The Halls of History: A Personal Course in the Legacies of Slavery

Through the combined power of coursework and a research project for this initiative, Sydney Lewis ’22 finds a direct connection to Harvard past.

The summer after my first year at Harvard, I spent eight weeks as an undergraduate researcher with Harvard’s metaLab, a team of artists, engineers, and designers who specialize in interdisciplinary approaches in the digital humanities. My primary project consisted of cataloguing the African American studies curriculum at Harvard from its inception, in 1960, to the present day, tracking changes and continuities along the way. I came away from my foray into curricular history with a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes and shapes a curriculum, from the pedagogical forces of the day to radical student movements. Most of all, my experience granted me an understanding of and an appreciation for my place in time.

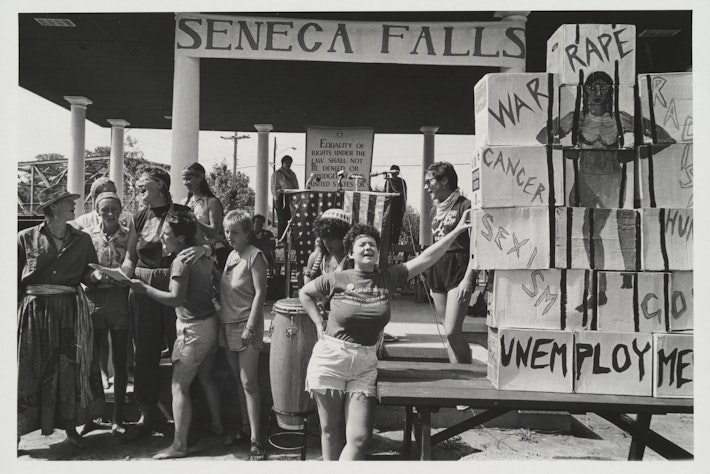

This feeling of being situated in time has been amplified by present-day circumstances. Living, as we are, through a global pandemic, massive movements for racial justice, and domestic political turmoil, the sense of our own contemporaneity—of our cemented place in the halls of history—has been magnified. The act of looking at the present retrospectively is a foreign feeling that seems to define our present era in particular. This heightened awareness of how the future will inevitably see us has given my work meaning, knowing that someday Harvard will be judged according to how it chose to ignore its past or acknowledge it.

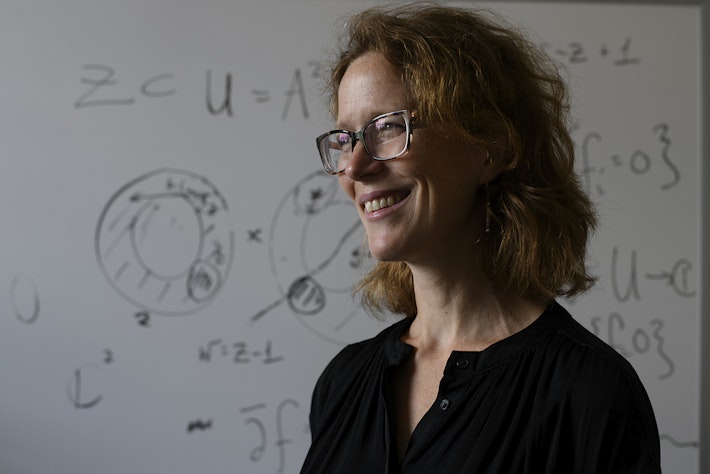

Themes of time and memory have also been a mainstay in my coursework. As I began taking classes on legacies of slavery, I was presented with the conundrum that Harvard, even as it enshrined itself as a beacon of light, a herald of truth for the nation, was perpetuating the constructed lie of racial difference, including through the work of Professor Louis Agassiz, the anatomist and museum curator Thomas Dwight, and Professor and Dean J.B.S Jackson in the 19th century. At the same time, professors, curricula, and institutions at the University were building on Harvard’s legacy of slavery—which included the housing of enslaved people on campus—by continuing to uphold the culturally dominant view of Black people as inferior. In particular, leading up to my work with the initiative, I took three classes that introduced me to the horrors of slavery and its lasting effects: Can Art Inspire Social Justice, with Professor Sarah Lewis; Race, Capitalism, and the Coming of the Civil War, with Professor Walter Johnson; and Fashion and Slavery, with Professor Jonathan Square. These courses interrogated the institution of slavery and, from it, extracted understanding of what it meant to be human; how people express themselves among complex matrices of power, race, and economic privilege; and what constitutes a citizen, making me realize that the study of slavery—including its legacy, its history, and its continued existence—is incredibly generative.

From this coursework, I began to develop my academic interest in art, justice, race, and slavery, specifically how they coalesce in historic and modern narratives. My journey to where I am now was shaped by the insights and tools these classes provided me. I came across these offerings serendipitously, but finding classes related to modern legacies of slavery should not be left to chance. That is why I’m so excited to be able to help build a resource for students like me, perhaps earlier in their studies, to forge a path through Harvard’s dense and at times overwhelming curricular offerings and to find coursework related to the legacies of slavery—however that looks like for them. This will not only be a useful tool to students and faculty but also challenge the notion that the study of slavery is solely the domain of history classes.

My research, as affirming and exciting as it is, can also carry doubts. I feel the all-too-common pressure to get the story “right,” whatever that means. As always, in times of personal confusion, I turn to the words of giants. Toni Morrison, in her essay “Moral Inhabitants,” writes that “the contours of academic scholarship are now and have always been: the equating of human beings with commodity, lumping them together in alphabetical order.” In other words, history has always been about codifying, categorizing, of necessarily viewing the big picture, even if that means sacrificing the individual. However, that does not mean this is the only approach. When reflecting on the transatlantic slave trade, specifically those who died on the Middle Passage, Morrison ponders what many historians do not: the possible existence of “a seventeen-year-old girl with a tree-shaped scar on her knee—and a name.” She goes on to ask, “Does the girl know that the reason that she died in the sea or in a twenty-foot slop pit on a ship named Jesus is because that was her era? Or that some great men thought up her destiny for her...?”

A similar thought runs through my mind as I casually flip through digital pages of archived course catalogs from the Harvard Medical and Law Schools. I wonder what young man held this in his hands 200 years ago. Where was he from? What was running through his mind as he traversed the steps of Langdell on the way to class? And what might he think if he knew that in 200 years, a young Black woman might walk where he walked, hoping to find a quiet place to write an essay on the racial injustice carried out in those very esteemed halls?

These kinds of questions, usually unanswerable but not entirely unavailing, have been endemic to my work. Just as Morrison questions the destiny of the 17-year-old girl, so do I question Harvard’s. As an institution, what is our destiny? Where does it lie? The past may have followed a certain path, but how we hold ourselves accountable to it, how we choose a more just, equitable path, and how we define ourselves to be viewed by future generations—that is ultimately up to us.

Sydney Lewis ’22 is a concentrator in African American studies and history of science with a citation in Spanish. She is a research assistant for the presidential initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery and spent her fall semester surveying Harvard’s historical curricular offerings—focusing primarily on the early 17th to 18th centuries—that engaged with slavery, specifically materials and the faculty involved in teaching Harvard students about race, abolition, and the institution of slavery. For the rest of the academic year, she will be looking at contemporary curricular offerings and materials on and related to race and legacies of slavery. She is a diversity peer educator in the Harvard College Office of Diversity Education and Support, a member of the Harvard Black Health Matters Conference executive board, and a dancer with the Harvard-Radcliffe Modern Dance Company.