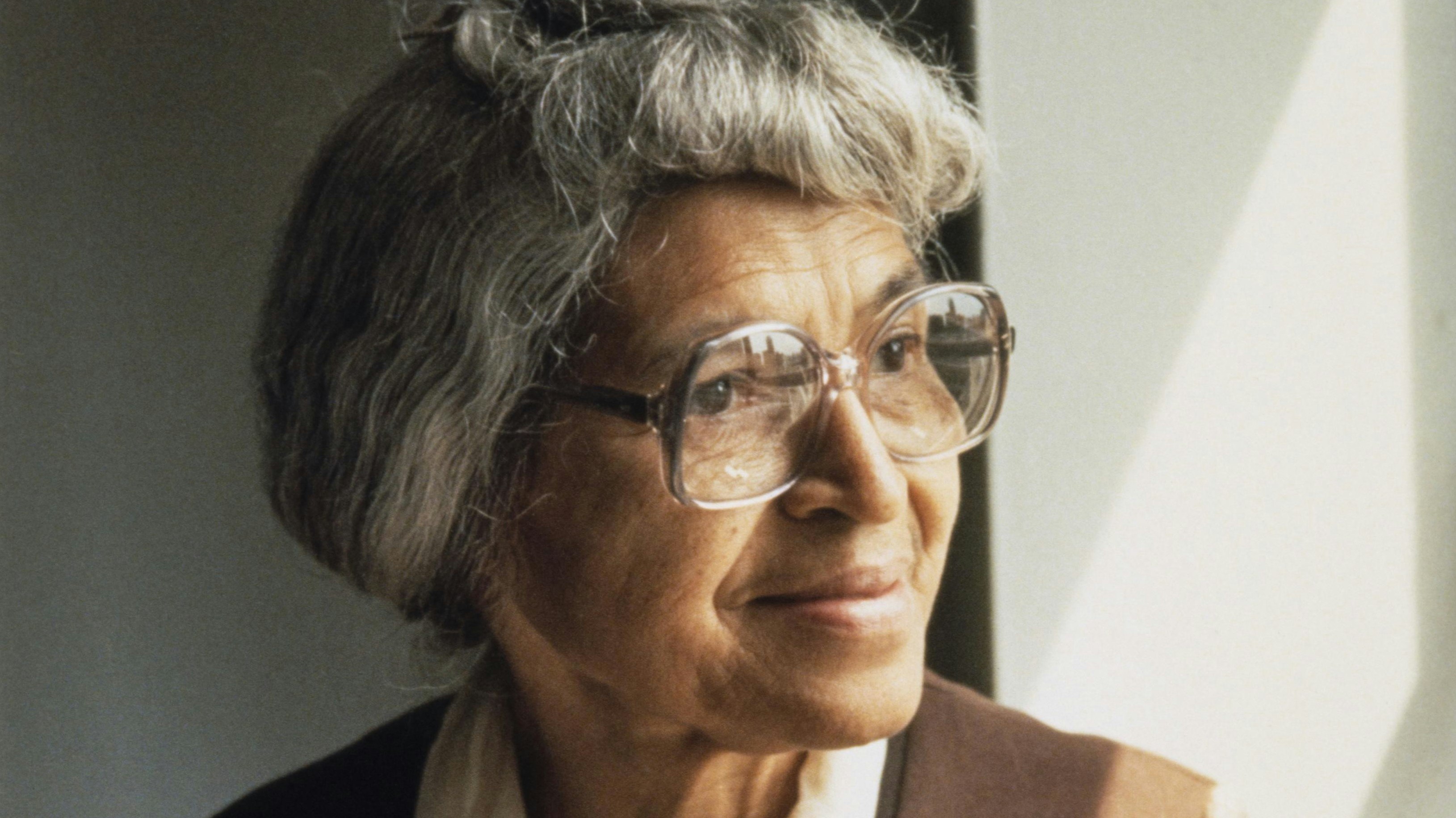

Rosa Parks Oral History Interview

Rosa Parks (1913–2005) recalls the evening she refused to leave her seat for a white man on her bus ride home from work on December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama.

Her courageous act of civil disobedience set in motion the Montgomery Bus Boycott and, a year later, the Supreme Court decision in Browder v. Gayle (1956) that ruled that Montgomery's bus segregation laws were unconstitutional. At the time of her arrest, Parks worked as a seamstress in a department store and served as secretary for the local chapter of the NAACP. Fired from her job, she stayed in Montgomery until the boycott forced an end to all dIscriminatory practices on the bus lines. In 1957 she and her husband moved to Detroit, Michigan, where in 1965 she took a part-time job as receptionist and administrative aide in the office of Congressman John Conyers. She was the first woman in 1980 to receive the Martin Luther King, Jr., Nonviolent Peace Prize.

This audio recording is part of The Black Women Oral History Project, including interviews of 72 African American women recorded between 1976 and 1981. With support from the Schlesinger Library, the project recorded a cross section of women who had made significant contributions to American society during the first half of the 20th century. The interviews discuss family background, marriages, childhood, education and training, significant influences affecting narrators’ choice of primary career or activity, professional and voluntary accomplishments, union activities, and the ways in which being black and a woman affected narrators’ options and the choices made. Interview transcripts and audio files are fully digitized.

Listen to audio recording of Rosa Parks Oral History Interview

For research tips and additional resources, view the Hear Black Women's Voices research guide.

[start of track]

Marcia M. Greenlee [MMG]:

On the first of December, 1955, you refused to give up your seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus. Your action and the subsequent developments from that action resulted in a Montgomery bus boycott, which in turn launched a new phase in the civil rights struggle. Other black passengers could have refused to give up their seats. The person next to you on the bus could have remained seated beside you. But everyone else dutifully acquiesced to the white bus driver's demand that they move. Only you stayed in your seat. Why?

Rosa Parks [RP]:

I think it was because I was so involved with the attempt to bring about freedom from this kind of thing. I had seen so much within reach on the basis of the Whitney Young experience under the same situation that I felt that there was nothing else I could do to show that I was not pleased with.... People have said that I was a great democrat, people say things like that, but I was not conscious of being...I felt just resigned to give what I could to protest against the way I was being treated, and I felt that all of our meetings, trying to negotiate, bring about petitions before the authorities, that is the city officials, really hadn't done any good at all. And as long as we continued to give them our patronage... I recall Mr. Eddie Mitchell saving that he had a committee that had gone before the bus company for the extension of the bus line to the same area and the community where most of our people lived, instead of them having to walk an hour, or whatever length of time it was...And then came the [time] to propose it, and they were told that as long as they thought...was there any need of them extending the line? This wasn't conscious in my mind at that moment, but so many incidences where I think that always make it appear that if a few of us form a committee, which [try to ] have this thing remedied...make it appear that that was what we wanted. And they were pleased that they didn't have to extend it, as long as we accepted it to be that way. At this point I felt that, if I did stand up, it meant that I approved of the way I was being treated, and I did not approve.

MMG:

Had you ever broken any segregation laws or practices previously?

RP:

I had not, to a great extent, but I hadn't...I started to think about some of the times...I, this to me...First of all, I wanted to say that at this point on the bus ride, I didn't consider myself breaking any segregation laws that I wanted...because he was extending what we considered our section in the bus. I had refused on any number of occasions to give my fare at the front of the bus, and then go around to the back to get in. That was another thing that some of the bus drivers would do. See, all of the bus drivers did not practice the same...it was not uniform. There were just certain bus drivers that would insist on you going to the back after you give him the fare. You would step up in the bus, get in the bus, and then step back off the bus and go around to the rear to enter. And neither did all of them ask you to stand up if there was white people standing. So it seemed like each driver was at his own discretion.

MMG:

And this was a zealous one that you encountered that night.

RP:

It seemed to be.

MMG:

What was the reaction of the other black people on the bus when this happened?

RP:

They didn't any of them say anything to me. Some few did get off the bus, and I know some of them asked for a transfer, and then some just got off by main door. But during the time when I was there, all remained the same exactly where they were.

MMG:

Nobody tried to interfere with what was going on between you and the white driver?

RP:

No.

MMG:

Did you resent that in any way?

RP:

No.

MMG:

Did you expect some support?

RP:

No, I didn't. It didn't even enter my mind. Because I knew the attitude of people. It was pretty rough to go against the system to the extent that you might not...There was one man who was on the bus, he lived next door to where we lived, and he could have if he'd wanted to, gotten off the bus to let my husband know that I was arrested. My husband thinks kind of hard of him for not at least telling him what had happened on the bus. Because he knew him very well. And then there was another man who got on the bus, and he got on just after me, 'cause I spoke to him as he was stepping on the bus. He asked me a few days later if I had needed him as a witness, and I said I didn't even remember...

MMG:

Did you ever find out the name of that bus driver? Was there ever any direct reference to him in the legal matters that developed later?

RP:

Oh, yes. I remember his name very shortly. His last name was Blake. I can't remember his initial.

MMG:

What does he think about the incident in retrospect? Do you remember what he said?

RP:

I can't remember exactly what he said. As far as he was concerned, it was all in his duty.

MMG:

What was your family's reaction? Your mother and brother and husband?

RP:

Well, my mother was pretty upset when I called her. She answered the telephone, and I told her I was in jail. And I don't remember exactly what my brother said to me, he was here, in Detroit, not Montgomery. I'll have to find out, better than I, if she can remember anything special. I know he was...I don't know if he was so surprised or not, but he was pretty upset, too, I'm sure. He didn't want us to...

MMG:

During any of this time, just after the incident occurred, and you were taken off and arrested, and broken arrest, yet did you ever feel fearful?

RP:

Well, it was a strange feeling because you always feel that something could...even before the incident of my arrest, I could leave home feeling that anything could happen at any time...harassment. I think the hardest days I had were when I was still working in the department store. I would see some of the people who worked in the store, and I don't know whether there was anything personal to it, I could see their attitude, the attitude they had. Some of them were very...well, they didn't say anything to me, but they were just, they'd ignore me as though I wasn't there.

MMG:

Were you ever involved with the Montgomery Improvement Association, or the boycott that followed, in a policy making capacity?

RP:

I was on the board—I'm trying to think, board of directors—and I sat in on some meetings, but I didn't have too much time to be in the actual planning. But I did for a short while. But at that time, while so much of this was being fought, and so many plans were being made, I was being invited away from Montgomery quite a bit. I don't remember—it's hard to remember now, except that I did as many as I could, if I could, and if they called on me, if they had any marching or anything, if I could.

MMG:

How did you come to Detroit?

RP:

You mean, how did I travel?

MMG:

Well, no, not that so much as what made you decide to go ahead and come.

RP:

Because my brother was living here.

MMG:

And you and your husband felt that conditions just weren't going to get better immediately where they were?

RP:

Well, they were not any too good. Of course, it was quiet before there was any disturbance or any harassment at that time. And my mother wanted to spend as much time as she could with the two of us and she couldn't spend time with him if she remained with me there. And if she left me there, then she felt uneasy, I think. Part of our..., she and my brother got together more so than I did, and found a place for us to move, for us to live, and we came.

MMG:

What was life like for you and your husband after you moved to Detroit?

RP:

Well, it was not any too easy. Well, shortly after I moved to Detroit, I was offered a job and accepted one in Hampton, Virginia, at Hampton Institute. I earned a little money, and he was working in a barber school. He didn't have a Michigan license or anything, so he had to pass the examination, be officially [licensed]. He was working in a barber school for a man of our [race], teaching some apprentice barbers the work and training them. [unintelligible]

[end of track]