In Their Own Voices: Black Women's Lives from the Archives

In Their Own Voices celebrates the power of defining oneself while highlighting the lifework and legacies of Black women whose papers are held in the Schlesinger Library. The featured collections—including those of the graphic designer Louise E. Jefferson, the civil and women’s rights activist Pauli Murray, and the educator Rebecca Primus—offer a rich array of photographs, letters, diaries, published works, and audiovisual materials, giving viewers an opportunity to listen to, view, and read about the experiences of Black women in their private and public lives.

This exhibition illuminates how both famous and everyday Black women have sustained and (re)claimed themselves in their personal lives while pursuing their intellectual, creative, and professional goals. Exhibition materials trace their commitment to one another through the establishment of sisterhoods of friendship and belonging and illustrate how these women devoted themselves to educating and empowering their communities and fighting for civil and human rights for all.

An underlying narrative of the exhibition is about the way librarians and archivists advocated for these collections to become part of the Schlesinger’s archives and ensured long-term public access to them. In Their Own Voices spans generations, as storytellers from the community—including some from the Black Women Oral History Project and current students—continue the conversations evoked by these archives. In this exhibition, Black women create their own narratives as part of this powerful and ongoing archival lineage.

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study gratefully acknowledges the Helen Blumen and Jan Acton Fund for Schlesinger Library Exhibitions for their support of this exhibition.

Exhibition curated by Petrina Jackson, Lia Gelin Poorvu Executive Director of the Schlesinger Library and librarian of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute

Schlesinger Library Exhibition Committee Members:

- Lee Sullivan, head of printed and published materials, Schlesinger Library

- Joanne M. Donovan, lead archivist, visual materials & recorded sound collections, Schlesinger Library

- Rachel Greenhaus, library assistant for published materials, Schlesinger Library

We are grateful for the contributions to this exhibition of:

- Joy Lindsay EdM ’24, Harvard Graduate School of Education

- Elyse Martin-Smith ’25, Harvard College

- Mariah Norman ’24, Harvard College

- Sophia Scott ’25, Harvard College

This exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Ruth Hill and Emilyn Brown.

Visit

Free and open to the public.

We encourage all visitors to reserve a time in advance to view the exhibition.

To place a request for a group or class tour of the exhibition, please complete this form at least 2 weeks before the date of your desired visit. Please understand that it can be difficult for us to accept requests on short notice. We will do our best to fulfill each request, but occasionally some requests cannot be accommodated, owing to scheduling or staffing constraints.

On view Monday, November 6, 2023–Friday, March 8, 2024

Monday–Friday, 9 AM–4:30 PM

This site includes selections from the exhibition as presented in the Schlesinger Library. For a full bibliography of all materials included in the in-person exhibition, with detailed citations and catalog links, please see this document here.

Dedication

In Their Own Voices: Black Women’s Lives from the Archives is dedicated to Ruth Edmonds Hill and Emilyn Brown.

Ruth Edmonds Hill (1925–2023) was a scholar, an oral historian, a storyteller, and an editor, and the first Black professional librarian at the Schlesinger Library. An iconic figure in the fields of oral storytelling and oral history research, she is perhaps most widely known for her major role as project coordinator of the Black Women Oral History Project at the Schlesinger Library, which is featured in this exhibition. Her other notable projects include oral histories of women in Cambodian and Chinese American communities, Latina women, and women in the federal government.

The archivist Emilyn Brown (1948–2023) dedicated a decade and a half to working on projects centered on Black history in New York City communities before being named an administrative fellow at Harvard University Library. She was hired as an archivist for the Schlesinger Library in 2008. In her fifteen years at the Schlesinger, Brown arranged and described numerous collections, including the papers of the surgeon and right-to-life activist Mildred Jefferson, the records of the League of Women for Community Service, and the archive of the civil rights activist Dorothy Height. Items from the latter two collections appear in this exhibition.

An Early History of African American Collections at the Schlesinger Library

It has been about ten years since the Schlesinger Library committed to intentionally prioritizing materials related to marginalized communities, including racial and ethnic minorities, but evidence of the accomplishments of Black women began entering the collections much earlier.

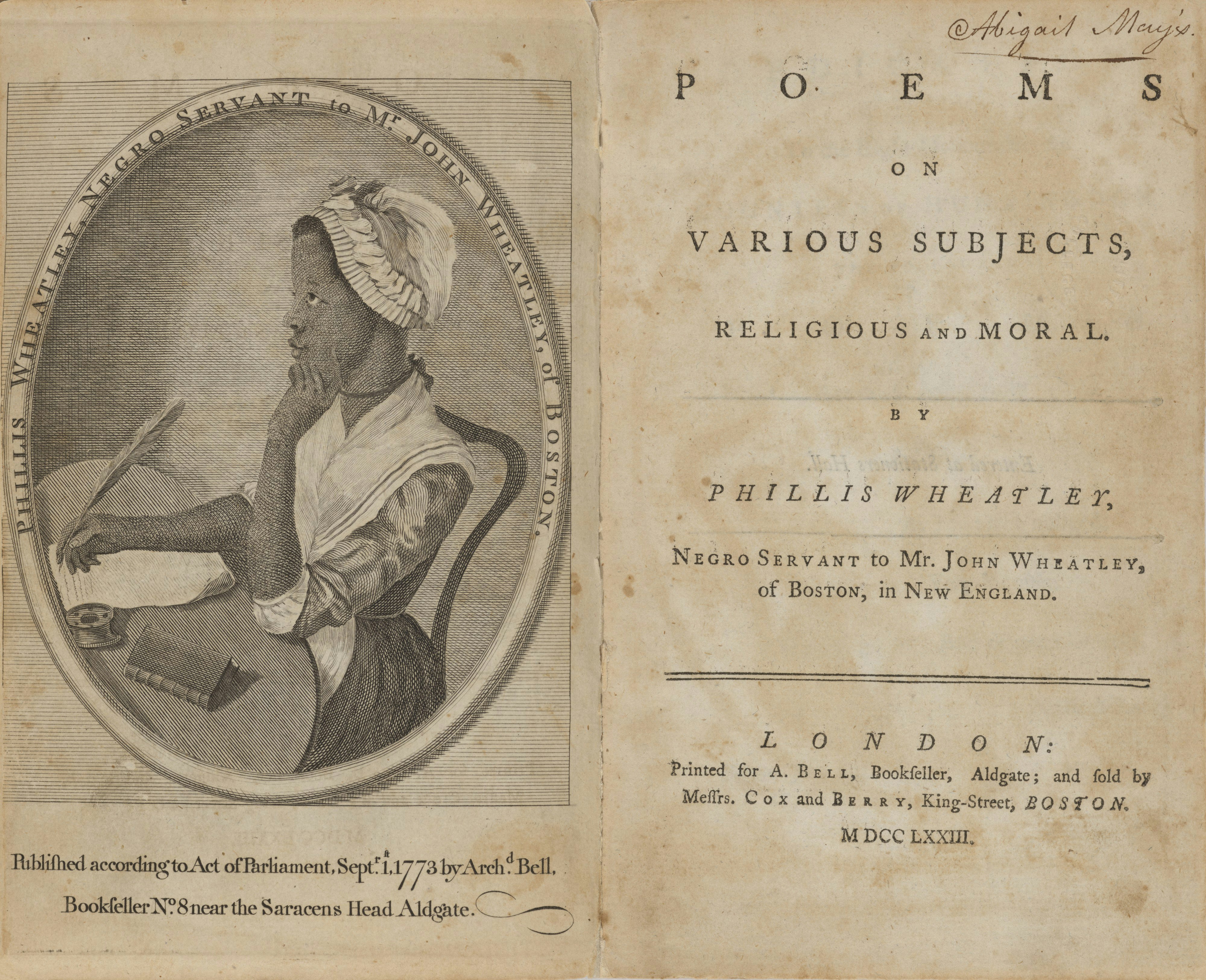

Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral came to the Library in 1905 in a bequest from the Radcliffe benefactor Sarah Wyman Whitman and was one of the first works by a Black women acquired for the collection. Born free in Africa and enslaved as a child in Massachusetts, Wheatley was America’s first Black poet and the first English-speaking person of African descent to write and publish a book.

The Papers of Roberta Church, given to the Library in 1955, were the earliest acquisition of a Black woman’s papers. Church, who was an official in the Eisenhower and Nixon administrations, donated two folders of materials documenting her career. Then, in 1964, the Library received a small set of records from the League of Women for Community Service, a group founded by Black women in Boston in 1918 that provided civic, social, educational, and charitable assistance to Boston’s Black community. These were the first Black women’s organizational records in the collection.

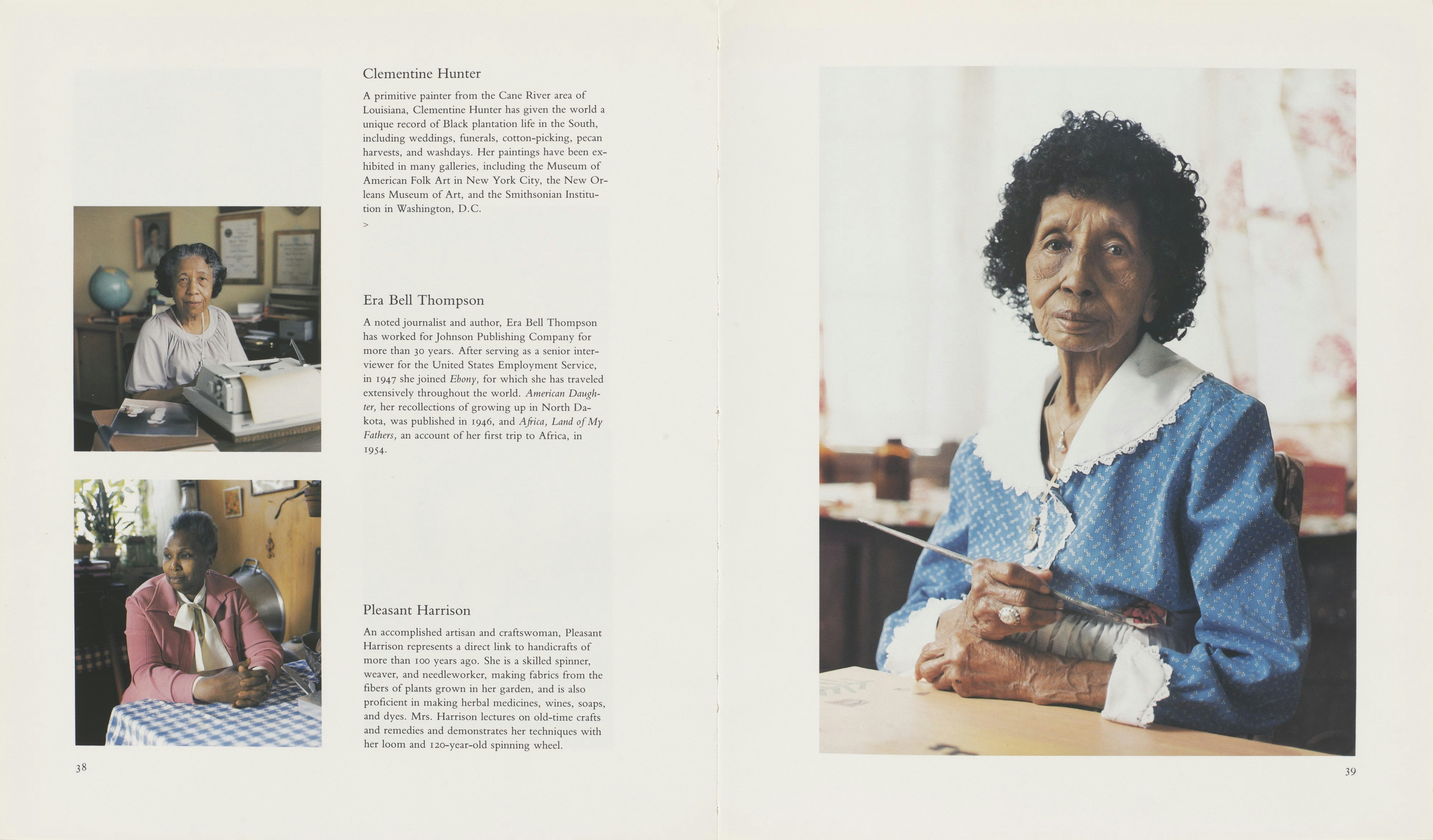

A little more than a decade later, Letitia Woods Brown, one of the first Black women to earn a PhD in history from Harvard and a member of the Schlesinger Library Council, initiated the Black Women Oral History Project (BWOHP), a landmark undertaking designed to help remedy the lack of documentation of Black women in the Library’s collections and in research libraries overall. Brown and Schlesinger Director Patricia King launched the project in 1976, identifying a cross section of older Black women from various career and life paths to take part in the oral histories. The photographer Judith Sedwick partnered with project coordinator Ruth Edmonds Hill to take portraits of many of the BWOHP participants. These portraits later became an onsite and traveling exhibition and were collected in the book Women of Courage: An Exhibition of Photographs, edited by Hill.

Today, the four collections most often requested in the Schlesinger’s reading room and visited online are the papers of Black women: the Black feminist philosopher and prison abolitionist Angela Davis; the lawyer, activist, and Episcopal priest Pauli Murray; the poet, author, activist, and professor June Jordan; and the lawyer, political activist, civil rights advocate, and feminist Florynce Kennedy. Items from the first two collections are featured in the exhibition.

Education: Rebecca Primus, Charlotte Hawkins Brown, Muriel Morisey

Education has always been an important concern for Black Americans, from enslaved people resisting anti-literacy laws to free Black people founding new schools for their communities during Reconstruction. Teaching was a profession open early to women, including Black women such as Rebecca Primus, who taught formerly enslaved students during the era of the Freedman’s Bureau, a resource that was formed after the U.S. Civil War to provide food, shelter, land, and education for the newly emancipated. About a generation later, Charlotte Hawkins Brown and other educators raised funds and established premier schools for African Americans in the Jim Crow South. In the mid-20th century, the legal segregation of schools ended, and African American women experienced many challenges trying to achieve a sense of belonging while attending universities designed neither for Black people nor for women. Some, including Radcliffe’s own Muriel Morisey, made the project of telling the story of those challenges and working to lessen the impact on later generations of students central to their life’s work.

Rebecca Primus (1836–1932)

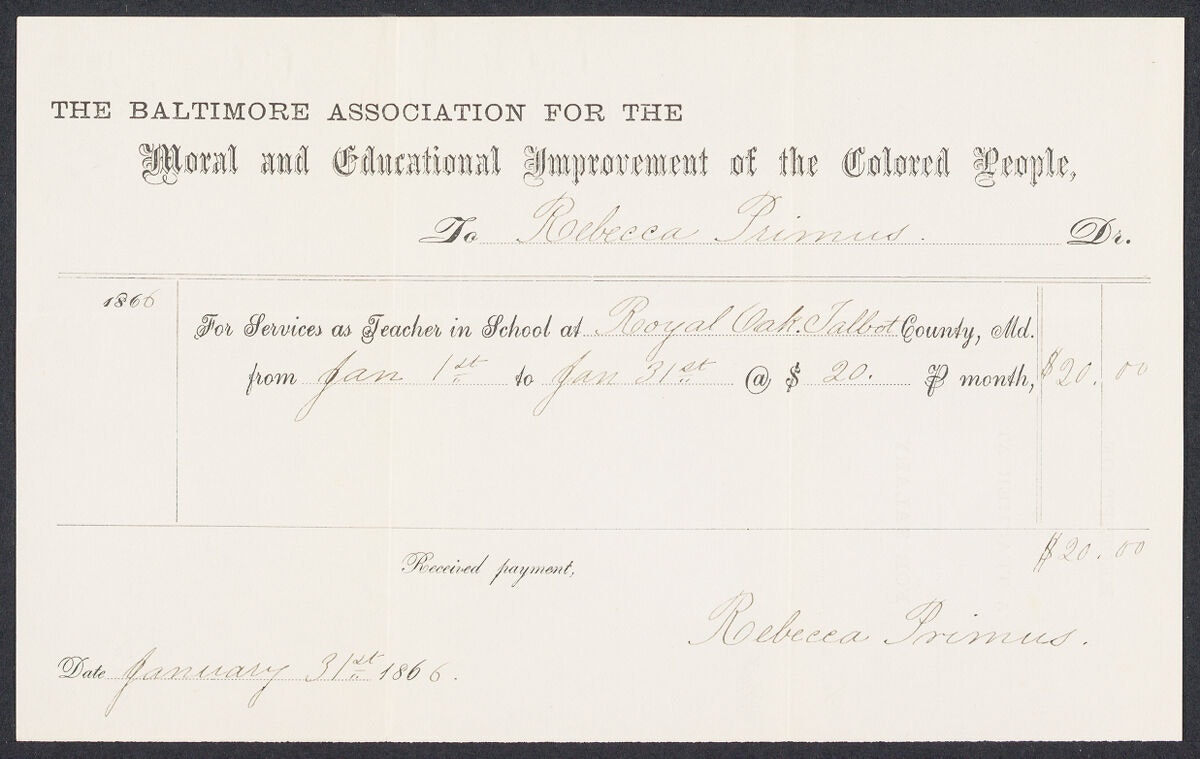

Born, raised, and well educated in Connecticut, Rebecca Primus started her teaching career in 1860 instructing local girls in her family’s home. After the end of the Civil War, she moved to Royal Oak, Maryland, under the auspices of the Freedmen’s Bureau to establish a school for newly freed African Americans in the local Black church. A receipt of her pay for that work in Royal Oak is shown here. Primus then raised funds to help build a freestanding school, which would eventually be named the Primus Institute, and taught literacy and Sunday school. She was part of a community of Black women who formed warm friendships and kept in close communication.

Charlotte Hawkins Brown (1883–1961)

Charlotte Hawkins Brown moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, as a child and excelled in school. In 1901, she accepted a position teaching Black students in rural North Carolina. After the school she was assigned to was shuttered, Brown raised money to open her own, the Alice Freeman Palmer Memorial Institute (named for Brown’s mentor, a former president of Wellesley College). The Palmer Institute was initially focused on agricultural and vocational programs and later grew into a private college-preparatory institution with a reputation as the premier boarding school for middle-class African American students. Brown led the Institute for 50 years, until her retirement in 1952. Shown here is a bulletin from the heyday of the Palmer Institute.

Muriel Morisey (1941–)

Muriel Morisey came to Radcliffe College in 1965 as part of the largest class of Black students to that date. Her experience there was punctuated by the turbulence of the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s. After graduating, Morisey worked for U.S. Congressman Walter Fauntroy and Representative Shirley Chisolm and attended law school at Georgetown University. She also held positions in the Department of Justice and at Harvard University before becoming a tenured law professor at Temple University. Her work often focuses on civil rights and equal opportunity, as illustrated by her 1986 remarks to the Association of Black Faculty and Administrators at Harvard, shown here.

Identity: Pauli Murray, Sarah Thomas Curwood, Pat Parker

Knowing and honoring yourself takes courage, especially when being true to who you are puts you in direct conflict with the expectations of family members and society or with the physical limitations of your lived reality. With the detail and precision of the trained lawyer she was, Pauli Murray bravely named and assessed her own emotions and physical symptoms when she sought out medical expertise to help her understand her gender identity. Sarah Thomas Curwood defied her husband’s insistence that she return to Boston immediately after finishing her undergraduate degree at Cornell University, choosing to stay among her friends and community until she was ready to leave in her own time. And despite her breast cancer diagnosis, the poet Pat Parker committed to fully living her best life by prioritizing her writing, healthy habits, time with family, and plans to visit dear friends, including the feminist poet and activist Audre Lorde.

Pauli Murray (1910–1985)

Pauli Murray was a lawyer, a civil and women’s rights activist, a poet, and the first African American woman ordained as an Episcopal priest. She also wrote States’ Laws on Race and Color, described by Thurgood Marshall as the “bible” for civil rights attorneys. In her legal work, Murray coined the term “Jane Crow” to describe the oppression of Black women in the post-Reconstruction era. At the same time that she was working to challenge the societal barriers that confined Black people and women in the public sphere, Murray deeply questioned her own sex and gender and spent years seeking medical guidance about her feelings of physical and mental dysphoria and exploring how to express her full identity. The 1940 “Summary of Symptoms of Upset” notes here offer one glimpse of her approach to these issues.

Sarah Thomas Curwood (1916–1990)

Sarah Thomas Curwood grew up in Binghamton, New York, and earned a bachelor’s degree from Cornell University in 1937, a master’s degree from Boston University in 1947, and a PhD from Radcliffe College in 1956. She married, had two children, and built a varied and impressive career as a sociologist, a professor, and a conservationist. Balancing the demands of a volatile marriage and her own needs and desires was challenging for Curwood, as seen here in the 1937 correspondence between her and her husband, in which she asserts her need to seek out her own happiness. Curwood was widowed in 1949 when her husband died by suicide. She continued teaching and farming into her late 60s.

Pat Parker (1944–1989)

Originally from Texas, the feminist poet Pat Parker lived most of her life in the San Francisco Bay area. After her two early marriages to men both ended in divorce, Parker began openly identifying as a lesbian and devoted her life and activism to the intersections of all her identities: Black, woman, lesbian, feminist, anti–domestic violence activist. In addition to creating poetry that was steeped in her life’s stories and radical politics, like the work in Jonestown & Other Madness (1985), Parker founded the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council and the Women’s Press Collective. She died in 1989 after a valiant battle with breast cancer. Parker wrote the letter shown here to herself after a round of cancer treatments about a year before her death. It outlines her recommitment to living life to its fullest.

Work: Anna Louise James, Gretchen Flippin Jackson, Louise Jefferson

Because of the system of chattel slavery and its long-lasting financial and social impacts on African Americans, Black women in America have almost always worked, whether in private or public spaces. Although cultural narratives for upper- and middle-class white women held that they should not work outside the home and that only some work was appropriate for women, Black women were often compelled to work, through either forced labor or economic oppression. The women in this section broke the barriers of established gender and racial norms in the workplace and chose occupations that inspired them. Among them is Anna Louise James, the first Black woman licensed as a pharmacist in Connecticut, whose family legacy was passed along to her niece Anne Lane Petry, both a registered pharmacist and a celebrated author. Also featured are the entrepreneur Gretchen Flippin Jackson, who gave literal voice to her community on Boston radio, and the designer Louise E. Jefferson, who used her artistic abilities to represent African and African diasporic culture in realistic and dignified ways in creative media.

Anna Louise James (1886–1977)

For almost 60 years, Anna Louise James, the first African American woman licensed as a pharmacist in the state of Connecticut, was a fixture in her local community. She operated James Pharmacy in Old Saybrook from 1911 until her retirement, in 1967. The pharmacy and soda fountain had a further life after her retirement and carried on her legacy, as described in the brochure shown here.

Gretchen L. Flippin Jackson (1918–2012)

In addition to owning and operating Douglass Square Pharmacy in Boston with her husband, Gretchen Flippin Jackson was an entrepreneur, a radio personality, and a journalist. She led a pioneering interracial modeling agency and was the first Black woman radio show host in Boston. Featured here is a letter Jackson wrote to the vice president of the radio station on her personalized business stationery, outlining her diverse skill set and ambition to become “a TOP WBMS Personality.”

Louise E. Jefferson (1908–2002)

The illustrator, graphic designer, and photographer Louise E. Jefferson was part of the Harlem Renaissance and a cofounder of the Harlem Artists Guild. Jefferson’s accomplished career included almost 20 years as artistic director at Friendship Press and publication of her major work, The Decorative Arts of Africa. Another of her works for Friendship Press, the illustrated map “Twentieth Century Americans of Negro Lineage,” is included here.

Activism: Ruth Batson, Angela Davis, Dorothy Height

In 1656 in Colonial Virginia, an indentured servant named Elizabeth Key Grinstead sued for and won her freedom, becoming the first woman of African descent in North America to wage a successful court battle for her emancipation. Many Black women would follow, fighting locally and nationally for their own and others’ human rights and to transform the conditions of American society by disrupting long-held oppressive norms. Those who took the path of activism were compelled by many reasons. Ruth Batson was determined to create an equitable learning environment for her three young daughters and others like them in the Boston Public Schools. Angela Davis’s future activism was shaped by the example of her parents’ civil rights work and by her exposure to violent, racist terrorism in her Birmingham, Alabama, neighborhood. The young Dorothy Height already had a strong presence in the civil rights movement when a serendipitous meeting with the legendary educator Mary McCleod Bethune connected Height to the newly formed National Council of Negro Women, an organization she later led for four decades.

Ruth M. Batson (1921–2003)

Ruth Batson relentlessly advocated for equitable schools and resources for Black children in Boston. As chair of the NAACP Public Education subcommittee, Batson presented the Boston School Committee with a formal challenge to desegregate Boston Public Schools, the text of which can be seen on this site. When the committee refused, Batson helped establish the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity (METCO), a voluntary desegregation-through-busing program started in the mid-1960s. In her later life, Batson founded the Ruth M. Batson Educational Foundation to expand educational opportunities for African-American students through grants for college tuition and support of community groups.

Angela Y. Davis (1944–)

The political activist and scholar Angela Y. Davis developed her radical consciousness through her studies in philosophy and became a member of the Communist Party in the 1960s. Because of her beliefs and activism, Davis was fired from a teaching position at UCLA in 1970. Soon after, she was charged and jailed for her alleged involvement in an armed courthouse takeover staged in support of the Soledad Brothers, but after a high-profile trial she was acquitted. In the decades since, Davis has become an outspoken advocate for prison abolition, and in 1997 she cofounded Critical Resistance, an organization devoted to that cause. A flyer for an early CR meeting is included here. Davis is currently a professor emerita at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Dorothy I. Height (1912–2010)

Dorothy Height was one of the civil rights movement’s most influential activists. In an early role at the Young Women’s Christian Association, Height helped create its Interracial Charter. Her work Step by Step with Interracial Groups was used to support race-conscious training efforts within the YWCA. Height was a co-organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom and served as president of the National Council of Negro Women for 40 years. While in that role, she also initiated the Black Family Reunion Celebration, an annual program centered on the history and cultural values of African American families, represented here by a brochure from a 1990 event.

For the Black Collective

Black women pushed to break systems of oppression while uplifting Black communities, using writing and other artistic expressions.

The Combahee River Collective statement was penned in 1977 by a group of Black woman feminists and lesbians in the Boston area writing in resistance to the racism, sexism, and classism that permeated white feminism, the civil rights and Black power movements, and white supremacy in American society. The zine version of the statement included here was created by designer Zoë Pulley for a 2021 exhibit at the Boston Center for the Arts entitled Combahee’s Radical Call: Black Feminisms (re)Awaken Boston.

The performance artist Lorraine O’Grady protested anti-Black racism and segregation in the American arts scene in the 1980s by disrupting New York City art openings as her alter ego, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire. In character, she dressed in an all-white outfit made of gloves and struck herself with a white whip woven with white chrysanthemums while reciting poems that called out racism in the art world. The series of photographs shown in the exhibition captures one such performance.

Acts of resistance like these recognize that, as the Combahee River Collective statement says: “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

Sisterhood

There is incredible power in sisterhood. Through friendship, support, empowerment, and joy, Black women have always formed emotional bonds with one another to live fully during the trials, triumphs, and routines of life.

Delta Sigma Theta is a historically Black sorority founded by 22 college women in 1913 at Howard University. Today, the sorority has 1,000 chapters worldwide, including Iota Chapter in Boston. The exhibition includes selections from a 1943 scrapbook put together by early members of the Boston Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority.

The organization Girlfriends was founded in Cambridge, Massachusetts, by Nancy Pleasant in 1992 as a peer support group for lesbians and bisexual women of African descent. The group sponsored events, published a newsletter, and facilitated other connections among queer Black women in the area to provide a safe, accepting place for their community.

The Sister Soldier Project was founded in 2006 by Myraline Morris Whitaker to meet the needs of African American woman soldiers serving in Iraq, Kuwait, and Afghanistan, who had a hard time finding personal hygiene and hair care products during their deployments. Sister Soldier shipped more than 7,000 care packages to soldiers from 2006 to 2012. The impact of this project is reflected in hundreds of thank-you letters written by the recipients of those care packages over the years.

Archival Lineages

We invited students from Harvard University to engage with archival items from In Their Own Voices, namely the Iota Chapter scrapbook from the Records of the Boston Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and the “Summary of Symptoms of Upset” document and related newspaper clippings from the Papers of Pauli Murray. Four talented students answered the call and contributed these original, creative works in conversation with their archival foremothers/parents: Joy Lindsay (Harvard Graduate School of Education ’24), Elyse Martin-Smith (Harvard College ’25), Mariah Norman (Harvard College ’24), and Sophia Scott (Harvard College ’25).

Joy Lindsay (Ed.M. ’24) conducts community-based research that explores how school and work experiences help shape the identity and leadership development of women and girls, particularly those of African descent. She is a 2023 Adrian Cheng Fellow at Harvard Kennedy School, the founder and CEO of Butterfly Dreamz, Inc., and a proud member of the North Jersey Alumnae Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.

Elyse Martin-Smith (A.B. ’25), concentrating in Social Studies and African & African American Studies, explores questions of intersectional Black identity and the creative pursuit of justice. She serves as Vice President of Harvard BlackCAST, the Political Action Chair of the Black Students Association, and a student worker with the Law, Education, and Justice team and the Emerging Leaders Program, both at Radcliffe. She is passionate about restorative justice, prison justice, and the intersection of art, activism, and academic research.

Mariah M. Norman (A.B. ’25) is from Cincinnati, Ohio, and is concentrating in History and Literature with a secondary field in Art, Film, and Visual Studies. They are a multi-disciplinary artist, archivist, and producer; they are inspired by their mother’s role as a charter member of the Rho Theta Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.

Sophia Scott (A.B. ’25) is concentrating in Human Evolutionary Biology with a secondary field in Global Health & Health Policy. Originally from Los Angeles, California, she is a reporter and photographer for The Harvard Crimson, director of advocacy for Harvard Undergraduate Black Health Advocates, and a volunteer mentor for Boston-area children living with sickle cell disease.