Exploring Liminality

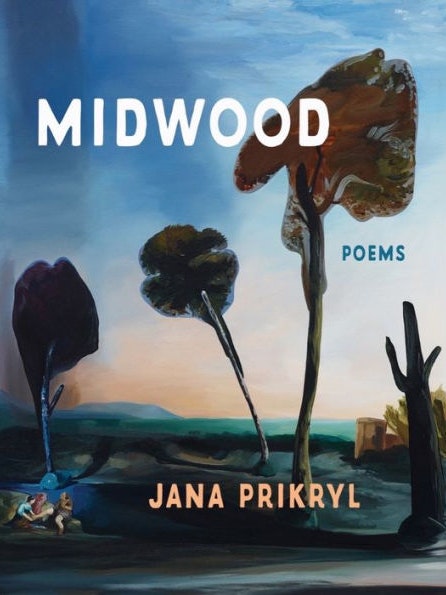

In Midwood, the poet Jana Prikryl mines dreams, recollections, and personal epiphanies to meditate on midlife.

During the pandemic shutdown, the poet Jana Prikryl RI ’18—who by day works as the executive editor of the New York Review of Books—undertook a personal challenge: to write a poem a day. In the early morning hours, before her then-three-year-old son woke up, she crawled out of a window in her Brooklyn apartment onto a fire escape—overlooking a small ravine, on the other side of which is the Midwood neighborhood—to jot down a few lines, sometimes inspired by her dreams, other times by the urban greenery before her.

The resulting work is Midwood (Norton, 2022), Prikryl’s third book of poetry and a jam-packed collection of sparsely punctuated verse about, she told the Globe and Mail in an interview, “motherhood and midlife and the longing for all kinds of connection.” The 113 poems, steeped in liminality yet grounded by a sense of place and the passing of the seasons, roam the author’s psyche and personal history, offering deeply relatable imagery and flashes of humor along the way.

Radcliffe Magazine: What’s your process? How do you know when a poem is fully cooked?

Jana Prikryl: A new phrase or line usually snags in my mind and gets the poem going. What’s odd is that my metaphors for this tend to be mechanical; the words have to “snag,” and I need to feel they have some “traction” on the page, that they’ve engaged some set of “gears.” I guess this means that as I’m writing a poem something about the process has to estrange the words I’m using—making my own utterance strange or foreign to me. If it’s working, there’s a feeling that the words are vibrating with an extra dimension or meaning that I’m not fully in control of, and that vibration directs the poem to its closure. But knowing when a poem is finished is a very mysterious subject, and I’m not sure I’m qualified to comment on it.

RM: You wrote these poems while practicing social distancing during the pandemic. How did being confined to one place affect your writing?

JP: Most simply the chaos helped me focus—things were hard and constantly busy that first year and a half, before our son went back to school in September 2021, but little else was going on, our routine was isolated to our apartment and every day was very repetitive. I think the energies that were forcibly contained during that time somehow flowed into the poems; they seem charged with an urgent wish to communicate, or rather to figure out what “contact” means between a writer and a reader. I discovered that this is as much about listening to the opposition between us as generating whatever we’d call “intimacy”—a lot of these very short, interior poems really function as dialogues; the pressure of the other person listening/reading is there giving them shape and force.

RM: There is a great deal of repetition in Midwood—not only phrases recur but also titles of poems (including the 24-part "Midwood" series and seven discrete poems titled “The Noncello”). Is there a connection between this choice and the sameness of pandemic life?

JP: A plausible theory! But it was more the result of my fascination with repetition, structure, and narrative, which I explored in my first two books as well. Here in Midwood, in the poems titled “The Noncello” I was parceling out a more linear narrative in contrast to the surrealism of the book’s dream-based poems, and the “Midwood” poems attempt to create a thematic structure for the whole collection. The second half of my first book, The After Party, contains a long sequence called “Thirty Thousand Islands,” and perhaps the “Midwood” poems were an attempt to go farther, both formally and emotionally, in that direction. But then the themes of the “Midwood” poems—a sense of stasis and rootedness at midlife, a daily reckoning with circumstances beyond one’s control, the effort to really see the mundane reality around you, the possibility that it might contain beauty—were especially unavoidable in that first year and a half of Covid.

RM: You mentioned in an interview that this collection includes your first experiments in writing from dreams. Can you tell me more about that?

JP: Actually not my first—there are some poems based on dreams in my first two books, The After Party and No Matter, and I’ve always felt slightly uncomfortable about them—worrying that the material is too much of a readymade; but then that’s part of its formal appeal. And that discomfort seemed to have potential as I started to focus on this new collection. I wondered if the discomfort might be concealing something from me, so I decided to try writing poem after poem based on dreams, first thing in the morning, with as little “thought” as possible—in effect transcribing the way my brain wanted to tell the “story” of each dream as soon as I woke up. Later I revised the poems into their current forms, but fundamentally they felt like experiments with narrative, attempts to catch something of what happens when we try to remember any experience that’s urgently important to us: Are you remembering what happened, or are you constructing the past in the course of telling it?

RM: What’s your relationship with your readers? How often do you consider them during the writing process?

JP: All the time and never? It’s a bicameral process, I guess. The poem only “turns out” if I’m completely absorbed in the language, in whatever’s happening on the “page”—but to some degree that absorption includes anticipating how a reader will respond. One of the things I find hard about writing is the (to me) necessary feeling of being entirely alone and free, while composing a poem—it’s a task that nobody else is able to help me with! I find this unnerving. In that sense the inner ear that anticipates a reader’s responses is a form of comfort, it slightly alleviates the pressure of self-reliance. And then later in the process, while revising, I try to read more as a stranger—a new reader, no longer alone inside the poem—which may be why I find revision more enjoyable than writing the first draft.

RM: You were born in Czechoslovakia and moved with your family to Southern Ontario, in Canada, when you were six. Does your first language influence your writing?

JP: Yes, I think I was lucky with the timing of our immigration, because English got to me early enough to reorganize my brain—it became my “first language,” the language I dream in, etc.—but it also happened by the time I had a clear idea of myself as a person (and after I’d had to learn German, at the age of five), so I was aware of language as a thing separate from me, an instrument I had to relearn, almost a kind of impediment. I’d probably have loved playing with words, and have stood a bit outside myself when dealing with language, even if we’d stayed in Czechoslovakia and I’d become a Czech writer, but—who knows! The degree to which English has shaped me is something I can only wonder at. I do think the quiet Czech voice that sometimes speaks up in my head makes me especially interested in conducting experiments on English.

RM: You’ve said that your day job feels very different from writing poetry but has made you the writer you are today. If given the chance, would you work on your poetry full time—or do you feel it would kill the magic?

JP: I got to enjoy this tremendous freedom at Radcliffe, in 2017–2018, and never tired of it. It’s hard to imagine a writer declining a chance to write full-time. Every manuscript is different, though; at Radcliffe I wrote No Matter (Tim Duggan Books, 2019) and was able to read many books that became important to that collection. Whereas Midwood was a manuscript that could be, or maybe needed to be, written in medias res—in brief moments amid the business of family life and daily work during a slightly impossible year or two. That sense of constraint, of playing a tug-of-war with time, with narrative (how a subject exists in time), are central to these poems. It’s possible that the next manuscript will want a slightly more generous allotment of time! I’m not sure—we’re still in negotiation.

Ivelisse Estrada is the editor of Radcliffe Magazine and a senior writer at Harvard Radcliffe Institute.