The Evolution of Brown II

Brown II was conceived as a solo exhibition of new work inspired by the 1955 US Supreme Court case that followed the landmark Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision. The pandemic lockdown required the artist Tomashi Jackson and her team of student researchers to reimagine the project.

In 1954, the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education declared racial segregation in schools unconstitutional. However, the complex issue of implementation remained and a year later, Brown II came before the Supreme Court.

Tomashi Jackson, a prominent artist with local ties whom Radcliffe commissioned to do a project on campus, knew she wanted to explore Brown II after she witnessed the efforts of a coalition of attorneys, educators, and advocates to save bus service for Boston Public Schools in 2014. Then-Mayor Marty Walsh’s first budget included the defunding of BPS transportation, significantly limiting access for many children in the city, particularly in low-income neighborhoods.

Originally, Jackson’s work was intended to be a solo exhibition of new work opening in April 2020, plus a public series of three teach-in conversations to add further depth through the participants’ personal narratives. She gathered three graduate research assistants, Kéla B. Jackson PhD ’25, K. Anthony Jones MDes ’20, and Martha Schnee EdM ’20, and the group met in person biweekly for five weeks to explore archival material and to learn about major cases in education desegregation.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Before the University went virtual in March 2020, Schnee scrambled to get the team an appointment at the Schlesinger Library’s Carol K. Pforzheimer Reading Room to look at the archive of the Boston educator and advocate Ruth Batson.

“Those were the last haptic, touch-based moments, and after that we had only digital access to the archives,” says Schnee, an artist and educator who has worked in museums and in educational and therapeutical settings.

During the shift to virtual, Jackson and her team interviewed the eight attorneys, advocates, educators, and scholars originally intended to present the teach-ins. Zoom created a real-time transcript of each conversation, resulting in hundreds of pages of notes.

“It was part of a collective effort to understand research as a continuum and create these conversations across different people,” Schnee says. “We realized this was extremely exciting and possible through Zoom.”

Video conversation with Sabelo Sethu Mhlambi from the exhibition publication.

Reviewing the transcripts, the four explored how the project could evolve from its initial concept while still retaining the crucial message of how past injustices continue to affect the present. They worked together to create collaborative documents out of these transcripts, and as narrative threads emerged, the idea of creating a manuscript took shape. Rachel Vogel AM ’18, PhD ’22 was brought on as editor to synthesize the research materials into a cohesive publication. The result is a book of eight essays on different facets of education desegregation.

“As I started working with this material, it was clear that the process for this publication was very distinct,” Vogel says. “My role was to impose a structure on it, but what that meant in practice was to let it take its time and reveal itself.”

The “painstaking” process of wrangling thousands of words from each interview transcript started with identifying the main themes, then narrowing them down to a single focal point, Vogel added. The team was also mindful of how each essay would work in tandem with the others and become part of a larger narrative.

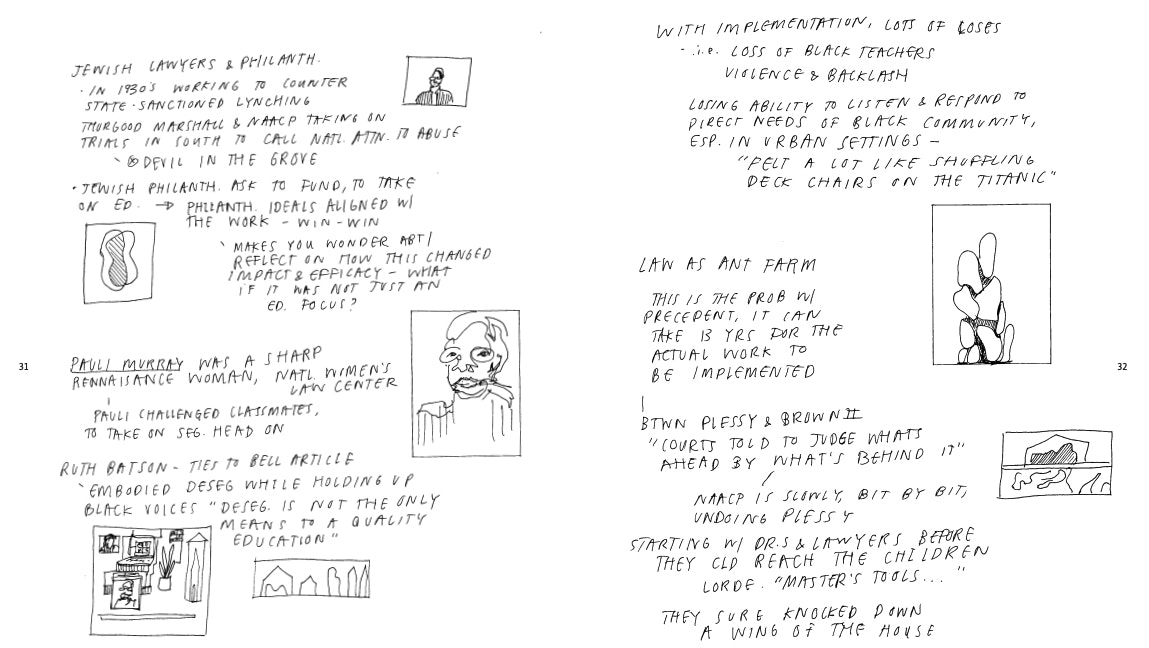

As the interviews were conducted, Schnee took notes and, as is her usual practice, sketched along with her writing. “I’m always drawing and note-taking pretty rigorously. That was something Tomashi observed, and she had this realization that it could be a big part of how we’re framing arts-based research,” Schnee says. “I sent a photo of my notebook to Tomashi and the team, and she was like, ‘Oh my God, make them bigger.’”

In the final product, Schnee’s drawings accompany each essay as a form of experimental documentation. According to a caption in the book, they “work to creatively render each speaker, their ideas, and their words in real time, mapping the trajectory of the conversation.”

“I think that note-taking and image making as research is part of the archival digging that is part of Tomashi’s work,” says Schnee. “It was a moment of opening up my notebooks and having other people see them and realizing this might be a helpful tool to process information.”

Throughout the process, Jackson requested that Schnee make the drawings larger so they could be seen more clearly. After receiving a notebook and set of pens with more space to work with, she sent Jackson practice copies for her feedback and cleaned up the final versions for typos and space. “The drawings serve as an archive, whether or not they were meant to be shared,” Schnee says. “It’s exciting to understand that this was born out of the process of interviewing these people and processing what they were saying.”

Martha Schnee, LEFT: “Desegregation is not the only means to a quality education”—Matt Cregor on philanthropy, Ruth Batson, and Pauli Murray, 2020. RIGHT: “Law as ant farm”—Matt Cregor on legal precedent and structural change, 2020.

Each of the research assistants were tasked with examining their respective interviews based on their area of expertise. Kéla Jackson’s studies as an art historian focus on Black women and girlhood, and the iconic imagery of Ruby Bridges, the first Black child to desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana, in 1960, is particularly compelling to her because of “how we come to know Black girls through that practice of image making.”

She handled the interview transcript of David Harris, the managing director of the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race & Justice. Harris’s essay covers the history of school desegregation efforts in Boston and how racial inequalities were maintained through housing policies.

The pandemic gave Kéla Jackson a different perspective on formulating art history in tandem with the project. “Art history is typically a narrative you’re trying to create,”she says. “But how do we contend with that in our history as it’s happening?” Taking artists’ methods and formal practices into account is an important part of the process, she adds. “I’ve learned from Tomashi how to be a good art historian.”

Jones was instrumental in organizing how the information was constructed and how the interviews were conducted. He created folders in Dropbox to keep all the materials accessible. Together, he and the team refined what they wanted the final publication to articulate.

“This was intended to historicize what we’d already done for Brown II, but it was also intended to be a teaching tool for the community,” he says. “People remember different things about historical moments.”

Including those varied perspectives in the final publication was vital in shaping the intended teaching tool: using the ethnographic method, it created a monograph that both serves as part of the accompanying visual exhibition and has its own utility.

Jones, a former art director working in commercial galleries in New York, has always had a foot in academia, and he respects the intellectual rigor that goes into creating art. “I was making this bridge between academia and practice,” he explains. “I’ve learned organization in trying to figure out this balance between the artist’s vision and institutional limitations.”

Jackson’s Brown II comes at a pivotal point in American history: not only was it created during a global pandemic but also during one of the largest uprisings for racial justice, following the murder of George Floyd by a police officer.

These parallels between 1955 and 2020, though 65 years apart, were especially poignant. School shutdowns threw current education inequities into sharp relief—the communities most impacted by the shutdowns were the same as those targeted by school segregation.

“One of the biggest crises of COVID was school closures. It became clear that it was disproportionately affecting Black, brown, and poor students,” Schnee says. “Schools have become resource centers for food and a place to be; when we’re asking schools to do all these things, what happens when they shut down and when they’re not resourced enough?”

Schnee adds that these inequities, although exacerbated by it, are not unique to the pandemic—but she does see clear historical parallels. In 2020, schools closed due to COVID; 65 years ago, they closed in resistance to racial integration. “The experience of working on Zoom added a significance to the work we were doing because we were talking about educational access and the barriers to it, and we were living through a potentially new chapter in the story of Brown II and its legacy,” says Vogel. “People are speaking of these COVID shutdowns as if this was the first time school closures ever happened, but in fact schools were shut down because some people didn’t want them to be integrated.”

And, in 2021, education access isn’t just about being together in the same physical space. “The piece speaks to the role of technology and how information is transferred,” Jones says. “We were able to digitally construct all of this, and we didn’t have to be in the same room.”

The team was also mindful of staying connected and supporting each other creatively and personally. “We had to rethink how these connections—with art, with objects, with people—can be made in a virtual space,” says Kéla Jackson. “There was a lot of connection we were doing as a group to hold space for each other. It took a lot of strength to continue, but it spoke to how much this project meant to each of us.” She also found value in building community amid mass tragedy and systemic injustice. For her, Brown II represented a compelling model of collective care and intentionality for building a better future.

Luckily, Jackson had the chance to continue her work and create a physical exhibition as well.

Take a brief virtual tour of Brown II and listen to the artist Tomashi Jackson talk about the making of this work. The exhibition is on view through Saturday, January 15, 2022.

“As the pandemic began to ease in the late spring of 2021, and Radcliffe was able to open studio spaces in Byerly Hall, Tomashi came back to campus and made the paintings that are now hanging in the gallery,” says Jennifer Roberts, who is the Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities at Harvard and, as then–Johnson-Kulukundis Family Faculty Director of the Arts at Radcliffe, cocurator of the exhibition.

The four paintings are based on images from the Schlesinger’s archives of Batson and Pauli Murray, both civil rights activists and key players in the fight for school desegregation. Harvard Yard also displayed banners honoring the women, which remained up through Thanksgiving.

“Tomashi is an incredible artist who has a really strong formal ability,” says Meg Rotzel, curator of exhibitions at Radcliffe. “Artists are always looking at form, they think through and create their work through the materials that are available.”

“Tomashi decided to use her time in isolation to make a much more substantial publication than we had originally planned,” Roberts says. “The publication and the paintings are now equal elements of the exhibition.” The artworks are on view through January 15, 2022, in the Johnson Kulukundis Family Gallery, in Byerly Hall.

“Key to Radcliffe and our fellowship program, we know that good things come out of being well-resourced and the ability to pivot and see where the work leads you,” Rotzel adds. “We were expecting this print project, but what we got was something different.”

Download an accessible PDF of the exhibition publication.

Register to visit the exhibition.

Lian Parsons-Thomason is a staff writer for the Harvard Gazette.