From Woman To Human: The Life and Work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Though she wrote and lectured extensively on reforming marriage and the family, Charlotte Perkins Gilman rued the attention and notoriety that her own marriages and family life unavoidably attracted. She made headlines not only with her ideas, but with her life.

Gilman married Charles Walter Stetson in 1884, almost against her better judgment, and immediately began suffering terrible bouts of depression. Her famous short story, The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), a fictionalized account of a woman’s descent into madness, was based on her own experience of a deteriorating marriage and her resulting mental breakdown. Her solutions—divorcing Stetson and sending their daughter to live with him and his second wife—drew widespread public attention and criticism.

Gilman subsequently married her first cousin, George Houghton Gilman, in 1900. Press coverage inevitably included mention of Gilman’s earlier marriage and divorce. Yet unlike the marriage of her parents and her own first marriage, this one was a happy and fulfilling relationship that endured until Houghton Gilman’s sudden death in 1934. Her final years brought her the conjugal affection and domestic contentment she both longed for and sparred with her entire life.

Gilman’s post-partum depression and subsequent relationship to her daughter, Katharine, affected her attitudes toward reforming the institution of motherhood and the division of labor within the family. Mother and daughter moved to California in 1888, and Gilman immediately became incredibly productive, writing daily and lecturing widely. Yet while caring for her daughter as a single parent, she felt she lacked the freedom to work and earn a living as she wished.

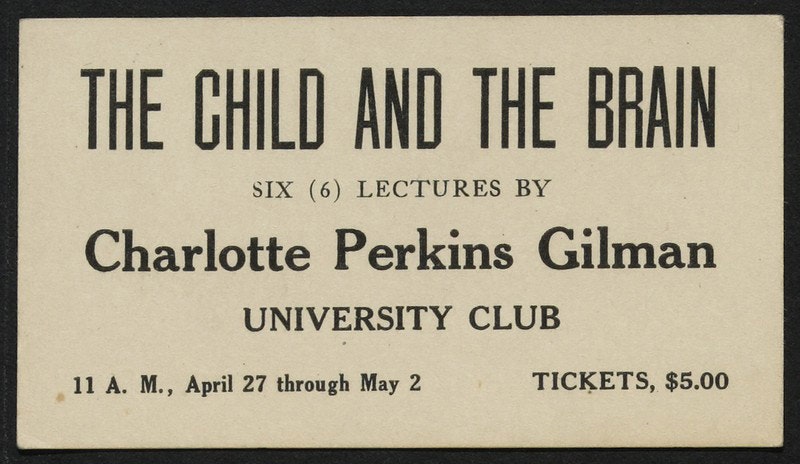

In Concerning Children (1900) and other works, Gilman propounded ideas about communal child rearing and education to free mothers from domestic servitude.

"When we do honestly admit that a child is being educated in every waking hour by the conditions in which he is placed and the persons who are with them, we shall be readier to see the need of a higher class of educators than servant-girls, and a more carefully planned environment than the accommodations of the average home."

Gilman also questioned why childrearing was done only by women. She felt that Walter Stetson had as much right to raise their child as she did. Gilman fictionalized many of her ideas about family and home in Herland (1915).

“But when we began to talk about each couple having ‘homes’ of our own, they could not understand it . . . A man wants a home of his own, with his wife and family in it.’

‘Staying in it? All the time? . . . Not imprisoned surely!’

‘Of course not! Living there—naturally,’ he answered.

‘What does she do there—all the time?’ Alima demanded. ‘What is her work?’”

“We had expected them to be given over to what we called ‘feminine vanity’—‘frills and furbelows,’ and we found they had evolved a costume more perfect than the Chinese dress, richly beautiful when so desired, always useful, of unfailing dignity and good taste.”

In her feminist utopian novel Herland (1915), Gilman introduced her readers to a country of women who worked cooperatively. Her characters were drawn in accord with the ideas Gilman presented in her nonfiction work The Home: Its Work and Influence (1903) and her serialized article "The Dress of Women" (1915).

In both of these works, Gilman railed against the condition of women who were relegated to a life of confining costume and care for child and home. She envisioned a world (imagined earlier by Melusina Fay Peirce, also) in which women were free from the drudgery of cooking and cleaning and could engage in intellectual pursuits—a world in which women threw off their corsets and breathed freely.

Gilman strove to understand the basis for the societal strictures that defined "woman" so narrowly. She was inspired by sociologist Lester Ward to investigate and trace the developments in human history that had led to such inequitable gendered divisions of labor. Gilman wrote Women and Economics, her most influential book during her lifetime, in a matter of several weeks during the fall of 1897. Its forward-looking chapters owed much to the Fabian socialists she had met during her first trip to England in 1896.

She was not alone in wanting to understand the constrictions of the day's society through economics: Thorstein Veblen's The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899) and Olive Schreiner's Woman and Labour (1911) both explored similar questions and were similarly influential around the world. Gilman began to see herself as part of an international community of activists, working toward a more egalitarian society. She received letters from around the globe, particularly from women who wanted her to know how much her work inspired them.

In This Our World, Gilman's first published volume of poetry, was published in England in 1896. As her works grew in number and scope, and as she continued to appear at international congresses and to lecture throughout Europe, more of her books and articles were translated into foreign languages. Women and Economics alone was translated into seven languages within a few years of its publication.

To celebrate the sesquicentennial of Gilman's birth, the Schlesinger Library has digitized Gilman's papers, with the generous help of the Cynthia Green Colin Fund. You may browse the collection finding aid to learn more about Gilman's life, and view her diaries, letters, writings, and drawings.