Accompanied: The Artworks of Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman

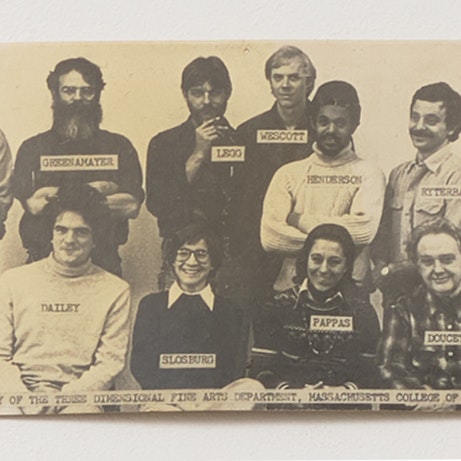

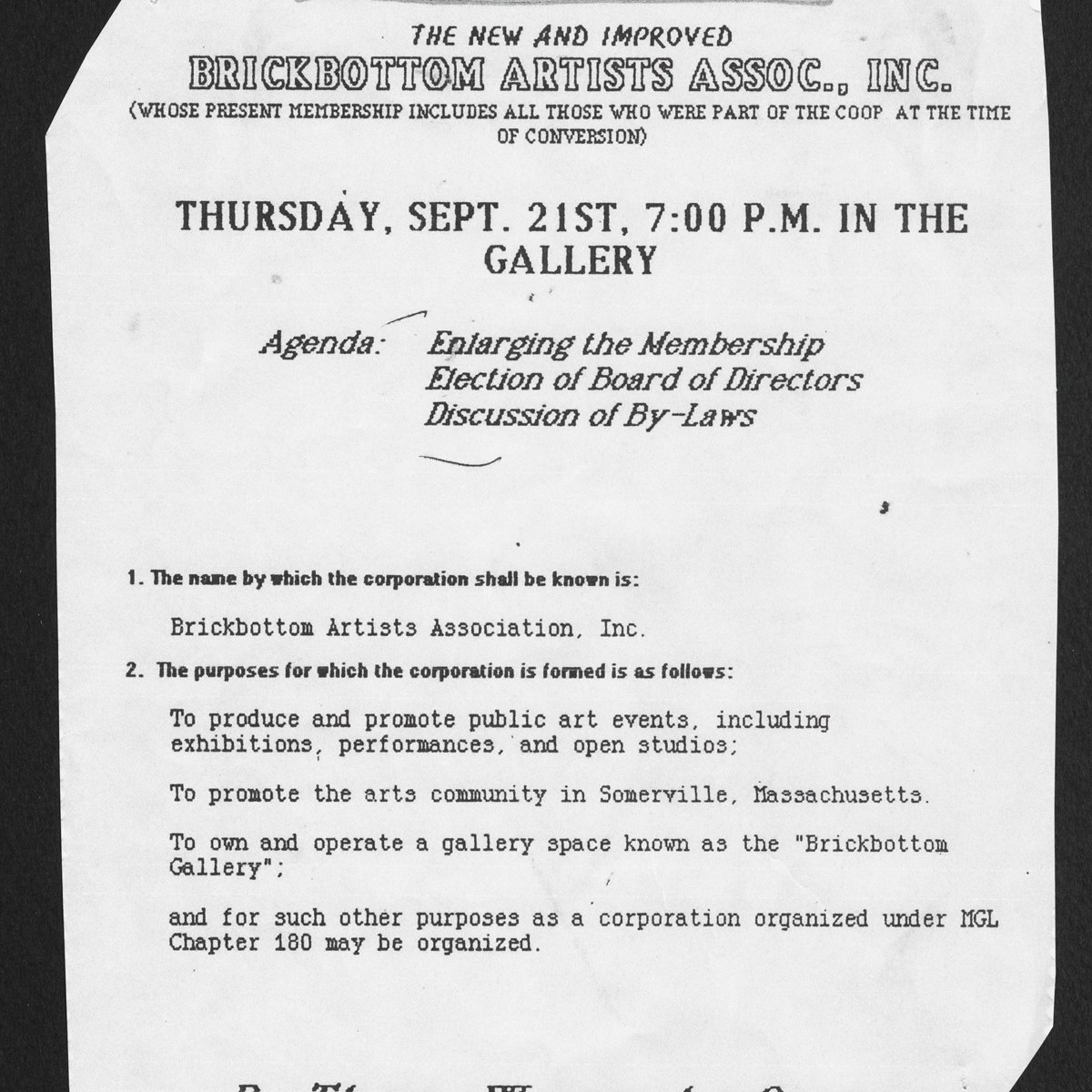

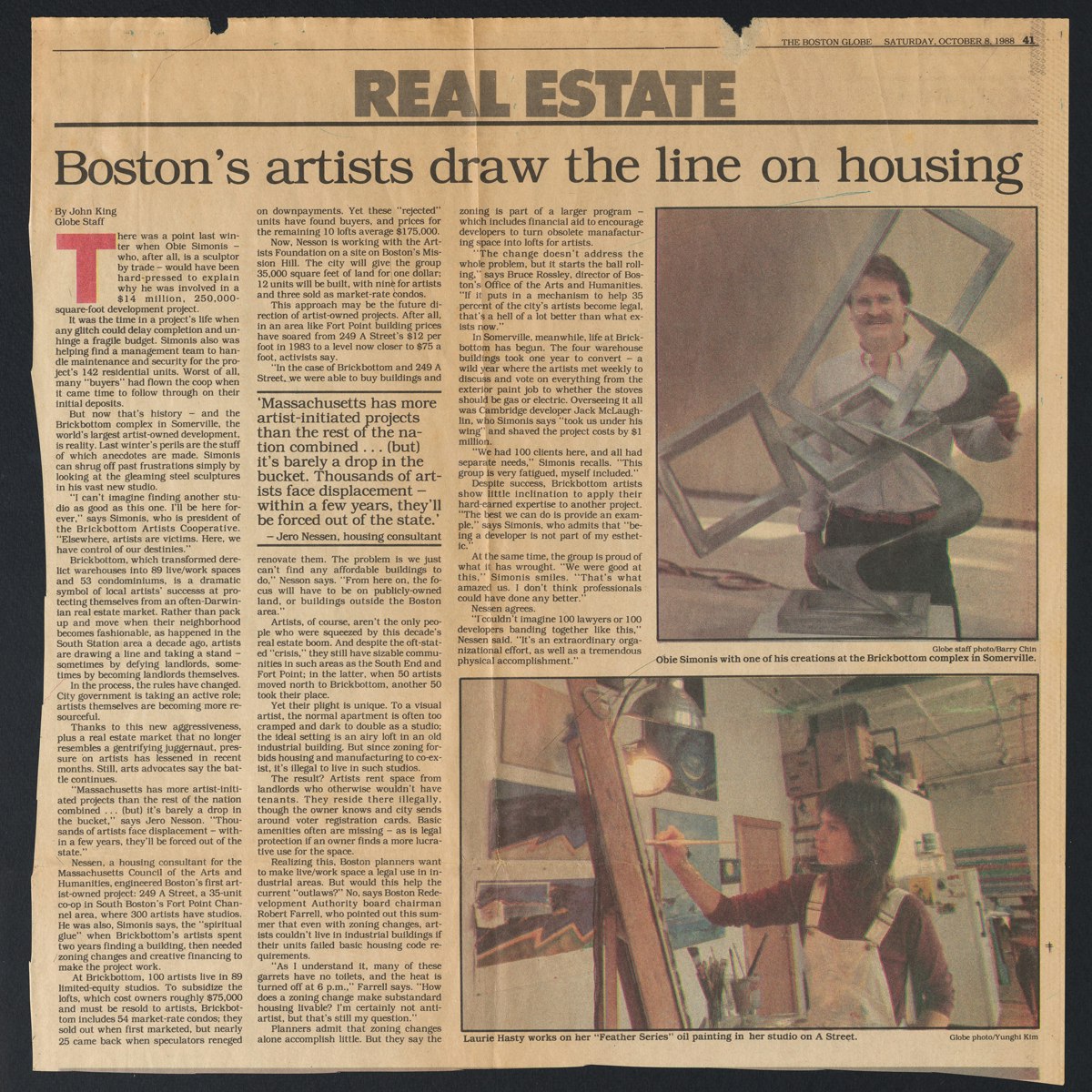

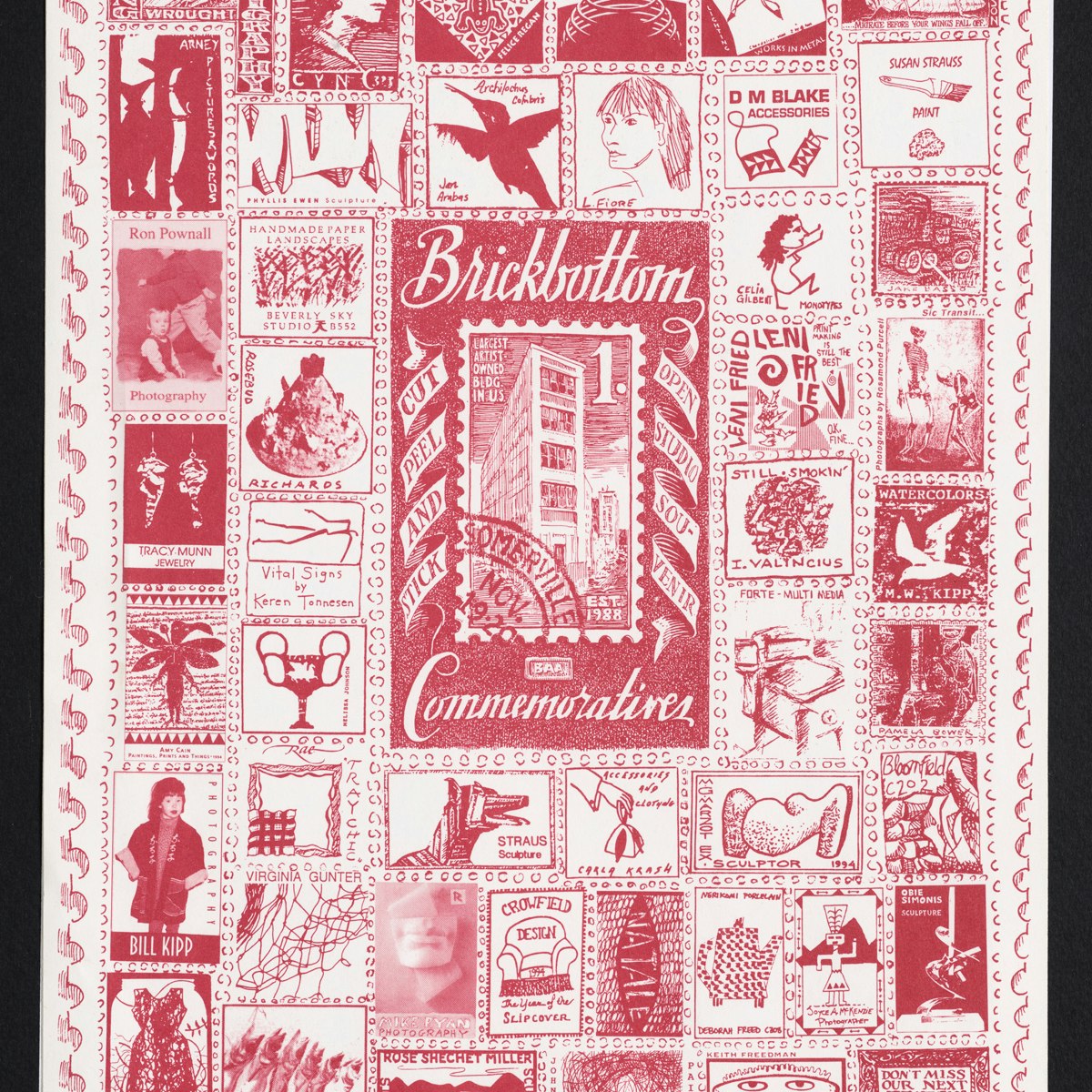

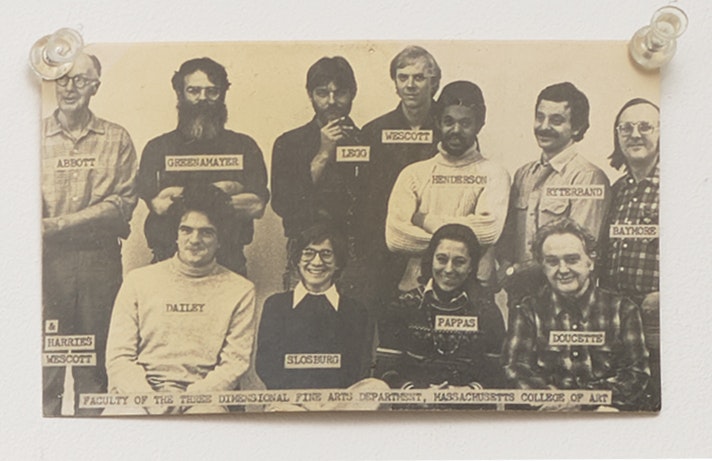

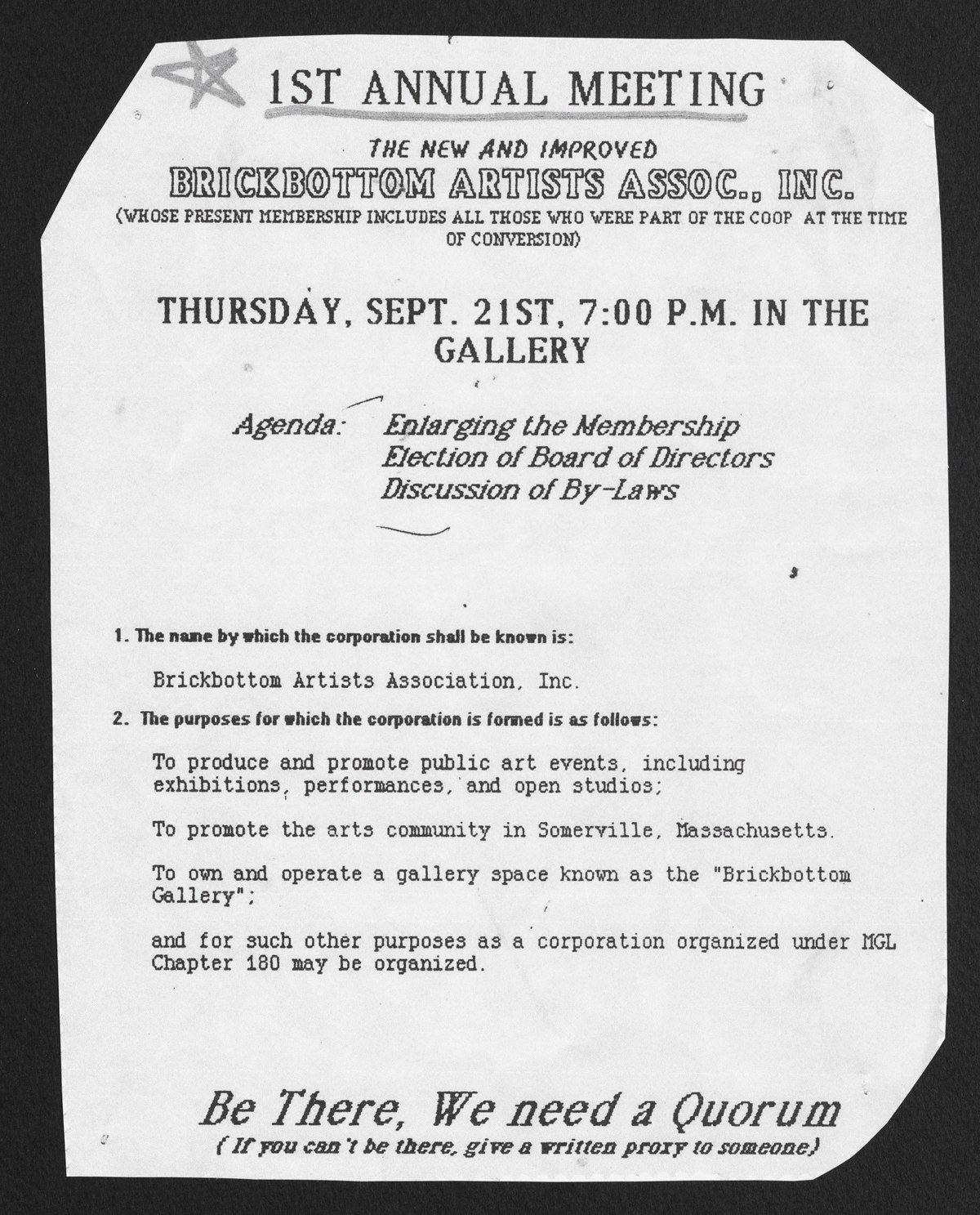

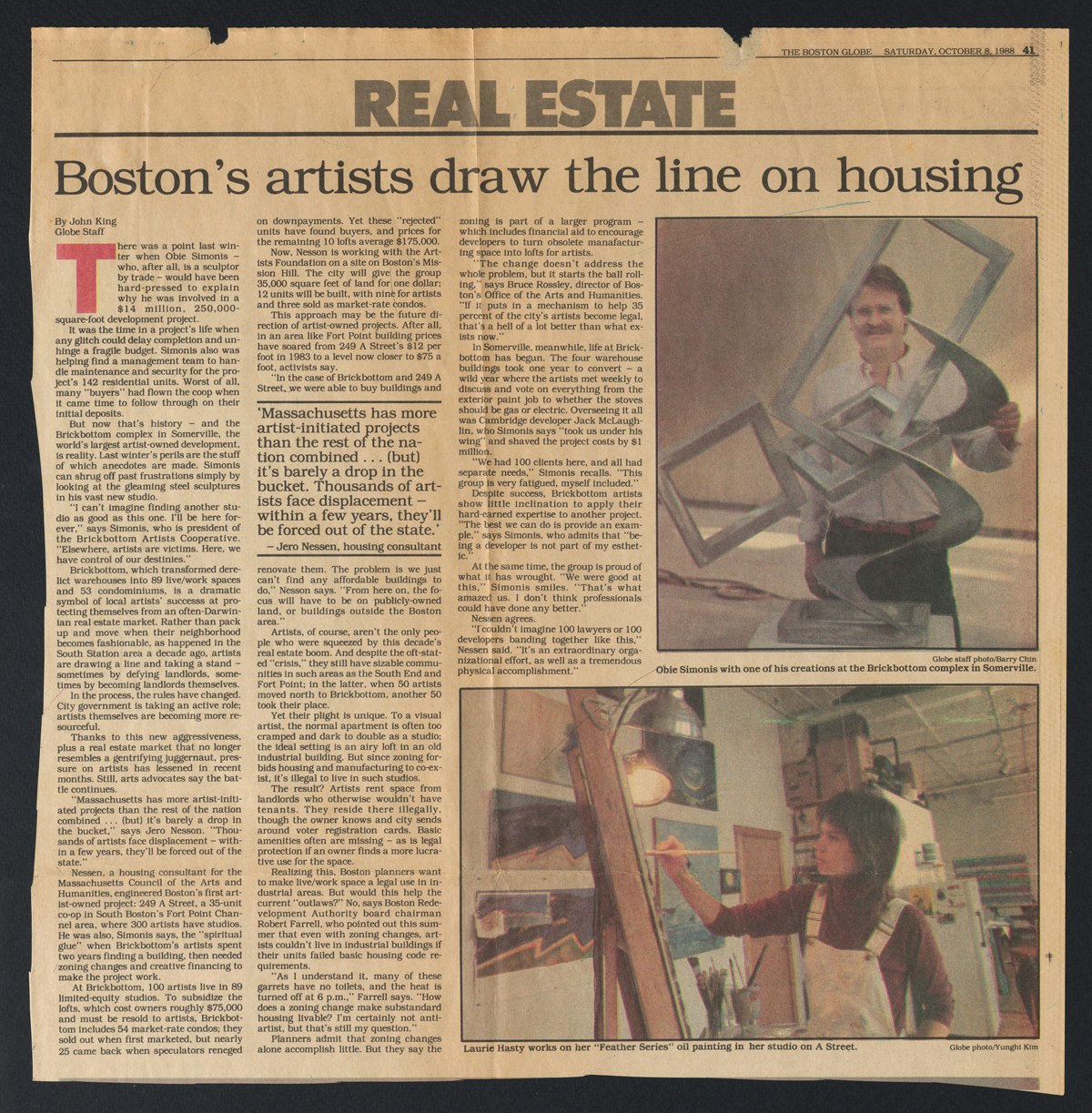

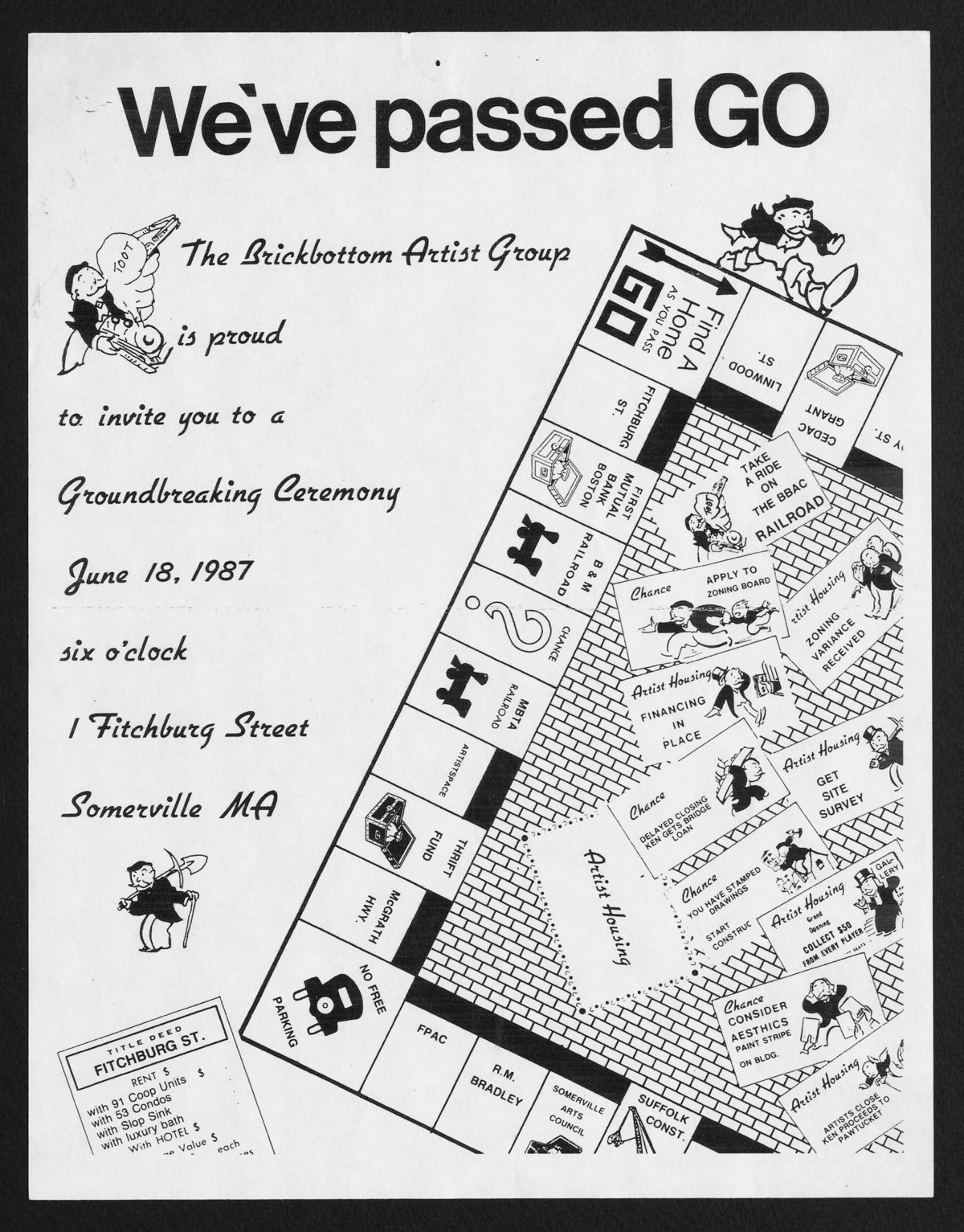

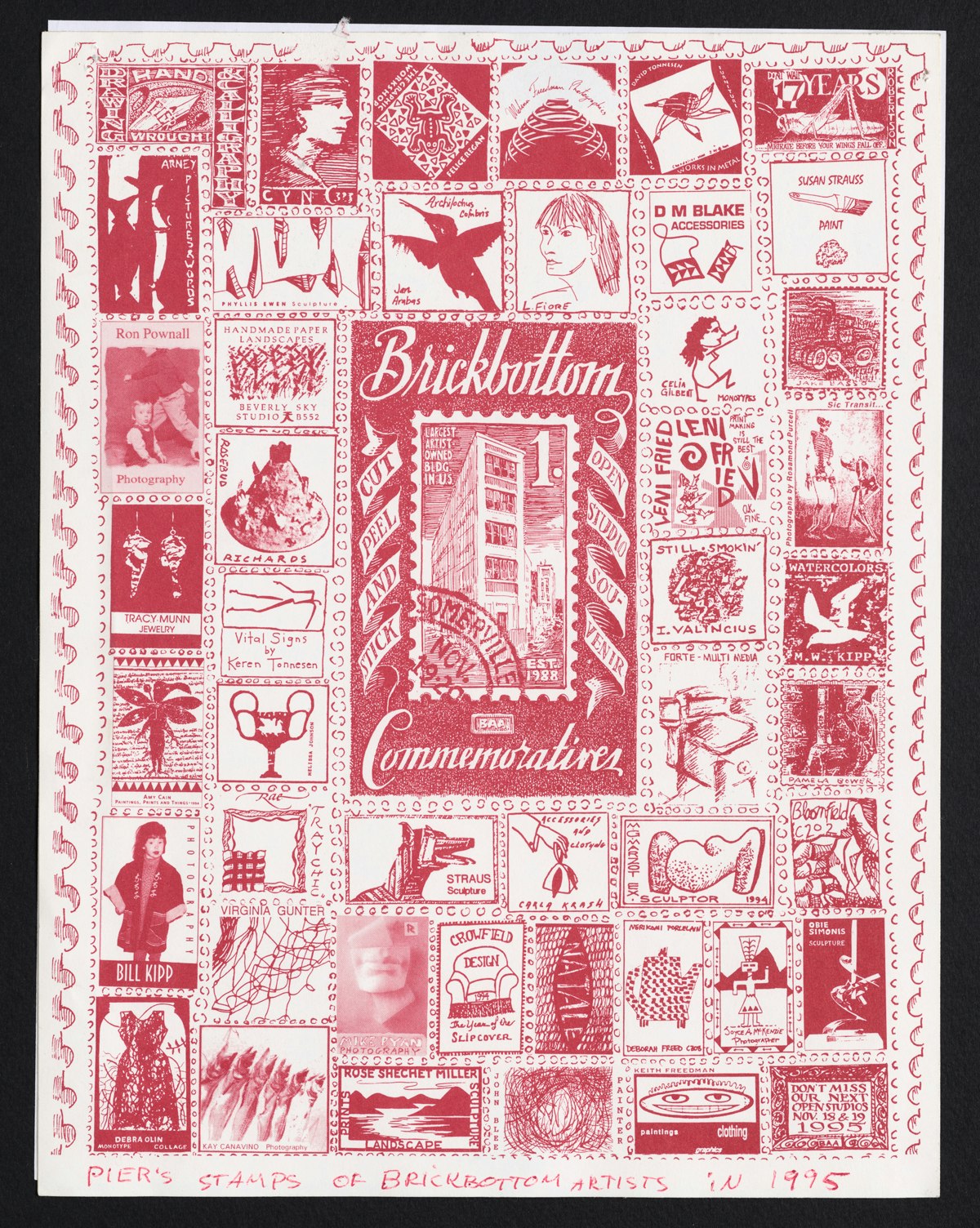

The virtual exhibition Accompanied: The Artworks of Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman presents a pair of artists whose work was transformed by an abiding friendship. Pappas and Slosburg-Ackerman, both fellows at Radcliffe’s Bunting Institute in the 1980s, have sustained a conversation over four decades about artistic endeavor, studio practice, and pedagogy. The artists were members of the founding group of the Brickbottom Artists Building—one of the country’s first artist-developed live-work buildings—and are professors emeriti at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. They have continued to work in adjoining studios for more than 30 years and have taught generations of artists.

This virtual exhibition, captured from Pappas and Slosburg-Ackerman’s studios, reflects on how their artistic practices were shaped by a decades-long friendship working in close proximity. What are the aesthetic and political possibilities of friendship, particularly in relation to women’s art? In friendship, we see a model of collectivity that is based not in the family or state, but in natural affinities—a mode of mutual reciprocity and exchange that resists easy codification and offers the potential of liberatory politics.

Based in the site of their artistic work and departing from the mythos of the individual (male) artist working in isolation, the exhibition considers the ways in which women's art is shaped by the conditions of its making. Their lives, and work, are deeply embedded in complex infrastructures of support; interdependent systems of responsibility and care. During the online exhibition run, audiences will also learn, through an array of public programs, about how women’s relationships endure during our current time of isolation and upheaval.

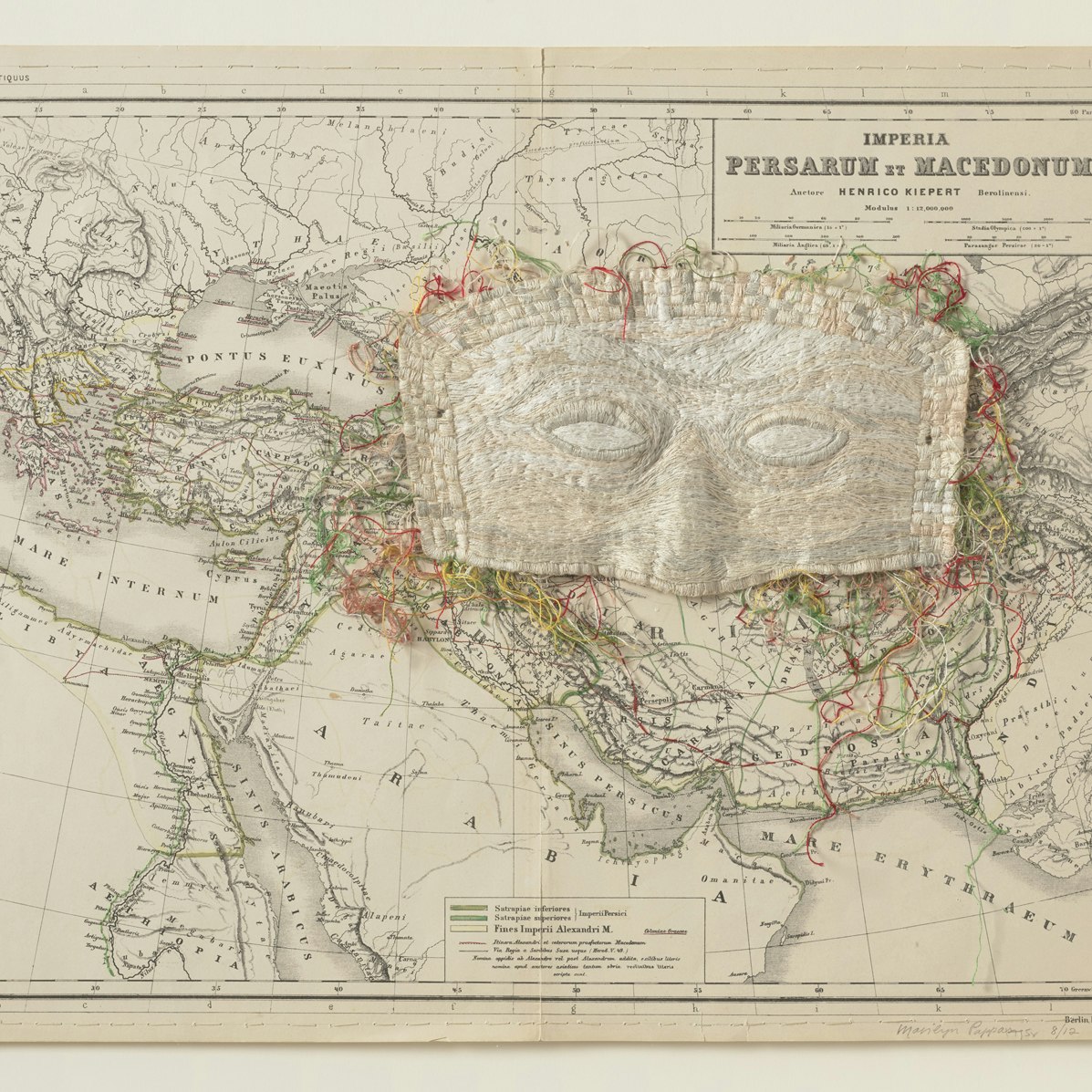

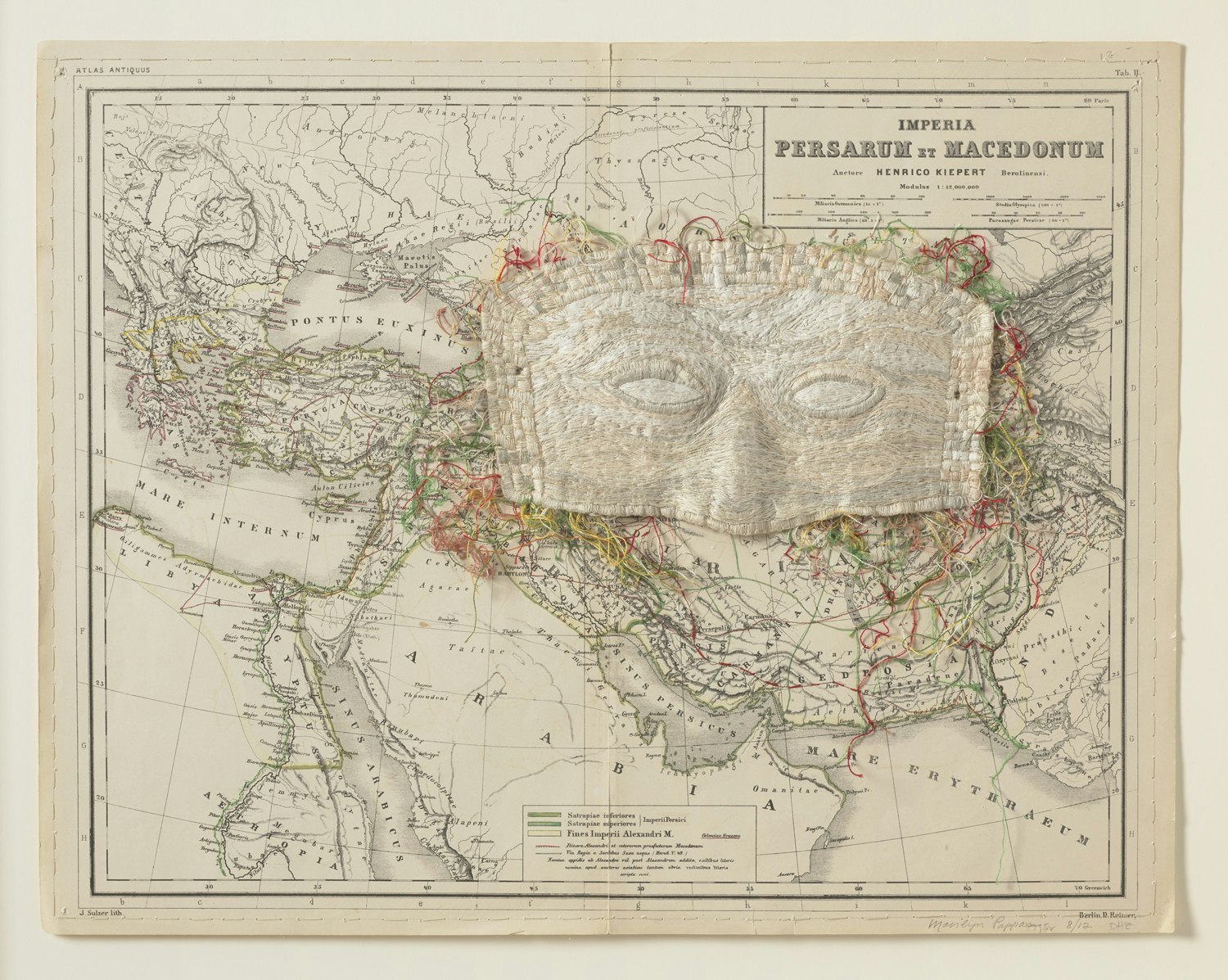

Pappas’s Mediterranean journeys deeply influence her subject matter. She is inspired by ancient Greco-Roman vases and sculptures of women, often broken. Unlike Pappas’s stone source material, her soft substrates have evolved from early work with found garments to paper, cotton, and linen. Her color palette has changed too: initially, she embroidered in the cool tones of marble—whites and greys, with the occasional pop of gold thread. When she learned that the ancient sculptures had been painted with vibrant colors when they were created, she enthusiastically picked up brightly pigmented floss and enlivened the surfaces of her own work. As Pappas’s work has developed, so have the possibilities that her female figures embody.

Marilyn Pappas at work in her studio

Marilyn Pappas sits for hours with the life-sized torso of a woman sketched in needlework on her lap, her needle moving between her fingers. Cotton threads of all colors are jumbled next to drawings and books on the studio coffee table. Her most recent works, a series of women’s bodies with missing heads and arms, present two views of a figure: the front shows a sensual image of a woman and the back is an intentional wilderness of loose threads. The sculptures are slipped, like a piece of clothing, over a wooden base that gives them an upright posture. The series is titled Nevertheless She Persisted and is a reminder of the political and gendered meaning the word “persistence” has taken on in recent years, shorthand for women’s insistence on being heard and seen, even in the face of interrogation, interruption, and sexism. The headless figures of Pappas’s embroidered artwork nevertheless stand erect: female, powerful, beautiful, and free.

Listen to Marilyn discuss her work

THIS IS A TRANSCRIPTION OF AN INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY SHRUTHI VENKATA WITH ARTIST MARILYN PAPPAS IN JULY 2020.

MARILYN PAPPAS: My name is Marilyn Pappas. Well, I’ve been working for a very long time. So, for the first five years, I tried this, and I tried that. My early work with fabric was actually was fabric collage. I was making these -- first making landscapes with different kinds of fabric and mounting -- sewing them onto other fabric. And then I started putting either fragments of clothing or whole objects into this cloth -- really assemblage. So those -- while they weren’t totally figurative, they implied the figure. And from, I would say, the mid-’60s to the late ’70s, I was working in this manner.

And I became really interested in Mediterranean countries, architecture, art. And little by little, it sort of winnowed its way down to classical statutes especially of women. And so, then I tried to figure out what could I do with cloth and yarn or thread that -- with the subject matter? And I spent actually two or three years trying all different ways of doing this. Finally ending up with the stitched figures that I’ve been working on now -- I never thought I would work on them that long. But the series has lasted over 20 years now. And now I’m working on a series of three-dimensional pieces so. So, you never know what’s going to come next when you’re an artist which is really interesting. I used to tell my students that because when we had our history when I was an undergraduate I think my least favorite time was ancient Greece. And look what happened. So, you don’t know. You just don’t know.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: My name is Shruthi Venkata. What is your process to create an artwork, in general, and specifically for Nevertheless She Persisted?

MARILYN PAPPAS: With that, which is my current focus, I -- the first thing I do is I look through my countless pictures of Greek and Roman statues of women. Until I settled maybe on a little pile and then I made a few sketches. I would take a big piece, a roll of poster paper, and I would just make really fast sketches of what I’m thinking about. And when I have it the size I want it, I cut it out. And I put a piece of linen up. I put that on the linen. And I trace around it, so that I will have a size. And then I sort of redraw the outline and a few guidelines. And then I usually stitch the outline, so that I have that in my mind. And then I usually start -- I figure out the colors I want to use. And I call them Nevertheless She Persisted because I loved that phrase. That I guess was applied to Elizabeth Warren.

And because I felt that these statues that I were getting -- was getting inspiration from -- and they end up really not looking much like (laughs) the statues at all. But they’re my primary inspiration. And I felt that even in their broken, battered state -- they wouldn’t have a head. Or one breast would be off or whatever. That they still -- these sculptures that we look at were broken, but they were beautiful. And we learned to love them that way. And for me, they were metaphors of women that as you age as I have, as things happen to you, you may be broken in different ways. Broken and hurt and changed. But you could still be strong. You might be -- still be vulnerable, but you could still be strong.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: Thanks for sharing that story. Tell us about your time at the Bunting Institute, your day to day, standout experiences, anything.

MARILYN PAPPAS: Well, my time at the Bunting was wonderful. I felt as though I had a benevolent patron. But, it was also partly difficult. Not because of anything the Bunting did or not did, but it was a problem in my personal life. The man I had been living with throughout the seventies, potter and sculptor, William Wyman, contracted brain tumor at the age of 57. So the first several months there were incredible. I was working on collages at that point. And I did a lot of work during those first several months. It was wonderful. And I was excited about the work. The other fellows were wonderful. One of the things that I loved about it was I had this great studio, which was over the Schlesinger Library. And I also loved that every week there would be a meeting with some kind of a lecture or performance or whatever by a fellow. And I felt as though I was getting a liberal arts education. I mean it was all women. And it was much smaller at that time.

So that was all wonderful, but the second year Bill was in and out of the hospital. It was really hard. And he became very ill. But I couldn’t get to the studio very often at all especially in the last few months. He passed away in April, 1980. And then about a month later, I went back to the studio, and I started working like crazy. (laughs) And I remember the first day I was back there I was working on a collage, which I had sort of left hanging. And I felt all of a sudden this sort of feeling of joy. I mean it was really strong. I’ve told this to other (laughs) people. I mean it was just crazy. It was like that first feeling of joy that I had since Bill got sick. And I realized how important my work was to me and how fortunate I was that that -- even though one very important part of my life had been taken away, this was still with me. Nobody could take it away. I was still going to have it. So it was an amazing time and a difficult time. But I just was so grateful for it.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: Thank you for sharing that story with us.

MARILYN PAPPAS: I know. Well, it’s an important story, and it affected my fellowship and my work and myself.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: Last question is -- tell us about your friendship with Jill and how it has played into your practice.

MARILYN PAPPAS: Well, I met Jill when I came to Mass Art. And so we would have meetings, and we just slowly got to know each other and like each other.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: Would you say that your relationship has affected your art in any way or not at all?

MARILYN PAPPAS: Oh yes. I think it does affect my art because we talk to each other about our work. We critique each other’s art. Yes. She has helped, I think, a lot in that I always have someone I can talk to about what I’m doing. And if I have problems with my work, we can talk about it.

MEG ROTZEL: I’m Meg Rotzel. This interview was conducted in July 2020 with artist Marilyn Pappas and Harvard College student, Shruthi Venkata. It was edited by Joe Zane for the online exhibition accompanying the art works of Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

END OF AUDIO FILE

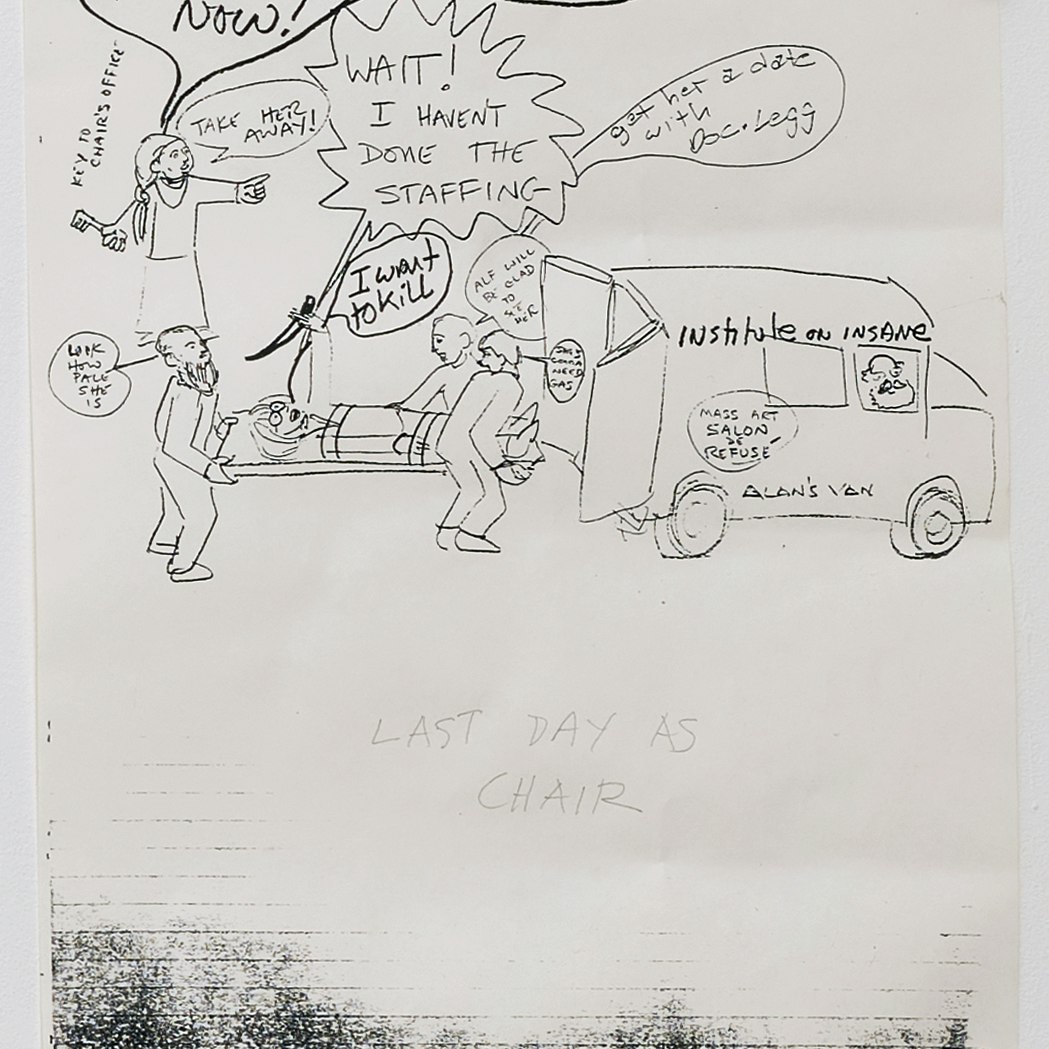

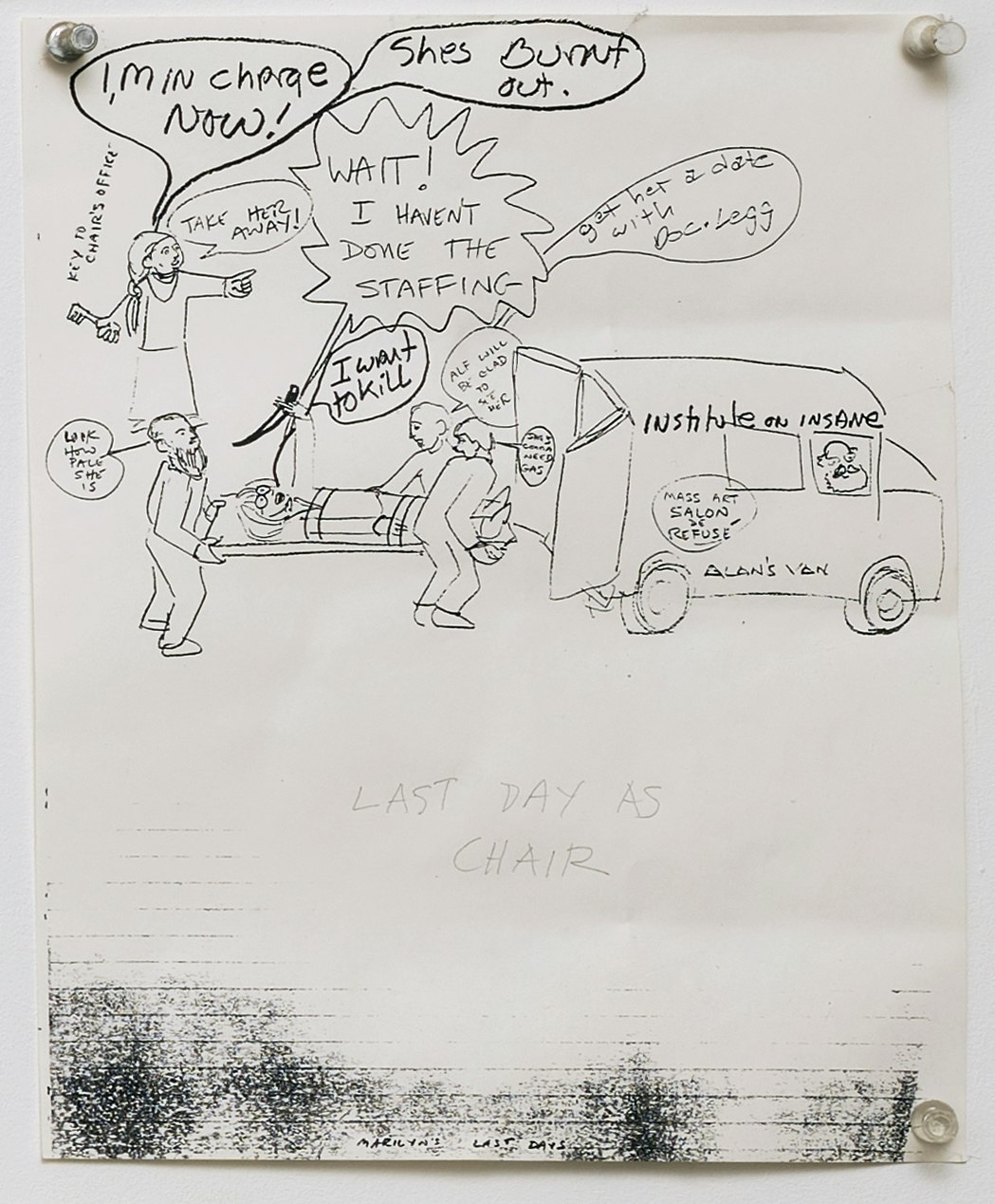

Marilyn Pappas (b.1931) is an artist based in Somerville, Massachusetts. Pappas creates large-scale textile works developed from sculptures of ancient goddesses. The three-dimensional figures stand at the intersection of sculpture and garment and imagine ancient artworks as they evolve and survive over centuries. Although broken, faded, and disintegrating, the works are metaphors for the strength and power of women in the #metoo era. Pappas’s work has been exhibited in many galleries and museums during the course of her over-60-year career, including the Currier Museum of Art, the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, the de Young Museum, Fuller Craft Museum, the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art, Pennsylvania State University, Krannert Art Museum, the Museum of Arts and Design, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Staten Island Museum. Pappas is a professor emerita at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, where she taught from 1974 to 1994 and was chair of the 3D Fine Arts program for 9 years.

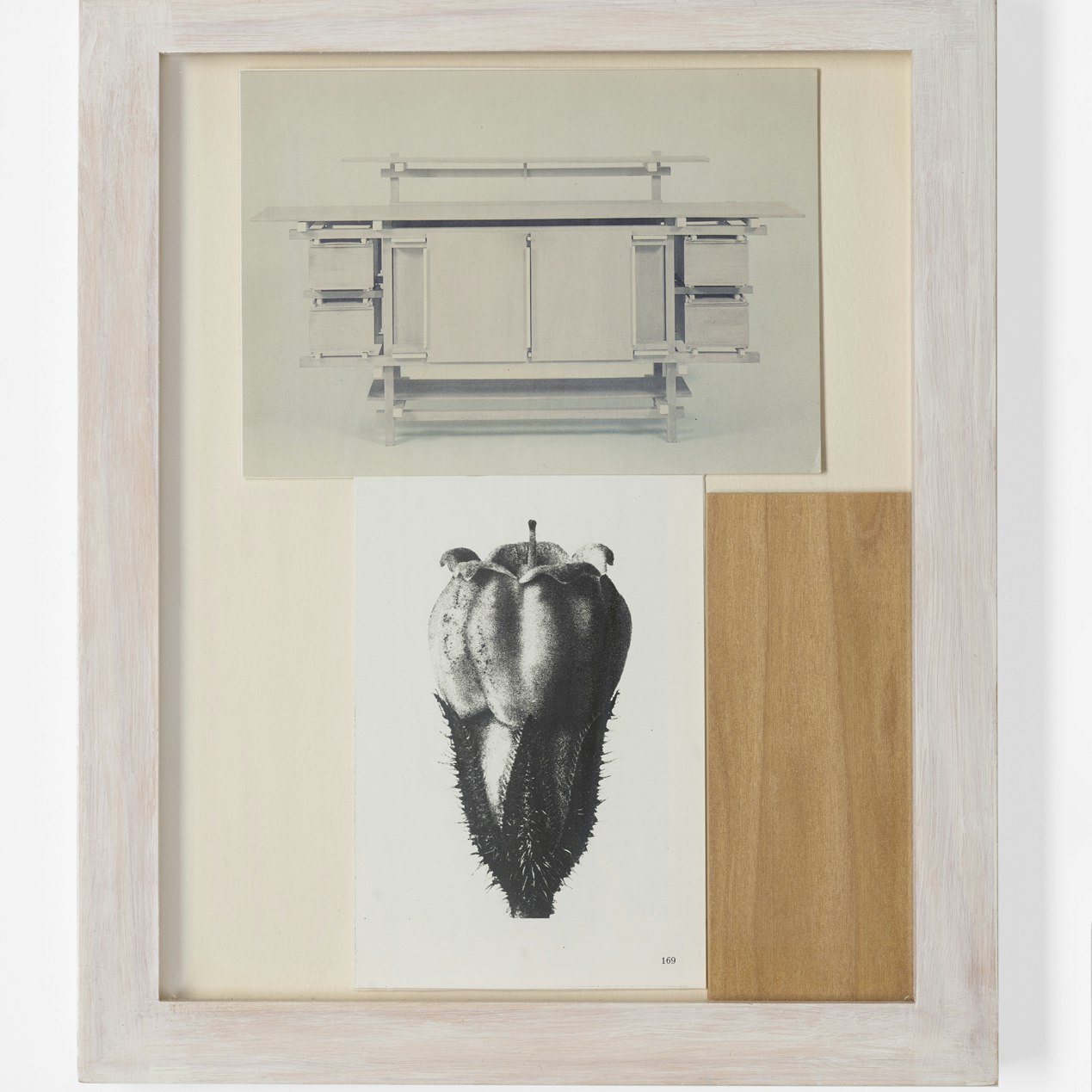

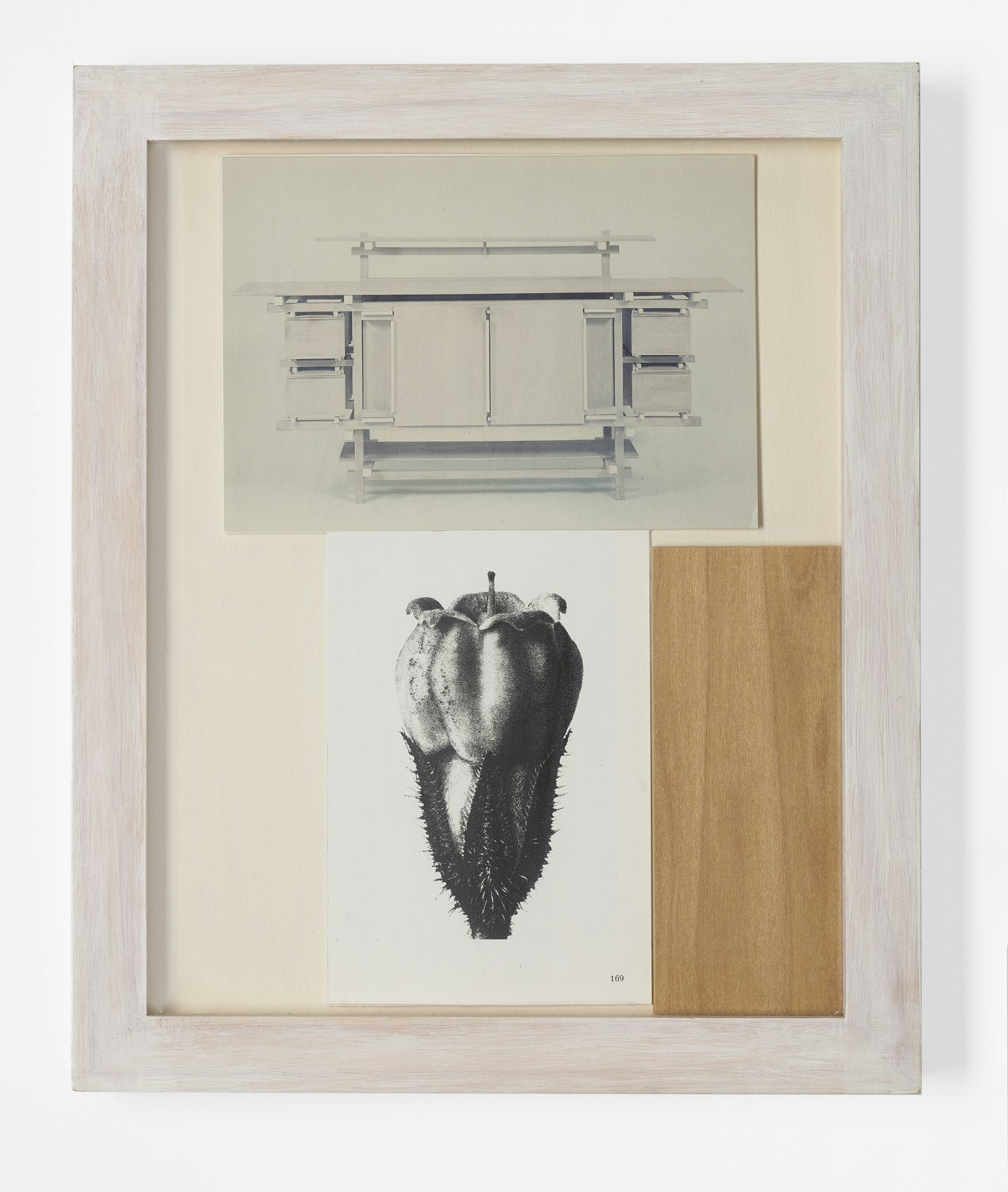

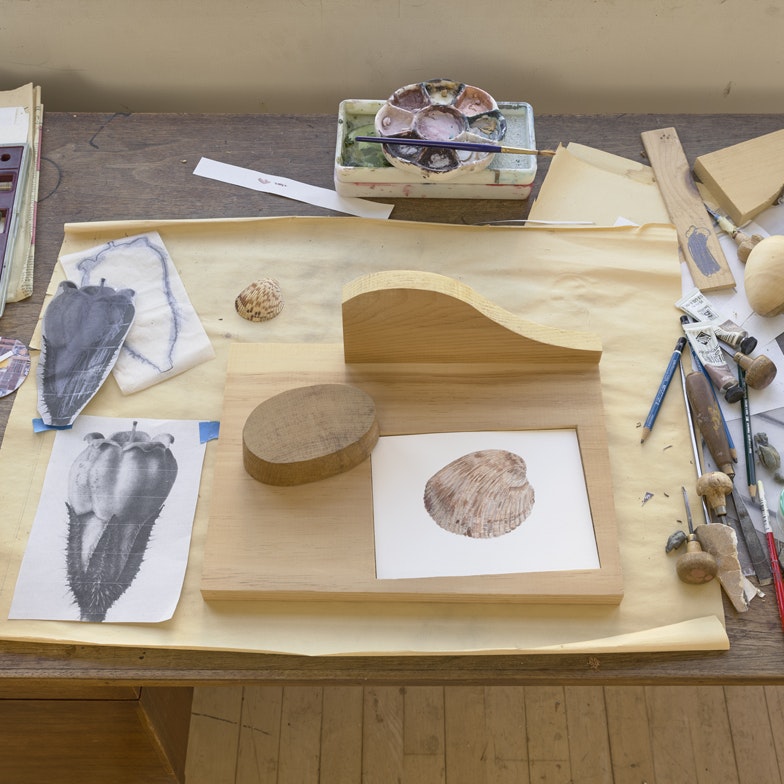

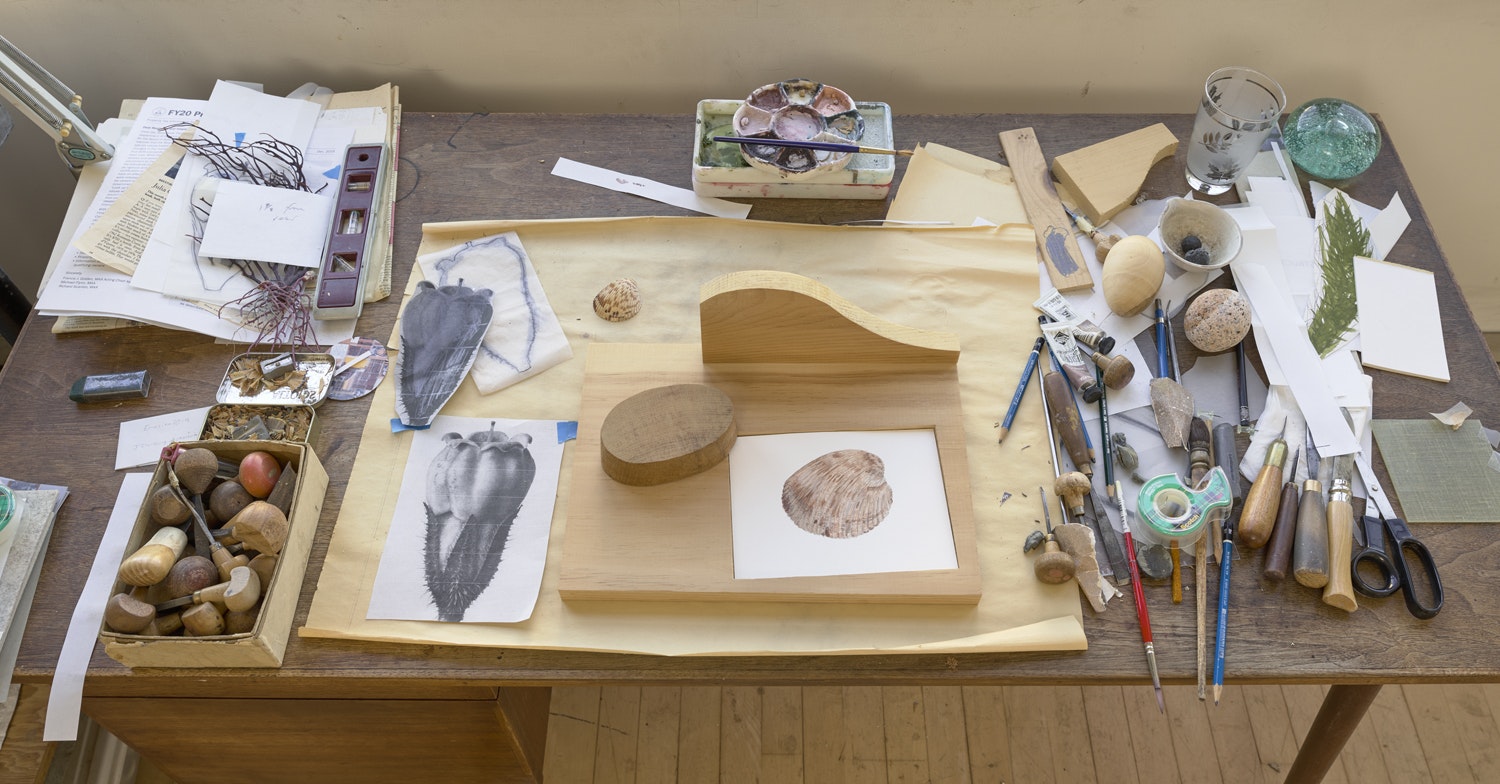

Slosburg-Ackerman is interested in joining, she says, “disparate and opposing elements—nature to artifice, crafted objects to manufactured products, high art to low culture, art to design and craft—into hybrid sculptures.” Her materials are familiar: wood, paint, paper, and organic material. In much of her recent work, she joins one item with another and uses scrap from a past artwork to complete a new work. In one corner of her studio is a series of shelves that hold a collection of chipboard boxes of uncommon sizes. Each box holds wood chips carved from a completed artwork. There is an inventory of the boxes hanging on the wall beside the shelves that records the growing collection of discarded material. The cast-offs, hidden in their boxes, are present even as they are removed from the completed artwork. Absence retains presence in Slosburg-Ackerman’s studio.

Jill Slosburg-Ackerman at work in her studio

Items in Jill Slosburg-Ackerman’s studio may not, at first, appear to be either artwork or raw material: a carved wooden burl is set perilously on a stack of boxes; natural specimens are grouped together with furniture hauled in from the street. The title for her most recent body of work, Blossfeldt-Rietveld/Slosburg-Ackerman. (An illustration. Imminent Collapse and Ascent.), refers to two 20th-century figures in art and design. Karl Blossfeldt was an artist and photographer of plants; Gerrit Rietveld was a furniture designer and architect. Slosburg-Ackerman worked for more than six years on the trio of sculptures that comprise this work, resting a cloud of pine blocks and studio scraps on top of a precarious drop-top desk, laying a field of felt on the floor, and attaching a long wooden element that mimics a horizon line. As she worked, she thought about Blossfeldt and his frustration with teaching drawing from living plant material, and about Rietveld, who stacked elements of furniture so their components seem to float. In Blossfeldt-Rietveld/Slosburg-Ackerman, the artist appears to arrest time, encouraging and halting collapse through elevation. The work is also autobiographical: it refers to her relationship with her late husband, James S. Ackerman, an architectural art historian.

Listen to Jill discuss her work

THIS IS A TRANSCRIPTION OF AN INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY SHRUTHI VENKATA WITH ARTIST JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN IN JULY 2020.

SHRUTHI VENKATAA: I’m Shruthi Venkata. I am a rising junior at the college. And I worked at Radcliffe last year, and I’m continuing working with Meg this summer. Really glad to be here and excited to speak with you. Tell us about your time at the Bunting Institute, your day to day, stand out experiences, anything.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: I am Jill Slosburg-Ackerman. When I was at the Bunting Institute -- and we were in the Schlesinger Library. That was where the Bunting Institute was. But I did a lot of research in advance, and I was extremely interested in -- then it was called primitive art. And there was an exhibition in the early 1980s that was called Primitivism. It was given by the Museum of Modern Art or hosted by them. And there was a huge response to the racist nature of that title and that category. So, I got a fellowship, and I went ready to study the tribal art collection at the Bunting Institute. And I realized how ignorant I was. So, I started reading people like Edward Said, Orientalism, a lot of Foucault. So, I was in my studio reading before I really started to work.

I was not a very good artist then. I was probably not a bad jeweler. But I wasn’t a great sculptor. And I was making the same mistake over and over and over, but I was getting educated. And at the same time, the biggest part of my education was being at work with all the other fellows. I would go in the morning. I had my dog. That was Nora, the Airedale. There have been many dogs. And we would just go to work all day and into the night.

My own work, in some ways, didn’t change much from what I had started to do. I was making things for sure, but I don’t think that that time made the work, per se. One thing I’ll mention though is that at a certain point -- probably in the teacher in me -- I thought it would be really nice to have a studio assistant. So, an undergraduate at the time named Amanda Guest became my studio assistant. And she has become a lifelong friend. She became my studio assistant after I was at the Bunting and then even when I was in New York. So, there was this other lovely, lovely relationship with someone who helped me but was also getting a certain education. And she stopped being pre-med and really concentrated on art making, and I don’t know how much I had to do with that. But maybe it was helpful for her to see somebody being an artist.

SHRUTHI: That’s a really inspiring story. I have a friendship like that with an artist (laughs) I was working with last year. I wanted to ask how the folk art you’ve produced has changed throughout the years.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN:This is hard because I -- my first training was as a jeweler and a metal smith. I really decided to -- that I need to make sculptor instead of jewelry. I was always doing a little bit of sculptor and my MFA was in sculptor. But I had a lot of problems with scale, and I was trying to find the absolute right size that the form should take in my work. And one of the things that happens when you make jewelry -- I see you have earrings on. They can only be so big. They can only be so heavy. And so, there are certain limitations that were becoming problematic for me. So that was one question. Another was that, at that time, there was this art craft argument going on. And I just thought it was stupid. But some of it was true. But I wasn’t being nourished by the kinds of dialogue that I felt were happening among -- between painters and sculptors.

The other thing is that as my work evolved, and you can see this, I was making jewelry out of wood because I could make something bigger in wood and because it would be lighter. Along with that something that became important -- and this was less of a change perhaps is that when I started making sculptor, most of those objects were tabletop pieces. So, when you make a tabletop piece, you have to put it somewhere. If you make a piece of jewelry, you just put an ear wire, and you just hang it off your ear. And there’s no problem. It’s a brooch. You put a pin back on. Put it on. No problem. But it doesn’t work that way with a piece of sculpture. So, a very big part of my search was how and where the work is sited.

That means that sometimes I was building table pieces that my work rested on. And I eventually got very involved in cast off furniture, discarded furniture, because it had a history. And there’s a lot of material culture there which I’m interested in. So then I could work with a site that wasn’t as neutral as a pedestal because I thought a pedestal was not really what I was interested in. That led to the idea of installation eventually. So that a place could provide the venue for the work.

SHRUTHI: What is your process for creating an artwork?

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: Almost every piece starts with what I call a mother drawing or a mother work. Long before I even started that sculptor, I made a collage. And that became a kind of blueprint for how I started to work or saw problems when I really started making the sculptor. And almost every work I’ve ever made has a mother drawing. And often, it isn’t a prediction of the work. But it then starts to -- I realize in retrospect it has described something really important in the work.

SHRUTHI: I have one final question.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: Okay.

SHRUTHI: tell us about your friendship with Marilyn and how it has played into your practice.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: Oh, we’ve known each other -- I think we’ve known each other about 40 years. And we met when she came to Mass Art to teach. I think our work is really, really different. I might not have sewn the felt section of the platform piece if I hadn’t been around Marilyn and all of her thread and needles. It’s a funny thing because I don’t think it’s a tangible thing that describes just how we became deep friends or the why of it. I mean I know a lot of people are thinking about friendship now. And it’s interesting to contemplate.

SHRUTHI: So, I wanted to say thank you so much, Jill, for taking the time to speak with us and sharing your personal story.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: Oh, well, thank you for inviting me. Thank you for all your work on this. And I’m so happy to meet you.

MEG ROTZEL: My name is Meg Rotzel. This interview was conducted in July 2020 with artist Jill Slosburg-Ackerman and Harvard College student, Shruthi Venkata. It was edited by Joe Zane for the online exhibition accompanying the art works of Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

END OF AUDIO FILE

Jill Slosburg-Ackerman (b. 1948) is an artist based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Slosburg-Ackerman’s metaphysical, hybrid wood sculptures, installations, and drawings made from discarded furniture, sawdust, and wood scraps emanate from an examination of natural forms and phenomena. Originally from Omaha, Nebraska, she is inspired by the pragmatism of the pioneers who settled the Great Plains, material culture, and the history of art. Slosburg-Ackerman’s work has been exhibited for 50 years in numerous galleries and museums, including at the Cohen Arts Center at Tufts University, Concord Center for the Visual Arts, the Cummings Art Galleries at Connecticut College, the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Fuller Craft Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Nightingale-Brown House at Brown University, the Rose Art Museum, UMass Dartmouth, and the Worcester Art Museum. She is a professor emerita at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, where she taught from 1974 to 2018. Her book Restless Shelves/Psychophant is forthcoming.

Anya Ventura writes in an essay commissioned for this exhibition that, “Friendship offers a model of being-with-the-other, a mode of giving and receiving, that seems unbound by ideology or common thought. Friendship resists the totalizing forces of the group. Unlike family and marriages, friendship is not regulated by law, property, or blood. Friendship requires no certificates, licenses, paperwork, or formal tests—it remains, enticingly, beyond the purview of officialdom. We choose our friends and claim them in our private ways. And if the beat of the nuclear family is set to a uniform pace, friendship maintains a far stranger tempo.

Maggie Doherty writes in her book The Equivalents: A Story of Art, Female Friendship and Liberation in the 1960s (Knopf, 2020) that in Virginia Woolf’s original formulation of a room of one’s own she reveals not only the need for privacy and solitude but also “for female community and for intergenerational support between women,” a vision Doherty claims was realized by Radcliffe with its formation of a new kind of institutional support for women. It may be possible that the Bunting was a formalization of the women’s societies that have always existed: the social clubs, sewing circles, whisper networks, etc. And this paradox—the anarchic friendship living within the orthodoxies of the institution—might be reflective of the complexities of friendship itself.”

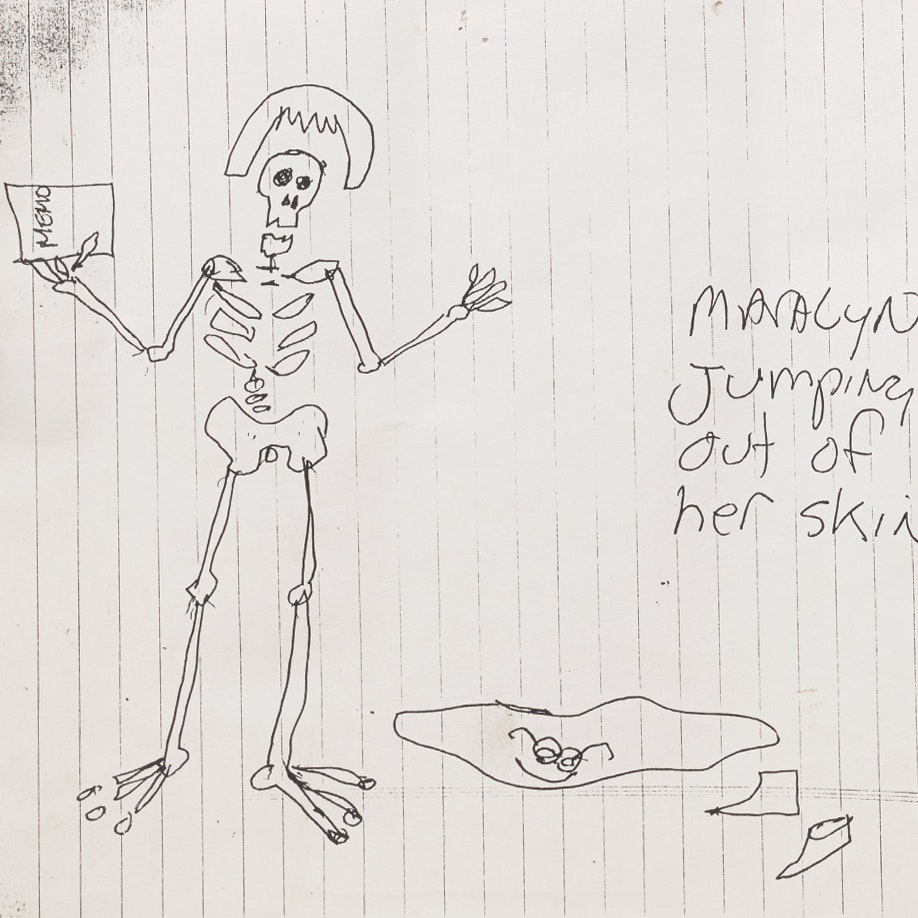

Jill & Marilyn

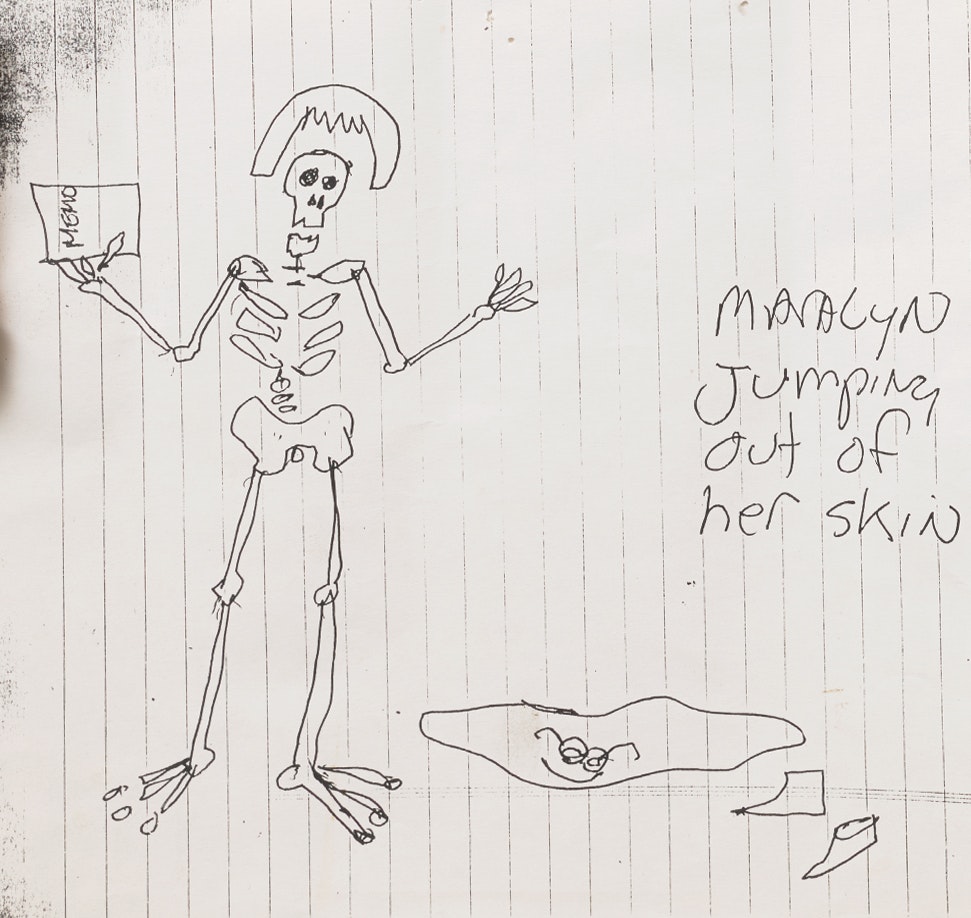

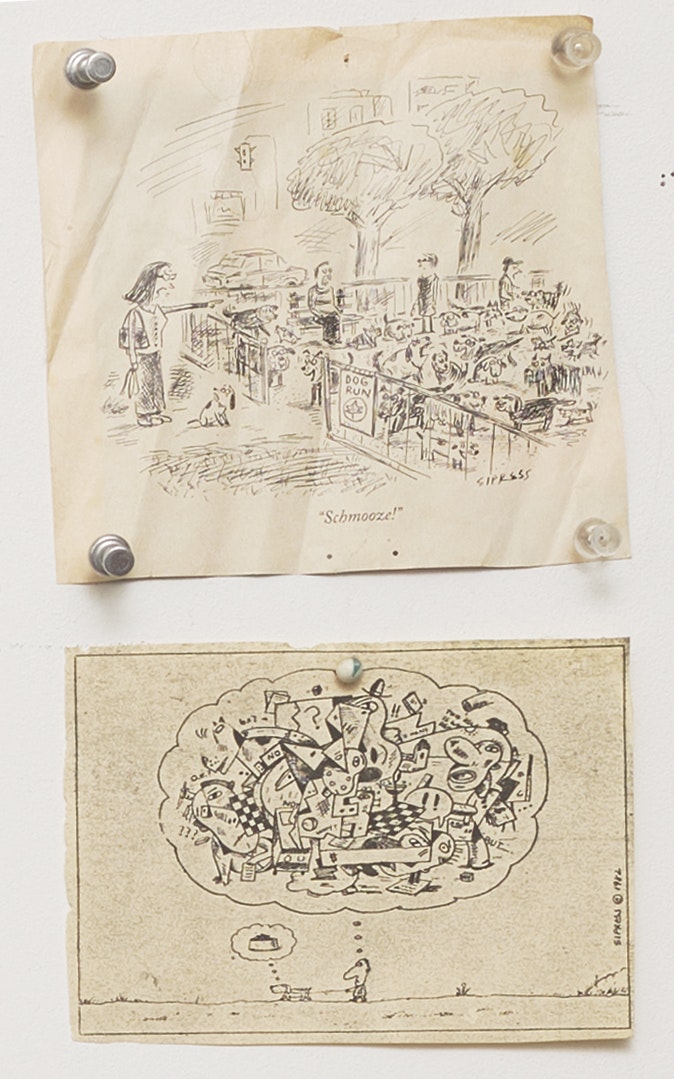

In friendship, we see a model of collectivity that isn’t based in the family or law, but in natural affinities—a mode of mutual reciprocity that resists categorization. In Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman’s shared studio kitchen, there is a collection of ephemera pinned to the wall: cartoons, announcements, a drawing of a sleek greyhound, and photographs of them together, in groups, with regalia, smiling, paired off. Decades of togetherness have created a bond that could simply be the outcome of shared circumstances: the Brickbottom Artists Association that they helped found and the Mass Art Fine Arts 3D department that they shaped through their teaching. Between themselves and the institutions they have built, Pappas and Slosburg-Ackerman have cocreated a relationship that is ordinarily extraordinary.

During the making of this exhibition, Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman were interviewed over Zoom by Shruthi Venkata, a junior at Harvard College. In response to one of Venkata’s questions, Pappas’s face lit up at the memory of the unexpected joy she experienced when she re-entered her studio following the death of her partner. This joy is profound: the fact that a woman can be in touch with the eros of artmaking throughout her long life, even in grief. Pappas’s joy is not due to her persistence alone, although that is considerable. She required community: that of the faculty meeting, the classroom, the art opening, the residency and fellowship program, the alliance of artists who create their own place. These public communities are joined by the private ones we form when we dedicate ourselves to the particular private rituals of our friendships.

This exhibition asks an unending question: How can women be together?

Pappas and Slosburg-Ackerman’s friendship tell us: We live it.

Listen to Jill and Marilyn discuss their friendship

THIS IS A TRANSCRIPTION OF AN INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY SHRUTHI VENKATA WITH ARTISTS MARILYN PAPPAS AND JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN IN SEPTEMBER 2020.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: My name is Shruthi Venkata.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: My name is Jill Slosburg-Ackerman.

MARILYN PAPPAS: My name is Marilyn Pappas.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: The first question is, how did you two meet and how did your friendship first grow?

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: Marilyn joined the faculty at Mass College of Art and all I can say is that I liked her. There was some instinct that got me interested in getting to know Marilyn. There’s more later, but that’s how we met, according to me. You know, there was something about our chemistry. We laughed all the time and that was a really wonderful thing, because not everybody does that together.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: Our next question is, what do you value in your friendship with one another as artists and as people?

MARILYN PAPPAS: Well, as artists, we have had the wonderful opportunity to be next door to each other in our studio with only a wall surrounding us. We jointly own this studio and have done so for over 30 years. It has been really easy to talk about art with each other and have critiques and try to help solve each other’s problems. It’s -- I think when an artist gets out of art school or wherever and all of a sudden you don’t have that community, but Jill and I had this little community of the two of us. And so, we were not quite as alone with our art. So, that’s been a very important part of our friendship. And then, socially, we’ve travelled together. So, we’ve had both an interesting and wonderful friendship both as artists and as women, as people.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: We took a wonderful trip to Europe together, and we saw collections of work and we experienced other cultures together. And she was the planner of those things. And we were both single, so we could do those things together and it was extremely rich and always easy and interesting. You know, I was thinking about the studio life in a friendship or relationship. In this case, Marilyn and I are witnesses to each other, and observers of each other. And there’s this really important foundation of the history of the development of the work. So, I can show her something that is brand new and it may be really bad -- we don’t judge each other, either. It’s not about good, bad, it’s about what’s working or what’s a problem. And Marylin or I can just look at -- in my mind’s eye, her mind’s eye -- everything that went before and start to understand the possibilities, the connections, the breaks with things, and that’s a very wonderful foundation. There’s so much trust. I can show her just about anything -- and respect. I mean, I can look at anything of hers, and we respect each other’s endeavors so much that it’s a very rich dialogue.

MARILYN PAPPAS: I think, too -- I’ll add just a little bit to that -- that we don’t always agree with each other and sometimes, when we look at each other’s work, Jill might give me suggestions of something I’m having -- a way to solve a problem, and sometimes I agree with her and sometimes I don’t. But that’s all right. We don’t feel as though we have to agree with each other. We can respectfully disagree. And also, we let each other have each other’s own lives. We have a life together, but we each have other people in our lives. So, I think that whole respect and trust is a really important part of our friendship, both the aesthetic part and the personal part.

SHRUTHI VENKATA: Next question is, what was one instance in which something beautiful came out of your friendship?

MARILYN PAPPAS: I can answer, first for that. I actually, when I -- there’s so many things over so many years, but two things in particular came to mind, one which affected my art, and one which was more personal, although they both were personal. The first one was about our move into Brickbottom for our studio. I had moved out of my rental studio in Fort Point Channel in Boston thinking that the studio was going to be finished on a given day. And as construction often happens, it wasn’t finished. And so, I was stuck for a while without a studio. And Jill came to the rescue. She was then living in a medium-sized -- living and working in a medium-sized loft in Cambridge. And she generously offered to put a small table in her loft for me to work on. And I accepted. And during those, I don’t know, a few weeks or months, whatever it was, I worked on very, very small collages based on my travels. Well, those pieces informed my work for years to come. So, that was pretty extraordinary. I was so grateful to Jill for her generosity and her ability, you know, to do this.

And then, the second thing I’m thinking of is more personal. When I turned 80, I got sick so we couldn’t have it. And the whole winter went by and spring, and onto the next year. But anyway, that birthday went by and a couple of months later, after my 81st birthday, Jill invited us over for dinner. And when I came in the front door of her house, Jill just met me right at the door and said, “Oh, I have to show you something in my dining room.” So, I followed her in and when I got there, there were all of my dear friends and family sitting around a big, round table yelling, “Surprise.” I said, “For what?” It didn’t occur to me that this was my 80th birthday party. Anyway, it was so wonderful of her to do it. It was a wonderful party. I loved every minute of it. And I -- well, that’s Jill. You know, she is both creatively inventive and personally, such a good, loyal friend. So, thank you, for both of those things which affected my life.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: I had a really hard time with this question, Shruthi. And I -- it was so interesting to me when you asked about something beautiful, and maybe because I’m a maker of objects, I immediately thought, “What is the thing? What is that one thing?” And eventually, I started to think about beauty in a very different way, and I’m sure that my thinking is affected by the COVID virus and the political situation as well. But I started thinking about beauty and what I have from Marilyn is certainty and security. You know, she’s always there and I don’t have to worry about it. And that feels so good. The beauty, as I think on it, is so much about a state of mind. It’s about time and the longevity of a relationship, going through so many things, so many changes, and always knowing that someone is there and being able to talk about it and work on it. And it’s the art and the good fortune of being terrified to invest in the Brickbottom Project, because we both -- we became partners because we were afraid of losing a thousand dollars to be a part of that project. But that brought us 30 years of sharing a space together, and the richness of that. So, serendipity and longevity that brought all these other gifts, is my answer, Shruthi and thank you for that, because I’m grateful and I wouldn’t have thought about it that way.

MARILYN PAPPAS: I think everything that Jill is saying is so true. We have an amazingly comfortable friendship. It just -- as Jill said, it’s there. We can depend on it whether if we need each other. We still have a lot of fun together. We like to cook. And now, Jill has this adorable dog who -- and that provides a lot of fun in our relationship. (dog barks) Oh, look, he’s talking.

JILL SLOSBURG-ACKERMAN: I don’t know what to say about it other than, being an artist requires being alone and courageous in a certain way, being very subjective. And then, there’s the career that brings in a whole other way of needing to be in the world and I feel like we’ve never gotten in each other’s way, in terms of careers. We’ve supported each other. I think we’ve always -- almost always been able to go to each other’s exhibitions, the openings. And maybe because we work in very different fields, that we’re not in competition with each other. There’s never been any hard feelings, “Marylin got into that show,” or “Marylin’s going to have this, I don’t.” So, that’s been really good, that we work in different media. So, we inhabit different worlds professionally, somewhat. But I think I mentioned earlier that I probably wouldn’t have sewn something in my recent work if I hadn’t been watching Marilyn with her needle and thread. So, there’s influence, but it’s not competition. And I think that keeps it very comfortable and peaceful and loving, and totally, 100 percent easy to be supportive.

MEG ROTZEL: This interview was conducted in September 2020 with artists, Marilyn Pappas, Jill Slosburg-Ackerman, and Harvard college student Shruthi Venkata. It was edited by Joe Zane for the online exhibition, “Accompanied: The Artworks of Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman” at the Radcliff Institute for Advanced Study.

END OF AUDIO FILE

The artists Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman join Meg Rotzel, Harvard Radcliffe Institute’s curator of exhibitions, in conversation and offer an online tour of their virtual exhibition Accompanied.

Pappas and Slosburg-Ackerman have worked in adjoining studios at the Brickbottom Artists Building in Somerville, Massachusetts, for more than 30 years. They have sustained a deep friendship through their artistic and teaching careers, parenthood, marriages, widowhood, and the challenges and rewards of being a woman in the field of art.

The online exhibition celebrates the work of these accomplished artists on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Bunting Institute, the predecessor of the Radcliffe Institute’s current fellowship program

Join the artists for a conversation marking the opening of the virtual exhibition Accompanied: The Artworks of Marilyn Pappas and Jill Slosburg-Ackerman.