The Most Secret Garden

Of all the body’s microbiomes, the vagina’s is perhaps the least understood. In hopes of informing better therapies for vaginal health, the microbial ecologist Libusha Kelly is conducting research that could change that.

For close to a decade, the microbiome has been a hot topic of conversation in the wellness community. Any number of prebiotic and probiotic supplements have hit the market, promising to either feed or supplement the flora in the gut or on the skin, promoting a healthy microbiome. The buzz is only growing, but there’s much that scientists still don’t know.

“One of the aspects of microbiome work that is challenging is that people have really different microbiomes,” says Libusha Kelly, an associate professor of systems and computational biology and of microbiology and immunology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and the 2021–2022 Hrdy Fellow at Harvard Radcliffe Institute. “You and I are living in basically the same environment, but maybe we’re eating very different foods. On a two-week time scale, you can tremendously change the functional capacity of your microbiome by changing your diet.”

In her multidisciplinary research lab, Kelly and her team study how the gut microbiome influences drug metabolism and how viruses that affect bacteria—called bacteriophages, or phages for short—can alter microbiome function. They were able to identify enzymes in the microbiomes of volunteers that affected the metabolism of a drug used to treat colorectal cancer, opening the door to work that could help predict microbiome-drug interactions.

“People have been studying the microbiome for centuries,” Kelly says. “We’ve always known that a healthy gut is really important for a happy body, but it’s only recently that we’ve had the molecular tools to dig into what’s going on.” For example, 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing has become a common tool for bacterial identification in clinical samples.

Kelly became interested in the human microbiome after doing her PhD in computational biology at the University of California San Francisco, where she studied human genetic variation in drug transporters and how these variations might influence how different people respond to the same drug. “At that point, I was thinking, ‘Huh, you know the human genome is only part of the genome that’s in your body, right? You’ve got all these microbes that also have their own genomes,’” she remembers. She began to wonder whether the microbiome could also be involved in how people respond to drugs.

Now Kelly is hoping to apply this research to an even less-understood human microbiome: the vagina.

Just like the gut microbiome, the vaginal microbiome varies across populations and, thanks to shifting hormone levels, across life stages and even within the menstrual cycle. Although inventories conducted of vaginal flora have identified numerous bacterial taxa, “there’s been a lack of attempt to understand the vaginal microbiome as an ecosystem,” says Kelly. “Women can have very different vaginal microbiome types. If you took a vaginal swab from any number of people at Radcliffe, you would find differently structured vaginal microbiomes.”

This variation in flora complicates general statements about what makes a healthy or asymptomatic vagina—and it also complicates the efficacy of treatments for disorders such as bacterial vaginosis (BV), estimated to affect a quarter of women worldwide, usually during their reproductive years. Aside from causing pain and discomfort, BV makes women more susceptible to sexually transmitted diseases and has been linked to preterm birth and low birth weight.

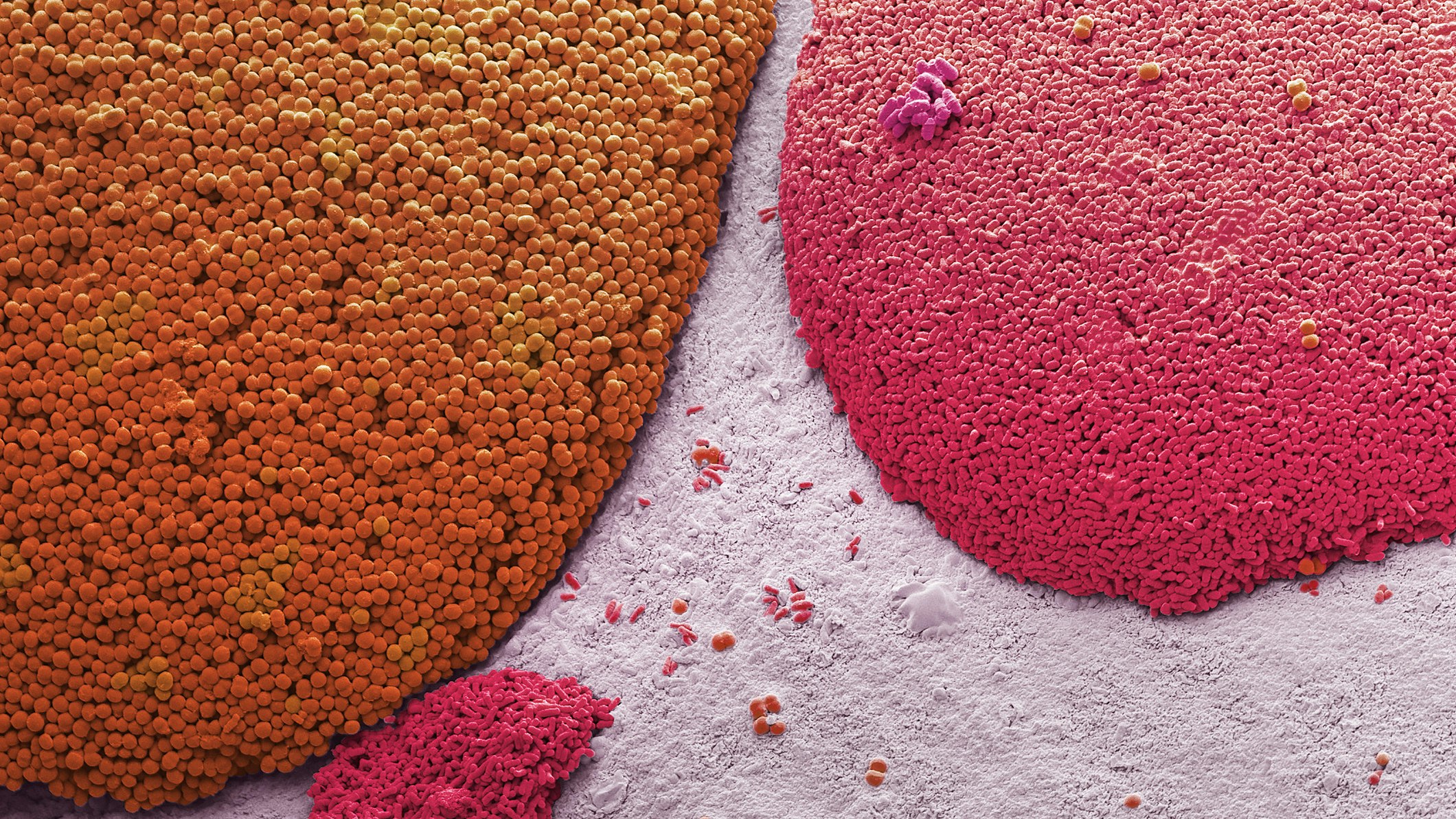

A healthy vaginal flora protects the body against urogenital infections, such as bacterial vaginosis. It is made up of many different types of bacteria, the predominant bacteria being lactobacilli. Photo by Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

“We often give people metronidazole [an antibiotic used to treat bacterial and parasitic infections], which often works in the short term and then craps out—people have recurrences, and we have no idea why,” Kelly says. Better treatments are needed, she says, which can’t be accomplished without covering the spectrum of diversity in women. “Women’s health is terribly understudied, and this is an area where we can make a difference.”

Kelly credits her postdoctoral work in the Chisholm Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with shaping her outlook on the holistic nature of the body’s microbiomes. There, she studied phages in different marine environments and found them to—rather than simply threaten their microbial hosts—play an important metabolic role. As a microbial ecologist, she prefers to think of the human body as an intricate ecosystem. “Many medical institutions still see microbes as things to kill,” she says. “They think, ‘We need a better antibiotic,’ but that’s not necessarily the best solution.”

Instead, Kelly advocates for understanding what features of the microbiome lead to either recovery or relapse, and this is what her lab is now undertaking. Collaborating with the lab of Betsy Herold, a professor of pediatrics, of microbiology and immunology, and of obstetrics and gynecology and women’s health at Einstein, her lab isolates microbes and analyzes microbiomes from vaginal swabs from women before, during, and after metronidazole treatment, with an eye toward the impacts of pH and phages, in an effort to understand whether certain types of women are more or less likely to respond to that treatment.

“We’re interested in these viruses that kill bacteria, and whether they play a role in someone’s recovery from BV,” says Kelly. “In the short term, I would consider it a huge win if we could start to figure out who can best use the treatment we already have.”

That’s not to say that Kelly doesn’t have ideas about how vaginal health could be managed going forward. She envisions a future in which, with patient permission, any gynecologist could collect a vaginal swab to be sequenced—establishing, for example, that individual’s vaginal community subtype. Such a baseline would be useful to a patient in thinking about changes in their body.

“The overall goal of this research is to benefit as many women as possible—but it’s also important to communicate what we’re trying to do as a field,” Kelly says. “I really want to make my microbiome research more accessible to people, and to help people understand how to help themselves.”

Some of Kelly’s interactions while discussing her work with the public suggest there’s much work still to be done. She has been approached by highly educated people who, desperate for answers, have a worrying misunderstanding of the science. One father wondered whether his son’s autism would be less severe if he had administered probiotics, and a woman who gave birth via C-section asked whether depriving her baby of the flora in the birth canal could have serious implications.

“I don’t want people to feel like they’re somehow failing by not using the microbiome, and I feel like there is too much of this garbage in the media right now,” says Kelly. “It’s frustrating, because I feel that women, especially, are blamed for everything they do, and I don’t want the microbiome to be misused that way.”

Kelly worries that misconceptions about the microbiome are rampant among people desperate for answers to their medical issues. Photo by Kevin Grady

In addition to spinning up new collaborations to further her lab’s work, Kelly is looking to do some deep thinking during her fellowship year about approaches to conducting basic research. “One of the things that I want to do here is learn more about how to help make this nascent field of basic and translational research more relevant to all people and less impacted by the sexism and racism that can be unfortunately prevalent in research,” she says.

With more women like Kelly in the scientific trenches who are willing to correct misconceptions—and to push for representation—the microbiome may yet inform more accessible, holistic treatments for all.

Read about Libusha Kelly's nontraditional path to basic science.

Ivelisse Estrada is the acting editor of Radcliffe Magazine.