, and one contemporary commentator, a Mexican-born Dominican missionary, noted that they might be totally eradicated. “After so many ages the Indios will come to their end so completely that those who arrive in this land [in the future] will ask what color they had been.”

Hughes looks at writing from missionaries and contemporary Indigenous commentators to understand how the epidemic shaped both religious practice and feeling. Where the history of Christianity in Mexico has long been understood as the result of missionary work, she shows how the church survived in spite of proselytizers. Instead, Indigenous Christians asserted themselves through the new church, shaping it around their own ideals.

Missionaries built hospitals during the plague, Hughes writes. But they used this fact to show their own superiority. “If the Spanish seemed relatively immune to the disease—only a small handful of Spanish religious died from cocoliztli and were therefore considered martyrs—that was the case because God spared them so they could care for the afflicted,” writes Hughes of the way these men saw their work. Indeed, one contemporary Franciscan theologian noted that the missionaries’ self-confidence was often misplaced. “Some grew tired and others fell ill themselves, and still others needed to return to their haciendas, and now many of the said priests who were helping no longer help.” Among the documents Hughes presents here are letters from Spanish missionaries begging to be relieved of their duties and sent back home.

Hughes seeks to understand how Indigenous Christians shaped the theology of their church. To her, their faith ensured not only the survival of Christianity in Mexico but also its transformation. “In summary, the Mexican church endured the mortandad because communities of Indigenous Christians asserted a rival theological and institutional scaffolding that carried it into the future.”

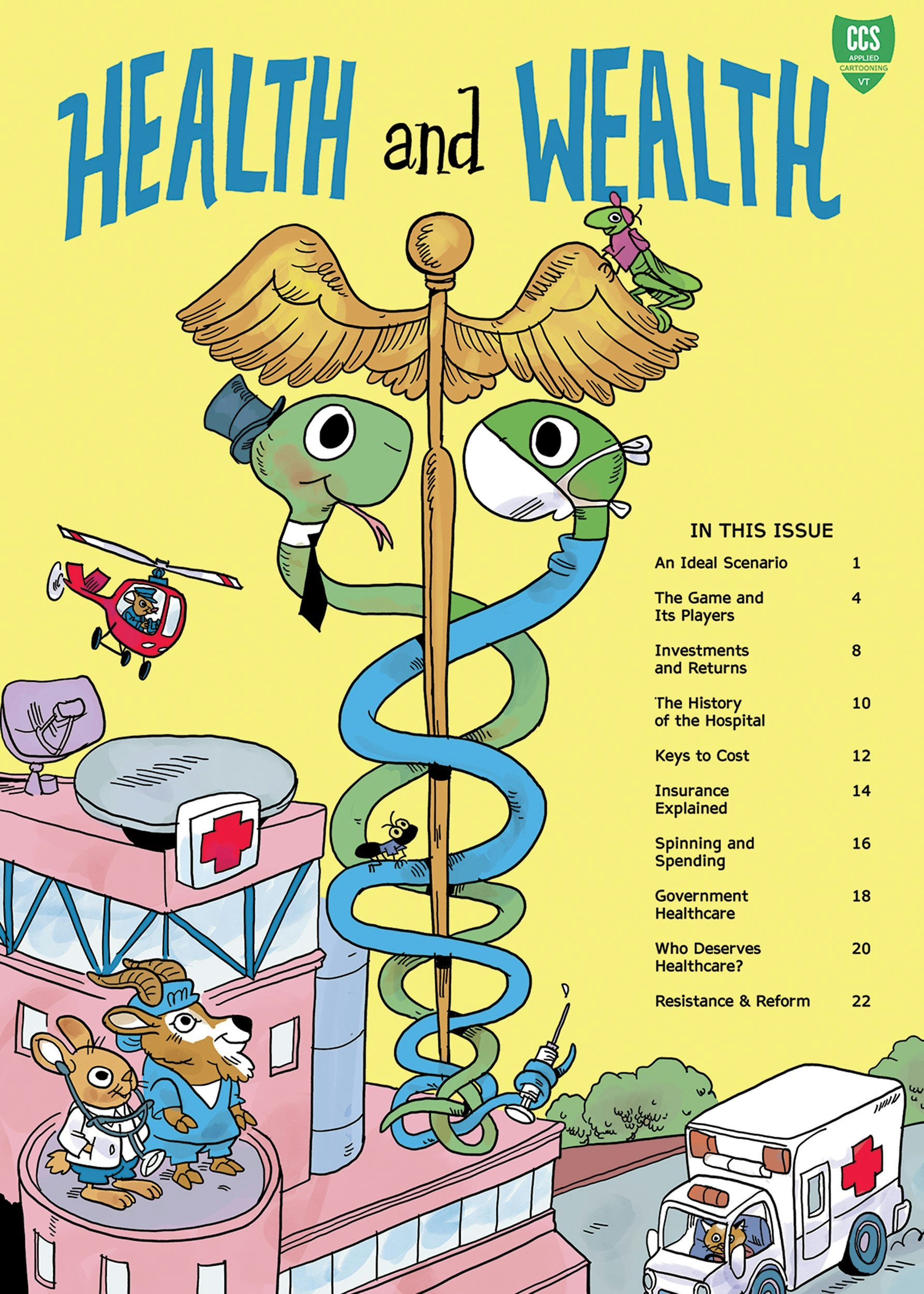

Health and Wealth: A Graphic Guide to the US Healthcare System (Center for Cartoon Studies, 2021)

Health and Wealth is the only one of the books under review that can be downloaded for free. That’s because James Sturm RI ’21, the founder and director of the Center for Cartoon Studies (CCS) and a lead cartoonist of the guide, sees it as a way to demystify the healthcare system. He hopes that advocates may use it to explain the stakes.

Why is healthcare in America both more expensive and worse than that in other countries? It’s a system nobody likes but everyone submits to. Medical debt remains the largest form of debt in the United States, and even affects about one in six households with health insurance.

Sturm and his collaborators from both the CCS and Radcliffe—including Sturm’s Radcliffe Research Partners, Harvard undergraduates who helped research the specifics of hospital billing practices and the medical industry—detail this system in illuminatingly specific terms. As of 2018, more than 16 million people worked in healthcare, from contact tracers to virtual experience specialists. Spending has grown from 5 percent of the US economy in 1960 to about 18 percent today. Yet “the US ranks close to last in healthcare quality, efficiency, and access to care” among industrialized countries. This is partly because of a change of how care is distributed: People used to get care at home. Now hospitals are the norm. Expensive and often driven by business interests, these hospitals changed how care was distributed. “Hospitals shifted resources away from caring for the chronically ill and towards acute care (which was more profitable.)”

Sturm’s team has taken care to make complicated legal matters as clear as possible. The book is amply illustrated with animals—bird patients and walrus doctors—who take their inspiration from Richard Scarry books. In one image, a mouse lies in bed. A caption explains, “Though in a hospital bed, the patient is being billed a more costly out-patient rate.” The mouse asks how much the procedure will cost. A rabbit wearing blue scrubs urges the mouse not to think of health as a question of cost, but as the caption bluntly explains, “Doctors can make extra money by selling the drugs they prescribe.”

Why is change so hard to come by? “The healthcare sector continues to spend more money lobbying Congress than another industry,” says the guide. Between 1999 and 2018, this sum was staggering: $4.7 billion. And yet it is Medicare—federal health insurance—that is most efficient, for both patients and hospitals.

Sturm and his colleagues set up a GoFundMe to distribute the book. To date, they have sent a copy of the book to each member of Congress. The cost of this distribution could barely cover a few days in the hospital.

Madeleine Schwartz is a regular contributor to the New York Review of Books and the New Yorker.