Judy Chicago: Through the Archives

Judy Chicago was born Judith Sylvia Cohen in Chicago, Illinois, on July 20, 1939, the oldest child in a family of secular Jewish liberals. Her father, Arthur, a Marxist labor organizer and post office worker, conveyed to his daughter a lifelong passion for social justice and a belief that the purpose of life was to make a difference. Her mother, May, a medical secretary and former dancer, recognized her daughter’s abilities and enrolled her at an early age in classes at the Art Institute of Chicago. Their household was alive with blues and jazz music, talk of contemporary fiction, and political awareness of the rights of workers, African Americans, and women.

While studying at the University of California, Los Angeles (BFA 1962, MA 1964), Cohen adopted her married name, Judy Gerowitz, and began to show her work locally. She soon found that, in order to be taken seriously as an artist, she was obliged to accommodate her aesthetic impulses to the prevailing modernist style. Struggling to find her place in the male-dominated art scene of Los Angeles, she discovered the literature of the women’s movement emerging in the late 1960s with "something akin to existential relief." In 1970 she announced her name change to Judy Chicago, an act identifying herself as an independent woman. Having embraced her feminist identity, Chicago set out to educate the world through her art. Her teaching and use of women’s history and the artistry of “women's crafts” revolved around her belief that “female experience could be construed to be every bit as central to the larger human condition as is the male.”

Early Career (1965–1973)

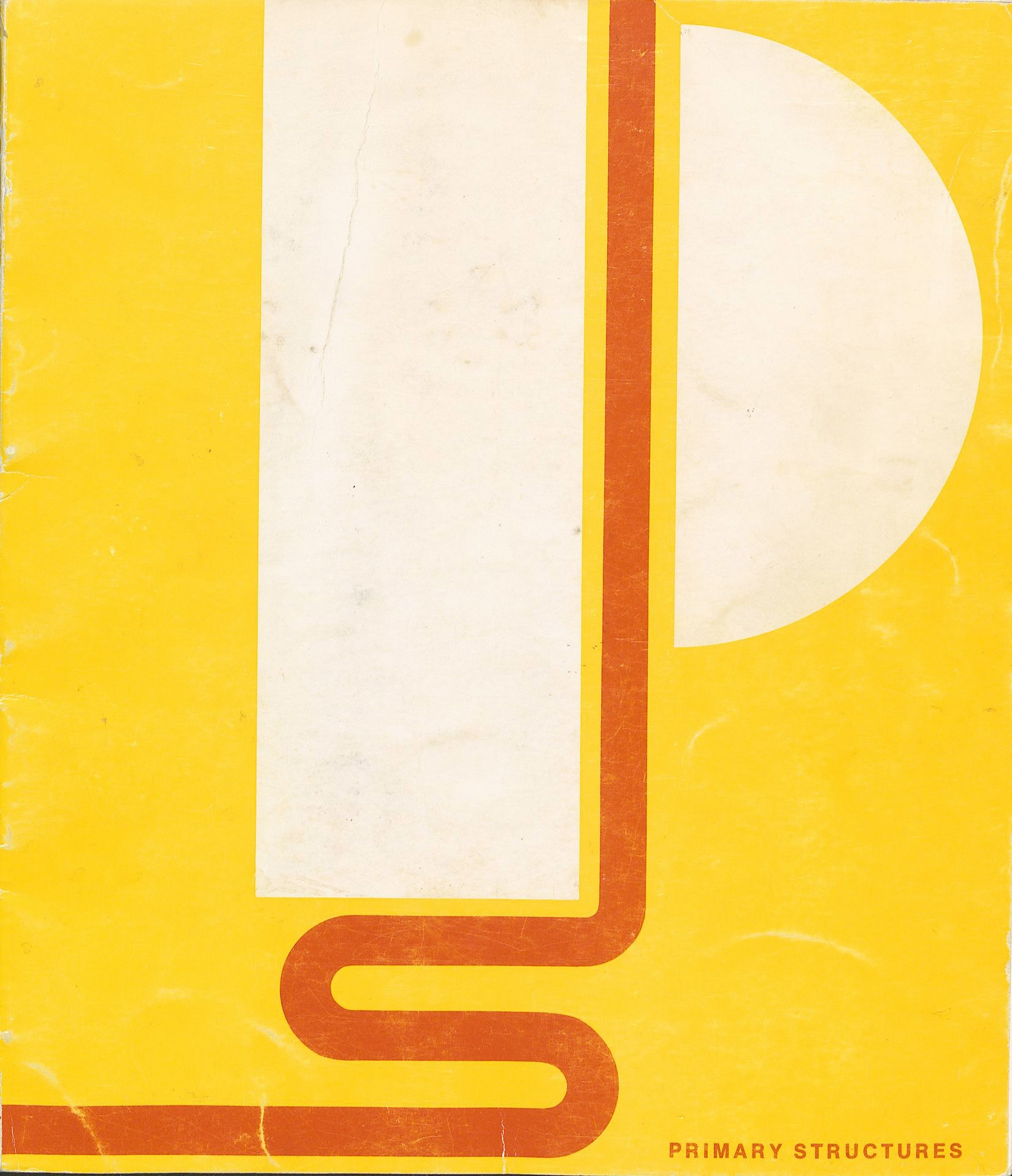

Reflecting on her early career, Chicago stated, “When I was a young artist in the burgeoning Los Angeles scene, I wanted, above all, to be taken seriously in an art world that had no conception of or room for female sensibility. In an effort to fit in, I accommodated my aesthetic impulses to the prevailing modernist style.” Like many of her peers, she became proficient in various technical processes. At auto-body school, she studied techniques for spraying acrylic lacquer paint—and through apprenticeships with boat workers and pyrotechnicians, she learned fiberglass casting and how to use fireworks. Despite creating works using the same techniques as her male peers and featuring similar imagery, reviews of her early pieces, such as 1964’s Car Hoods, singled out her art for being overtly sexual. In response, Chicago produced works focused on color and form that did not overtly address content. Several of these artworks, such as the sculpture Rainbow Pickett, were included in the influential Primary Structures exhibition in 1965. While generally well received, even these works were criticized by some for using a “female” pastel color scheme.

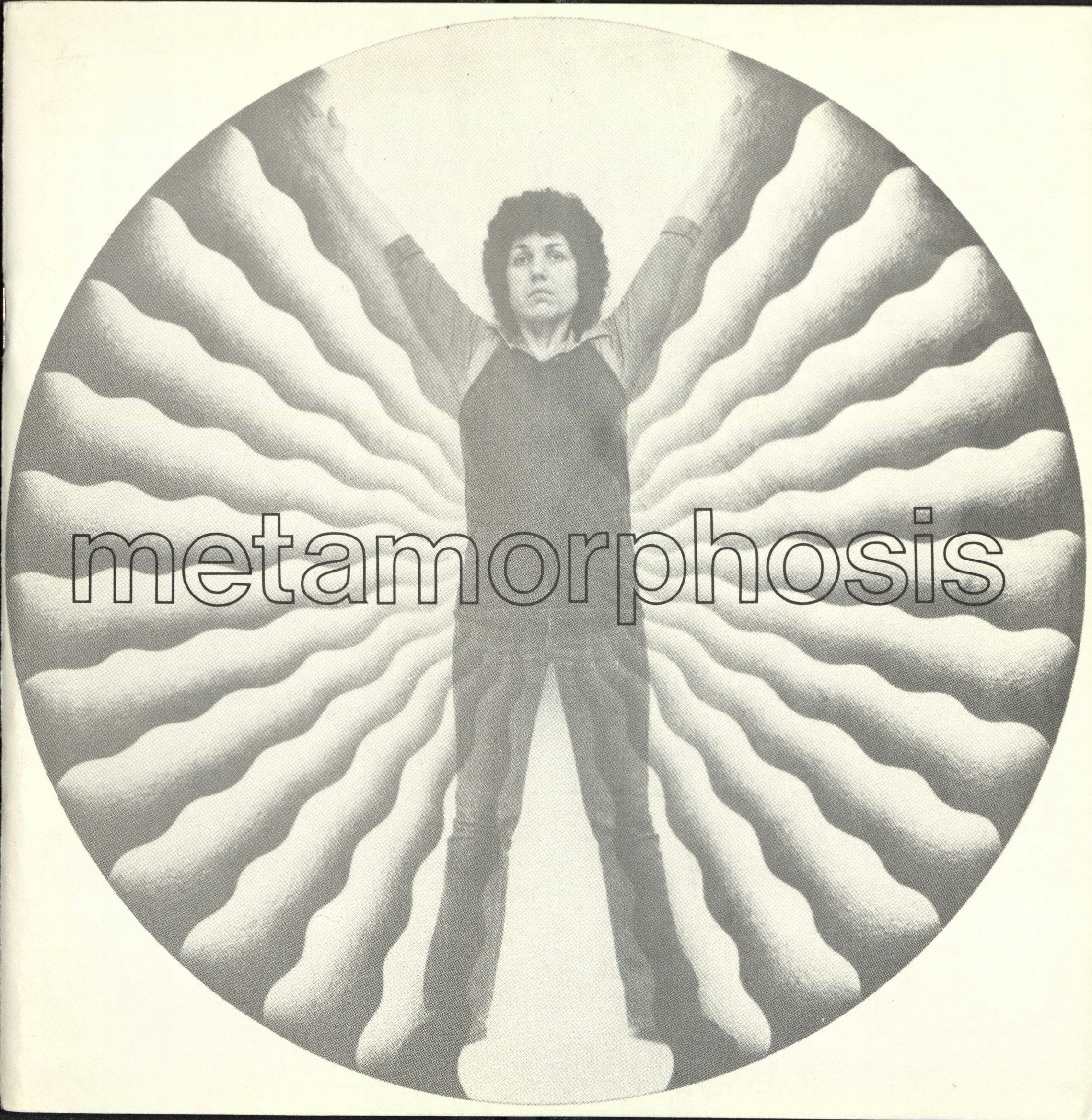

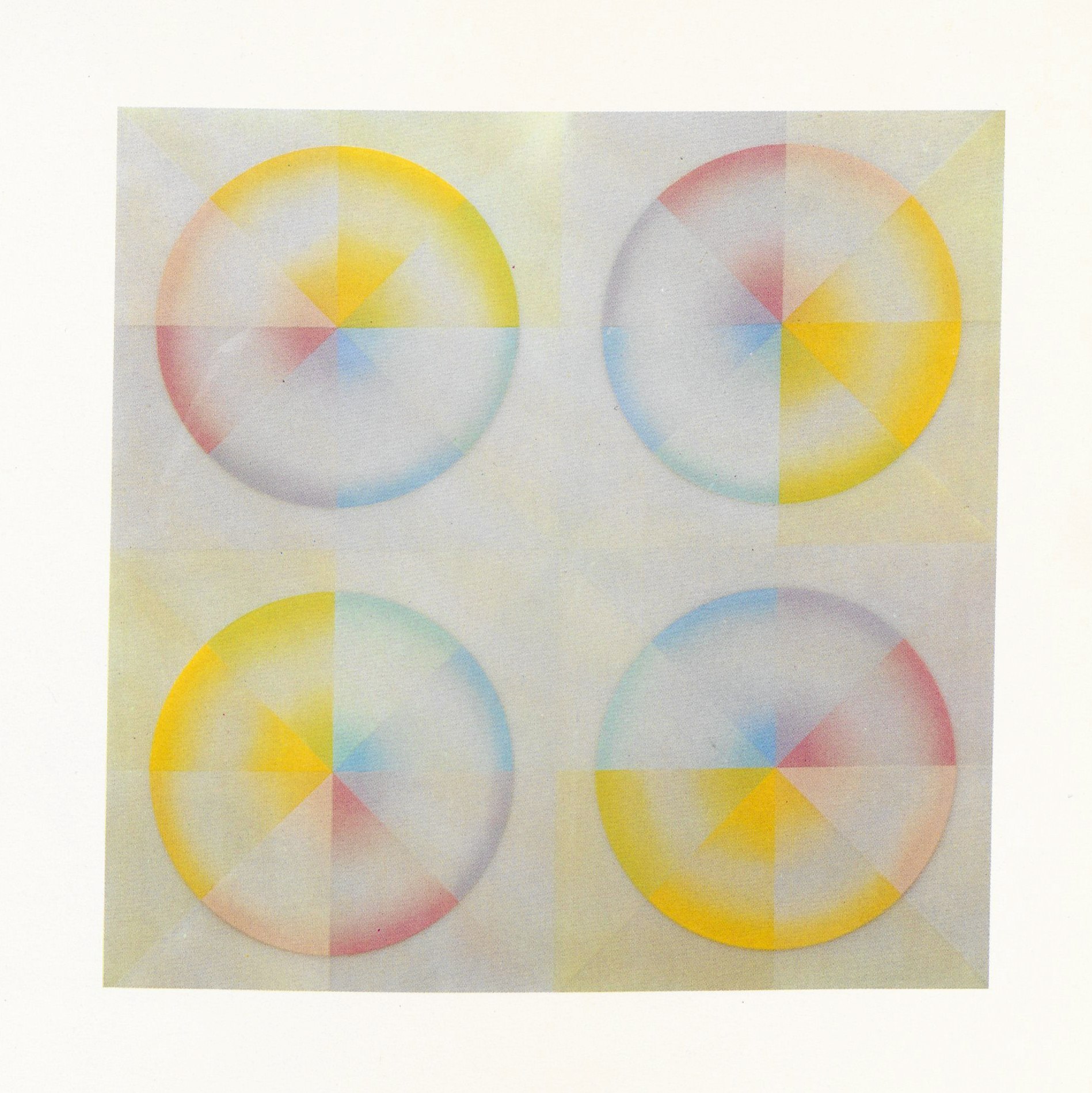

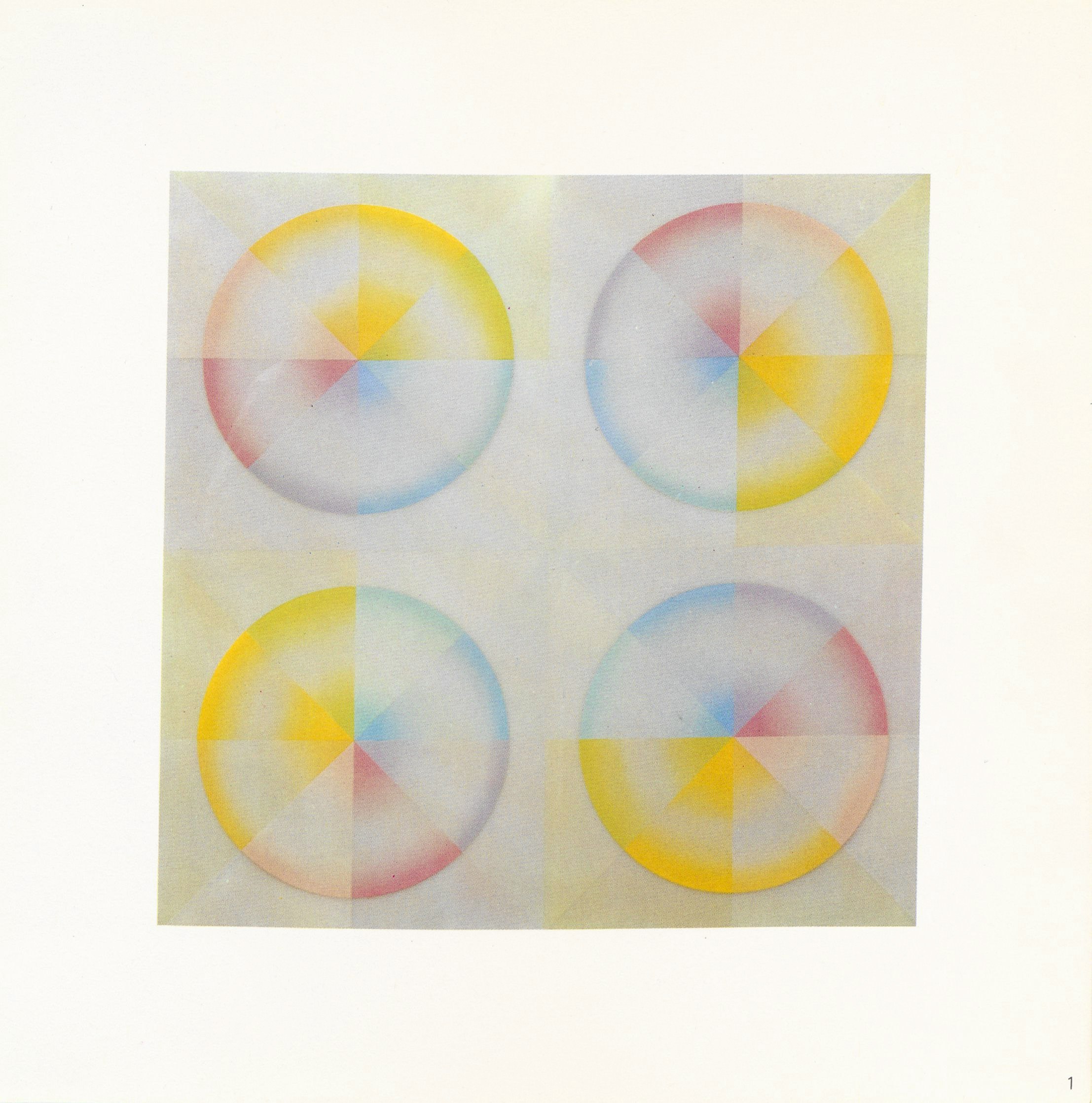

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Chicago produced several series of large paintings made from sprayed acrylic lacquer on acrylic sheeting, which used color and space to suggest movement and emotion. Chicago said of these paintings, "they allow me to deal with three different feeling states, to establish and then break down form, and to manifest a wide range of direct sensations based on central or female core imagery." Paintings from these series, such as Pasadena Lifesavers, mark the beginning of Chicago’s journey as a feminist artist.

Early Feminist Teaching (1970–1974)

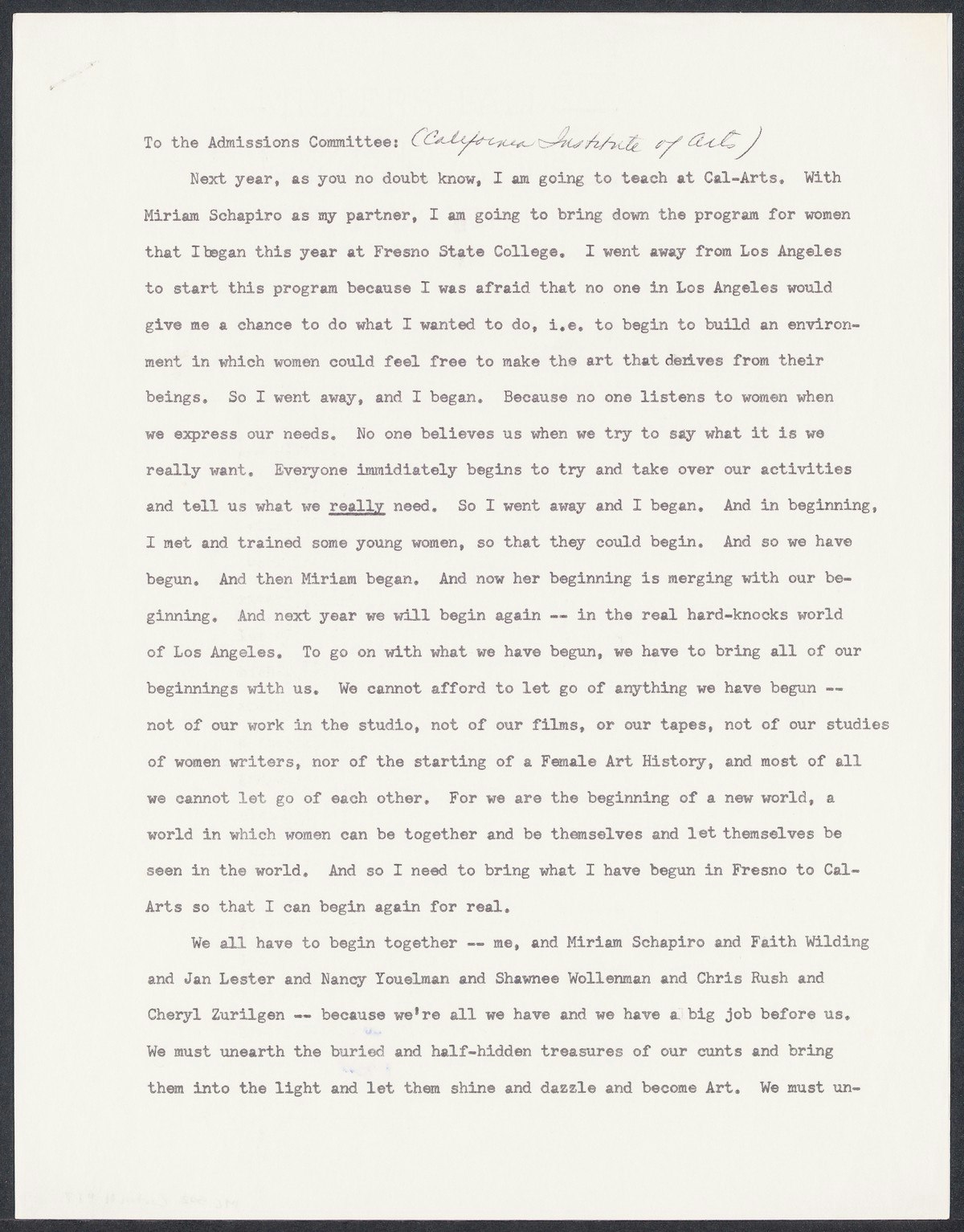

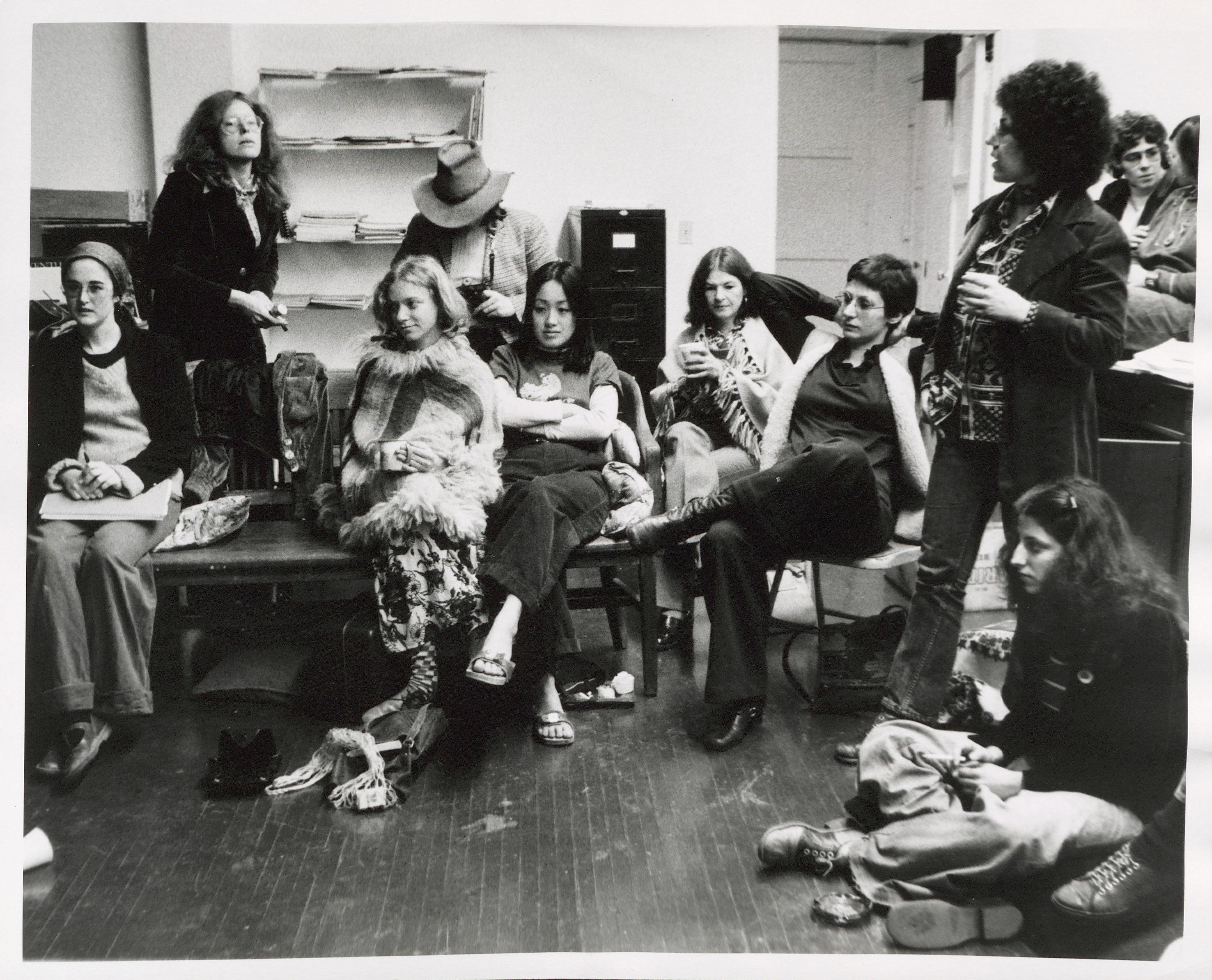

In 1970 Judy Chicago started the first feminist art program in the United States at Fresno State College, with the goal of helping young women studying art to become professional artists. After a year in Fresno, Chicago returned to Los Angeles, where she founded the Feminist Art Program at the California Institute for the Arts (CalArts) with her fellow feminist artist, Miriam Schapiro. A highlight of Chicago’s tenure at CalArts was creation of the feminist art installation and performance space Womanhouse in 1972. Staged by students in the Feminist Art Program along with several local women artists, Womanhouse transformed a condemned mansion into “the repository of the daydreams women have as they wash, bake, cook, sew, clean and iron their lives away.”

Determining that it was “impossible to have a feminist program within a male-dominated school,” Chicago left CalArts in 1973 to found the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW) alongside the graphic designer Sheila Levrant de Bretteville and the art historian Arlene Raven. The first independent feminist art program in the United States, FSW sought to enable women artists to work in a feminist context. FSW rented an old art school in downtown Los Angeles, which they christened the Woman’s Building after the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Reserving meeting and studio space for themselves, they sublet the remainder of the building to a feminist art gallery, a feminist bookstore, and a range of feminist political organizations “assuring that the exhibition of women’s work could take place in an environment that was connected to a wide female community.” Chicago resigned from FSW in 1974 to work on The Dinner Party.

Creating The Dinner Party (1974–1979)

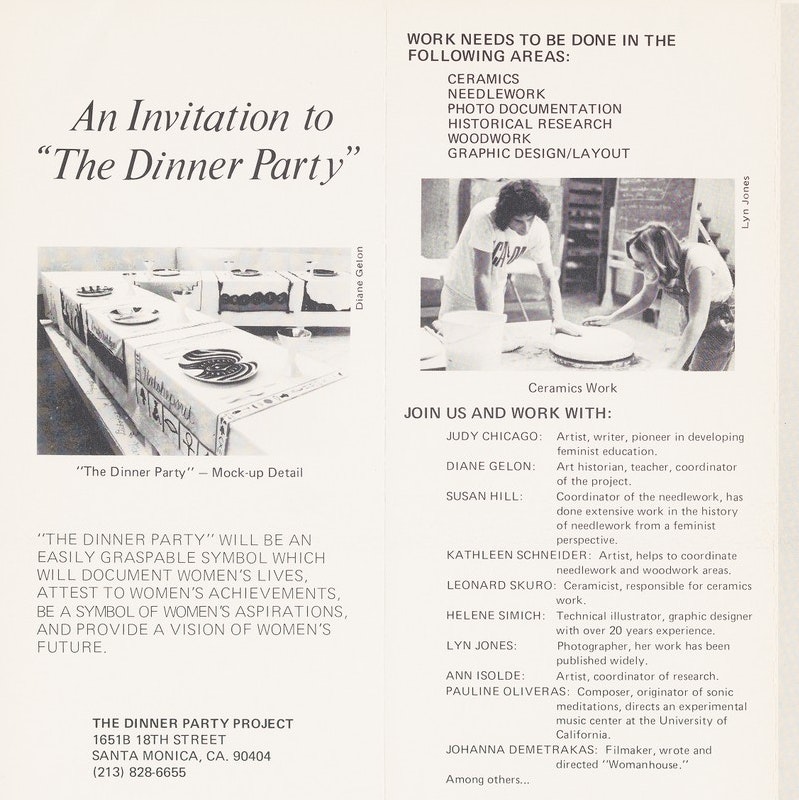

Featuring 39 place settings on an open triangular table resting on a ceramic tiled platform, The Dinner Party depicts and celebrates the lives of mythical and historical women, each of whom represents a historical period in Western civilization. The 39 women were selected from among thousands of women researched for the project based on their accomplishments and their contributions to the betterment of conditions for women. Each place setting contained a painted, often carved, porcelain plate featuring a vulva-butterfly motif on a runner decorated using a variety of fiber art techniques. The platform, called The Heritage Floor, was inscribed with the names of 999 other women “intended to suggest that the achievements of such individual women as those presented at the table had to be seen against the background of this larger female history.”

Although she initially planned The Dinner Party as an independent work, Chicago soon concluded that the scope of the project was too vast for her to complete on her own, and she engaged volunteers to help her realize her vision. Working in her studio in Santa Monica, California, Chicago guided nearly 400 volunteers over eight years as they embroidered runners in the needle loft, researched the lives of women, assisted in the creation of the plates, and engaged in fundraising and publicity events. Believing that the volunteers should learn about women’s history and empowerment, Chicago instituted potluck dinners and consciousness-raising sessions, many of which were filmed and included in Johanna Demetrakas’s documentary, Right Out of History: The Making of Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party.

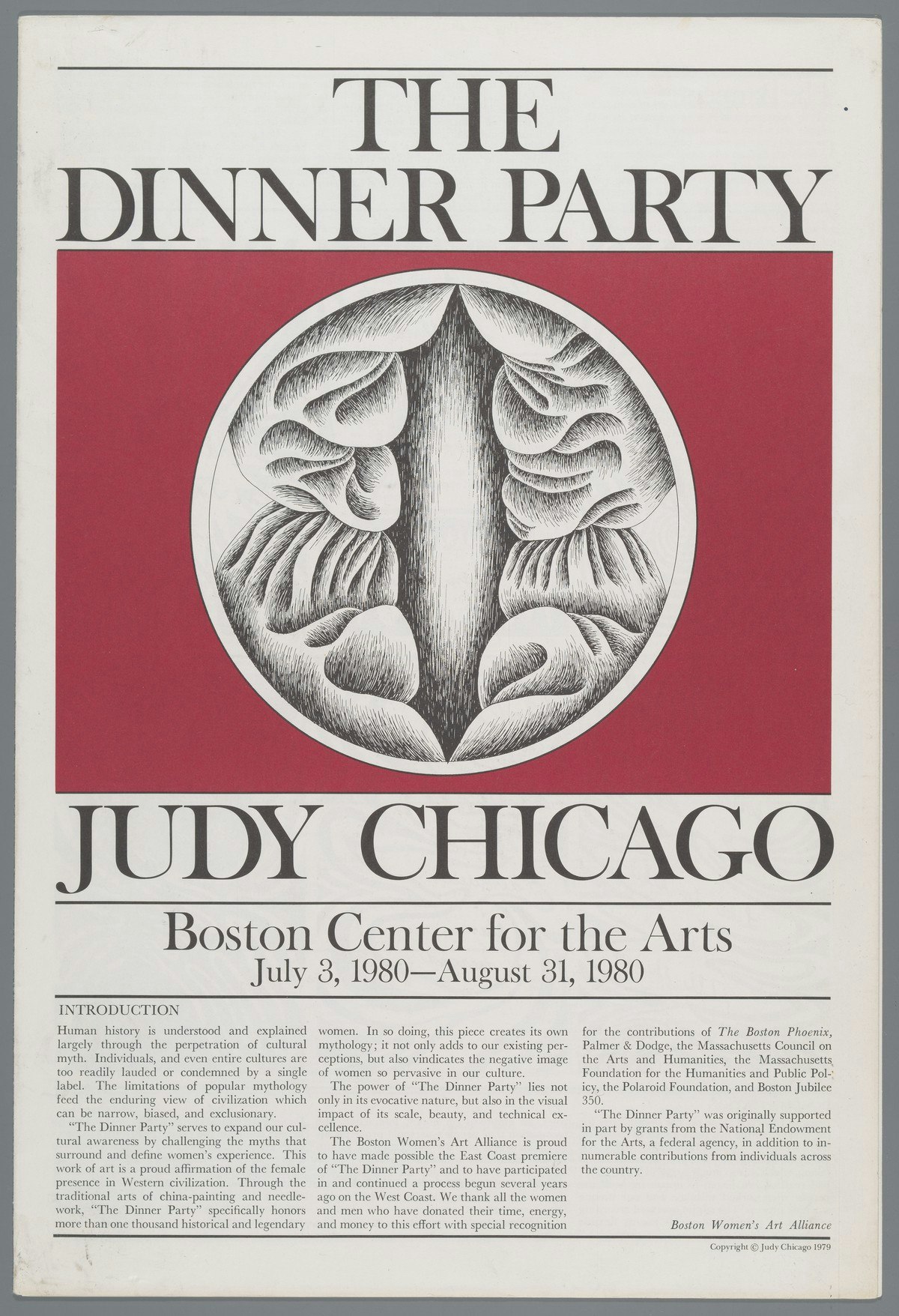

The Dinner Party Exhibition (1979–2007)

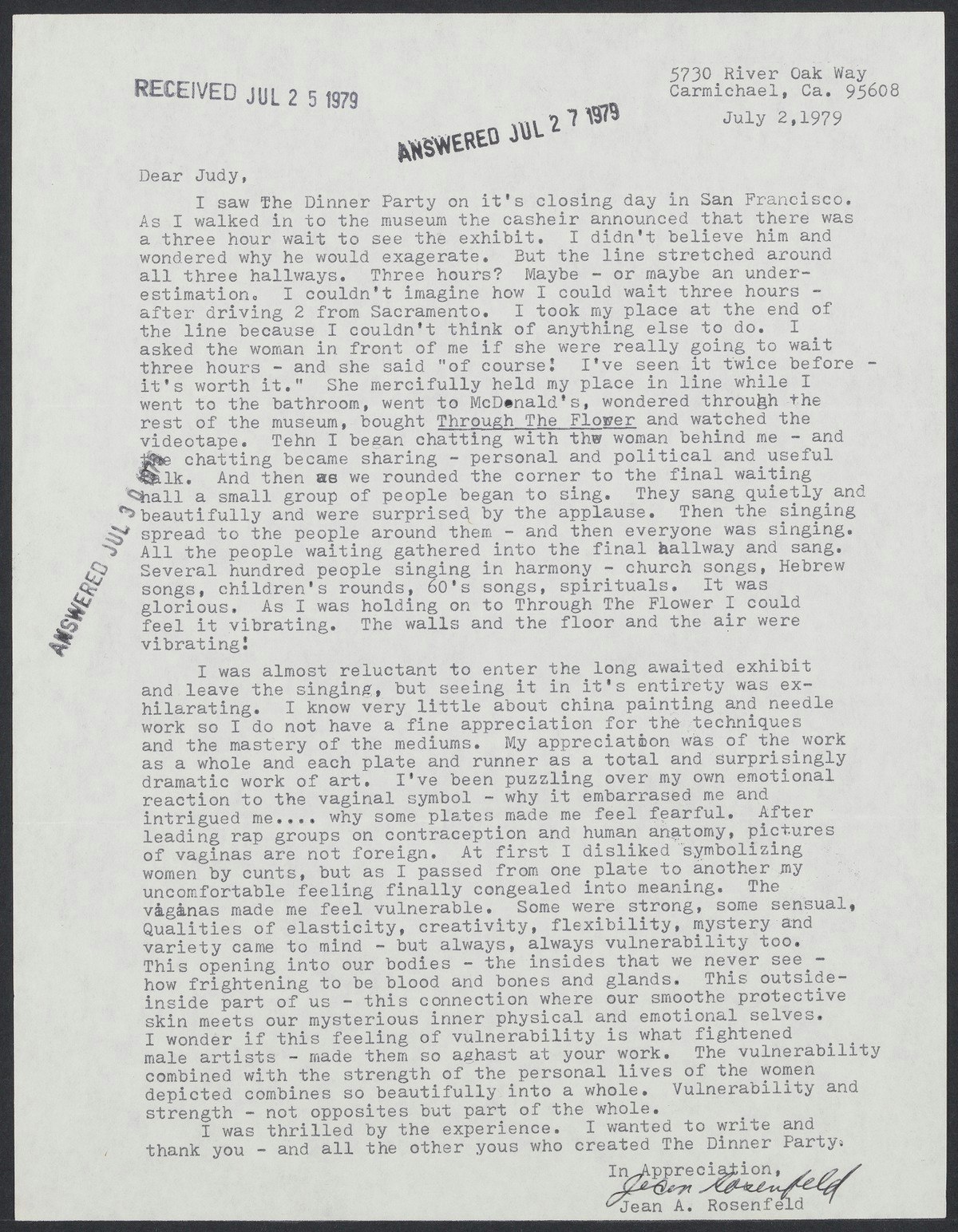

The Dinner Party opened at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art in March 1979. Despite attracting thousands of viewers, some of whom waited in line for five hours to enter the exhibit, a generally negative response from art critics led to canceled showings across the United States. Determined to see The Dinner Party, grassroots groups in Atlanta, Boston, Brooklyn, Chicago, Cleveland, and Houston organized fundraisers and brought the exhibition to alternative venues in their cities, including a theater space in Houston and the Cyclorama in Boston. The Dinner Party then toured Canada, Europe, and Australia before going into storage in 1988.

In 1990 Chicago donated The Dinner Party to the University of the District of Columbia, where it was slated to be installed in the soon-to-be renovated Carnegie Library. False reports in the Washington Times claiming that the university was purchasing The Dinner Party from Chicago for “nearly $1.6 million” led to debates in Congress, which controls the university’s funding. Even after being apprised of the falsity of the claim, several members of Congress threatened to withhold funds for the library renovations if the university acquired the piece, which they labeled “offensive” and “pornographic.” When a conservative student group joined the protest, Chicago withdrew her gift.

Dr. Elizabeth Sackler, a philanthropist and admirer of Chicago’s work, purchased The Dinner Party in 2001. In 2002 she gave the piece to the Brooklyn Museum, where it has been the central attraction at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art since it opened in 2007.

Birth Project (1980–1985)

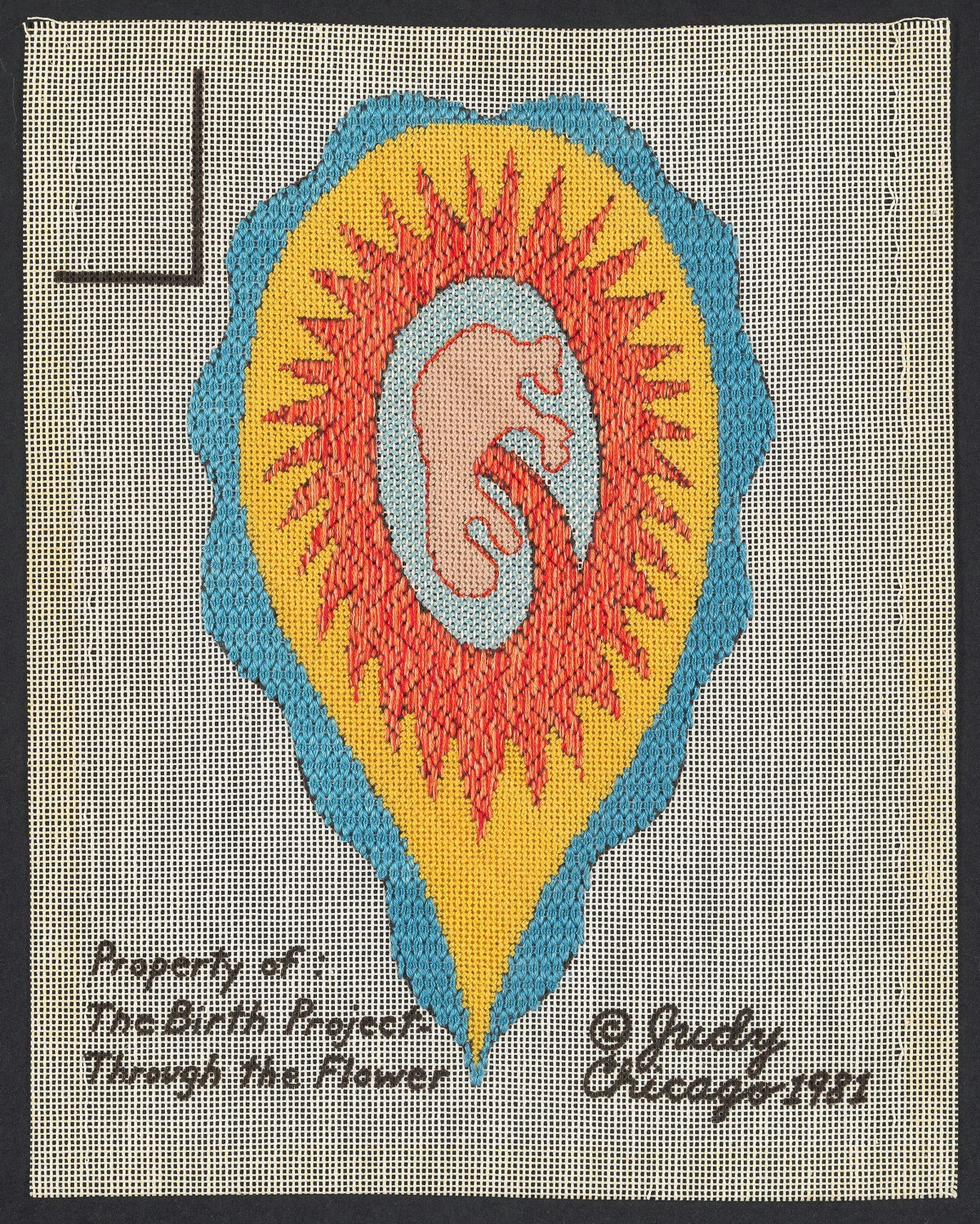

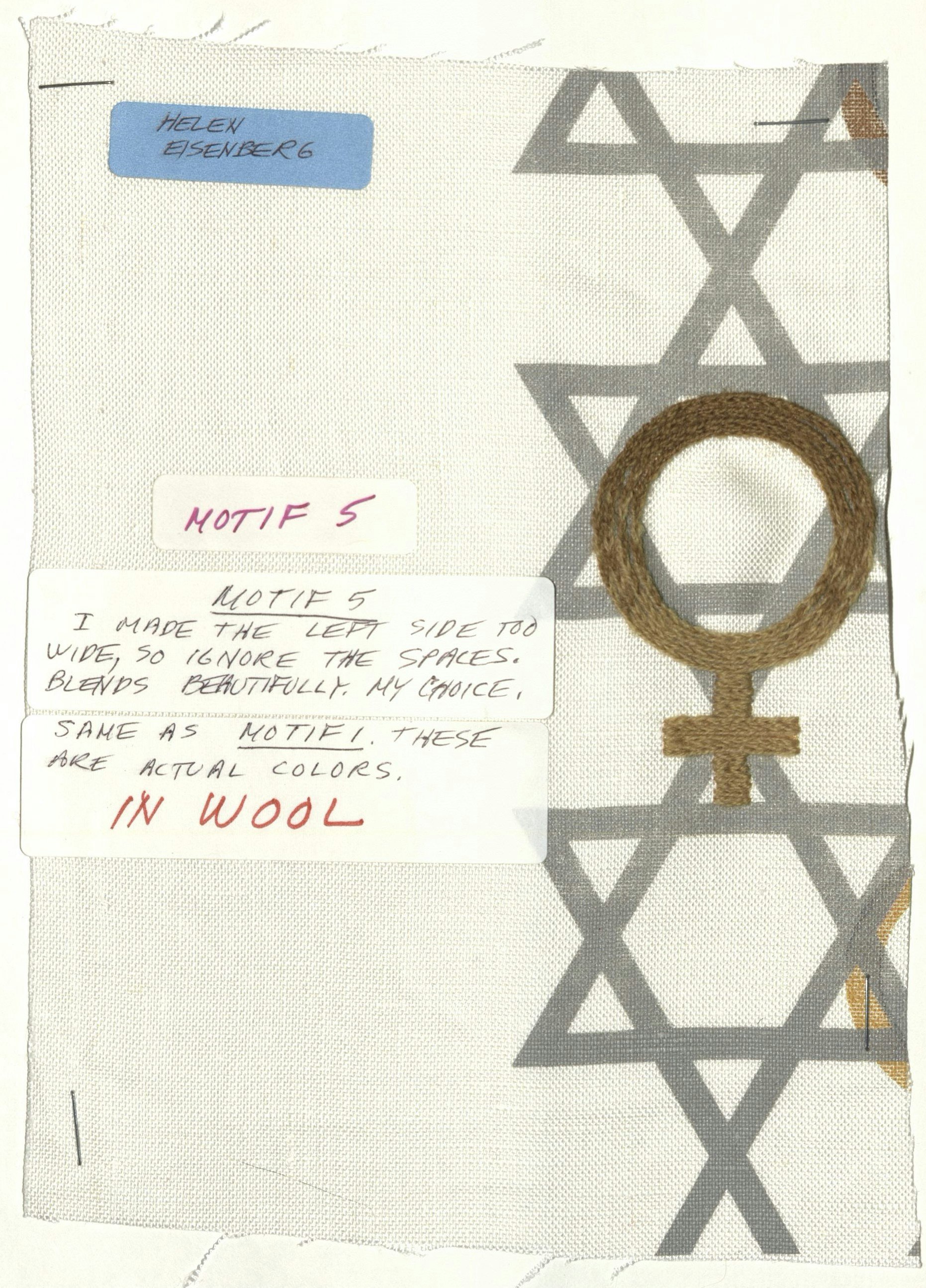

The Birth Project was a collaboration between Judy Chicago and more than 150 needleworkers. It resulted in the creation of dozens of images combining painting and needlework that celebrate various aspects of the birth process. Needleworkers, who submitted applications to work on the project from across the United States, as well as from Canada and New Zealand, were asked to demonstrate their needlework skills on a sampler Chicago designed. Accepted applicants, working individually or in small groups, were sent a piece bearing one of Chicago’s Birth Project designs to work on. Regular check-ins and reviews were conducted through the mail or in person at work sites, Chicago’s studio, and at regional meetings across the country. In addition to working on Chicago’s designs, needleworkers agreed that any communications they had with Chicago, including questionnaires, reviews, and interviews, could be used in Birth Project exhibitions.

Exhibitions, consisting of a small selection of pieces with panels detailing their creation, were mounted in venues ranging from professional galleries to shopping malls in an effort to “introduce images of birth and information about the reality of women’s lives to a wide audience of viewers.” Eventually, pieces were given by Chicago’s nonprofit organization, Through the Flower, to institutions throughout the United States. The Schlesinger Library was fortunate to receive the piece Thou Art the Mother Womb, which can be viewed on the second-floor landing.

Collaboration and Reinvention Beyond the Birth Project

Chicago’s work continues to evolve while she remains steadfast to her artistic and feminist vision. Over the past three decades, she has produced an eclectic body of works, including Powerplay (1982–1987), an exploration of masculinity; Voices from the Song of Songs (1997–1999), a series of prints representing Chicago’s interpretation of the Old Testament book Song of Songs; and Kitty City (2003–2005), a watercolor series tracing the history of the feline species that expresses Chicago’s devotion to her cats.

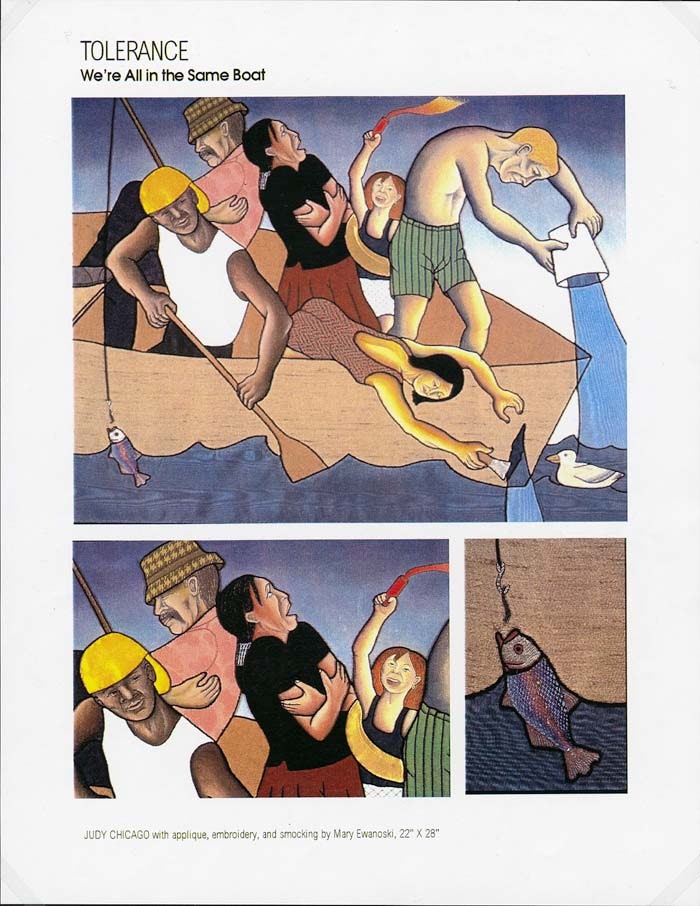

Resolutions: A Stitch in Time (1994–2000), was a collaborative project using painting and needlework images to explore seven basic human values: family, responsibility, conservation, tolerance, human rights, hope, and change. The project, which Chicago described as “an art exhibition that fuses painting and needlework in a series of images which are intended to inspire hope, encourage positive change, and educate a diverse audience toward a shared global vision,” premiered at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City and traveled to eight venues.

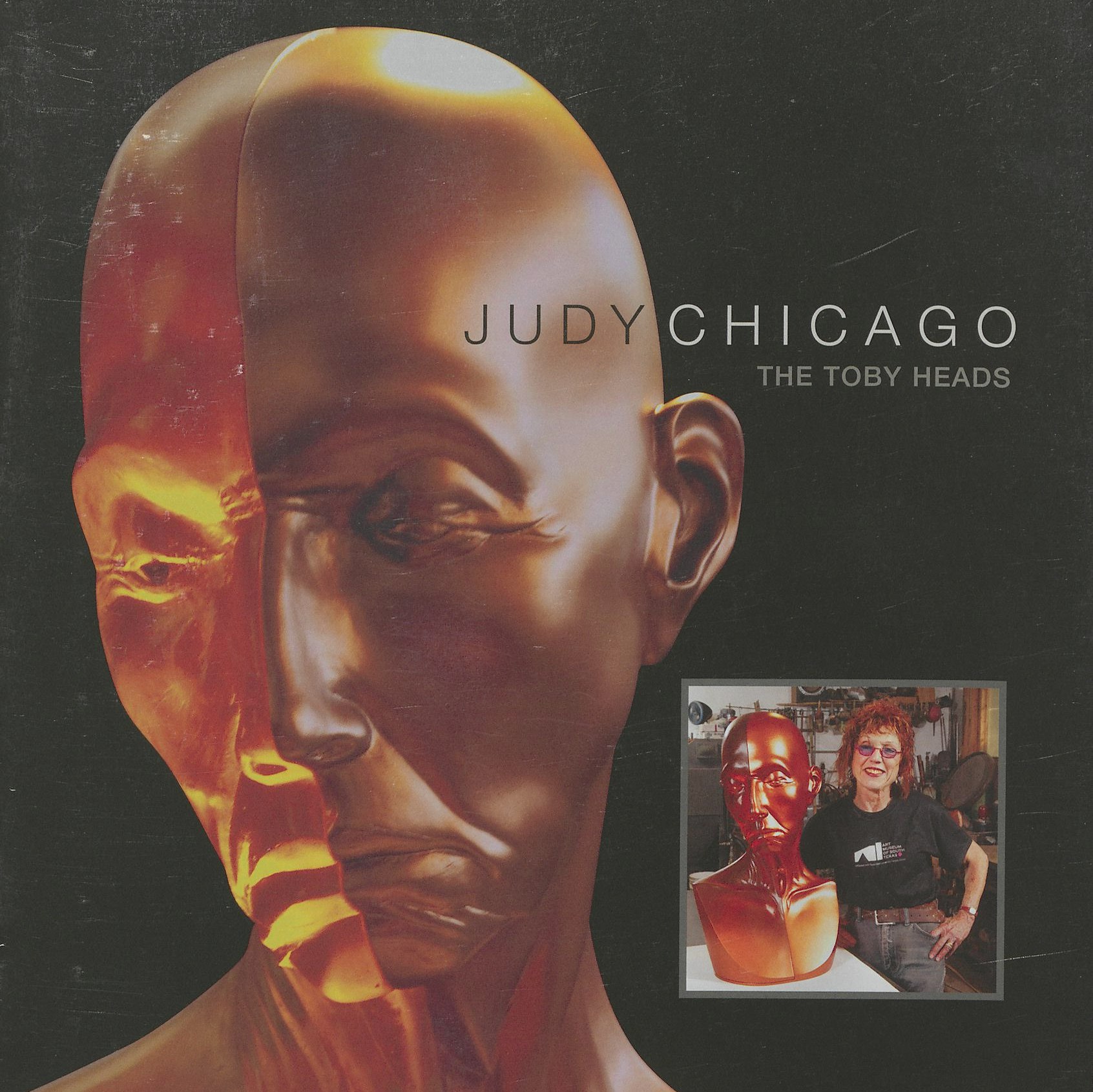

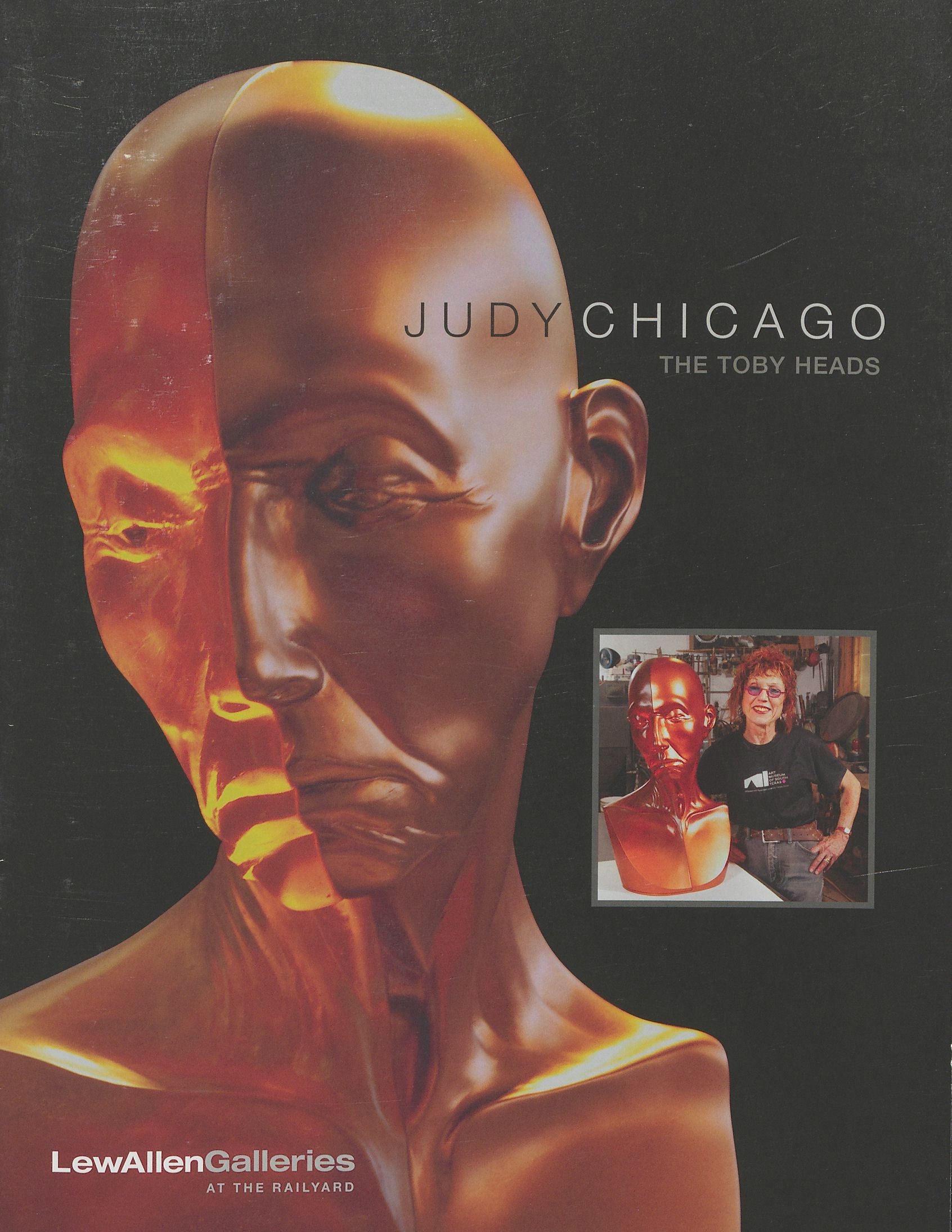

Chicago’s work in glass (2006–ongoing) represents one of the most recent phases of her artistic journey. Having incorporated glass into several of her mixed media projects, including the stained-glass tryptich Rainbow Shabbat in the Holocaust Project, Chicago turned her focus to works created solely in glass, a medium she explored as an artist in residence at the Pilchuck Glass School in 2003. Since her residency, she has used cast, fused, and etched glass and other glass techniques in works such as the Toby Heads and the hand series. This recent work expresses her technical skills while conveying physical and emotional expression.

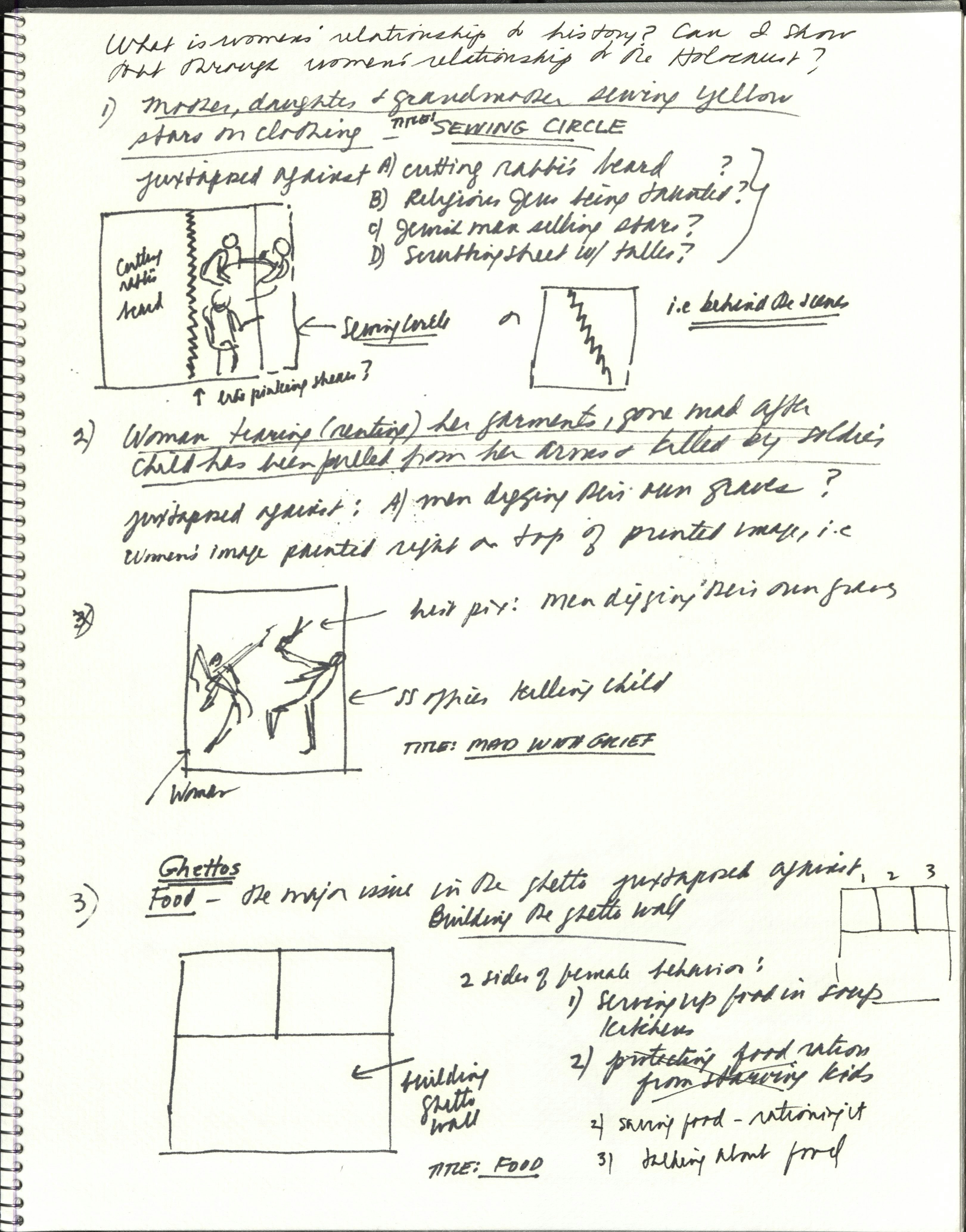

Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985–1993)

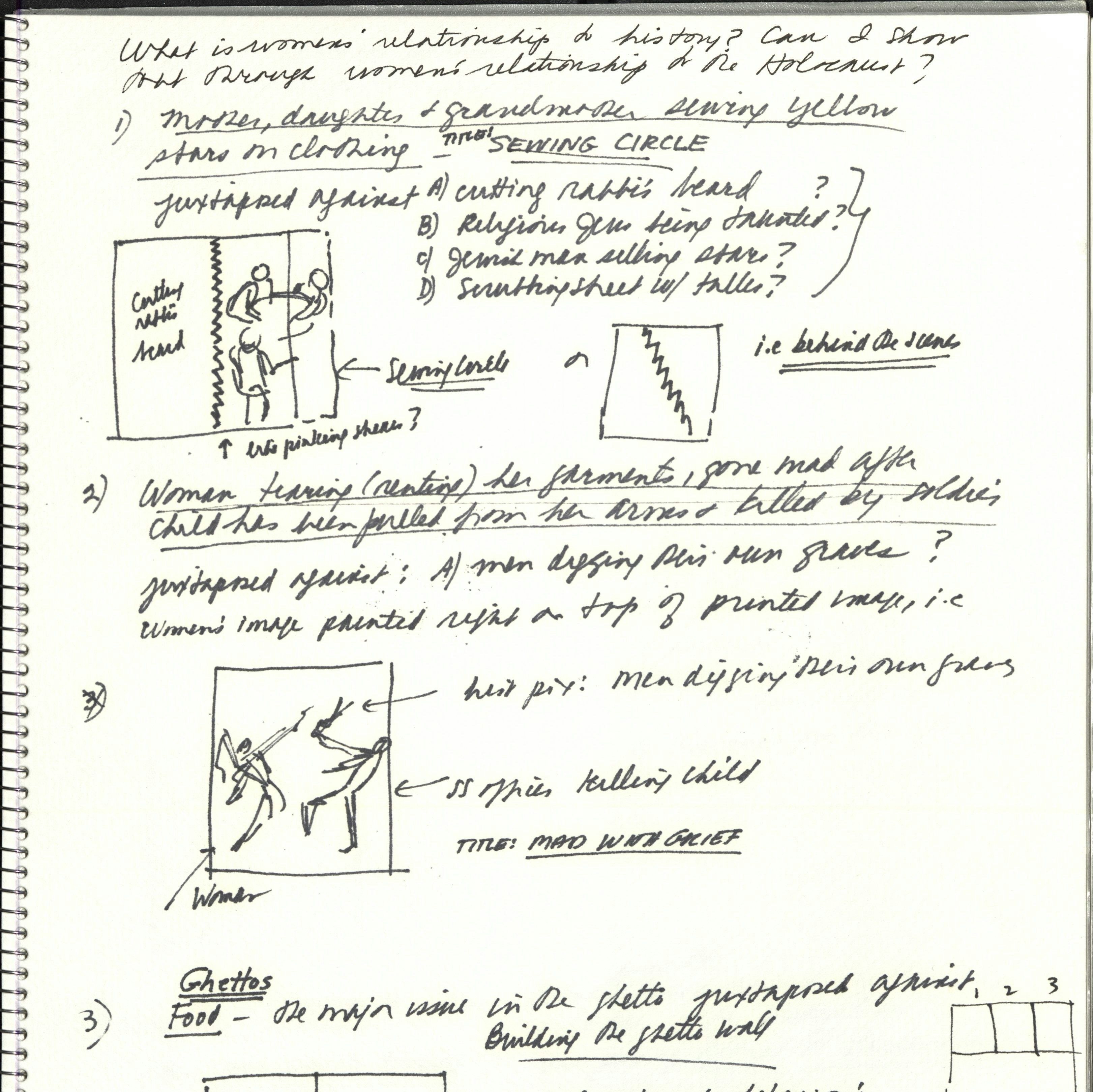

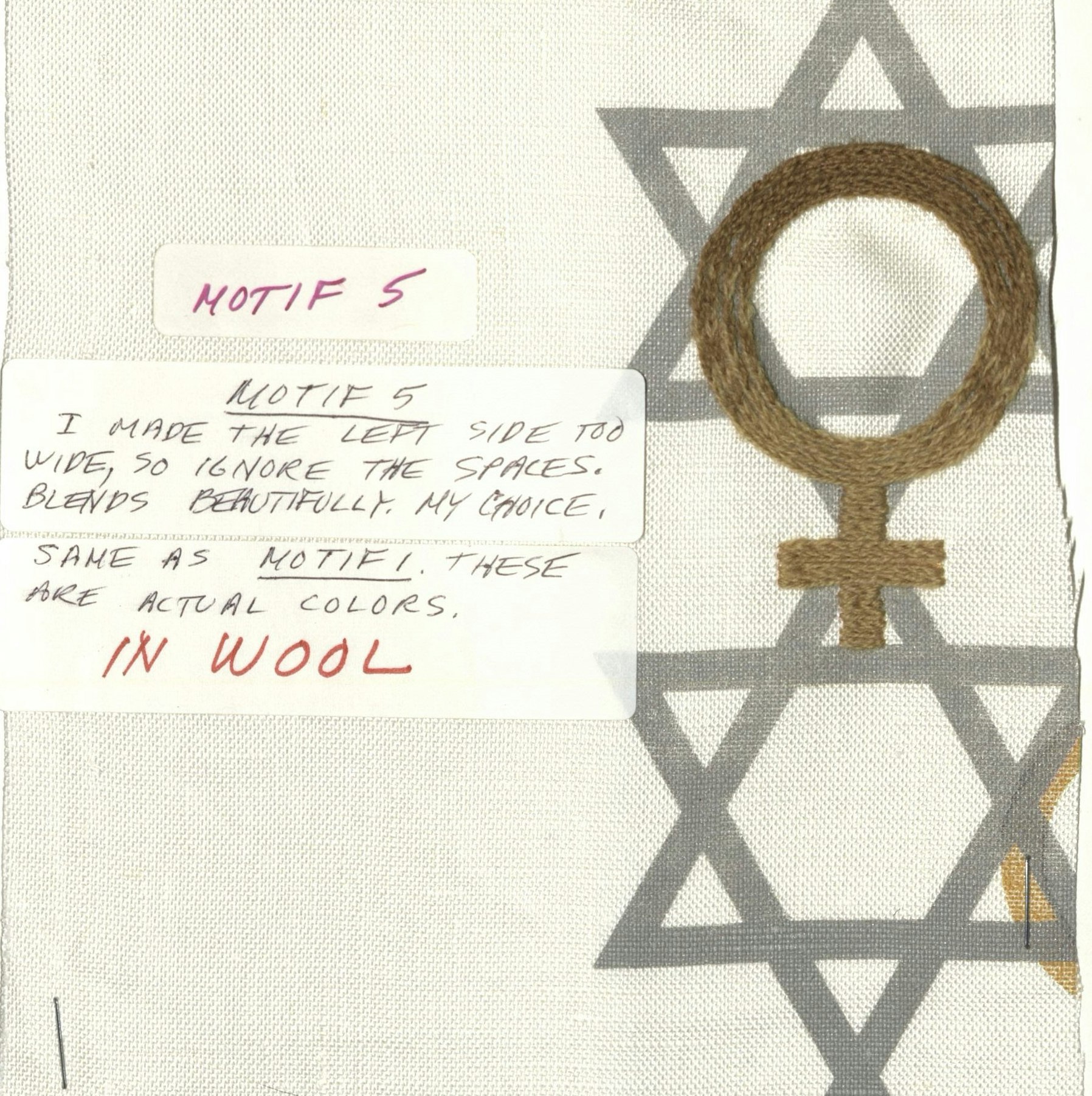

Judy Chicago collaborated with photographer Donald Woodman and several artisans for the Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light. Conceptualized and created over a period of eight years, the Holocaust Project was the culmination of Chicago and Woodman’s exploration of their Jewish heritage through extensive research and travel to Holocaust-related sites. The project drew attention to Jews and other groups targeted by the Nazis—including gays and lesbians, immigrants, political prisoners, gypsies, and criminals—while relating the Holocaust to other cases of genocide and to nuclear, environmental, and animal-rights issues.

Premiering in 1993, the Holocaust Project was a 3,000-square-foot exhibition augmented by an audio tour. The work featured several mural-sized pieces blending Chicago’s painting and Woodman’s photography, as well as The Fall, an 18-foot tapestry, and two stained-glass works, a rendering of the Holocaust Project logo of nesting triangles which introduces the exhibition and the monumental final work, Rainbow Shabbat. Intended “to stimulate dialogue that will contribute to a transformation of consciousness that may help prevent the recurrence of another Holocaust,” the Holocaust Project traveled for 10 years to both Jewish and non-Jewish institutions, and selections from the project continue to be exhibited.