The Prison as Petri Dish

COVID-19 has ravaged US prisons, but health care within the correctional system was broken before the pandemic—which puts more than the imprisoned at risk.

“At this point we are all sick,” writes Holli Wrice, imprisoned at FMC Carswell, a federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas. “It’s so much coughing, hacking clearing of throats, fever chills, etc.”

She is confined in Carswell, the federal prison for women who have chronic and terminal health conditions requiring special medical attention. But medical care, advocates and family members have long attested, is often inadequate, if not fatal. Now, Wrice and others say, things are even worse in this unending age of COVID.

Across the United States, 34 of every 100 people locked in prisons have tested positive for COVID, a rate nearly four times that of the general population. Public health officials have repeatedly said the inability to social distance in prisons, jails, and detention centers—many of which are at, near, or over capacity—have made these facilities petri dishes for COVID. That proved true as outbreaks flared behind bars.

According to the New York Times, by April 2021, more than 661,000 incarcerated people and staff in jails and prisons had contracted COVID. At least 2,990 have died.

Experts note that these numbers are likely a drastic undercount, given that testing and reporting vary by agency and nearly half of the nation’s jails and prisons did not report COVID data.

“Even the agencies that do report COVID data to the public often define the variables in ways that are confusing, misleading, and generally unclear,” said Joshua Manson of the UCLA Law COVID Behind Bars Data Project. “It obscures the data and obscures the reality of COVID in their facilities.”

In summer 2021, even as the Delta variant surged, some systems, including Florida and Georgia, stopped reporting COVID cases altogether.

FMC Carswell holds 994 women, all of whom have chronic or terminal medical conditions. In early January 2022, Wrice sent a prison e-mail stating that the prison’s medical staff had ordered women with flu-like symptoms to be tested. Those who tested positive were told to pack their belongings and carry them to a quarantine unit. Others were moved from one housing unit to another while others reported to their prison jobs each morning, each movement bringing with it a multitude of possible COVID transmissions.

By mid-January, Carswell reported 316 active COVID cases, the second highest number in the entire federal prison system, which had a total of 9,020 active COVID cases. Another 43,427 had recovered from COVID. At least 279 prisoners had died.

In Minnesota’s MCF Shakopee, Zhi Kai Vanderford, a 54-year-old trans man, thought he had bronchitis. The prison’s medical clinic was closed for New Year’s, so Vanderford self-quarantined until it reopened two days later. When it did, he tested positive for COVID and was quarantined in the prison’s disciplinary segregation unit, normally used for those who break prison rules.

“I felt like a horse kicked me in the chest,” he recalled. By mid-January, when he was released from isolation, another 85 of the prison’s 432 incarcerated people (nearly 20 percent)—including Vanderford’s 88-year-old friend Ardelle Manthey—had tested positive.

In California, where the US Supreme Court ruled that overcrowding interfered with the prisons’ responsibility to provide adequate medical care, nearly 8 percent of its 97,503 state prisoners has tested positive for COVID within a scant 14 days, causing weeks of lockdowns that confined people to their cells nearly 24 hours a day.

“Epidemic Engines That Multiply and Spread Sickness and Death”

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the dire connections between public health and incarceration, which are frequently treated as separate issues. US jails detain approximately 700,000 people at any given time, while prisons confine more than 1.2 million people.

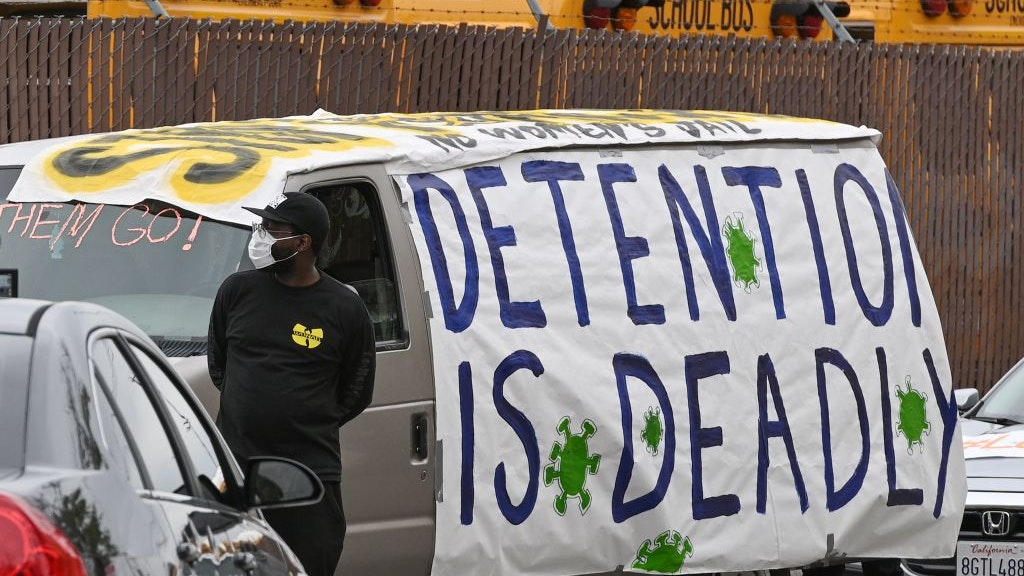

Eric Reinhart—a medical and political anthropologist, physician, and researcher in the Data and Evidence for Justice Reform program at the World Bank who recently received a Radcliffe Engaged grant—calls jails, prisons, and ICE detention centers “epidemic engines that multiply and spread sickness and death throughout broader communities.”

Each day, staff members enter and leave while incarcerated people are processed or released. Each movement brings the potential for transmission and outbreak, not just within prison walls but in surrounding communities, noted Reinhart.

During 2020, the first year of the pandemic, the Prison Policy Initiative found that prisons and jails contributed to more than half a million—or roughly 13 percent—of additional COVID cases across the United States. In a separate study, Reinhart and the economist Daniel Chen found that one in six of Chicago’s COVID cases could be traced to the Cook County Jail.

This is not the first time that an epidemic has festered behind bars before spreading to the larger community. Reinhart points back to 1990s post-Soviet Russia, where incarceration increased by over 50 percent, largely for petty crimes caused by poverty and the dismantling of the welfare state. The country also experienced multiple simultaneous tuberculosis outbreaks, which quickly spread in the country’s packed jails and prisons. For people diagnosed while incarcerated, treatment was interrupted upon release, leading to the development of a form of multidrug resistant tuberculosis, which exploded throughout Russia and then to eastern Europe between 1991 and 2001. Over 117,000 new cases were detected in Russia in 2009 alone, the equivalent of 82.6 cases for every 100,000 people.

The United States has a more robust public health infrastructure, preventing similar epidemics of tuberculosis. However, the nation’s consistently high incarceration rate has led to the spread of other infectious diseases, such as HIV, hepatitis C, influenza, and pneumonia throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Even in periods without epidemics and pandemics, Reinhart noted that high incarceration rates have been tightly linked to higher mortality rates from other diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease.

Signs pleading for help hang in windows at the Cook County Jail in April 2020. Research by Eric Reinhart and the economist Daniel Chen found that one in six of Chicago’s COVID cases could be traced to that complex. Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

An Ad Hoc and Substandard Approach to Health Care with Little Oversight

Even before the pandemic, medical care behind bars was, at best, largely inadequate and, at worst, life-threatening or fatal.

Incarcerated people are the only US residents with a constitutionally guaranteed right to medical care. In Estelle v. Gamble (1976), the US Supreme Court ruled that prisons that showed “deliberate indifference” to incarcerated people’s serious medical needs violated the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. However, the court did not specify the quality of care to be provided.

“Correctional health care is not subject to oversight by state health departments or the Centers for Disease Control,” said Homer Venters, the former chief medical officer of New York City’s jail system, a current federal monitor for correctional health care, the author of Life and Death in Rikers Island (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019), and a recent participant in “Decarceration and Community: COVID 19 and Beyond” at Radcliffe. In an interview with Radcliffe Magazine, he stated that the lack of oversight has resulted in an “ad hoc and substandard approach to health care.”

Accessing medical care behind bars is a time-consuming and often frustrating process. Jails and prisons require approval for any movement outside a person’s designated area. Instead of walking to the medical clinic, a person must submit a sick call slip or a form requesting to see medical staff. Wait times may be two or three days, sometimes over a week. Sometimes the person is never called and must fill out another form and wait even longer.

When finally at the clinic, the patient sees a nurse who evaluates their concerns and decides whether they can see a doctor. Incarcerated people have repeatedly reported that their medical concerns are often dismissed and they are sent back to their cells without seeing a doctor.

In 17 states, prisons manage their own medical services. Another 20 states contract with private corporations to provide prison medical care, while 8 states utilize both private corporations and state employees.

On the local level, more than 60 percent of the country’s largest jails utilize private health care companies. A Reuters review of deaths in US jails found that jails that relied on private health care contractors had higher death rates (18 to 58 percent higher, depending on the company) than those in which medical services were run by government agencies.

Co-pays further obstruct medical access. Forty states (and the federal prison system) currently charge co-pays to prisoners, ranging between $3.00 and $5.00 to as high as $13.55 per medical appointment. Compared to outside co-pays, these numbers seem miniscule. However, prison jobs typically pay pennies per hour, making these co-pays the equivalent of $200 to $500 outside of prison and deterring people from seeking medical care.

This has resulted in worsening conditions and, in some instances, mass outbreaks. In 2003, the CDC identified co-pays as a factor that contributed to a mass outbreak of MRSA (Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) in Los Angeles jails and in Georgia and Texas prisons.

During the pandemic, 10 states suspended all prison medical co-pays (although three have since reinstated them). Twenty-nine other states suspended co-pays only for COVID- or flu-like symptoms.

“What’s clear is that these were health systems that were failing even before COVID,” said Venters. Those failures reverberate in the outside world as hundreds of thousands are released from prisons and jails each year, often in worse health, and become the responsibility of insurance carriers and community medical systems.

Punished for Being Sick

People incarcerated in multiple states have reported hiding or not reporting COVID-like symptoms for fear of being placed in solitary confinement, in which they are locked alone in a cell at least 23 hours each day with virtually no human contact.

That fear is not unfounded. “Even before COVID, when we identified people with health problems behind bars, the response is often a punitive one,” said Venters, noting that it was common for people in the midst of a medical or mental health crisis to be isolated rather than treated. “With COVID, we’d see people tossed into a cell by themselves. It might be called medical isolation, but they don’t get meaningful health care and experience all the negative effects of being locked away by themselves. It’s a strong disincentive to report symptoms.”

Behind bars, medical staff face the dilemma of dual loyalty, or the magnified influence of the facility’s security apparatus on health care. Venters notes that this ranges from security personnel, such as sheriffs or officers, making decisions about who accesses treatment to influencing medical staff not to report injuries, chronic conditions, or self-harming behaviors. “During COVID, this means that sick people get sicker instead of getting the care they need,” Venters said.

On the administrative level, jails and prisons often lack electronic medical records or the infrastructure to track incarcerated people’s hhealth needs, including their vaccination status. Each state has a vaccination registry, but Venters notes that more than half of the nation’s jails and prisons do not cross-check the status of those entering the system. “If you don’t do that, then you don’t keep track of who needs an initial vaccine, a second shot, or a booster.”

Decarceration as a Frontline Public Health Measure

“Decarceration should be at the front of the line of public health measures,” said Reinhart. “This is a basic public health measure that we’ve needed for decades. This is not just about a pandemic response. This is about pandemic preparedness and prevention.”

He is not alone in this assertion. At the start of the US pandemic, health experts urged jails and prisons to decarcerate—or decrease the number of people behind bars. In some cases, it worked. In Chicago and New York City, the number of people sent to jail while awaiting trial decreased dramatically. In California, where the prison system was at over 130 percent capacity, Governor Gavin Newsom announced that the state would release 3,500 people who were within two months of their release dates. Kentucky governor Andy Beshear commuted or reduced the sentences of approximately 1,000 people, allowing them to be released early.

New Jersey passed the Public Health Emergency Credit, allowing people with one year left on their sentence to be released up to eight months earlier. On November 4, 2020, the day the law took effect, 2,258 people were released. The law allowed for the early release of 5,343 people in one year, a 42 percent reduction in its prison population.

Despite these seemingly large numbers, a 2022 report by the Prison Policy Initiative found that, overall, states and the federal government released fewer people in 2020 than in 2019 (531,469 versus 588,559) and that, after July 2020, the numbers of people in jail began increasing to near pre-pandemic levels. Furthermore, deaths in prison increased 46 percent (or 1,930 more deaths than in 2019). In at least eight states, 2 percent of “releases” were actually deaths while in custody.

“We need to have large-scale decarceration,” said Reinhart. “The US holds over 20 percent of the world’s incarcerated population in really bad conditions. We will have new pathogens in the future that may be even more dangerous and spread more quickly. If we don’t change that system, we put the entire global biosecurity apparatus at risk.”

Victoria Law is a freelance journalist who focuses on the intersections of incarceration, gender, and resistance. She is the author of Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women (PM Press, 2009) and “Prisons Make Us Safer”: And 20 Other Myths about Mass Incarceration (Beacon Press, 2021) and the coauthor, with Maya Schenwar, of Prison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular Reforms (The New Press, 2020).