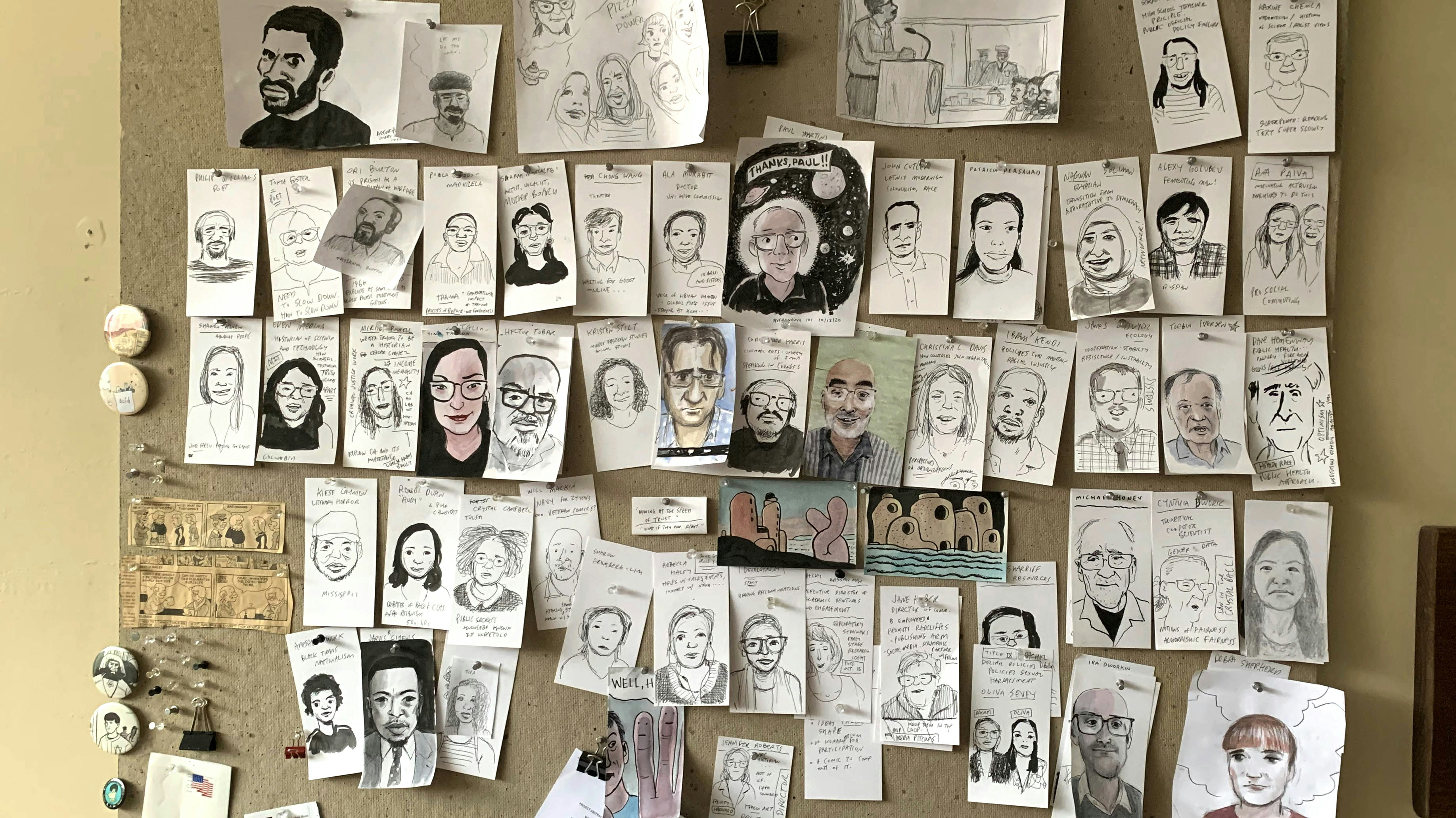

Making Faces

Zoom Portraiture Helps James Sturm Close the Distance of Virtual Fellowship

Face to face, sort of, with his virtual fellowship class, James Sturm sought a line between his two objectives: stay present and make a connection. The answer came naturally.

“It’s too tempting for me to check my e-mail or have my attention wander when I’m in the privacy of my own home,” he says. “Drawing keeps me focused.”

And so the graphic artist and 2020–2021 Mary I. Bunting Institute Fellow began to draw the faces of his classmates, a project that not only anchored him in the here and now but also helped nurture a sense of camaraderie in a year otherwise defined by absence and isolation.

“I hope all of us fellows can gather in person someday,” Sturm says. “It is a real loss that we haven’t been able, but I try not to dwell on this. I know that this pandemic year would have been that much more trying without this wonderful community.”

Taking a break from his Radcliffe project—a collaboration with student researchers on a comic focused on US healthcare—the artist answered our questions about drawing, storytelling, and fellowship. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Radcliffe: Were the drawings a spur-of-the-moment thing or more deliberate—i.e., did you go to bed one night thinking, “Tomorrow I’m going to start drawing the fellowship class”?

Sturm: At the fellows’ orientation, in September, I was meeting around 50 new people over the course of two days. I often use drawing as a memory aid, so during the initial introductions, I tried to quickly capture a few really basic distinguishing characteristics of each fellow and a word or two about their project. Beyond the drawings helping me to remember everyone, I tacked them to my studio wall as a way to forge a physical sense of this virtual community.

Radcliffe: And you’ve kept on drawing the fellows?

Sturm: Yes. If the fellowship wasn’t virtual, us fellows would be getting to know one another better in person. Now I am always in my studio when we gather, with my art supplies within arm’s reach, so it seems only natural that I’d keep drawing.

Radcliffe: How do you know what to draw? It seems to me that if you look at a person for a minute, a dozen emotions might cross their face. Which one ends up on the page, and how do you decide?

Sturm: The fact of the matter is that I am not very skilled at drawing portraits. I’m usually just struggling to achieve a general likeness, so I’m more focused on getting some basic shapes blocked into the right places. More nuanced expressions are beyond me! Sometimes I get lucky, though, and the drawing captures something essential about that person. The results can also be frustrating, but then I remember the finished drawing is beside the point. My primary intention is about giving a person my undivided attention and trying to connect to them through the act of drawing.

Radcliffe: When you’re engaged in a drawing, is there any sense of also being inside the person’s head? Are you strictly observing the person, or is there also a sense of inhabiting them?

Sturm: When I am working on a graphic novel there is a sense of inhabiting or even channeling a character. The fellows drawings, however, are strictly observational.

Radcliffe: I’m wondering about inspiration/beginnings in your work as a graphic storyteller. Is there enough in a face to get a story going? In a recent Q and A, the fiction writer and former Radcliffe fellow Elizabeth McCracken, commenting on her early work, said, “My actual stories—the ones that panned out—arrived in my head as a single sentence in a stranger’s voice.” Can you relate to that idea, when you think about your own art?

Sturm: I can. Sometimes a character springs to life in my sketchbook and begs questions that need to be answered. Stories come to me in many ways, though. Some grow slowly in the compost bin that is my sketchbook. Others, like my graphic novel Market Day, began with an evocative old photo of a rug weaver, while others, like Off Season, were born from a crisis that demanded to be unpacked.

Radcliffe: Your Radcliffe project is a comic book about the US healthcare system. What’s the difference between drawing comics and the drawings of the fellows?

Sturm: In the healthcare comic book, drawing is a form of writing. I am consciously crafting juxtaposed images to be read in a certain way to tell a specific story. I am concerned with things like visual metaphors and the consistency of the images throughout the book. With the fellows, I have no ambitions beyond the process itself. It wasn’t until I made this fellowship comic that I gave any real thought to the drawings and how they could tell any larger story.

Radcliffe: Finally, any tips for the aspiring Zoom portraitist?

Sturm: Don’t worry about using the proper tool. Whatever you draw with is the appropriate tool. Most importantly, focus more on looking at the person than where your hand is moving. If you do this your rendering skills will improve over time. You’ll also enjoy the process more if you can suspend whatever notions you have about what makes a “good” or “bad” drawing. I find I enjoy doing several quick drawings more than laboring longer on a single one. As I get to know the other fellows better, I’m hopeful my quick drawings will become more informed as I build upon our past encounters.