The Story of His Life

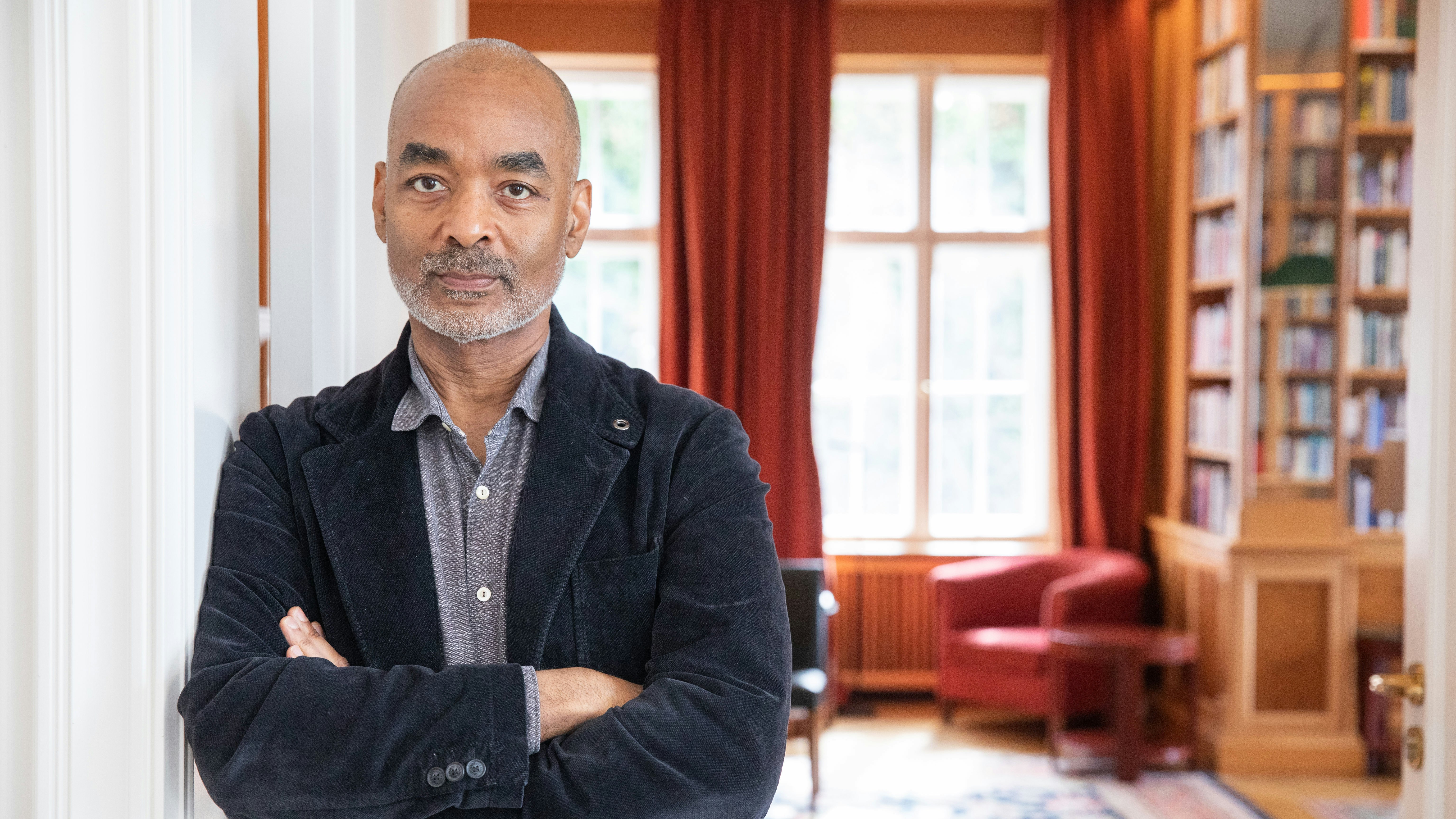

James Baldwin Was a Revelation for Robert Reid-Pharr. Now He’s a Subject.

Robert Reid-Pharr devoured science fiction as a teenager growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina, till James Baldwin opened his mind to the truly otherworldly.

“Stunning,” says Reid-Pharr, 2020–2021 Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Fellow, reliving his earliest reaction to Go Tell It on the Mountain, Baldwin’s 1953 coming-of-age classic. The novel was waiting for him—just for him, it felt like—at Meredith College, which in 1979 hosted a convention of the Tar Heel Junior High Historians. On break from the event, Reid-Pharr stopped at the campus bookstore, planning to take home some sci-fi with the $5 his mother had added to his lunch money. But it wasn’t Robert Heinlein that caught his eye.

“I’d never seen a book with a Black person on the cover,” he says.

The image drew him closer, the words carried him away.

“I don’t think I’d ever read a book in which there was a Black character, period. Remember, I’m reading sci-fi, so I’d barely read anything in which there were human beings. I didn’t understand reading as having a relationship to the actual world.”

The Pentecostalism of Baldwin’s story hit the son of religious parents where he lived; for a 14-year-old edging toward his own sexual awakening, the narrative’s homoeroticism, on reflection, charged the experience with intimacy. “It was like this book had been written directly toward me,” Reid-Pharr says. When he shared his excitement with his English teacher, she urged him on—Giovanni’s Room, Another Country, The Fire Next Time—and suggested he respond to Baldwin’s work in his class-journal assignments, instilling a critic’s sensibility. His family and friends couldn’t have been happier: fewer Martians (or so they imagined), more literature. “They were like, ‘This is good; this kid’s getting into this famous writer,’” says Reid-Pharr, smiling at the memory of his teenage nose buried in Baldwin’s ever-sophisticated, sometimes-racy prose. “So people gave me not only Baldwin, but Richard Wright, Martin Luther King, Eldridge Cleaver.”

The Harvard professor who returned to Baldwin, in the form of an in-progress biography, remains connected to the boy. “It became a moment that was decisive. It changed my life and put me going in one direction versus another.”

Among the important early stops was the Charlotte Observer, where Reid-Pharr, as a high school student considering a career in journalism, worked first as a copy carrier and then on the obituaries desk. In a loud and frantic environment, under deadline pressure and exacting standards, the novice learned on the fly, just as Baldwin had, barely out of high school, penning book reviews for the New Leader, in Greenwich Village, in the 1940s. Reid-Pharr departed the newsroom, bound for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, schooled in the virtues of compression and precision and preprogrammed against the vicissitudes of the muse. “I don’t need to go off into the woods and lose myself in order to write. I can write anywhere, if necessary. I have a no-nonsense attitude about it.”

But no amount of discipline could solve the college student’s core problem: What kind of writer do I want to be, anyway? Not a journalist, he realized, and definitely not a poet or a novelist: “I don’t think in that way; I’m not moved in that way.” When his guide arrived, she came from the future. In a women’s studies class, decades before crossing paths with Drew Gilpin Faust at Harvard, Reid-Pharr read her biography of the 19th-century politician and slave owner James Henry Hammond. The book “was good and interesting, and I could believe it,” he remembers. Faust had created a portrait that preserved the spontaneity and intrigue of real life, whetting her readers’ curiosity where some writers would have blunted it.

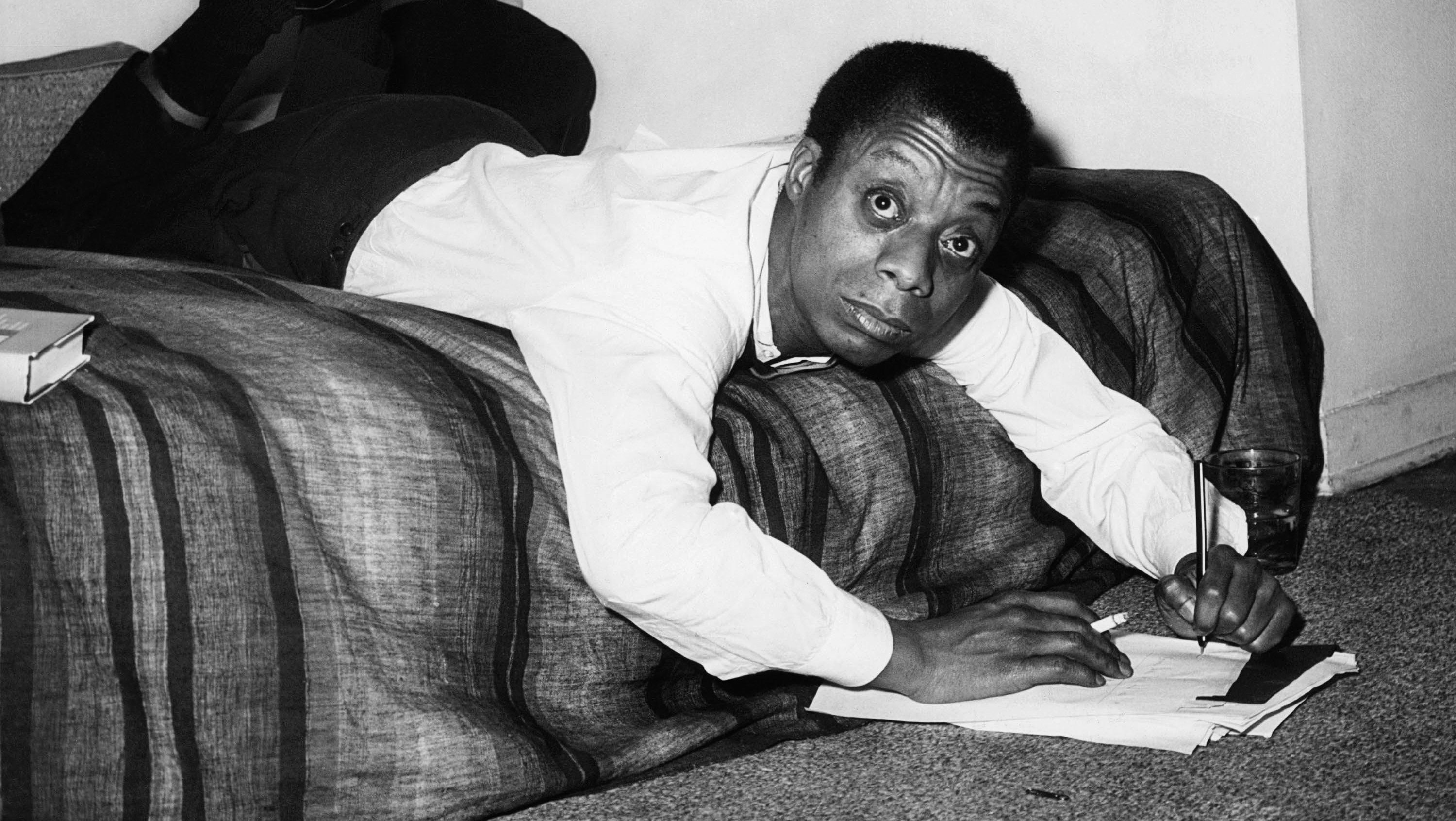

James Baldwin in 1963. Photo courtesy of CSU Archives/Everett Collection

“I don’t know that I would have had the temerity to say that I could do that—I still don’t know that I could do that—but I had this sense of wanting to know how,” says Reid-Pharr. “I wanted to know how to make that ‘aha!’ experience on the page. It was the first time I thought that there are forms of being a creative person that I can do and that are compelling to me.”

Scholarship and teaching felt like the most potent expressions of his creativity. In 2016, two years before leaving the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for Harvard, Reid-Pharr won a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation, whose chairman, Bill Kelly, was also director of the research libraries for the New York Public Libraries, one of which is the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Kelly had known Reid-Pharr for years and treated his friend to a celebratory drink. He also had any idea. The Schomburg Center, Kelly said, had just acquired a rich trove of Baldwin’s papers, and wouldn’t it make sense for Reid-Pharr to take a look at them? As in, a really close, possibly inspiring look?

“I decided at that moment, ‘OK, this is the person responsible for a big portion of the life path that I’ve taken. I see this opportunity, and I’m going to seize it.’

Another word for destiny: typing. Reid-Pharr has transcribed hundreds of pages from the Baldwin material at the Schomburg Center, which doesn’t allow photocopying. After the pandemic shut down both the Schomburg and Reid-Pharr’s secondary Baldwin archive, Yale’s Beinecke Library, an epic grind took on the glow of salvation. “The very, very good news was that I had this shadow archive. I wanted to spend my time doing more collecting, but I’d done much of it. And so, I was just going to use the materials on hand and do what I could do. COVID has not stopped the composition. I’ve drafted a significant portion of it.”

James Baldwin, in an interview with the Paris Review in 1984, three years before his death: “You want to write a sentence as clean as a bone. That is the goal.” In pursuit of that sentence, “you work like hell,” Reid-Pharr says. And then you do it again—and again, and again. Who would grudge the writer his dreams? “My fantasy is to go into the subway in New York City and get on at 14th Street and get off on 125th Street, and see someone reading the biography and forgetting that they’re on the subway. That’s what I want. And I think I can do that.”