Flash of Genius

Arianna Rosenbluth Changed the World Before Leaving Science Behind

A few years ago, Jean Rosenbluth was visiting her mother at a nursing home in Pasadena. The occasion was a holiday party, and Jean and her husband were seated with her mother and another couple. It came up in conversation that the man sharing the table was a history of science professor, specializing in physics.

“Oh, my mother was a physicist,” Jean said as she introduced her mother. “This is Arianna Rosenbluth.”

The professor was stunned. “Wait, the Arianna Rosenbluth?” Arianna smiled shyly and kept eating her lemon meringue pie.

Arianna Wright Rosenbluth, who received a master’s degree in physics from Radcliffe College in 1947, was one of five scientists who created the revolutionary Metropolis algorithm—the first practical implementation of what are now known as the Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods, go-to tools for solving large, complex mathematical and engineering problems.

Over the years, these methods have been used to simulate both quantum physics and markets, predict genetic predisposition to certain illnesses, forecast the outcomes of political conflicts, and model the spread of infectious diseases. It was Rosenbluth who found a way to get early computers to use the Markov Chain method, creating a blueprint that others followed.

“Arianna’s impact would last for a long time,” says Xihong Lin, a professor of biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, who used Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods to analyze a large set of COVID-19 data from Wuhan and to calculate the infectiousness of the virus. The methods have also helped specialists evaluate the effectiveness of quarantine and stay-at-home measures.

“Without Rosenbluth, I don’t think the field of Markov Chain Monte Carlo would go that far,” says Lin, referring to the role of the Radcliffe-trained scientist in enabling wide use of the tool across disciplines. “Implementation is critically important. That’s why her contribution is a landmark and really should be emphasized—should be honored.”

The paper that Rosenbluth coauthored—along with her then-husband, Marshall Rosenbluth, Edward and Augusta Teller, and Nicholas Metropolis—was published in 1953, but the algorithm’s origin story remained a mystery for five decades. In 2003, Marshall shared his memory of the achievement during a conference celebrating its 50th anniversary. The researchers developed the tool to illuminate how atoms rearranged themselves as solids melted, he said. Marshall did most of the conceptual work, and Arianna translated their idea into a computer algorithm—a task that required a fundamental understanding of physics and computer science, and also creativity.

By all accounts, Rosenbluth, who died of COVID-19 complications in December at age 93, was brilliant. She earned her PhD in physics at Harvard at 21 and in her short career worked under two physicists who went on to earn Nobel Prizes. And yet she effectively quit science in her late 20s, leaving her job at the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory to be a stay-at-home mother. She rarely spoke about her time in the lab—although she sometimes mentioned to her children how irritating it was that her ideas were overlooked because she was a woman trying to make it in a male-dominated field. Other times, she would lovingly describe MANIAC I—the Los Alamos machine that she used for computing the Metropolis algorithm.

“She was ahead of her time,” says Pierre E. Jacob, the John L. Loeb Associate Professor of the Natural Sciences and a professor of statistics in the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences, whose work involves Markov chains and probability modeling. In his syllabus, he renamed the Metropolis algorithm the Rosenbluth algorithm after reading about Arianna’s death.

“Better late than never,” he says.

Star on the Rise

Growing up in Houston, Arianna Wright was a mystery to her parents.

“Her mom and dad had this genius child, and they kind of didn’t know what to do with her,” says Mary Rosenbluth, one of Arianna’s four children. Leffie (Woods) Wright was confused by her quiet and introspective daughter, who didn’t care for fashion and rules but loved reading, especially fantasy books like L. Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz series. Mary recalls a newspaper article among her mother’s things that described Arianna as a child genius.

“It kind of struck me,” she says. “Here’s this girl growing up in suburban Houston, and she was just so different from everybody else.”

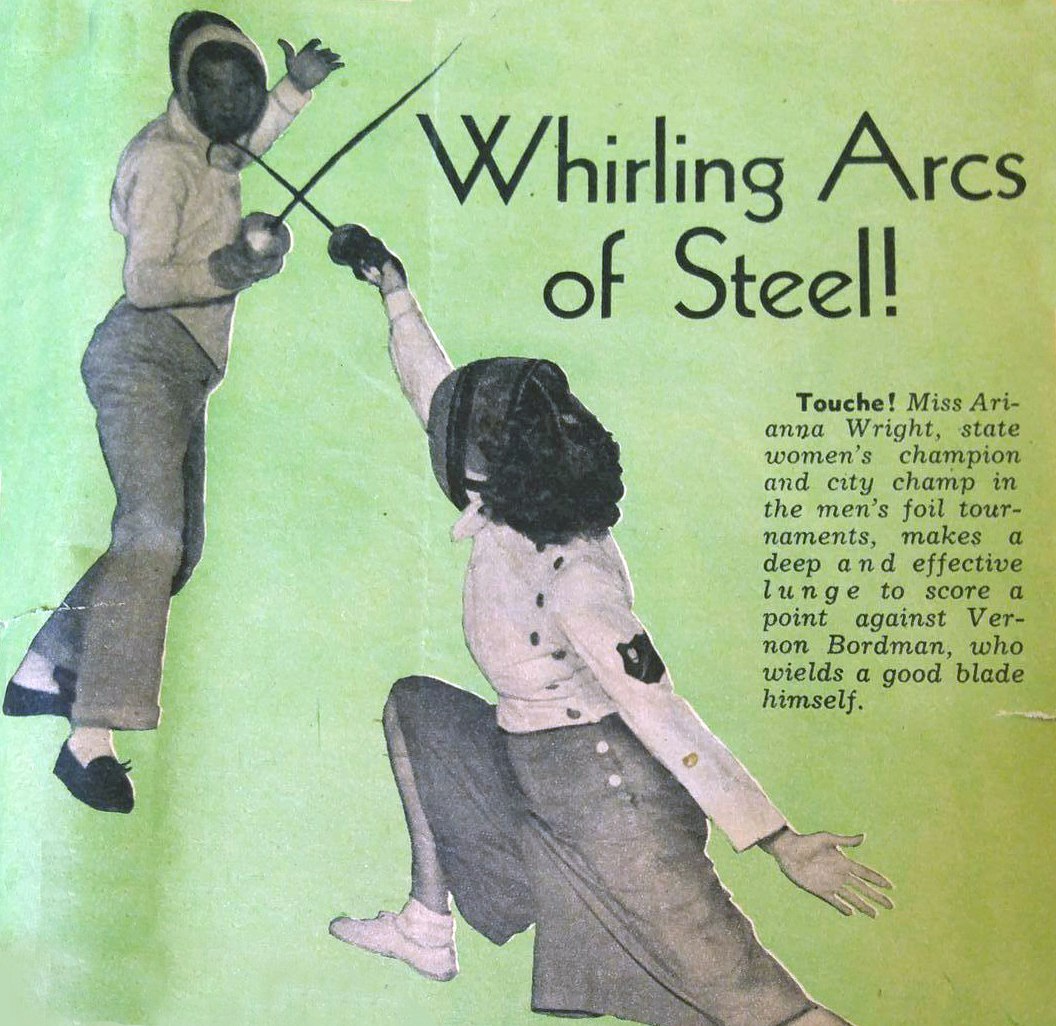

Arianna received a full-ride scholarship to Rice Institute (now Rice University) in Houston and took a bus to her classes. She earned her bachelor’s when she was 18, with honors in physics and mathematics. During her college days, she fenced against men as well as women, winning city and state championships. She qualified for the Summer Olympics in 1944, but World War II led to the cancellation of the games. She qualified again four years later but couldn’t afford to travel to London.

At Harvard, Arianna was rejected by one potential advisor because he didn’t take female PhD students, says Alan Rosenbluth, Arianna’s oldest child and a retired physicist. That was not uncommon. “Women were discouraged every step of the way,” says Margaret W. Rossiter, a Cornell historian of women in science. But Arianna forged ahead, in 1949 becoming just the fifth woman to earn a PhD in physics from Harvard.

She accepted a postdoctoral fellowship funded by the Atomic Energy Commission to study at Stanford University, where she met Marshall at a tea party. He valued intelligence in people above all, says Mary, and Arianna was clearly very intelligent. They married in 1951 and moved to Los Alamos, the national laboratory in New Mexico that was established during World War II to develop the first atomic bomb.

Los Alamos and Family Life

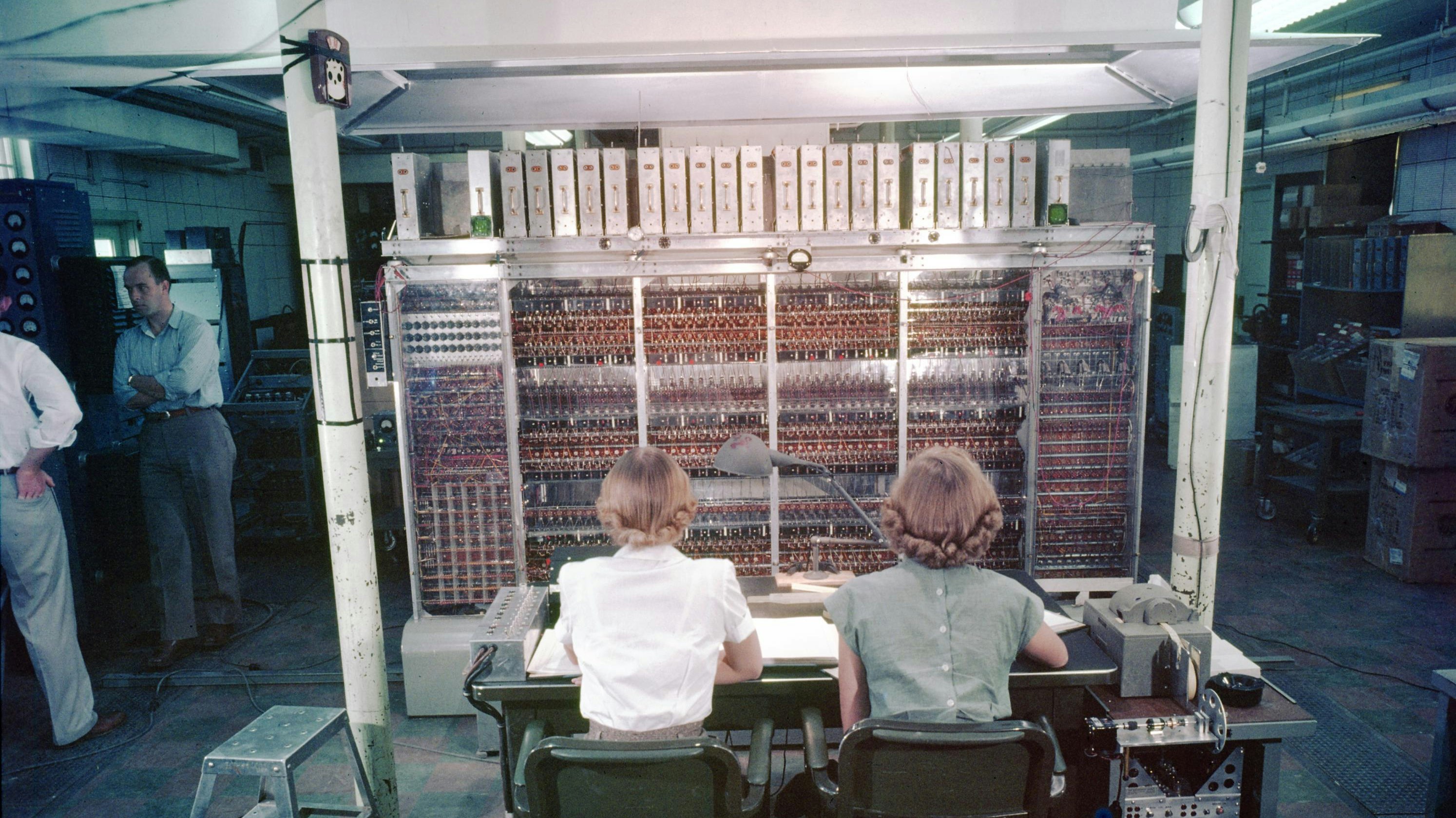

At Los Alamos, Arianna became adept at using MANIAC I, a big, fragile, and hard-to-operate machine that belonged to the first generation of computers. Computational jobs at the time were considered clerical and usually held by women. Arianna stood out.

“She had an exceptional background,” says James E. Gubernatis, a retired Los Alamos physicist who has written several articles about the history of the Metropolis algorithm. “Very few people knew how to code these machines, and fewer had PhDs.”

As Arianna developed the skills to operate MANIAC I, she worked closely with scientists to translate their ideas into something a computer could execute. Her gifts were complex and rare. To make these old machines do anything useful, says Nicholas Lewis, a historian at Los Alamos, one needed to be creative. “It’s really a testament to just how smart and inventive people like Arianna Rosenbluth had to be to get useful physics out of these very primitive machines.”

The MANIAC I at Los Alamos in 1952. Rosenbluth not pictured. Photo courtesy of LANL

In 1952, Arianna verified analytic calculations for the first full-scale test of a thermonuclear bomb—a project on which Los Alamos was concentrating much of its energy and resources. A year later, she collaborated with Marshall, the Tellers, and Metropolis on “Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines,” published in the Journal of Chemical Physics. The groundbreaking innovation at the heart of the work became known by the name of the contributor who just happened to be the first listed, says Gubernatis. The authors of the paper moved on and never used the algorithm again. Arianna became pregnant with Alan and quit her job. When an opportunity opened up for Marshall in San Diego, the couple left Los Alamos in the past.

“Here was obviously a very talented individual who didn’t really have the kind of career where that talent could be displayed,” says Gubernatis. “Unfortunately, that was the way things were at that particular time.”

Years later, when the family lived in Princeton, New Jersey, Arianna did independent research on mathematical knots. When Alan asked her if she wanted to publish her work, she said no—the thrill of solving a problem was enough. Mary remembers her mother as a voracious reader whose life of the mind extended to penetrating insights on the fiction of J. D. Salinger. “I guess we didn’t realize when we were growing up with her just how brilliant she was,” she says. “Just way above our heads.”

After her divorce from Marshall, in 1978, Arianna moved back to California, where she lived close to Jean.

“In a sense, she was a victim of the era that she was born into,” Jean says. “Women just didn’t work after they had a family. I think my mother really loved her work, and having to give it up was a big blow for her. As much as she loved her family, I think she really missed her work. I think as a result, none of us children were that close to her growing up, simply because she was not the world’s happiest person at that time.”

Still, Arianna seemed content in her later years. She read, traveled, and enjoyed birdwatching. When her health started to decline, she moved to assisted living. The letters and diaries Jean found while packing up her mother’s house went into the trash, as Arianna had instructed. “I know some people would probably kill me, but that’s what she wanted.” She also found notebooks filled with math problems and computer codes from the independent research Arianna had done over the years. Some of those Jean kept.

Anastasiia Carrier is a New York–based freelance journalist and a recent graduate from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.