Crystal Z Campbell’s Haunted Creations

Installation Marks Centennial of Tulsa Race Massacre

Crystal Z Campbell works in film, installation, sound, painting, and text. This month, she installed the exhibition Notes from Black Wall Street (Or How to Project Yourself into the Future) at ahha Tulsa to mark the centennial of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, in which a white mob attacked the Black neighborhood of Greenwood, destroying homes and businesses and killing hundreds. Campbell is finalizing a video installation at Oklahoma Contemporary and, at the end of the month, will release a hybrid book/anthology with guest writers, titled After 1921: Notes from Tulsa's Black Wall Street and Beyond. As the David and Roberta Logie Fellow and the Film Study Center Fellow at Radcliffe, Campbell is creating a film called SLICK, which builds on the exhibition to illuminate the legacy of the massacre in Tulsa. We asked Campbell, who was recently named a 2021 Guggenheim Fellow in fine arts, about her process and vision. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Radcliffe: Where do you find the inspiration for your work?

Campbell: I often use my creative practice to home in on a subject or event I want to learn more about. In this case, despite being a product of Oklahoma public schools and universities from pre-K through receiving my BA in studio arts, I had not heard of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Another artist mentioned the massacre when I was living in New York about 10 years ago, and it seemed to be something that got at the core of a code of silence around critical state and national histories that shape us into the present, even though it remained largely a public secret until recent national coverage and pop culture thrust it into attention with shows like HBO’s Watchmen.

Radcliffe: What is a workday like for you?

Campbell: Being a freelance artist and experimental filmmaker requires a wide range of skills that are cultivated with each project, but that also means that each day in the studio has a different to-do list. The bones of my creative practice require research skills, writing to apply for support or grants that frame the work and sometimes writing a rough script or outline for a film project in addition, producing and developing the work, considering how the viewer will engage with the work while securing the materials needed to produce the work or finding a fabricator or designer to assist with that part of the project.

For instance, last week, I was installing an exhibition at ahha Tulsa, in Oklahoma, which commemorates the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. It is my first solo painting exhibition, and I specifically chose to work with one archive from the former Greenwood community that showed residents fishing and reclining along a river bank, embracing modernity and sprawling across the hoods of Fords, climbing trees, and lounging across front lawns. This particular set of vintage photographs is so important as a counternarrative, because so much of what came up when I was doing my preliminary research on the Black community of Greenwood showed only depictions of the aftermath of the race massacre: burning buildings, rubble, and depictions of some of the several hundred wounded and dead upon the streets. A lot of material has been kept under lock and key in personal and institutional archives, but it felt deliberate that the most widely circulated images of Greenwood––deemed one of the most wealthy enclaves of Black America––was that it could be, and was, destroyed. I often wonder how artwork can both amplify and shift the perception and register of an event or person or historical instance.

The artist and her father package work for ahha Tulsa in the living room that doubles as a studio. Photo by Crystal Z Campbell

I lived off Greenwood Ave. for several years when I resided in Tulsa, and upon arrival, I was surprised that so little of the structure from the rebuild, even, was retained. When I moved to Tulsa in 2016, there were two sets of commemorative plaques in the ground, each one too small to read clearly, and to this day, some of the plaques have been pulled up with new development and never replaced or have just gone missing. The ghost of a memorial plaque says so much. It is a metaphor for what has happened to the community and history of the place, which is that we have a placeholder and we know something was here even though we cannot grasp what it is.

The losses are incalculable: loss of people, of familial and community bonds, of creativity, of enterprise, of generational wealth, of the banal every day, of service, of memory, of justice, of answers, of elders, of youth, of historical knowledge, of laughter, of love.

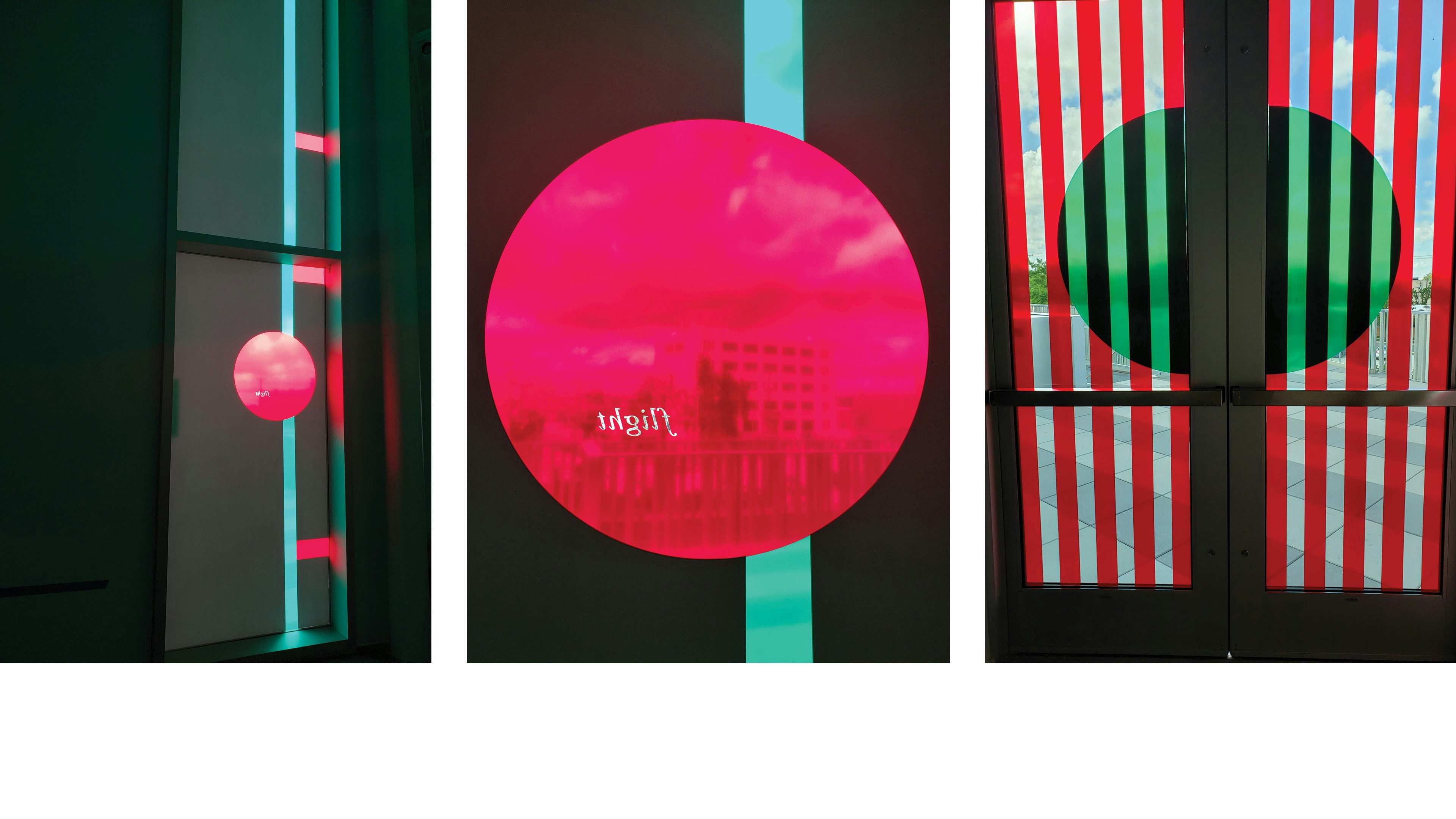

At ahha, the show included nine medium- and large-scale paintings and 100 small paintings mounted on a custom-designed structure. Each wall of the V-shaped structure is nearly 40 feet in length and is intended to symbolize a quarter of a century. I wanted to create the work as a proposal for a monument, as there is currently no single monument in Tulsa that honors the victims of this event. The paintings, over archival photographs, use many different types of paint and marker and collage, in addition to glass beads, metal, and fabric. The paint is purposefully very thick in places, to recall scars or the way history is embedded in our bodies. It’s worth noting that all of the large paintings are of women or groups of women. So much of the narrative advances the men of Greenwood, but I wanted to highlight these women and what I have yet to find out about their lives.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made me more cautious of how I work and of working in proximity with people, which made things more challenging. But perhaps a silver lining is that, rather than working with an assistant to prep and pack the paintings, my father stepped in to assist with these paintings. Additionally, I did some mock layouts of the exhibition in my living room.

A typical recent day has entailed finalizing the design with my Radcliffe research assistant and the fabricator, conducting Zoom visits, answering e-mails, prepping files, writing artists statements, applying for other opportunities to keep the work in motion, taking walks, bulk cooking to last for a few days at a time, reviewing video files for an project, editing a publication, designing a public art installation for Rudisill Regional Library, in Tulsa, and so on.

Radcliffe: How did you land on film as the format for SLICK?

Campbell: I’ve made work about the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in hundreds of paintings, in photographs, and in essays and other writing, and I have a forthcoming hybrid artist book and anthology with guest writers that I’ll publish with Visual Studies Workshop at the end of May, in time for the centennial. It still feels like there is much I haven’t even scratched the surface of, but I want to make a feature film that is both poetic and non-narrative. The film work will combine the performative gestures with local history, and associative references, to begin exploring the story in its now myth-like quality in addition to the ways the history of the massacre shapes the present. It’s been interesting given the 100 paintings are arranged almost like a set of film stills and require a certain slowness to read, while the film format is truly a sequence of still images, that can be read and organized very intently. With the medium of film, however, I can use time and history as mediums, allowing me to synthesize and distill archival and original content, and sound and image, in one contained form. I also want to rupture the expectations of film, and how manipulative they can be, in guiding and shaping our perception of history and narrative.

Radcliffe: What aspect of your artistic process might surprise people?

Campbell: Some of my future interests include the convergence of time-based art and public art; I want to push my work into the realm of public art and complicate notions of permanence, text, and memorializing in upcoming projects. In my creative process, I’ve actually been trying to tap more into ancestral knowledge and be guided more by intuition, which often gives stronger impressions the more time I spend with and honor the land in any particular place.