Rewrite, Organize, Remix: Visions of Feminist Organizing

Shouts of struggle echo through the Schlesinger Library’s collections. Rewrite, Organize, Remix: Visions of Feminist Organizing presents dynamic stories from the archive of groups that mobilized to name and challenge injustice. Over generations, community organizers, artists, students, and thinkers have come together to voice their opposition to oppression, raising banners high for liberation. They gathered in basements, on park benches, and in cafés to discuss strategies for advancing civil rights, nuclear disarmament, and sex workers’ rights; preventing domestic violence; organizing labor; and including queer voices.

In the words of the African American feminist lesbian poet Pat Parker, revolution is ongoing: “It’s not neat or pretty or quick. It is a long, dirty, painful process.” This exhibition illustrates how people convened; learned about and articulated unique terminologies to define their selves and experiences; and created networks of allies for economic support and social capital.

Woven throughout are words of love, actions of solidarity, disagreements, and moments that sustained people through times of sorrow. Linger with the letters, pamphlets, flyers, newsletters, notes, and ephemera that mark the past and comment on the present while you contemplate what these struggles—through arguments, laughter, and revelation—inspire you to do next.

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study gratefully acknowledges the Helen Blumen and Jan Acton Fund for Schlesinger Library Exhibitions, which is supporting this exhibition.

Exhibition curated by Mimosa Shah, associate curator

Schlesinger Library Exhibition Committee Members:

- Paula Aloisio, archivist and metadata specialist

- Zachary Maiorana, librarian/archivist for digital programs

- Ellen Shea, associate director, Schlesinger Library

- John Jayo, executive assistant, Schlesinger Library

Visit

Free and open to the public.

Registration is recommended. Each reservation grants entry for the individual named in the confirmation only. Please make a separate booking for each member of your party.

To place a request for a group or class tour of the exhibition, submit this form at least two weeks before the desired date of your visit. Please understand that it can be difficult for us to accept short-notice requests. We will do our best to fulfill every request, but owing to scheduling or staffing constraints, some requests cannot be accommodated.

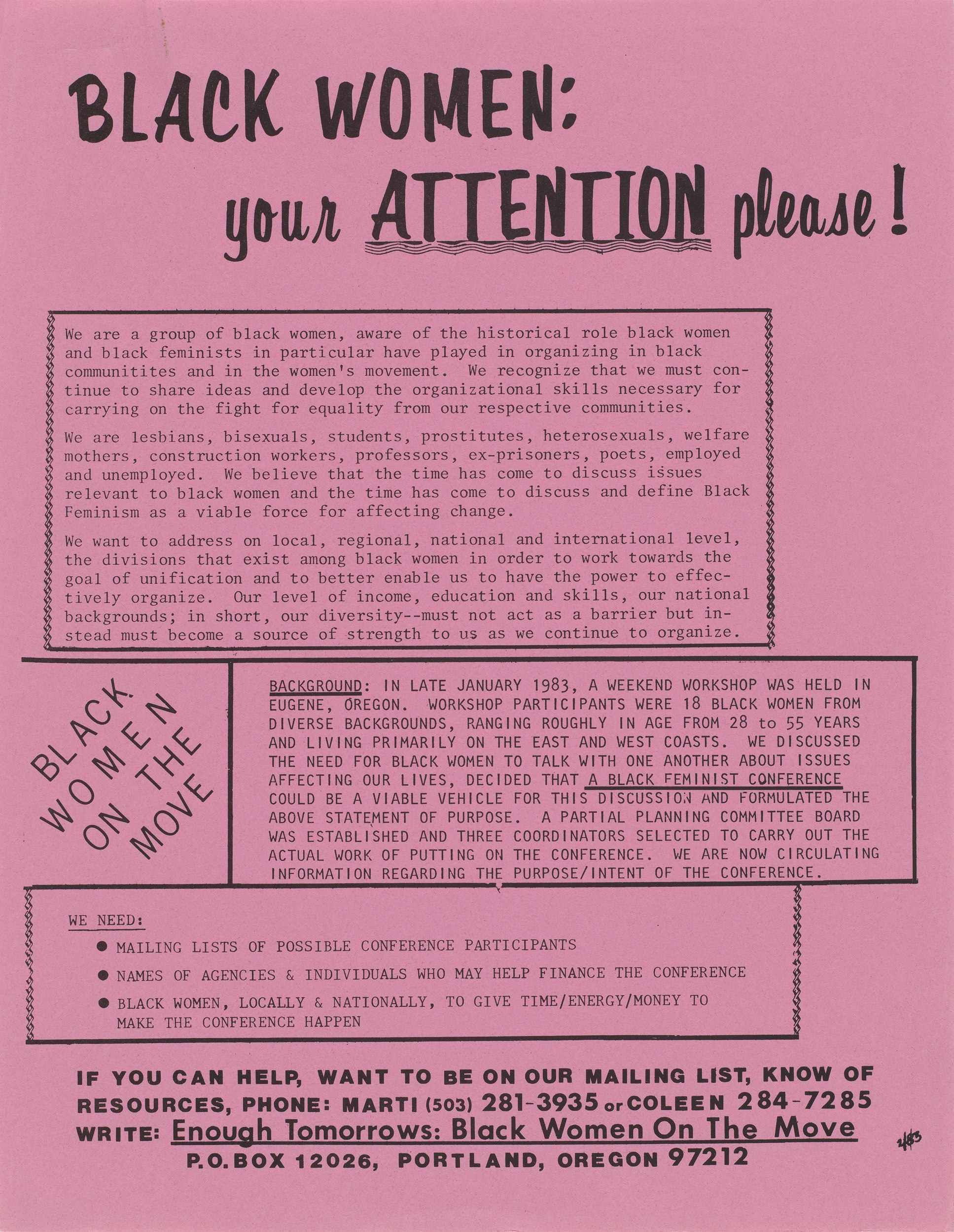

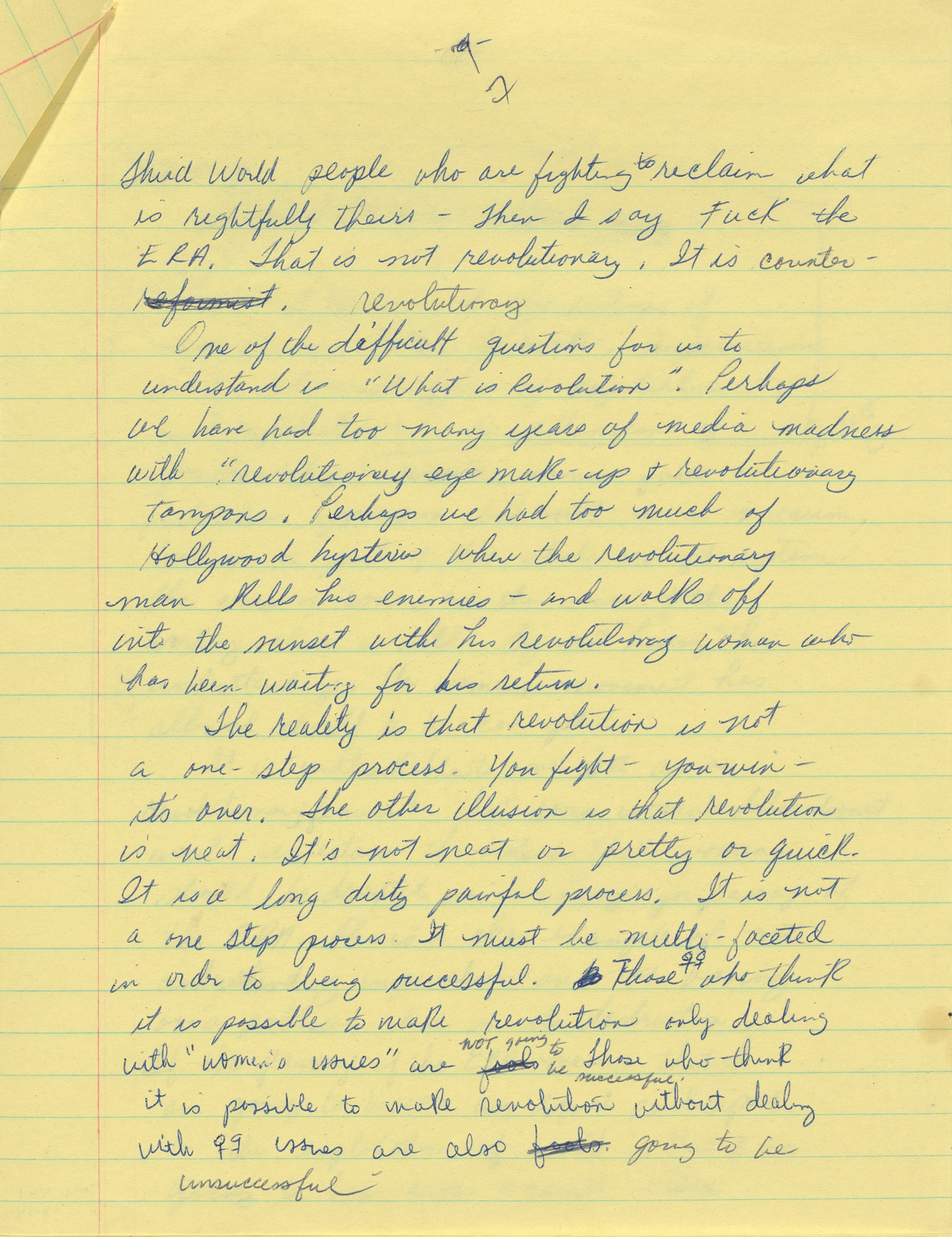

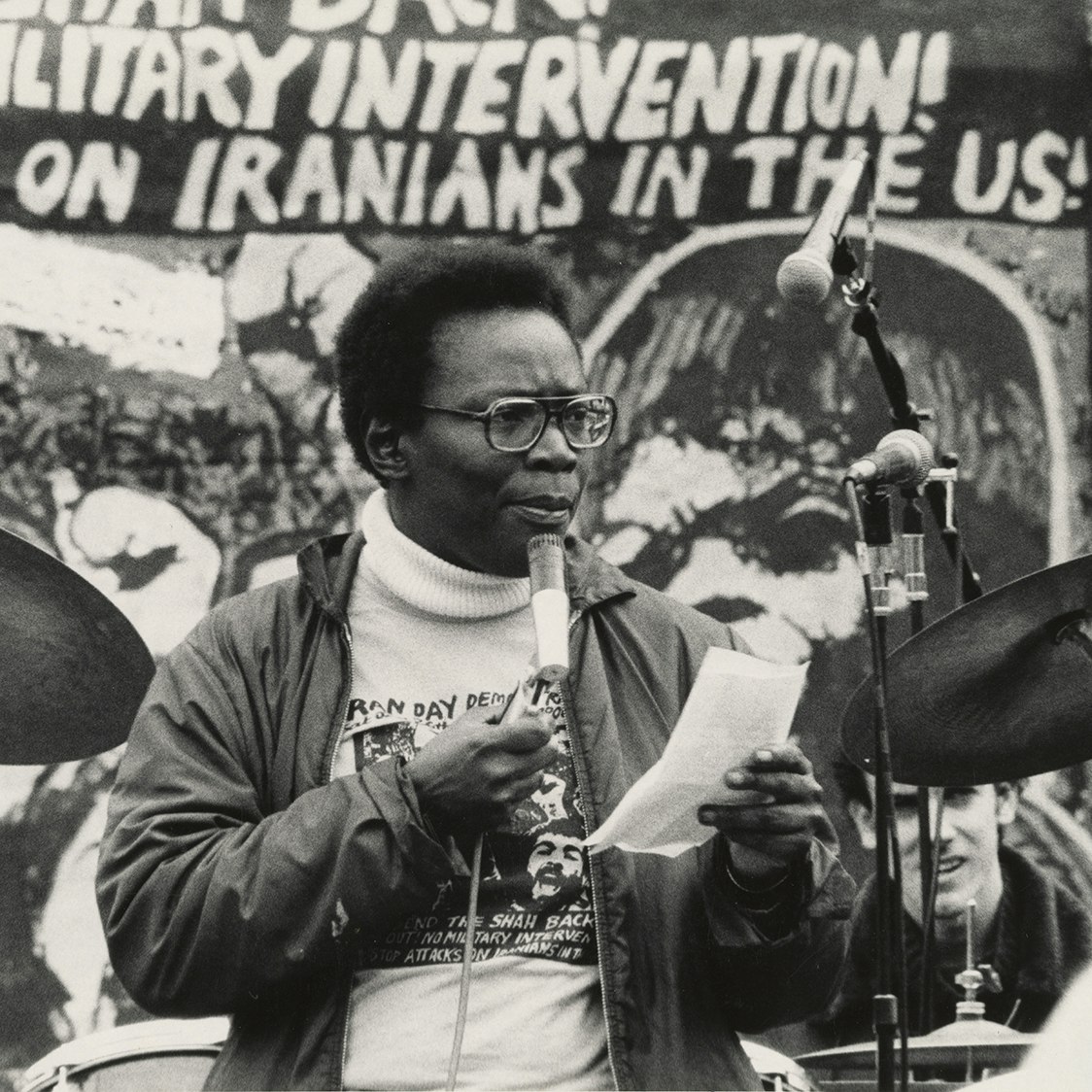

Talking about a Revolution: Pat Parker and Theories of Social Change

How do we effect social change? Throughout the library’s collections, we see individuals and organizations that came together to visualize and act on the desire for a more just society. Yet working toward liberation requires more than imagining freedom. To paraphrase Pat Parker, organizing and activism involve the recognition that revolution takes place over multiple (and cyclical) phases. A Black woman, a lesbian, and a poet, Parker emphasized the need for feminist movements to address the broad lived experiences of those who fight for change. These drafted speeches from the 1980s are testimonials to contemporary consciousness-raising efforts that sought to bridge differences while highlighting previously elided voices. The First Black Lesbian Conference of 1980 grew out of the First National Third World Lesbian and Gay Conference, held in Washington, D.C. in 1979, and addressed the sexism, racism, and homophobia that African American lesbians endured while celebrating the joy of one another’s presence.

“The reality is that revolution is not a one-step process. You fight—you win—it’s over. The other illusion is that revolution is neat. It’s not neat or pretty or quick. It is a long, dirty, painful process. It is not a one-step process. It must be multi-faceted in order to be successful. Those women who think it is possible to make revolution only dealing with ‘women’s issues’ are not going to be successful. Those who think it is possible to make revolution without dealing with women are also going to be unsuccessful.”

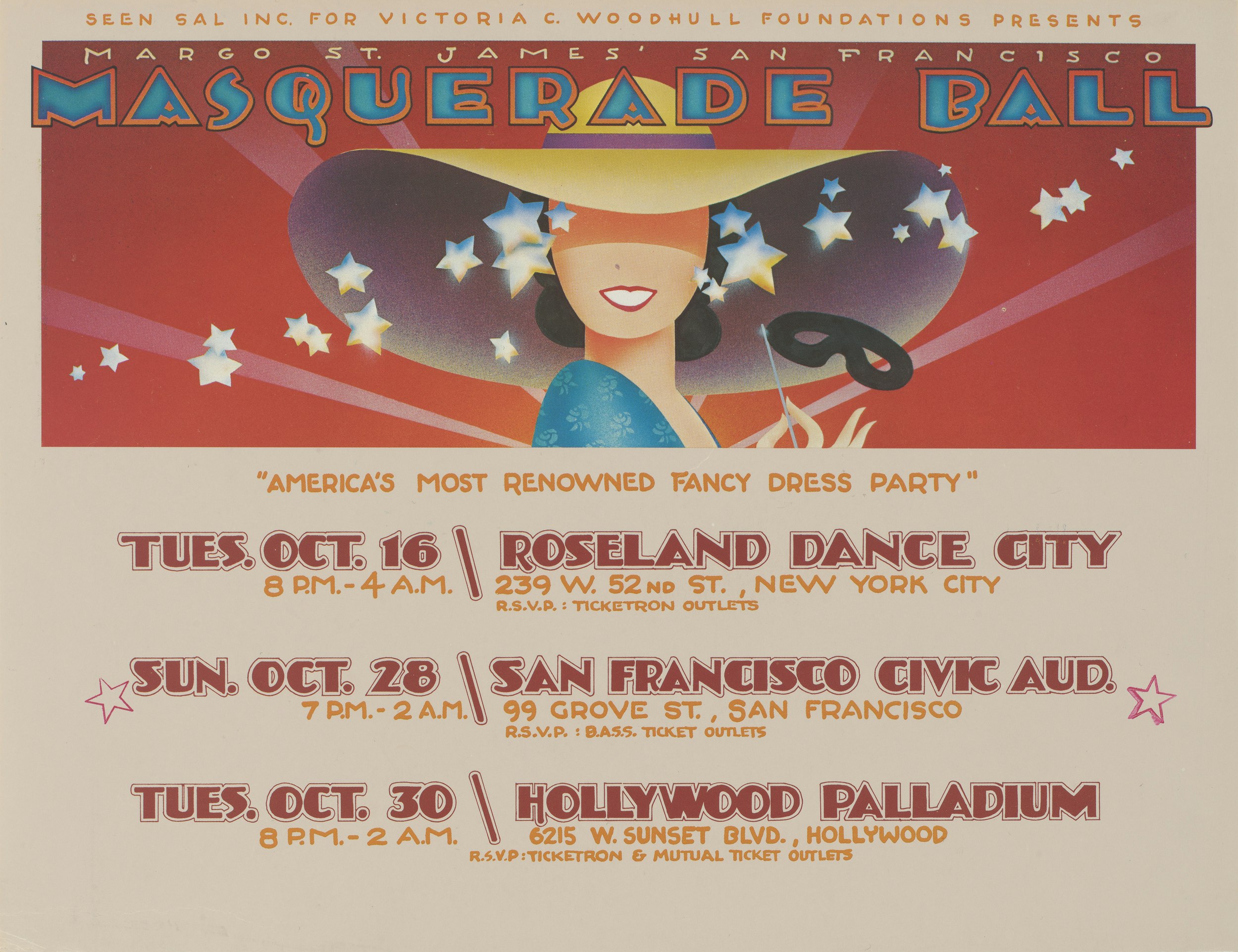

Co-Conspirators Color the Night

Founded in San Francisco in 1973, Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics (COYOTE) provided social services and support for sex workers. COYOTE’s founder, Margo St. James (1937–2021), strove to promote sex-positive feminism. Many feminists were at odds with the National Organization for Women (NOW), underscoring the need for radical decentralization. Sex workers were often excluded from mainstream feminist movements. Working toward civil rights for sex workers, COYOTE campaigned for the decriminalization of sex work and provided health and legal services to sex workers. The organization and its many chapters worked to remove the stigma surrounding female sexuality. Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, COYOTE partnered with the Victoria C. Woodhull Foundation, which sought to decriminalize sex work while tackling issues related to sexual violence, reproductive rights, and welfare. Fundraising efforts through the annual Hooker’s Masquerade Ball were sprawling events surfacing the call for freedom to live life on one’s own terms.

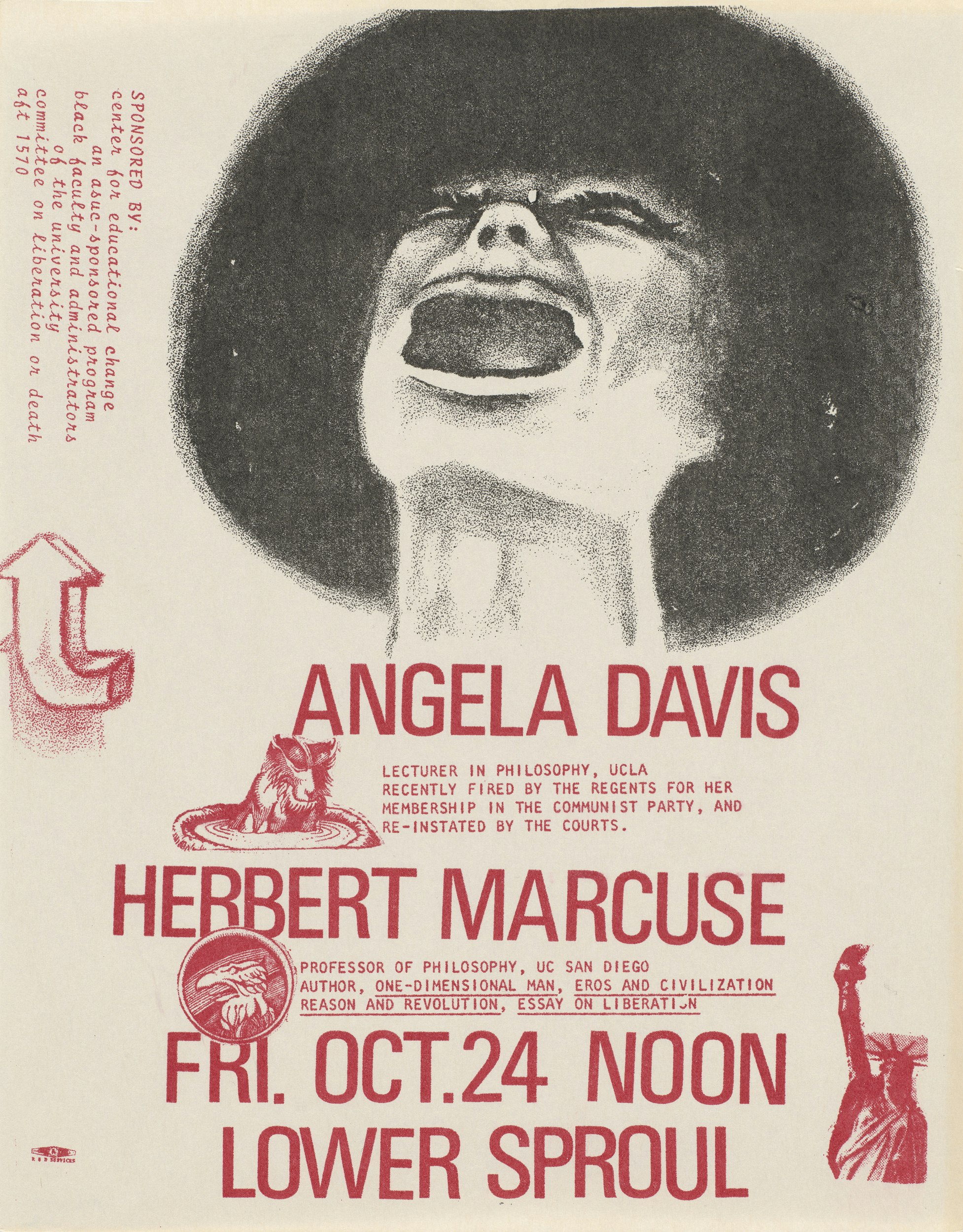

The Many Forms of Feminist Resistance

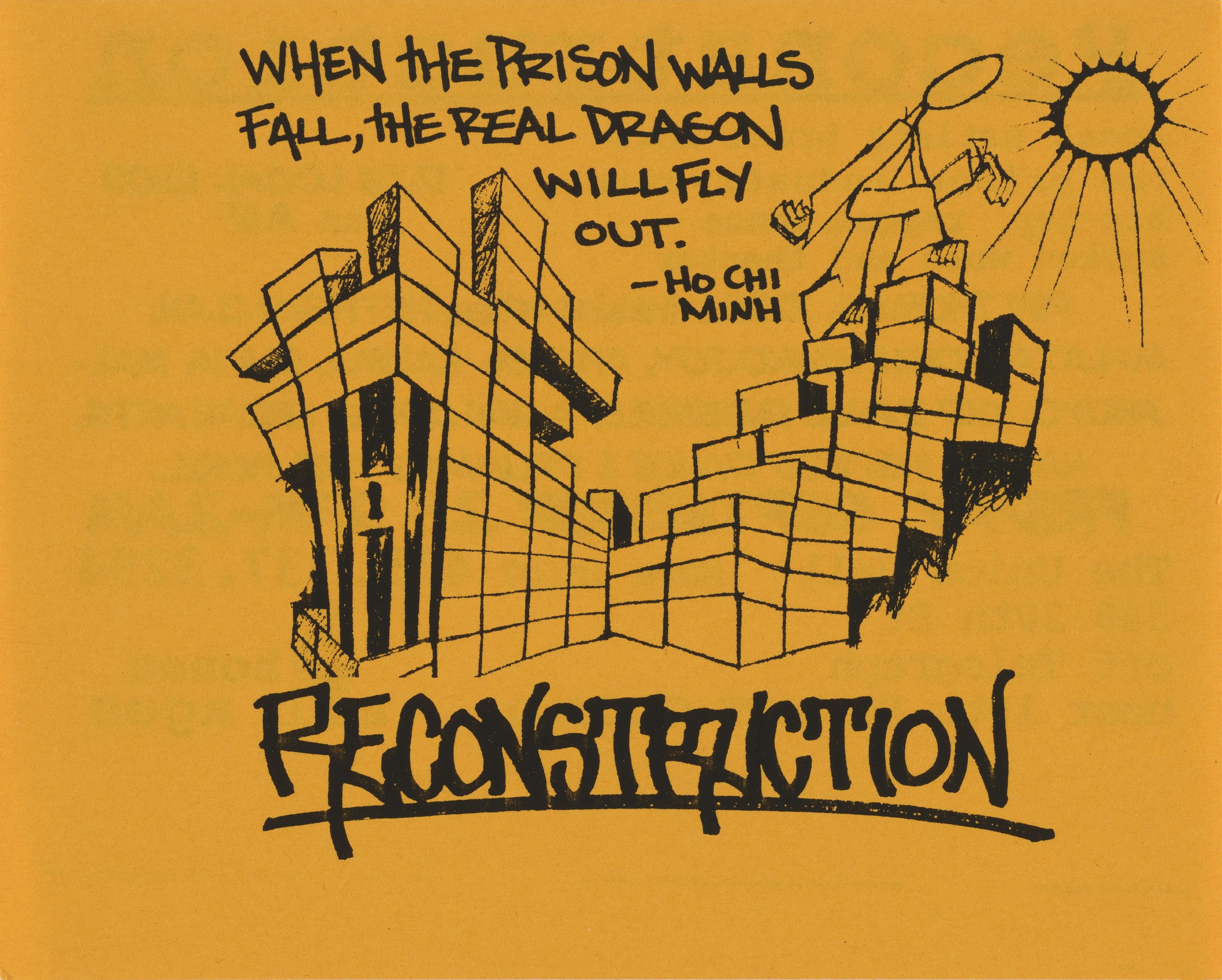

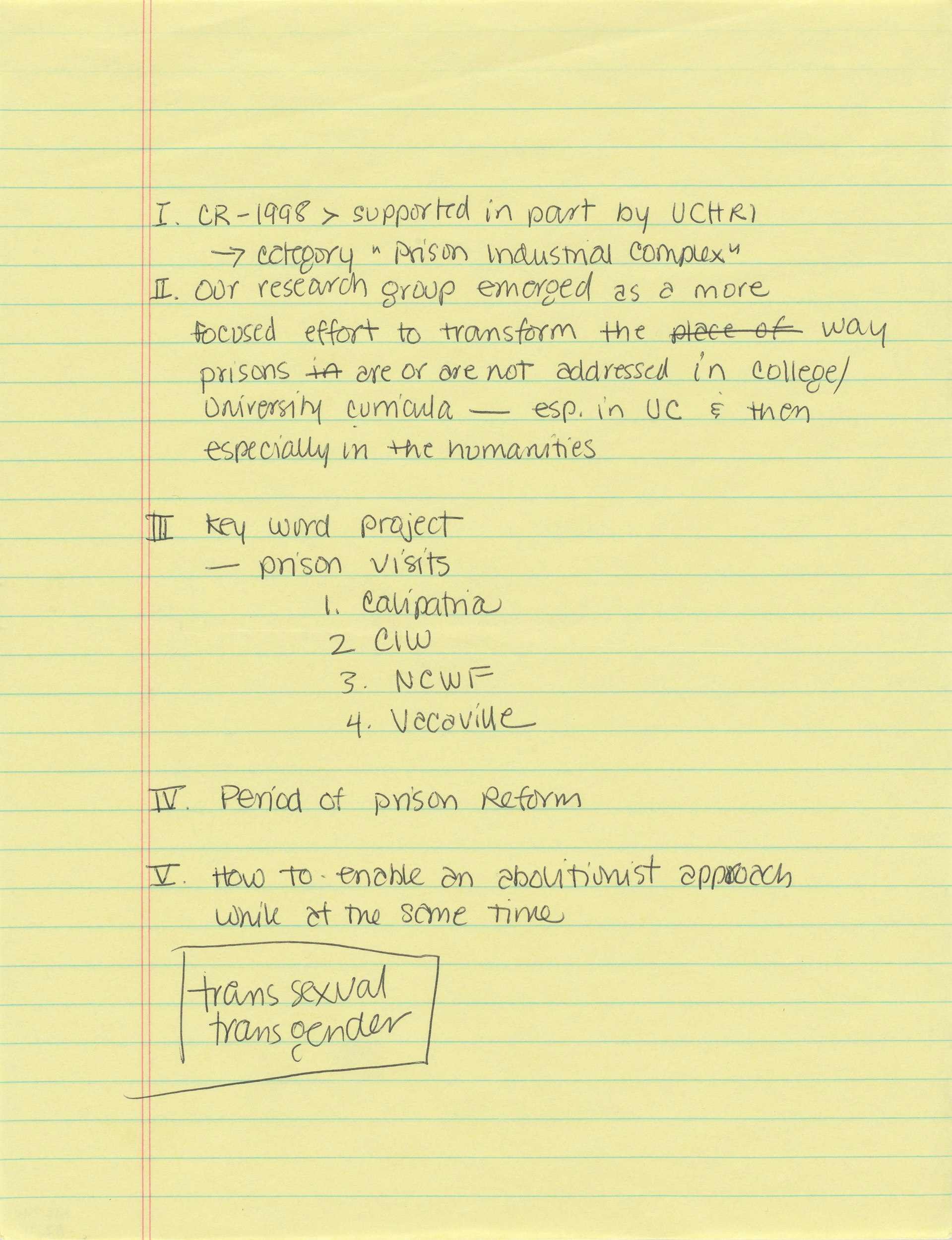

Working toward lasting structural change collided with the realities of powerful government bodies throughout the 1960s and beyond. The scholar, author, and Black feminist philosopher Angela Y. Davis was prosecuted for purchasing firearms used in the takeover of a California county courtroom; she persisted through a famous trial and ultimately won acquittal in 1972. Twenty-five years later, Davis and others co-founded the organization Critical Resistance with the goal of dismantling the prison-industrial complex. Davis’s activism exemplifies how feminists connect personal experiences of sexism, racism, and bigotry to larger issues of oppression. The first Critical Resistance conference, in 1998, brought together activists, formerly incarcerated persons, academics, and others to strategize ways to organize the prison-abolition movement. The conference also provided an opportunity to build solidarity among individuals of diverse backgrounds. Critical Resistance’s model of organizing both annual national conferences and periodic regional teach-ins, symposia, rallies, demonstrations, and celebrations is echoed in the tactics of parallel movements.

Seeking Sanctuary While Building Solidarity in the Streets

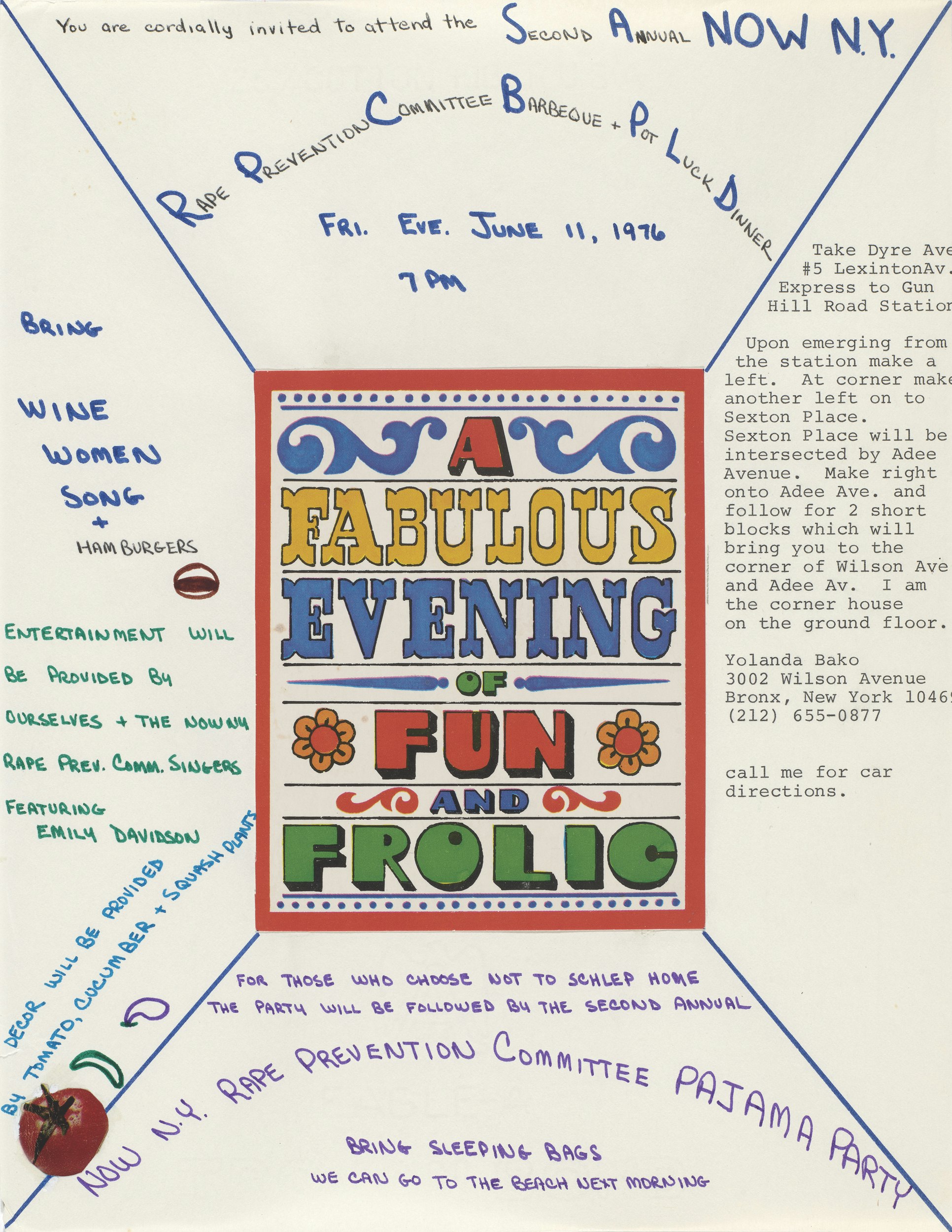

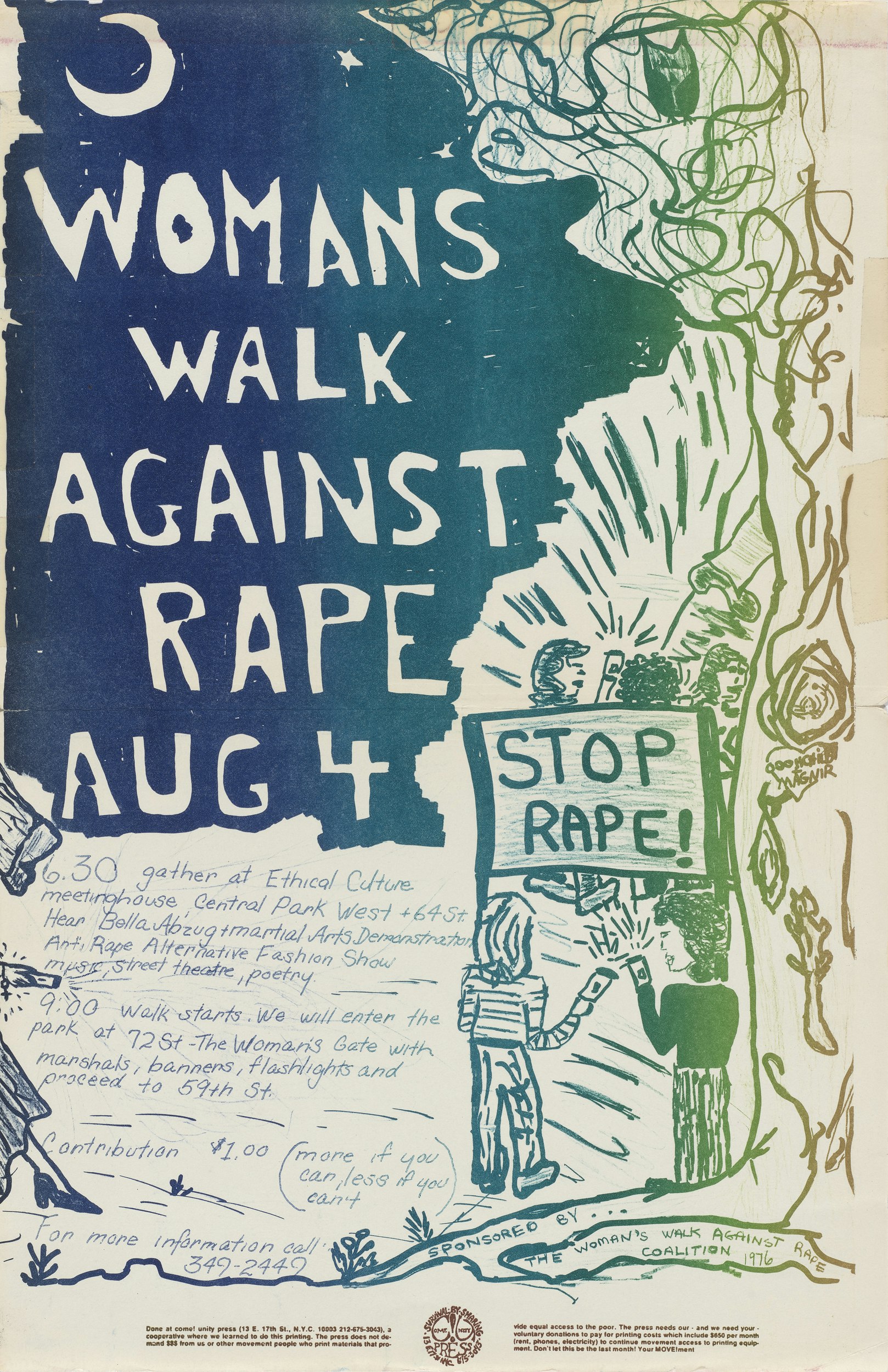

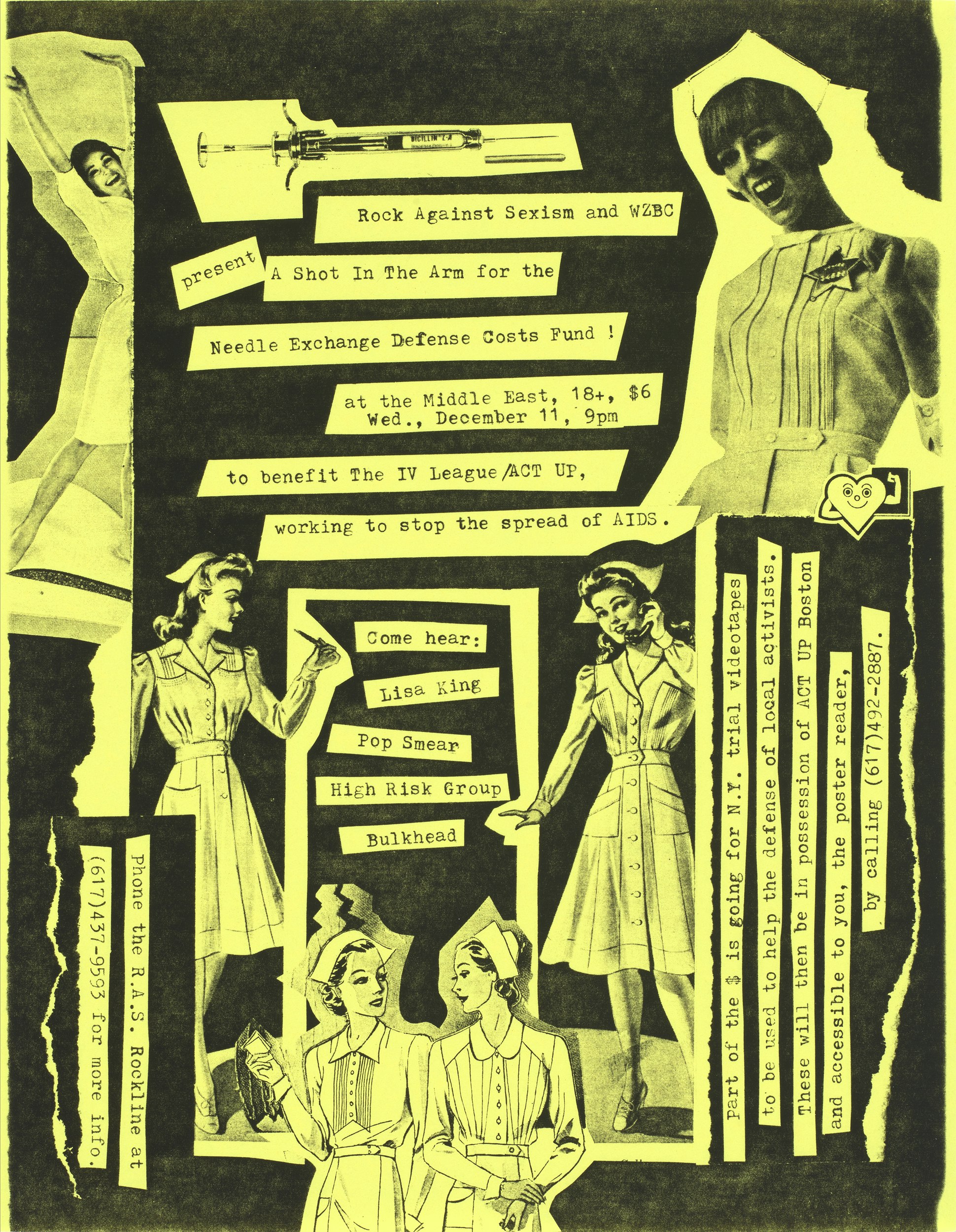

Gender-based violence-prevention efforts gained momentum during the 1970s and beyond. Yolanda Bako co-founded the first shelter for battered women in New York City, and later served as coordinator of the Rape Prevention Committee for the city’s National Organization for Women (NOW) chapter, which sponsored the 1976 Women’s Walk Against Rape. Efforts to create legislation to prosecute abusers coincided with efforts to coordinate care and support for survivors striving for independence. Through her work with NOW, Bako sought to build coalitions while underscoring that no one suffered alone. Flyers and posters for picnics, marches, and protests illustrate these often-joyous manifestations, including one hosted at Harvard with the poet June Jordan. Rock Against Sexism, a political and cultural movement that challenged misogyny in punk and other music scenes, sponsored spaces promoting women artists and benefiting the HIV/AIDS activist group ACT UP. Indeed, the collective call to take back the night remixes words once penned furtively, asserting that anything worth doing should be done in community.

Making Space: Zines as a National Platform

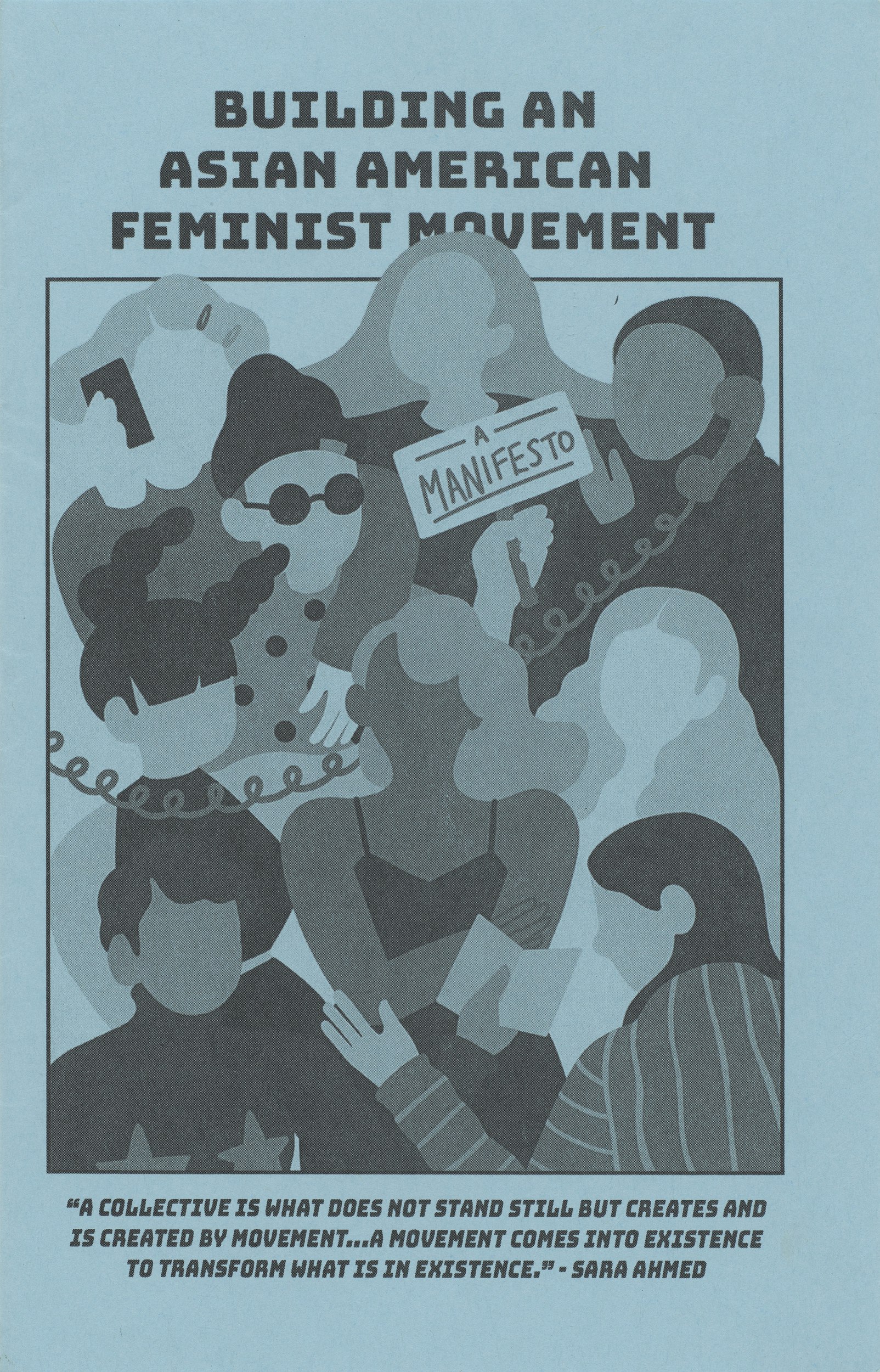

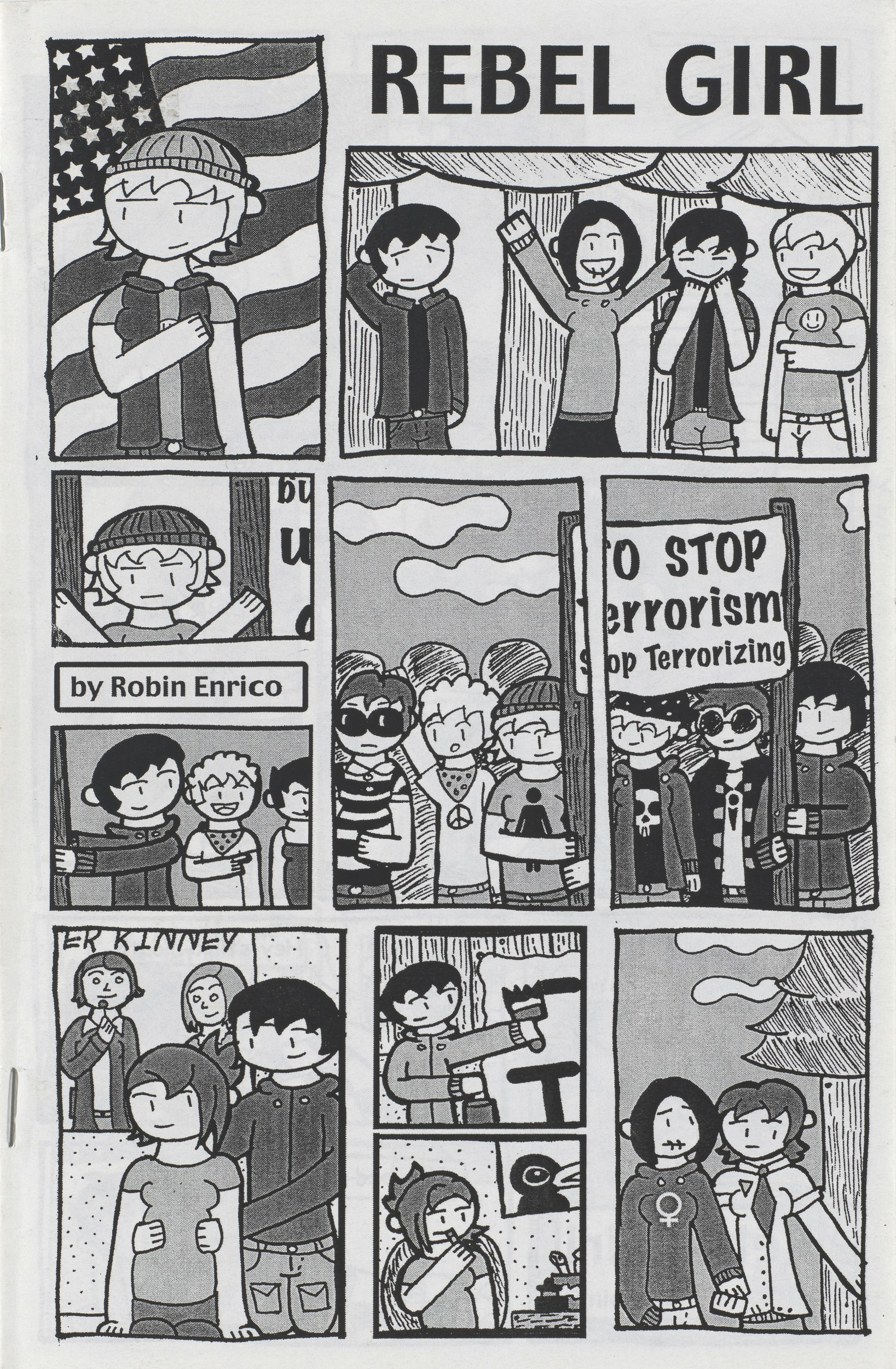

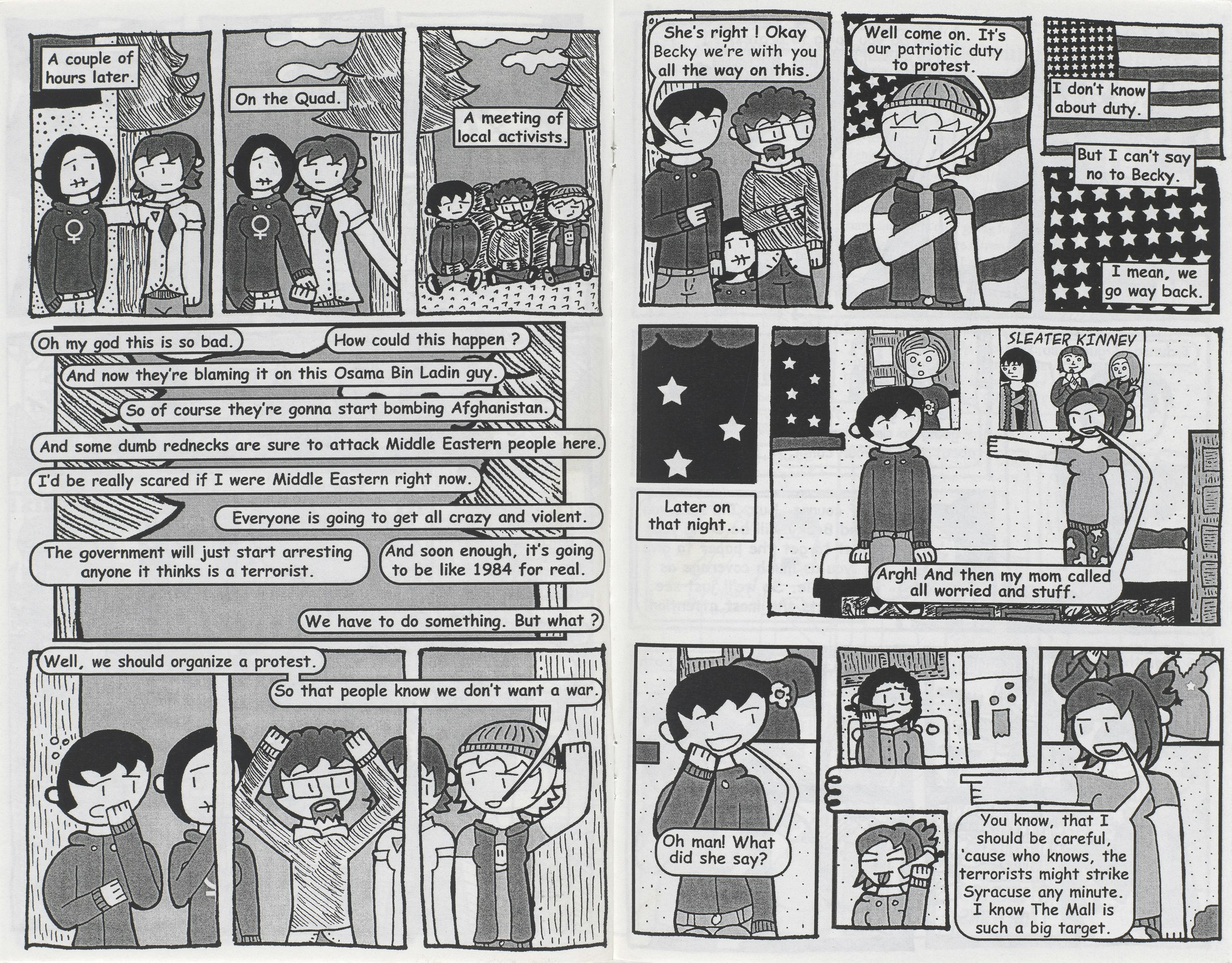

Starting in the late 1980s, zines—small-batch, noncommercial, self-published works—emerged, documenting messages of feminist activism like newsletters of yore but with a more localized network. Girl Germs, spawned by the Riot grrrl movement, an underground feminist network that started in Olympia, Washington, combines punk music, politics, and female empowerment. Collaged, copied, folded, and stapled, these pages found their way into mailboxes, bookstores, and record stores across the country. Their messages reverberate long after the first print run ended. Nearly thirty years later, the Asian American Feminist Collective (AAFC) was formed in New York City during the aftermath of the 2017 Women’s March. AAFC’s zines take inspiration from the 1977 Combahee River Collective statement by Black socialist feminists, which is referenced in the zines’ pages. The emphasis is on seeking to uplift the multi-dimensional ways Asian Americans confront systems of power.

Fifteen Years of Sustained Feminist Organizing

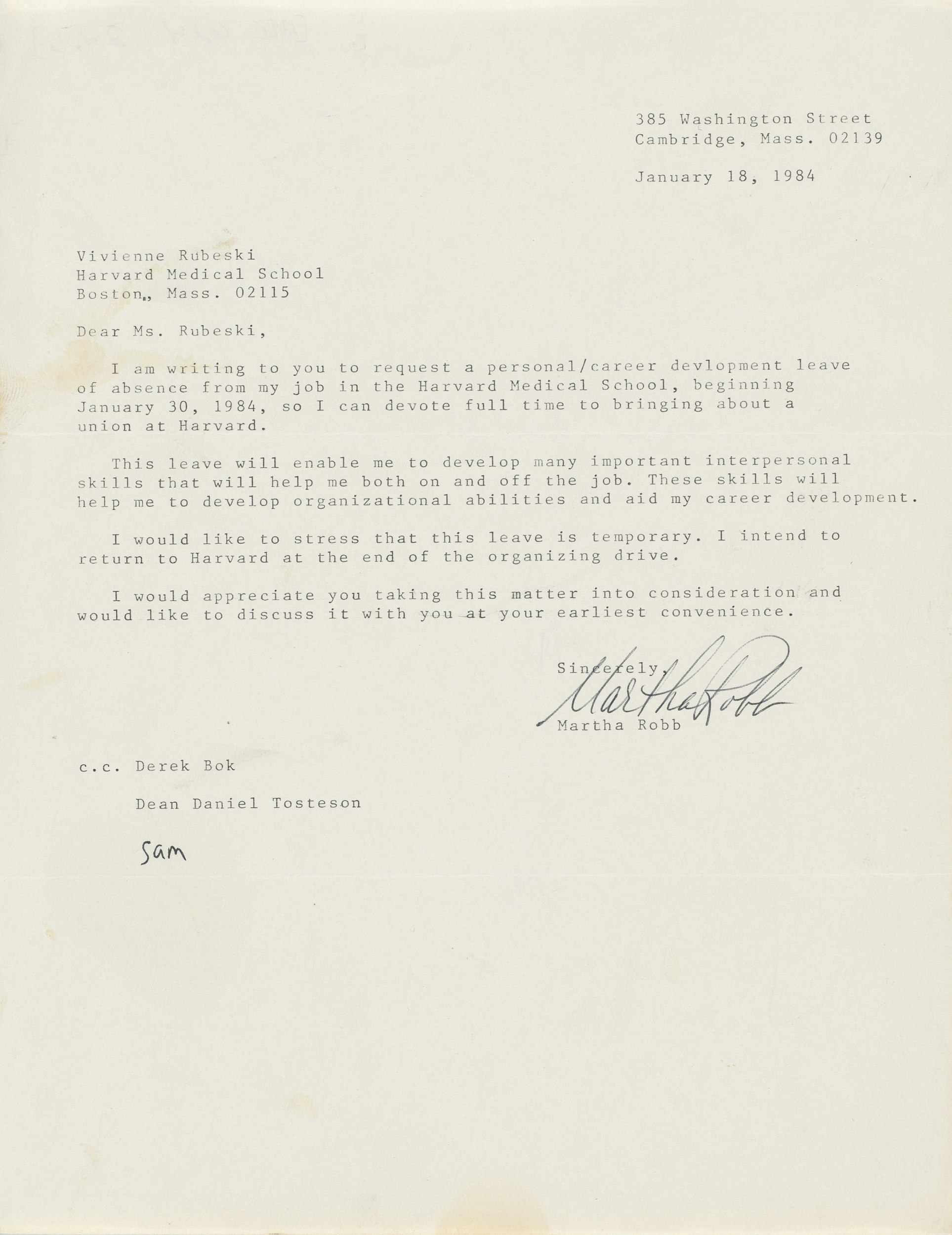

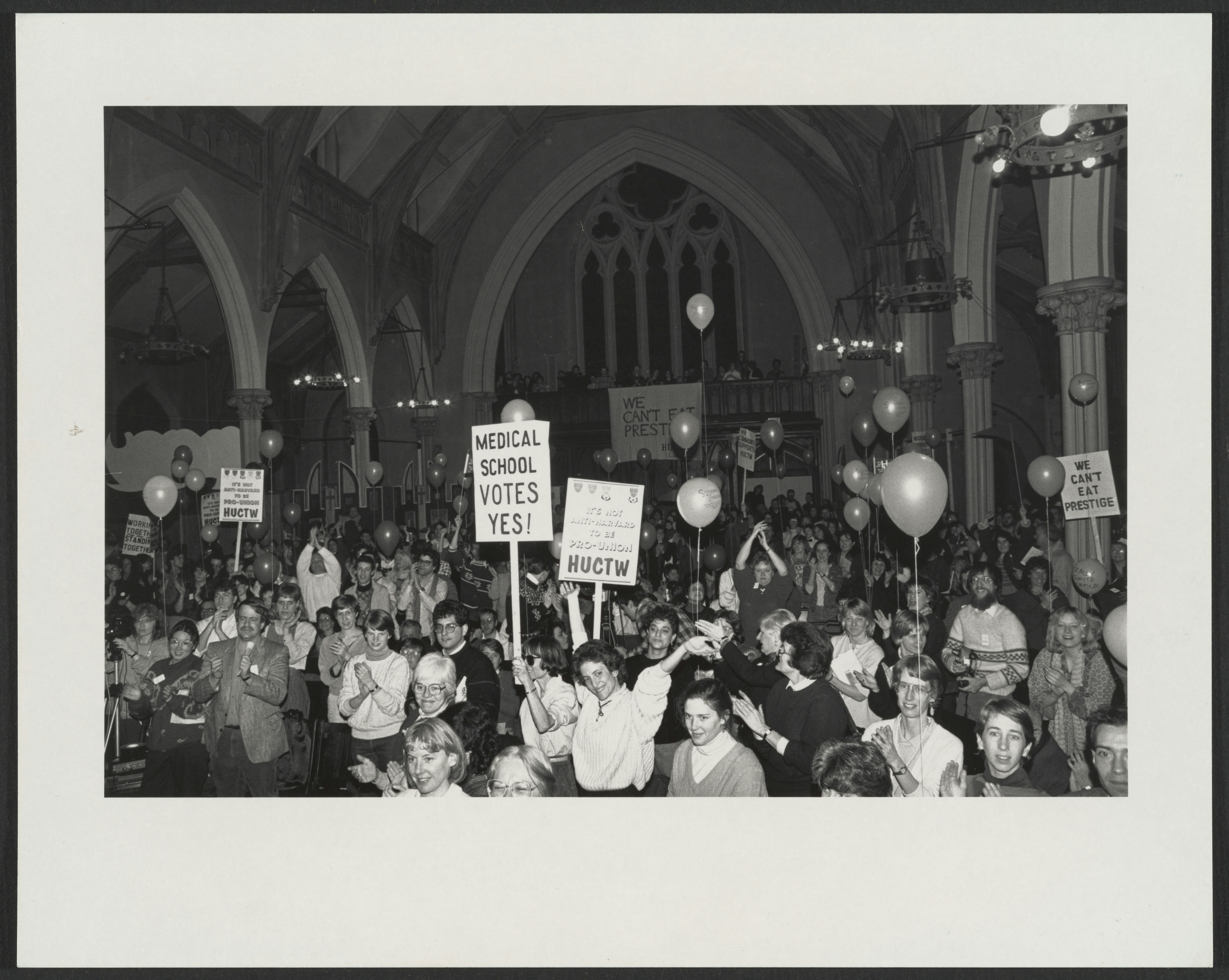

Labor organizing intersected with feminist activism during the 15-year campaign to officially recognize the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers (HUCTW). Seeds of HUCTW’s founding were planted in the early 1970s, when a group of women research assistants, graduate student workers, and faculty members at Harvard Medical School met to fight against poor workplace conditions, low pay, and sexism. Their efforts eventually led to organizing on behalf of all university clerical and technical staff. In 1984, the lab assistant Martha Robb wrote to her supervisor to request leave to commit to grassroots organizing efforts; hers is one of many similar letters in the HUCTW collection at the Schlesinger. Flyers, buttons, and stickers are some of the ephemera that document the decades of organizing that resulted in a triumph for Harvard workers. On May 17, 1988, nearly 3,400 university employees across six campuses—82 percent of whom were women—voted to be formally represented by HUCTW, an affiliate of the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). The slogan “We Can’t Eat Prestige” resonates to this day, harking back to the legacy of the 1912 “Bread and Roses” strike for fair pay and dignity by textile workers in Lawrence, Massachusetts.

Shared Struggles and Dissent

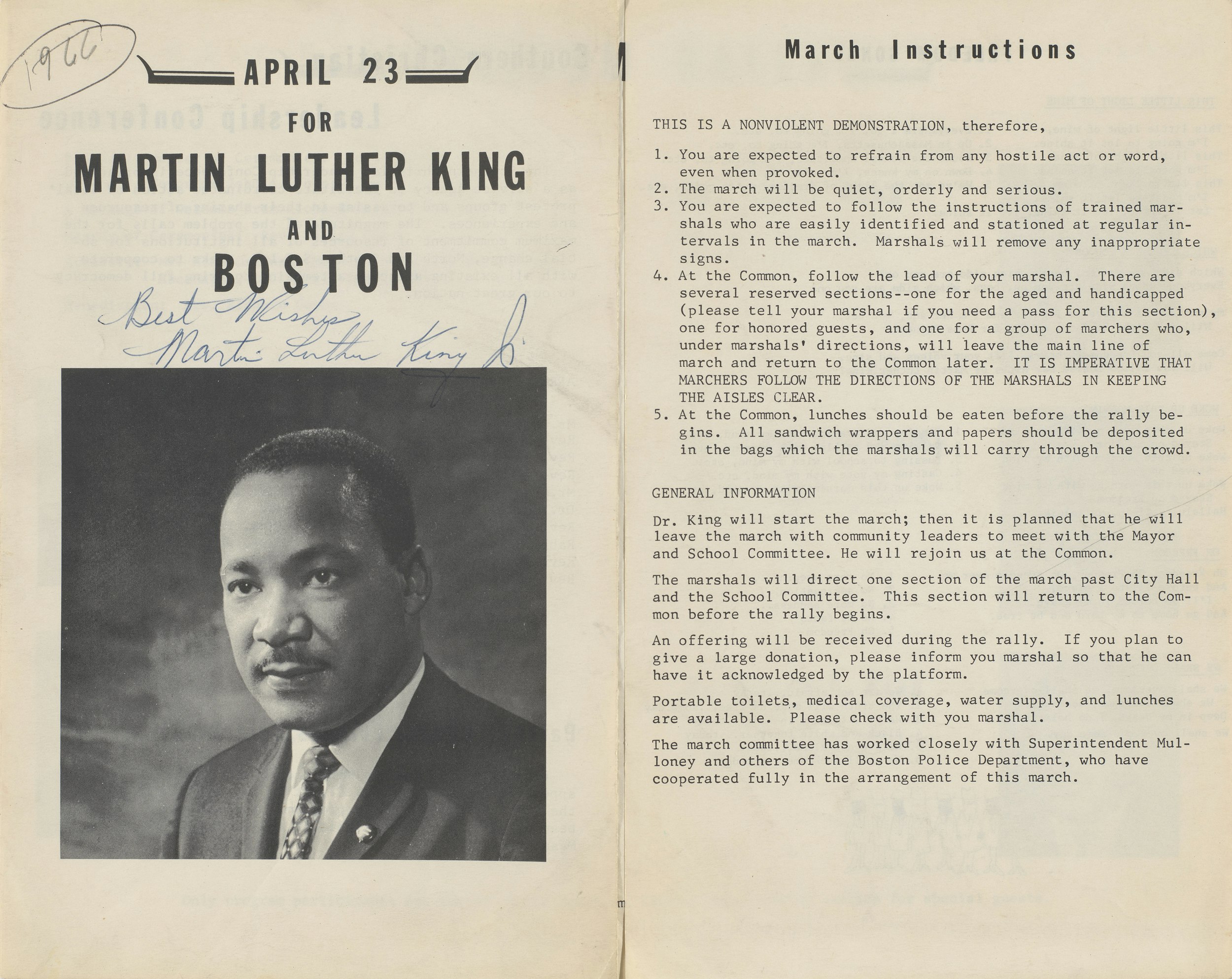

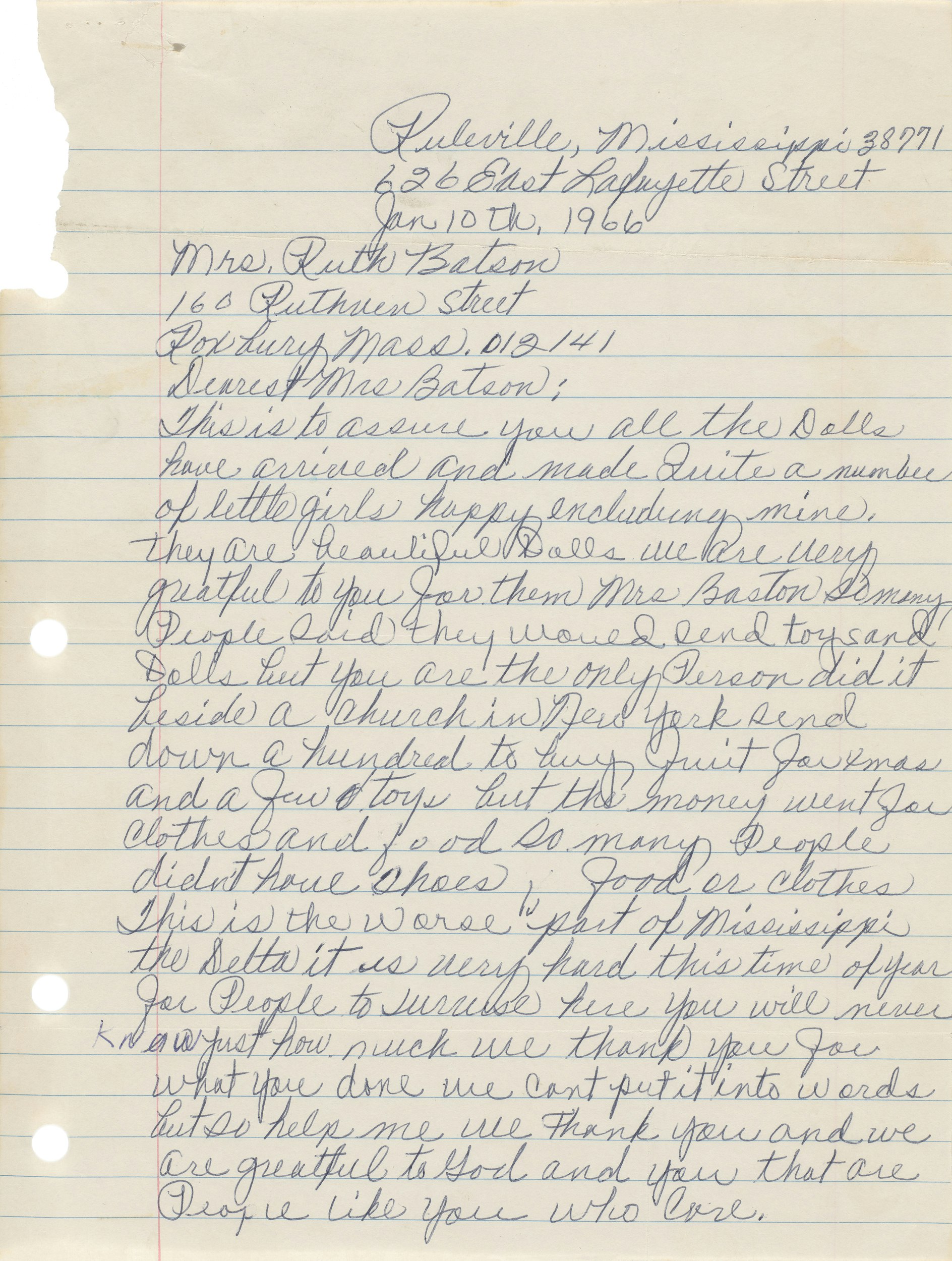

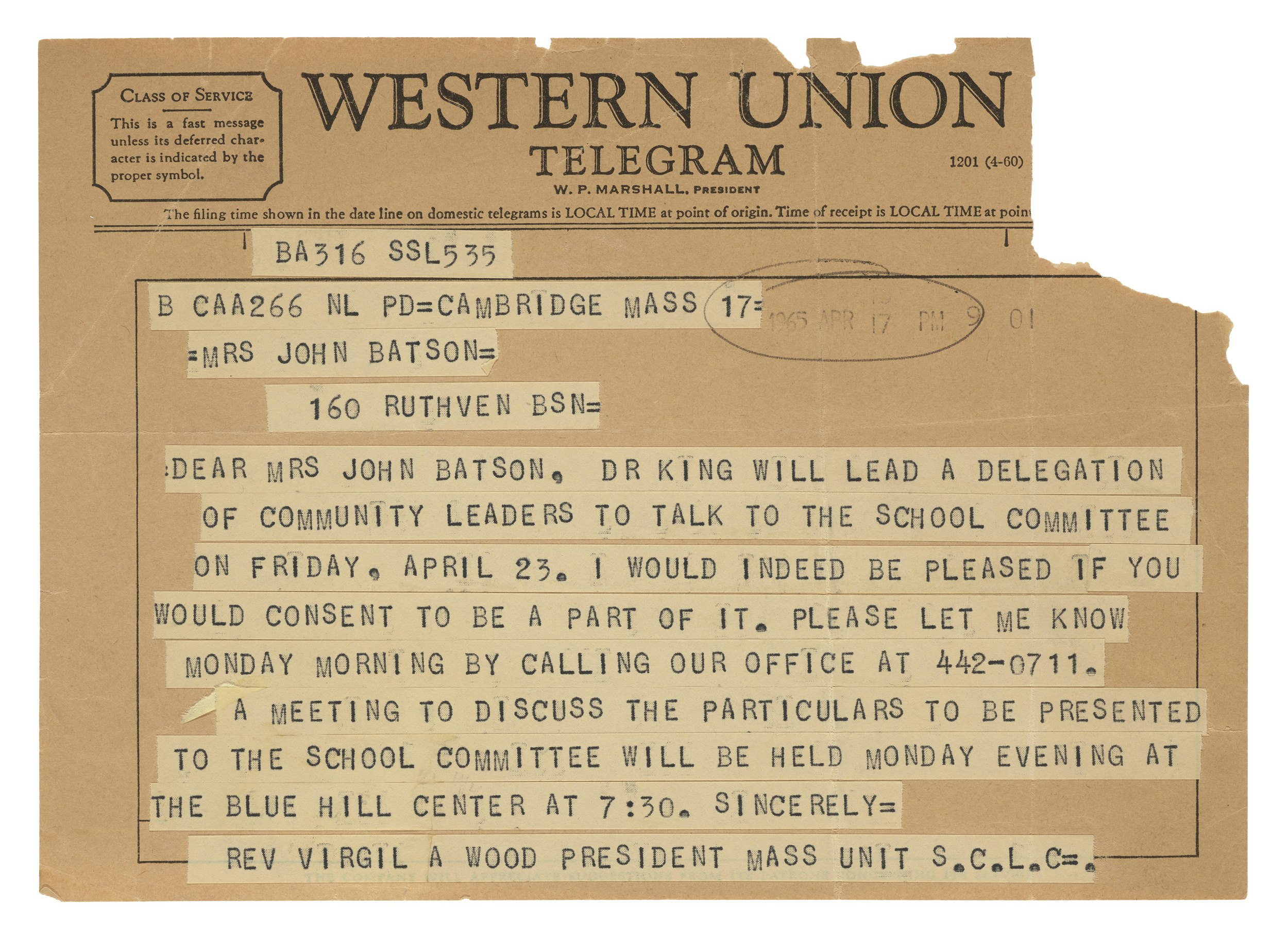

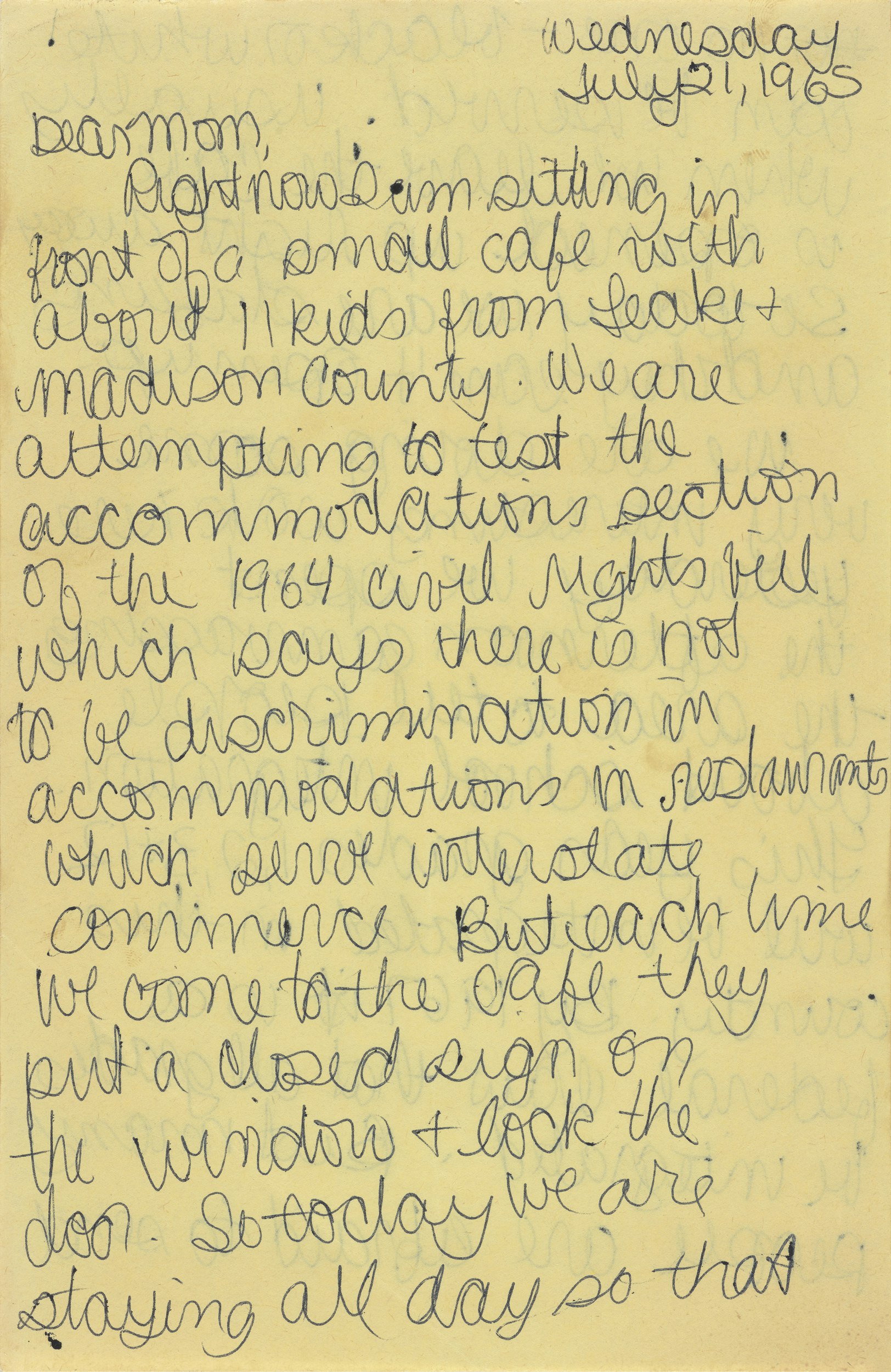

Recognition of shared struggles required reckoning with distinct identities. The daughter of sharecroppers, Fannie Lou Hamer rose to become a leading organizer for the civil rights movement of the 1960s, co-founding the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to protest the denial of voting rights for African Americans. Born in Roxbury to a middle-class African American family, Ruth Batson was a nurse, an organizer for public school integration, and chairwoman of the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination. Separated by geography and class, Batson and Hamer were brought together by the National Council of Negro Women’s Wednesdays in Mississippi program, which sponsored trips by Northern women of diverse faiths and races to connect with civil rights activists in Mississippi. These encounters fostered relationships between Northern and Southern peers who provided one another with solace throughout the resistance.

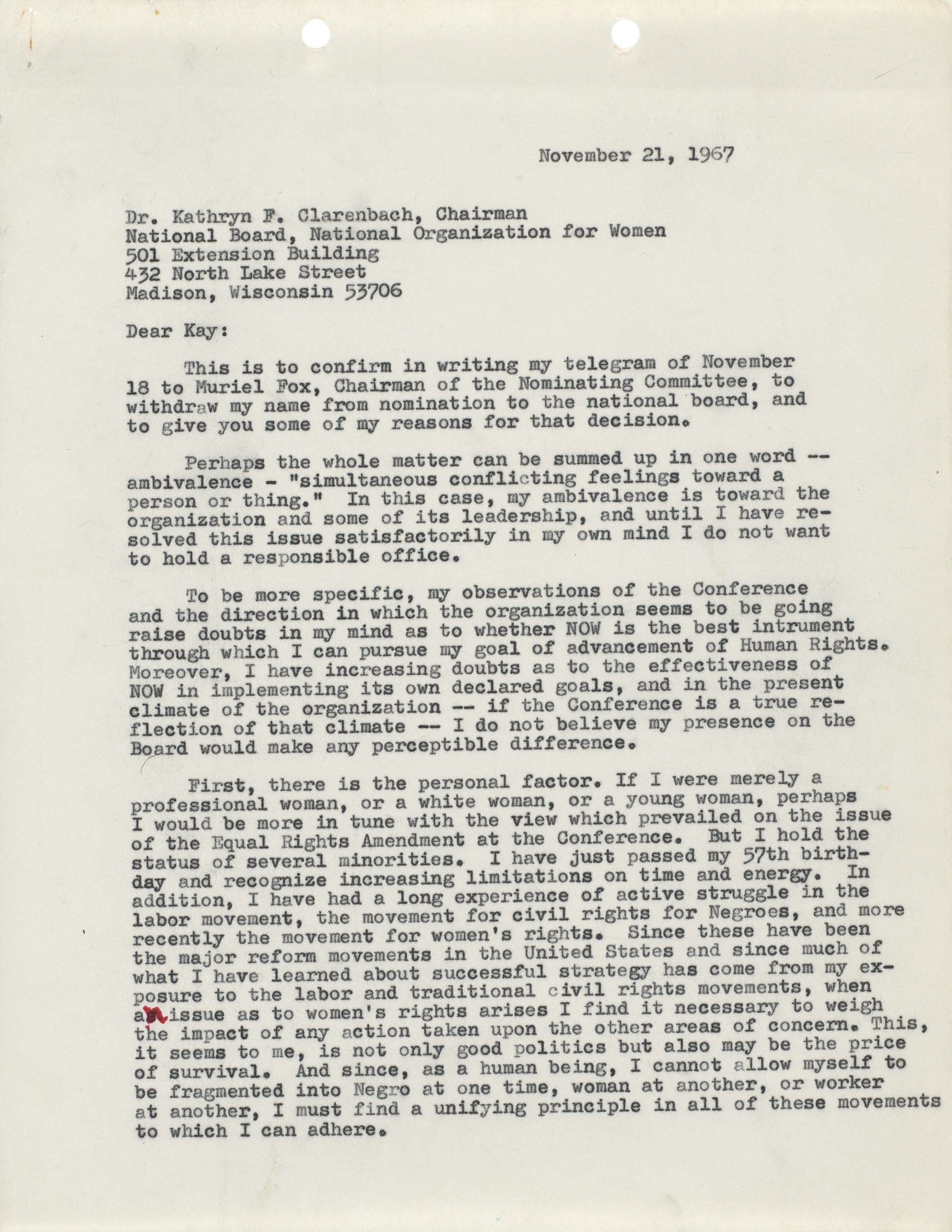

The lawyer and civil rights activist Pauli Murray participated in the founding of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, a continuation of her work with the National Women’s Party to add sex as a protected category in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Murray distributed petitions, wrote letters of support, cultivated sister organizations, and consulted on NOW’s strategic direction. In a November 1967 letter, Murray voices her doubts about NOW and whether it could represent all women. Realizing that her white counterparts were unable to identify with her experiences as an African American woman, Murray expressed her conviction that an intersectional approach to women’s liberation was necessary.

United in Our Mission

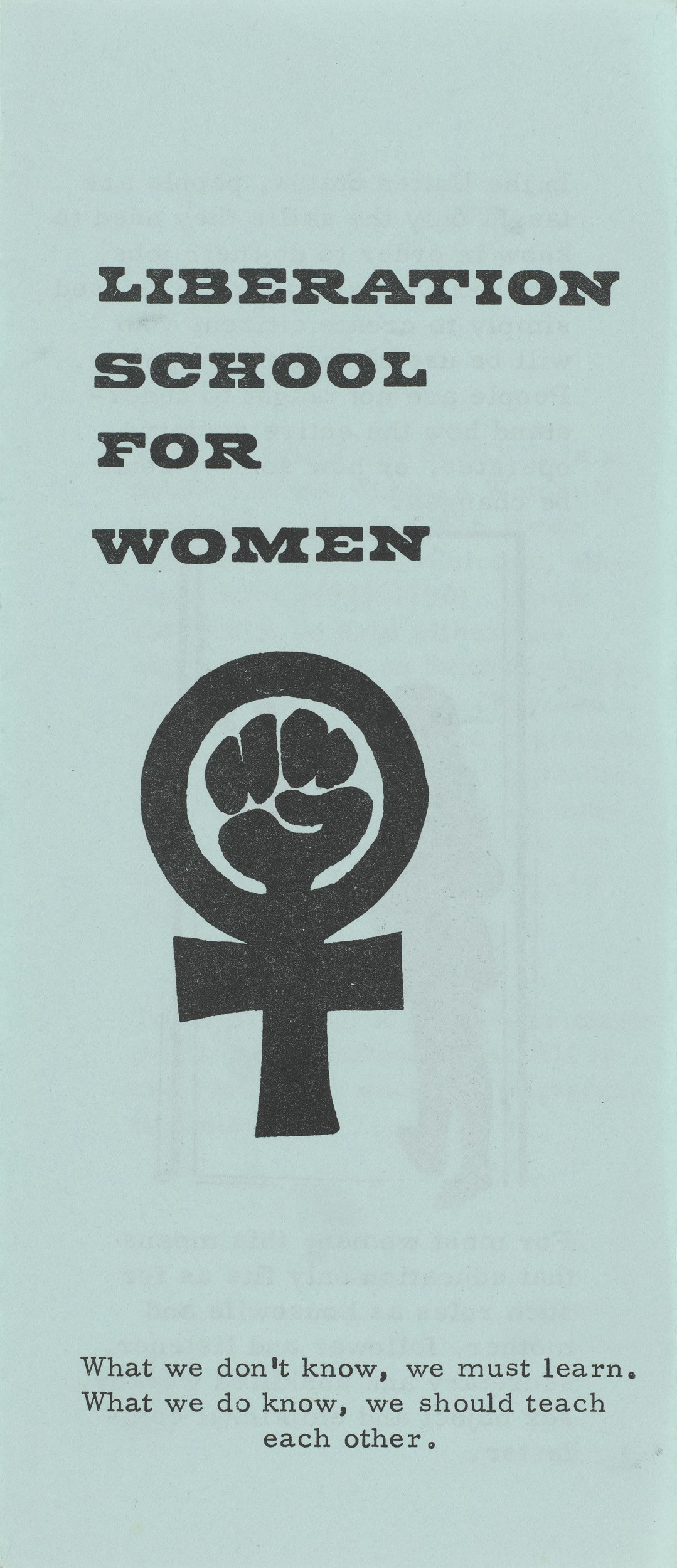

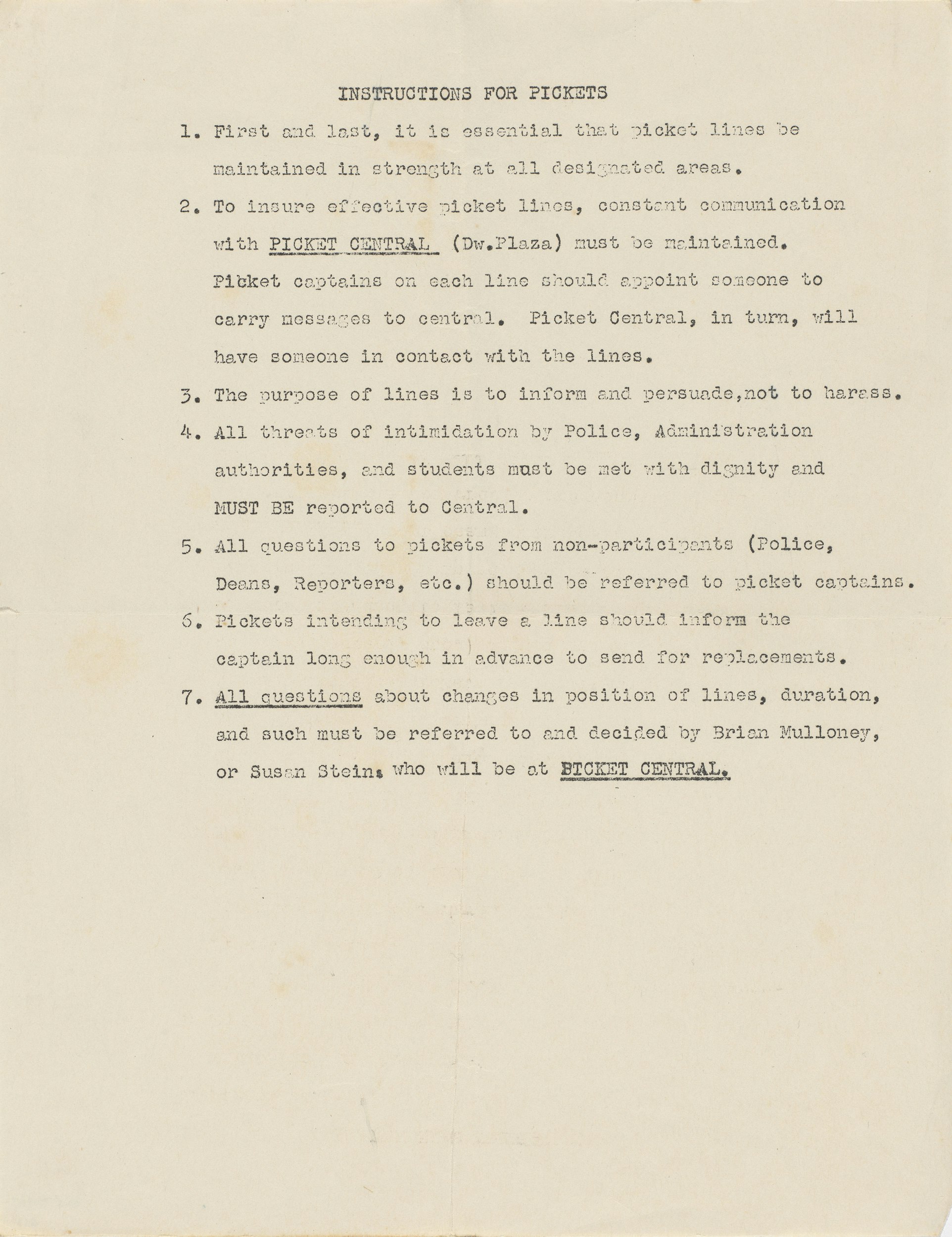

The labor rights activist and community organizer Vivian Rothstein dedicated herself to concurrent liberation movements starting in the 1960s, while she was a student at the University of California, Berkeley. Rothstein joined the Congress of Racial Equality and later traveled to Mississippi as part of a student coalition allying with white Mississippians to support the integration of African Americans in schools and businesses. Picketing and demonstrations were part of concerted actions to drive African American voter registration and effect change. Rothstein later moved to Chicago to develop solidarity networks of lower-income white workers with African American organizations. A co-founder of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, she worked alongside other activists to strategize and lay the foundation for consciousness-raising. The union’s Liberation School sought to provide introductory courses that would help women develop a common framework for understanding oppression while acquiring practical skills in nutrition and car repair. United and excited, these groups were galvanized by leaders like Rothstein who encouraged others to make history and fight for social justice in society.

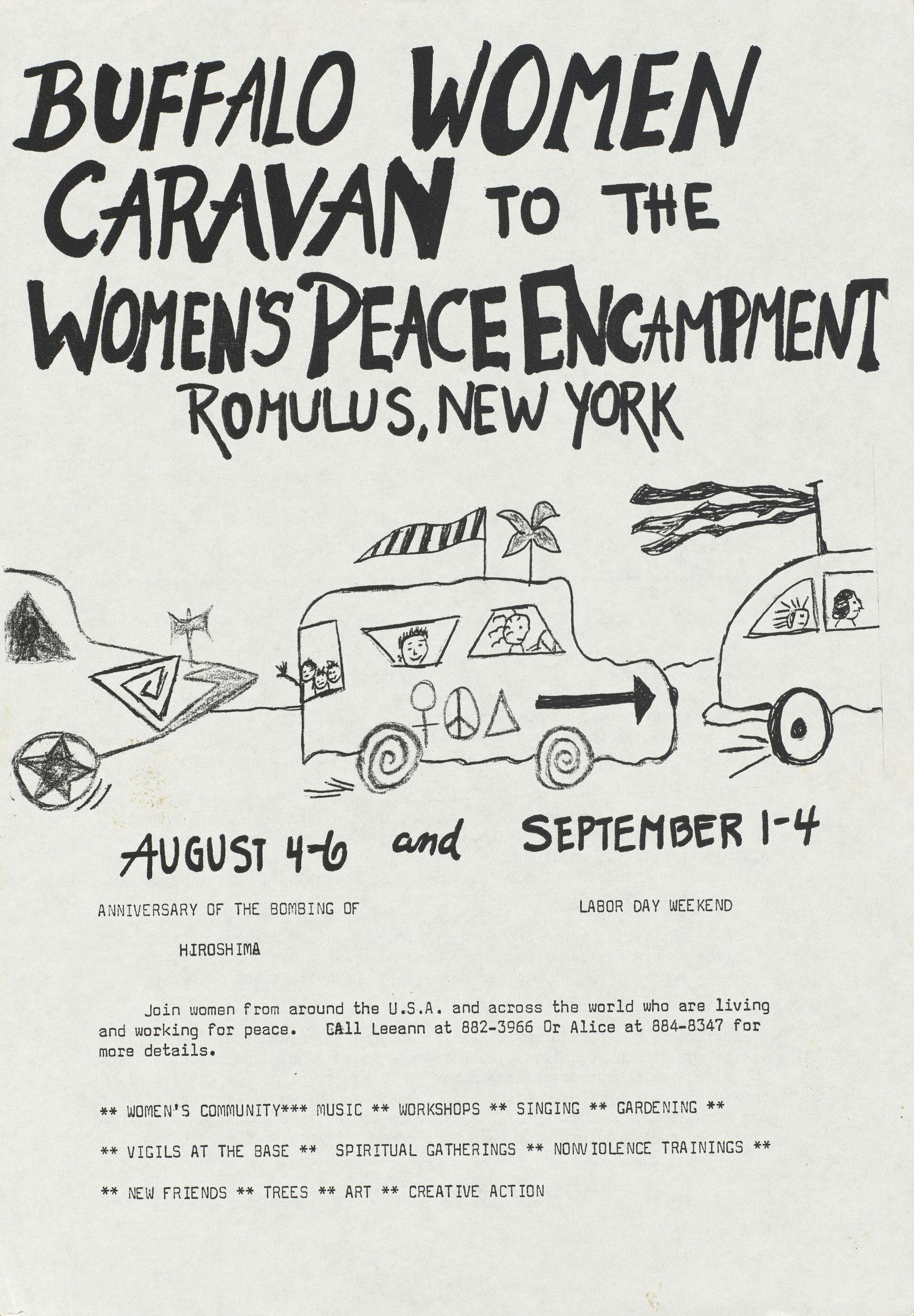

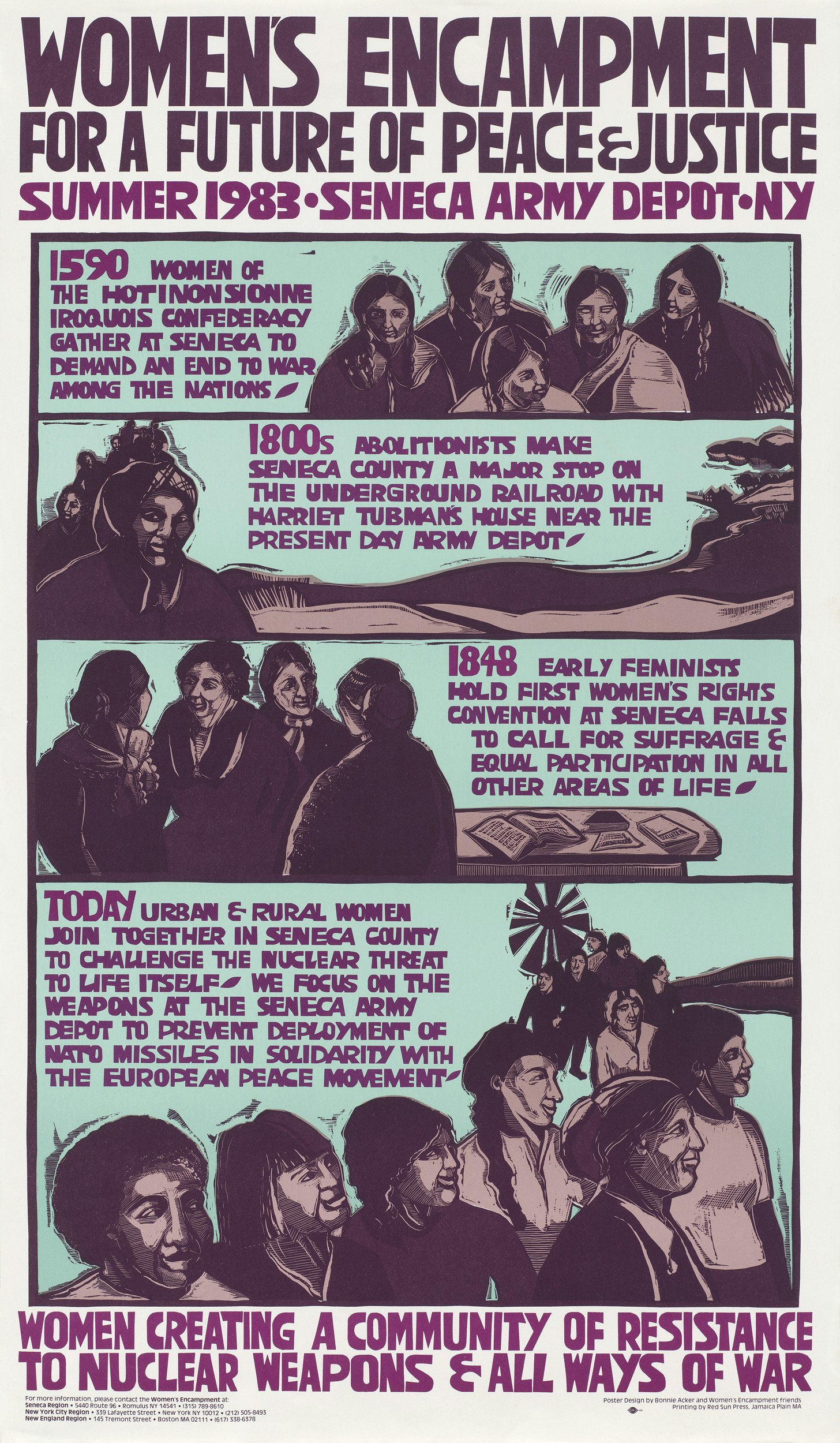

Untangling Webs and Making Peace at the Camp

Joyous surprises, moments of human connection, and a fiercely articulated No to U.S. military spending: these are just a few outcomes of the Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice (WEFPJ), a collective happening that gathered antiwar activists outside Seneca Falls, New York, to protest the development of nuclear weapons throughout the early 1980s. Actions included marches, vigils, street theater, and teach-ins with the intention of interrupting the Seneca Army Depot’s daily activities. An experiment in communal living, the encampment used “feminist processes” to create noncompetitive and consensus-driven policies and reform. Although the emphasis was on the connectedness and multimodal spirit of their activism, the predominantly white and middle-class members of the encampment had disagreements over their approach and the scope of their work. Their goals grew to support environmentalism, civil rights for all genders, and the ongoing struggle against patriarchy.

Remixing Verse: Using the Past to Inform the Present

A fervent desire for a new world order, coupled with a strong do-it-yourself ethos, punctuates the dispersed antiwar movements of the 1980s. The Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice (WEFPJ) opened in Romulus, New York, on July 4, 1983, as ground zero for activists to gather, plan, and protest the deployment of nuclear weapons to Europe. Influenced by similar antiwar movements in England, the WEFPJ chose this site specifically because it bordered the Seneca Army Depot, which housed a large stock of nuclear weapons, and was also the site of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, the event that launched the U.S. women’s suffrage movement. Demonstrators used posters, banners, objects such as a pillowcase, and even their own bodies strategically placed against the base’s fences and barriers to draw attention to the dangers of a society centered on American militarism and patriarchy.