Out for Blood: Feminine Hygiene to Menstrual Equity

Throughout the 20th century, the marketing and design of menstrual products often stigmatized menstruation as an unmentionable bodily affliction. Menstruation was wrapped in euphemism: that time of the month, a weakness, a nuisance. “Feminine hygiene” products offered sanitation, invisibility, and freedom—but at what cost? Out for Blood: Feminine Hygiene to Menstrual Equity shows how marketing and social norms around menstruation create a cultural construct with power to shape people’s lives.

The Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study gratefully acknowledges the Helen Blumen and Jan Acton Fund for Schlesinger Library Exhibitions, which is supporting this exhibition.

Exhibition organized by Lee Sullivan, Head of Published and Printed Materials

Exhibition Committee Members:

- Marylène Altieri, Curator of Published and Printed Materials

- Erin LaBove, Cataloger, Published and Printed Materials

DIGITAL EXHIBITION

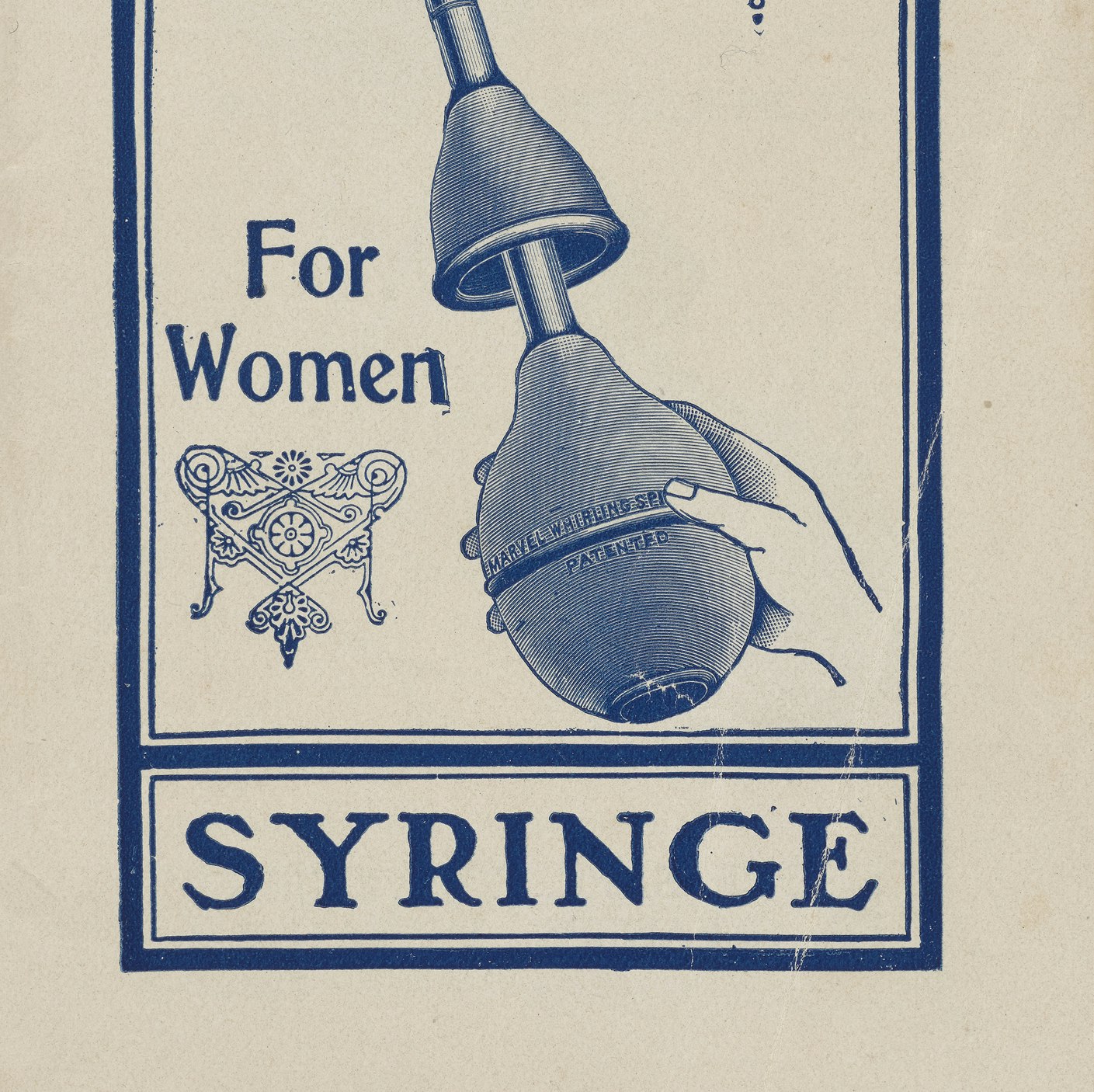

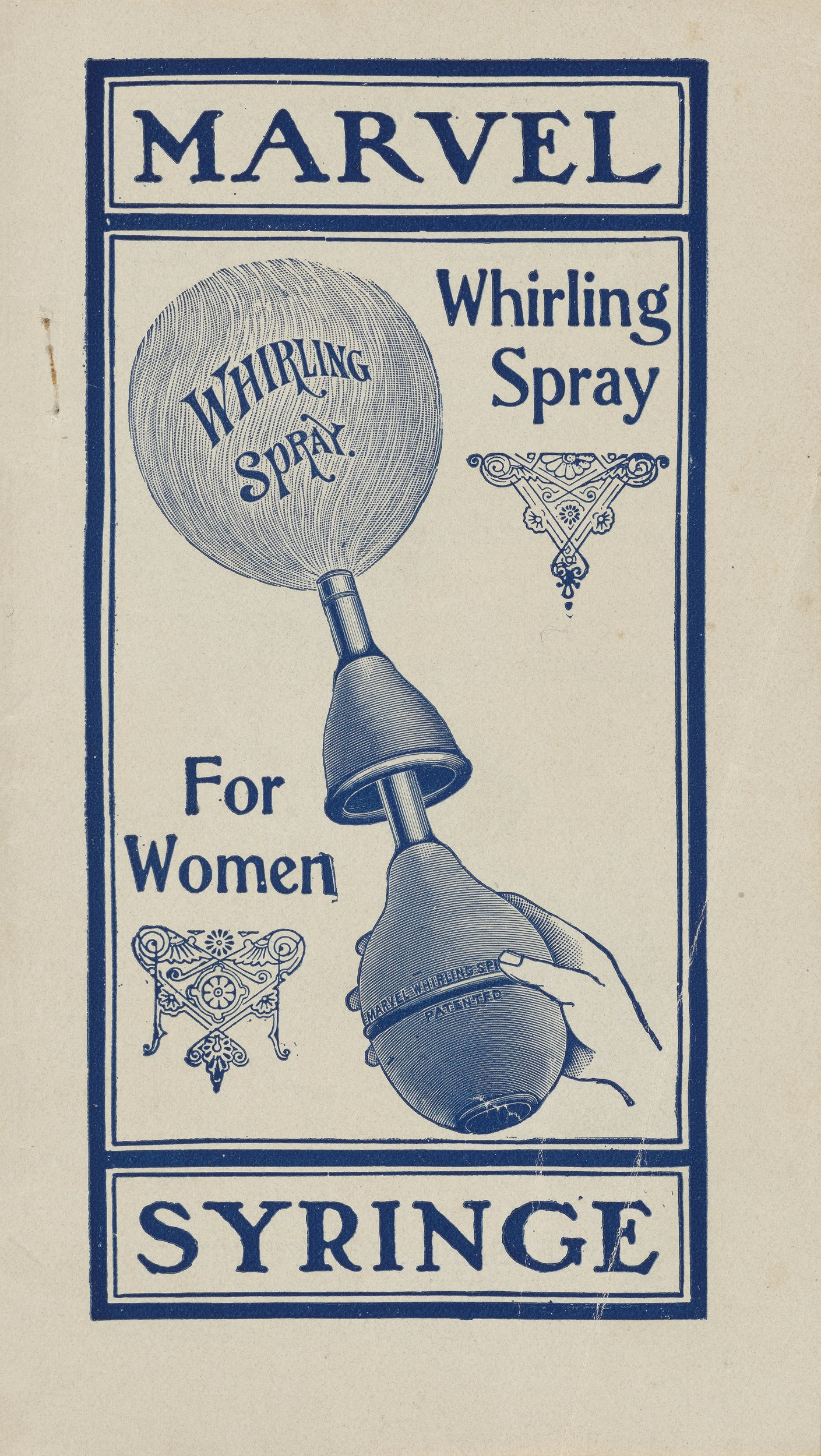

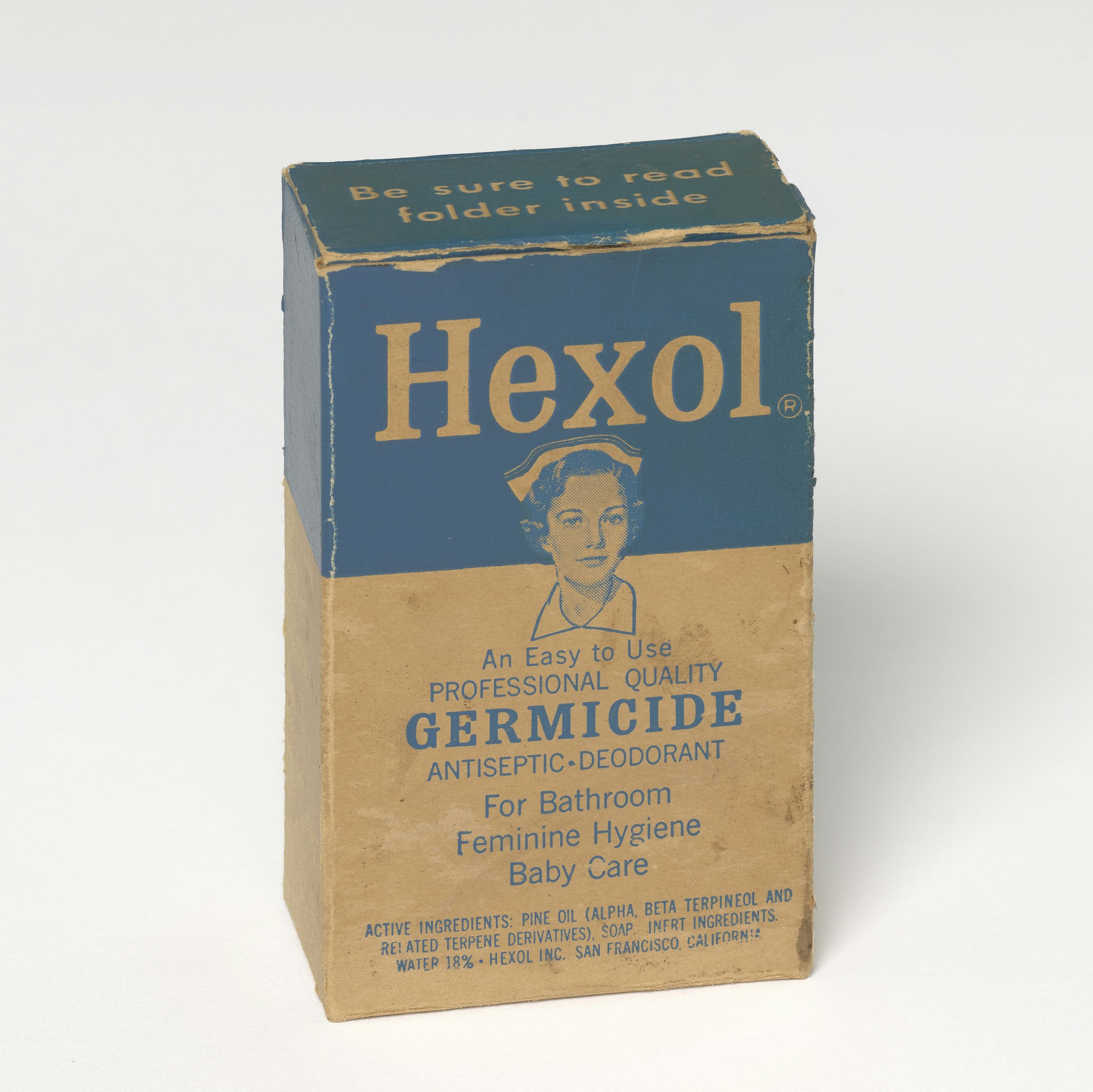

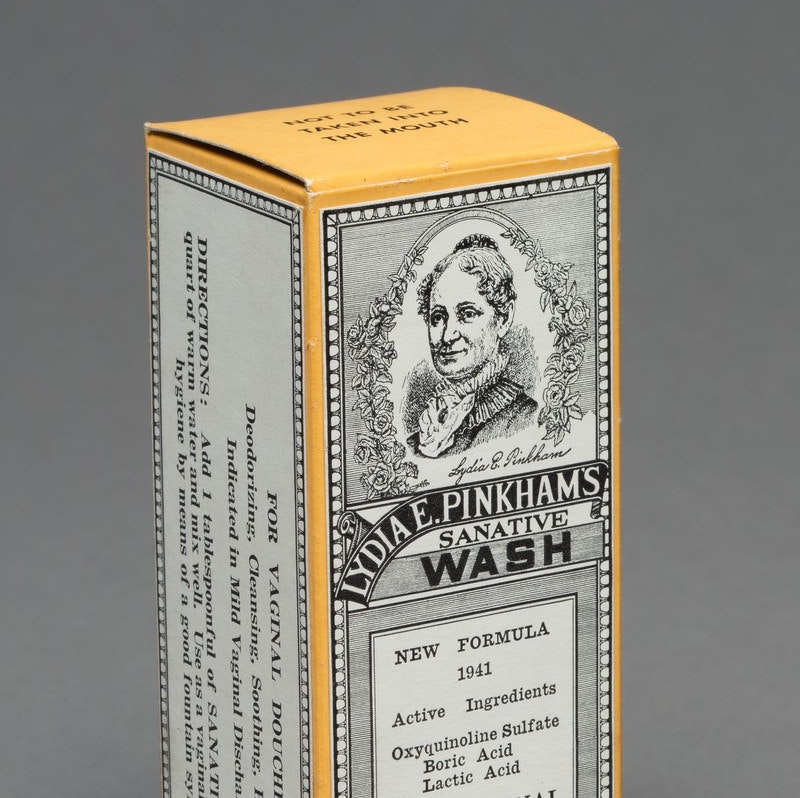

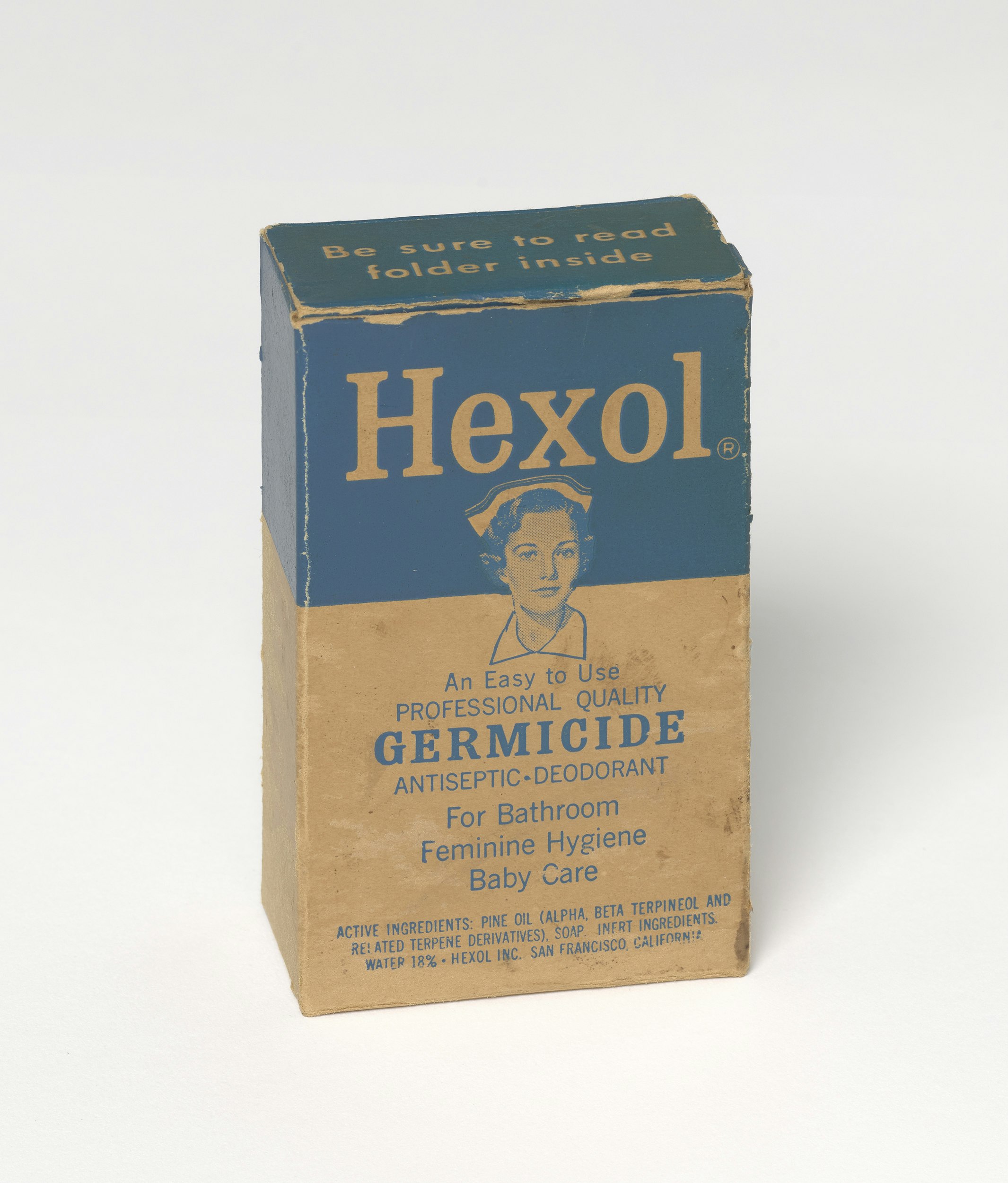

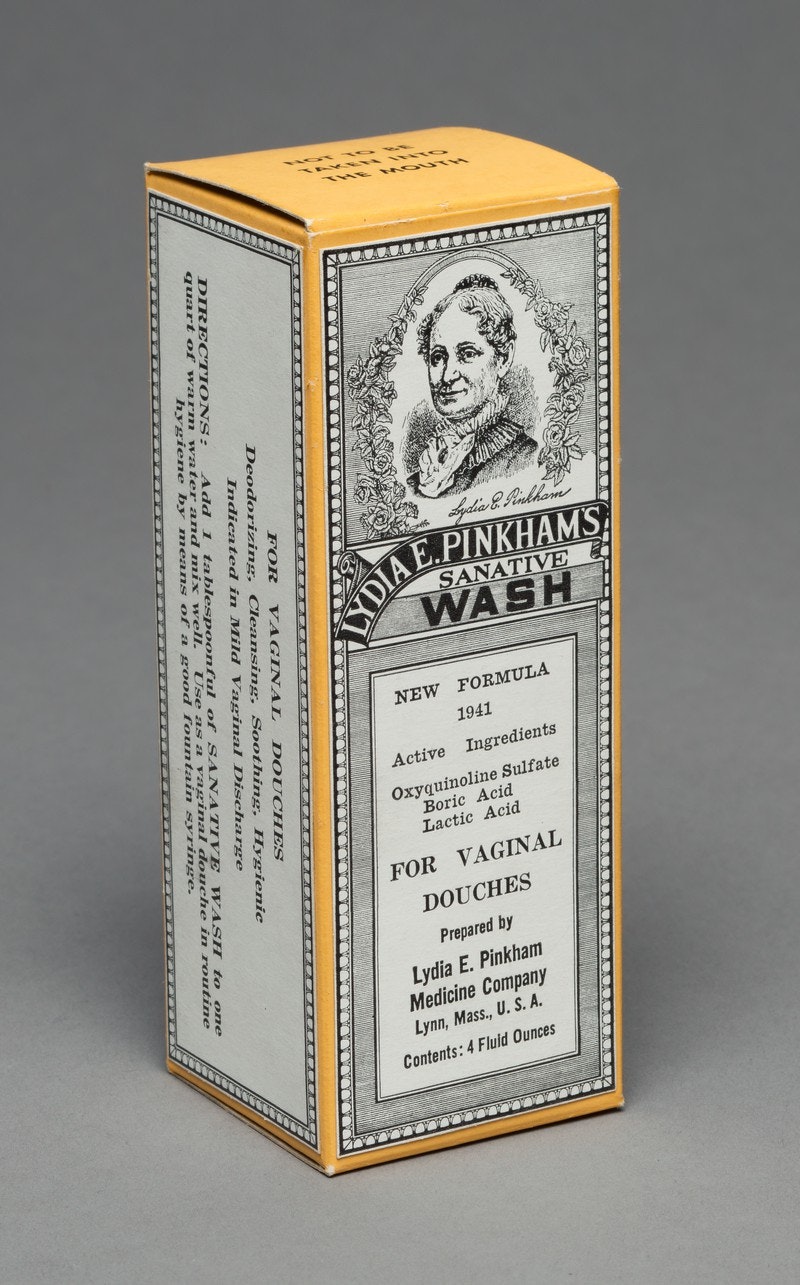

Feminine hygiene product advertising, frequently in the form of educational pamphlets, taught women’s anatomy through diagrams while offering advice on what one could and could not do while menstruating. Curative medications for various women’s complaints were marketed to fix the troublesome female body; antiseptics and douches promised to sanitize offensive vaginas. Pad and tampon brands advertised guarantees of no leakage, no odors, no possibility of being found out.

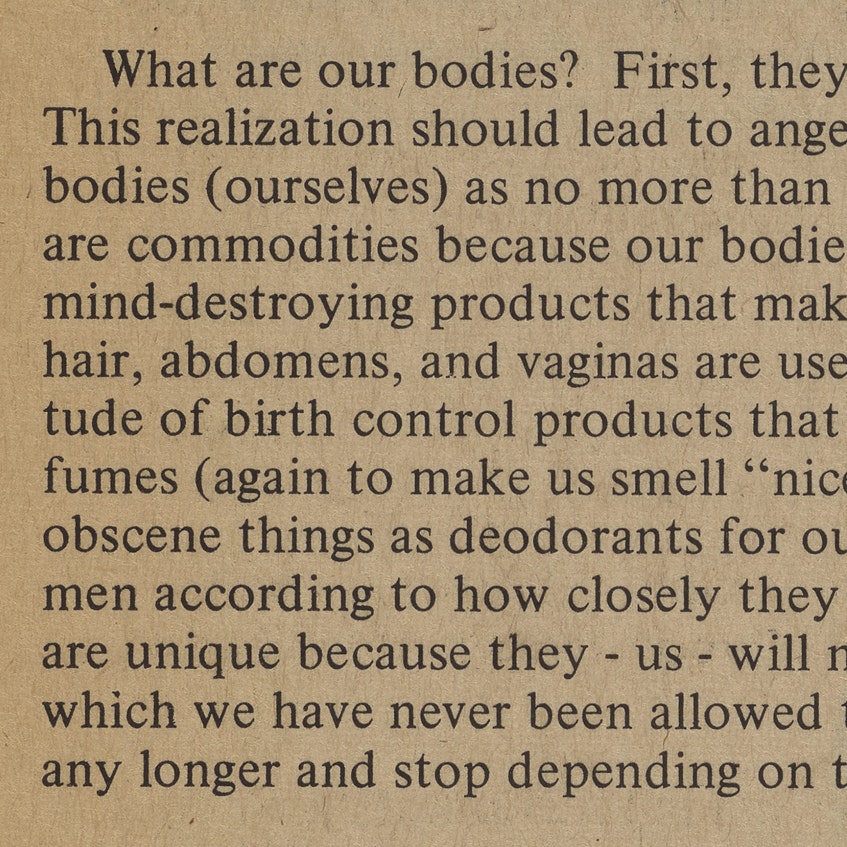

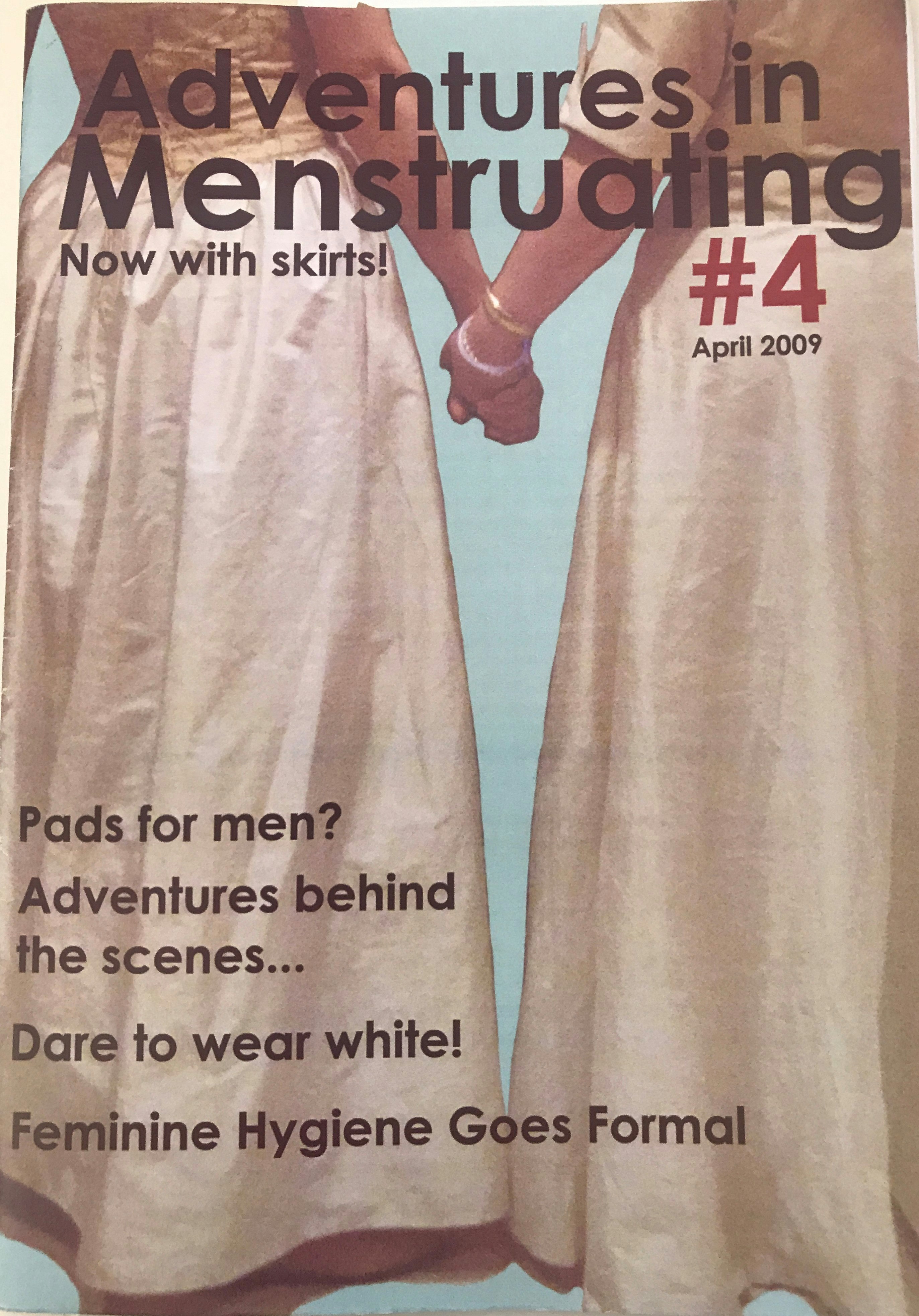

With the women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s, feminists responded to the incessant call for menstrual secrecy and cleanliness through transformative health publications, poetry, and artworks. The exhibition highlights the groundbreaking work of the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, the words of menstruating girls and women, and the production of zines that challenge toxic products and gendered assumptions.

Today, a worldwide movement for menstrual equity strives to end cultural stigma, to address period poverty, and to develop toxin-free, sustainable products. Menstrual equity activism centers class and race as well as gender. The movement fosters acceptance of all menstruating people.

Female Complaints & Patent Medicines

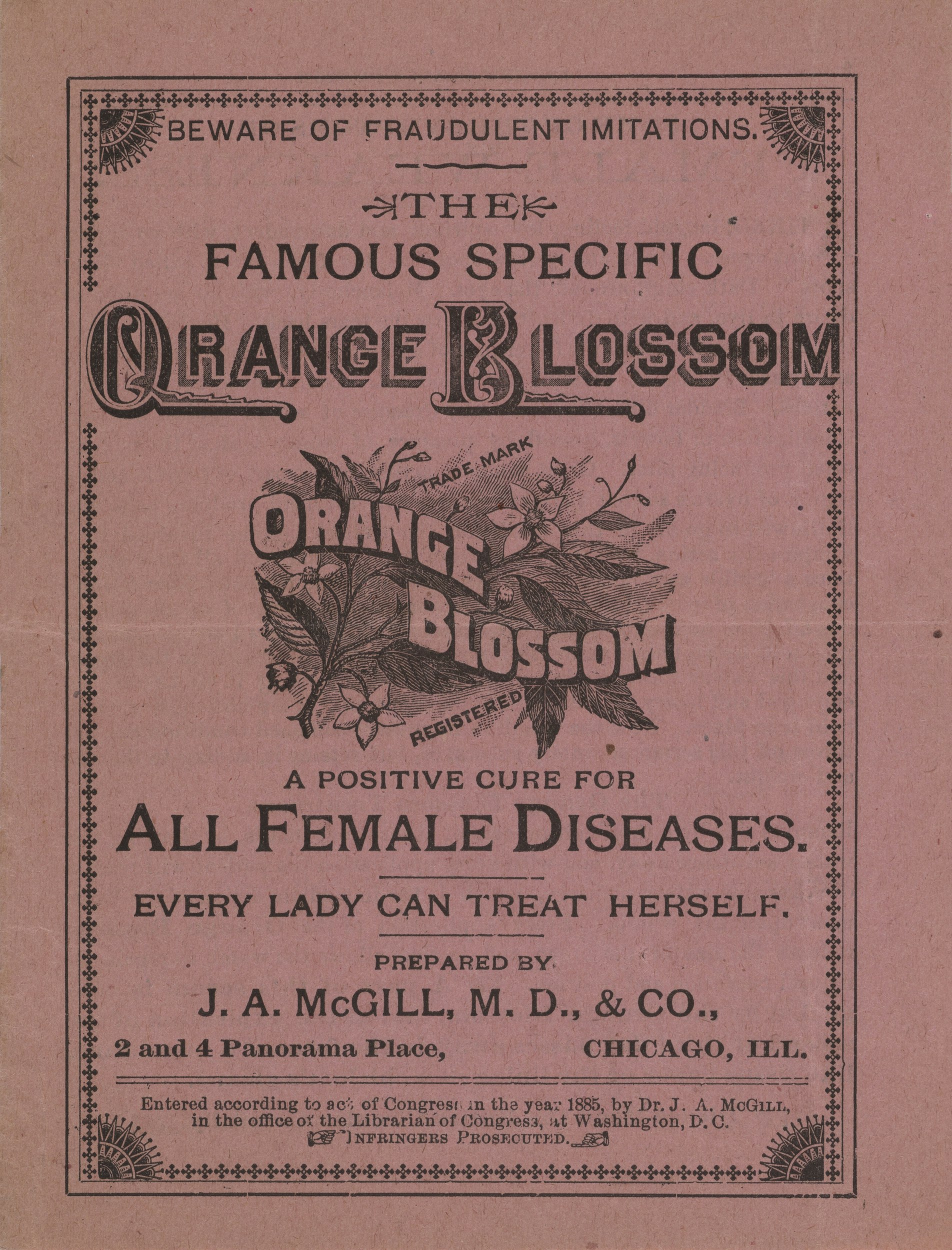

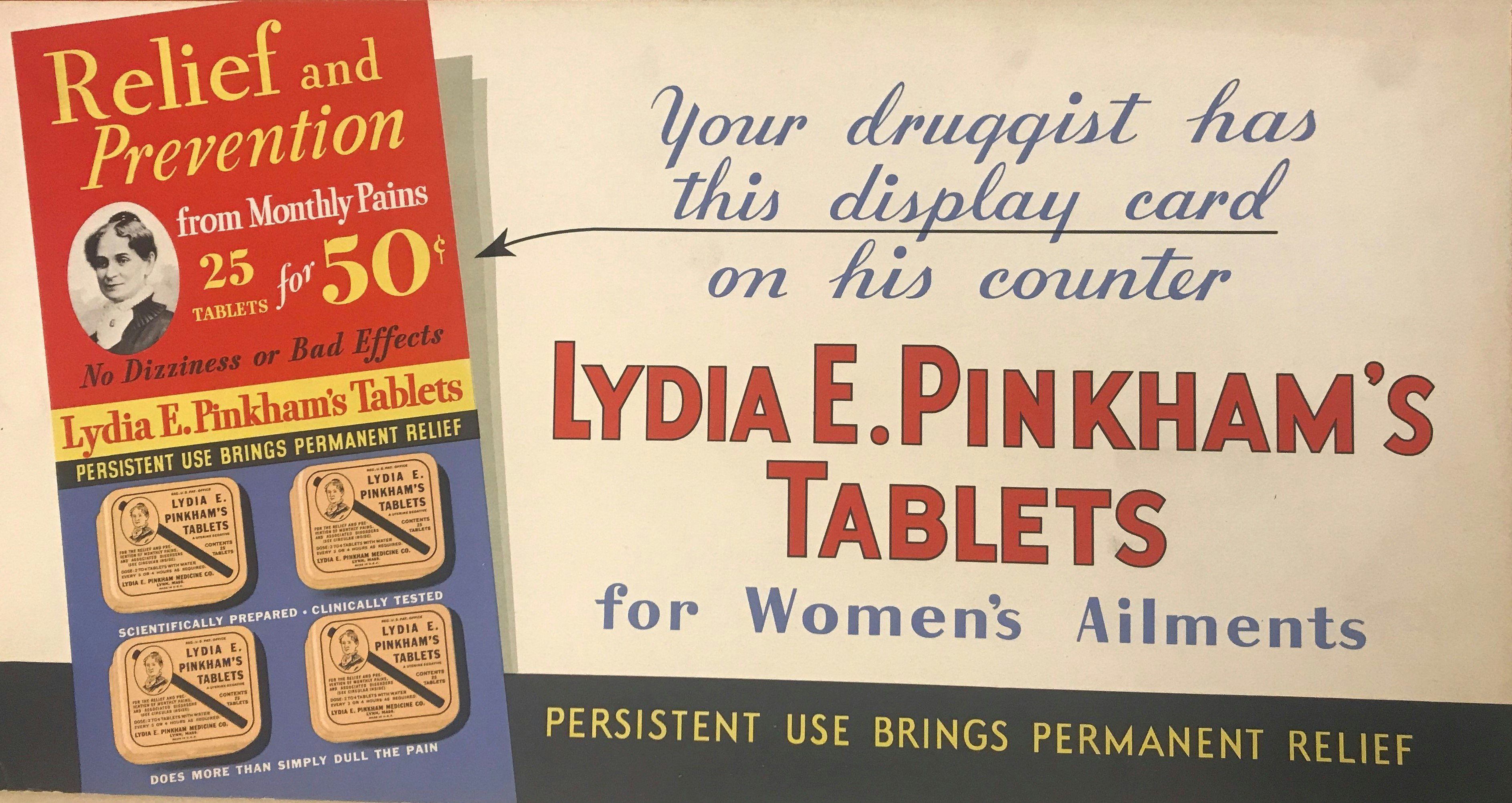

Menstruation has long been surrounded by misinformation, secrecy, and shame. Theories of inherent female weakness, the absence of convenient and reliable menstrual products, primitive sanitation, and poorly understood science combined to provide opportunities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries for purveyors of spurious treatments and cures for female ills.

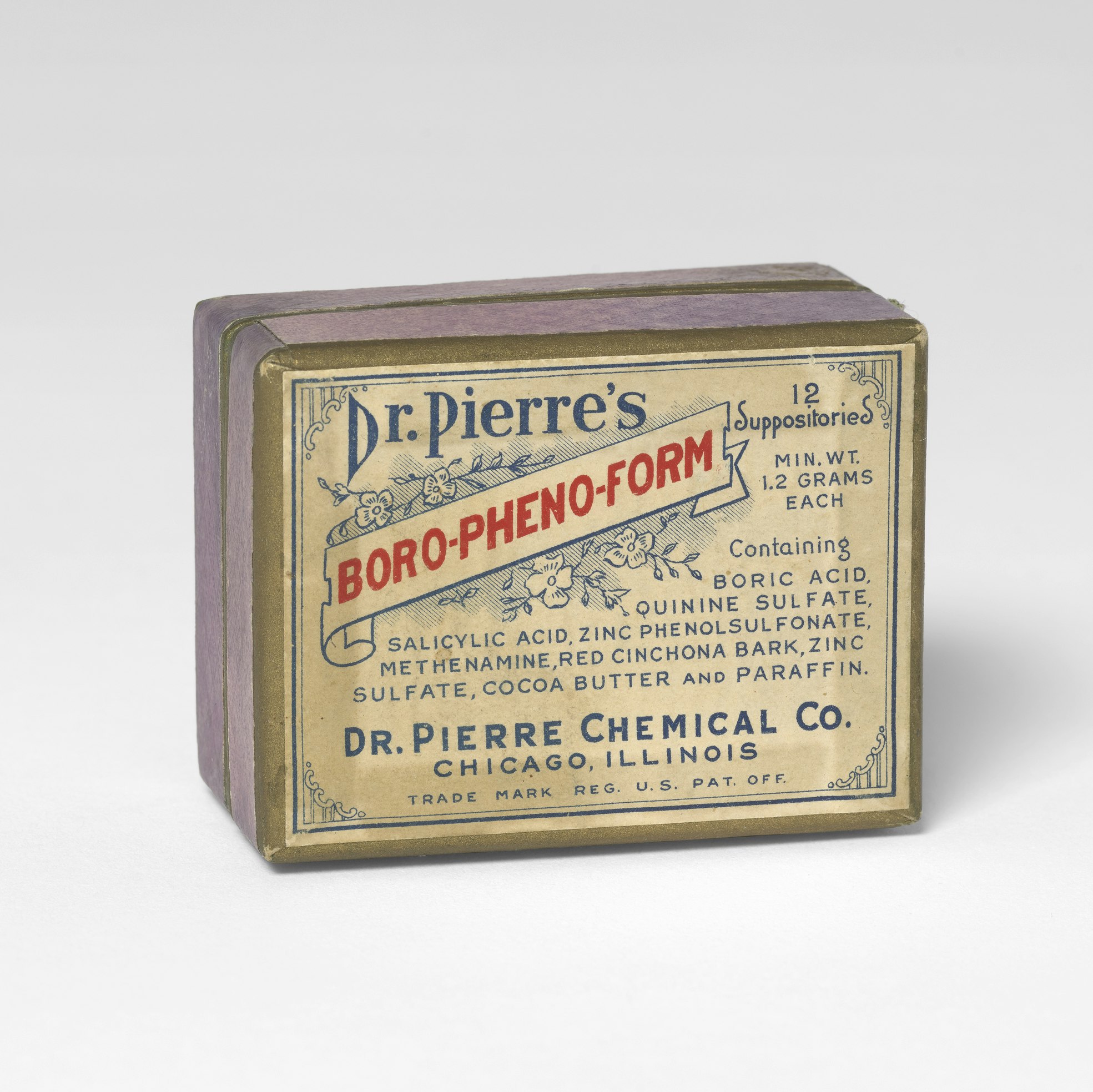

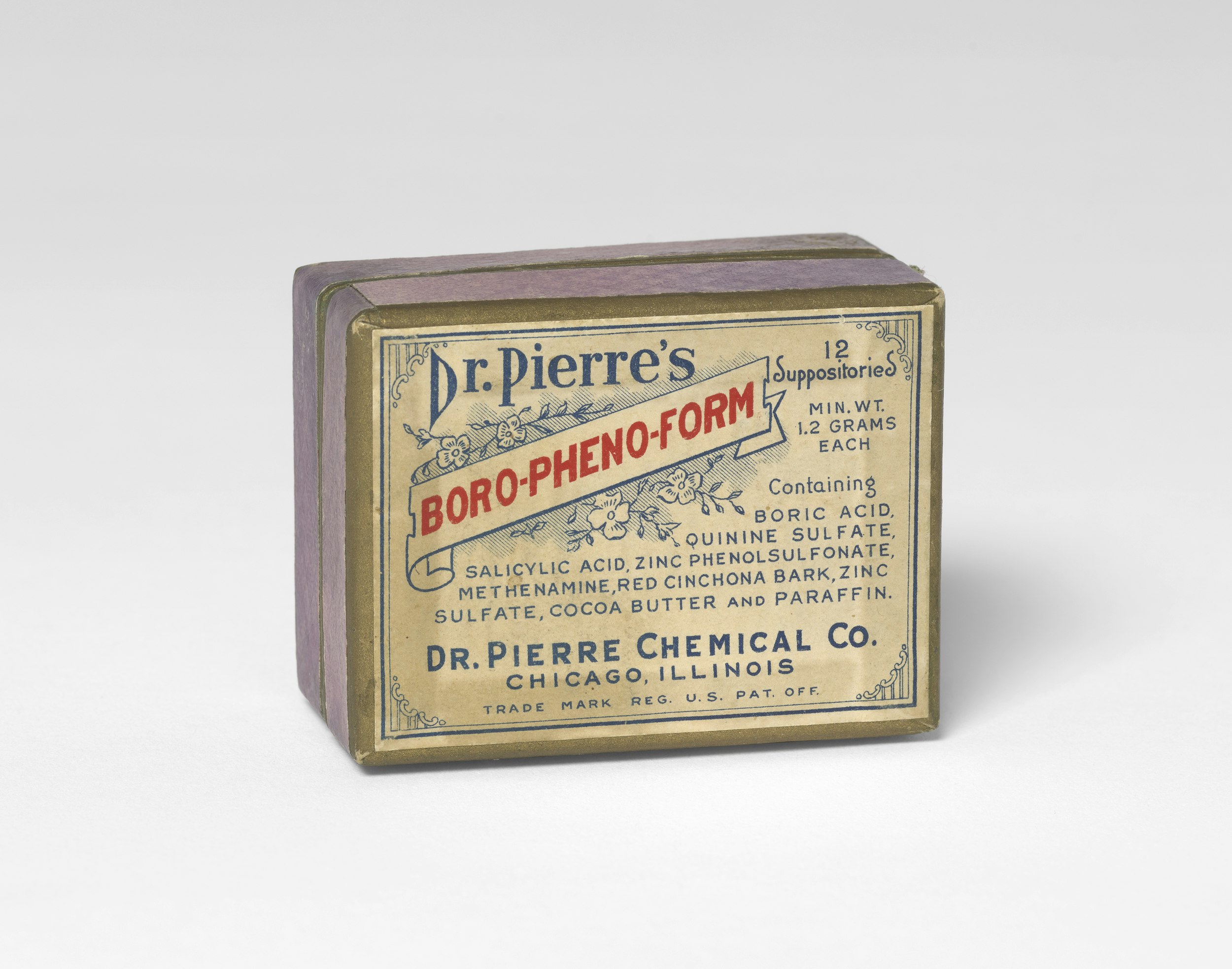

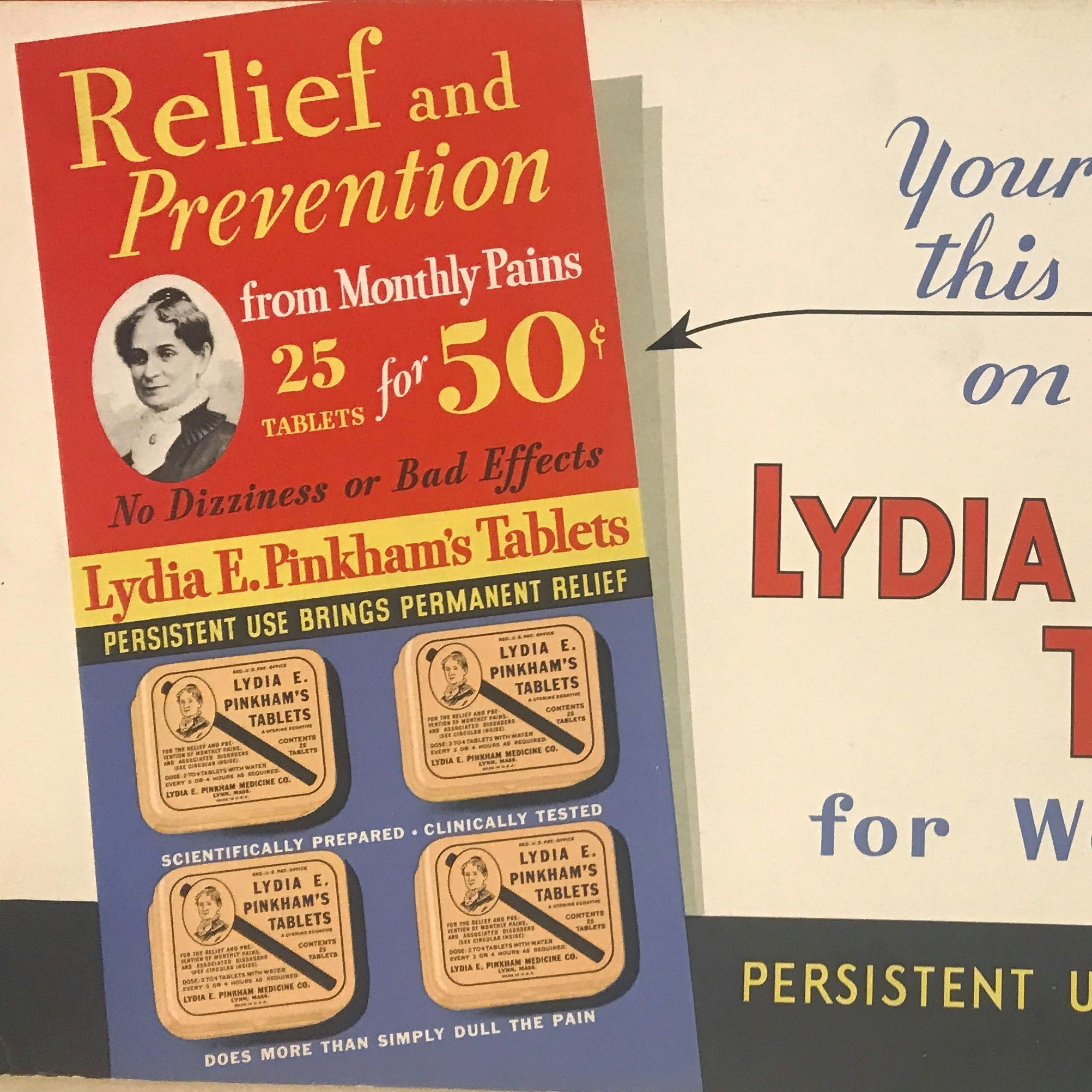

Brochures peddled elixirs combining herbs and alcohol to ease discomfort; disinfectants and douches to remove embarrassing odors and secretions; emmenagogues to ensure regularity and possibly also to function as abortifacients; and painkillers. Alongside were detailed medical explanations revealing the science of menstruation to women unaware of their own biology and too embarrassed to ask a doctor. By midcentury, pharmaceutical companies were promoting hormones, mood-stabilizing drugs, and diuretics to eliminate all monthly upsets. Though many products were ineffective, unsafe, or discredited by investigations, pamphlets replete with testimonials from doctors, nurses, and satisfied customers ensured brisk sales.

Ergot-Apiol is illustrative of a fraudulent cure for women’s “disorders” that was sold under several brand names. Ergot is a fungus that grows on rye; apiol is an extract from celery and parsley leaves. Both had been used since the Middle Ages to stop bleeding after childbirth and also to induce abortions. Both can be extremely toxic, causing liver and kidney damage and gangrene due to impaired blood circulation. This toxic “cure” was discredited and banned from production under the Food and Drugs Act in the 1933 case U.S. vs. 39 Tins of Premo Ergot-Apiol Capsules.

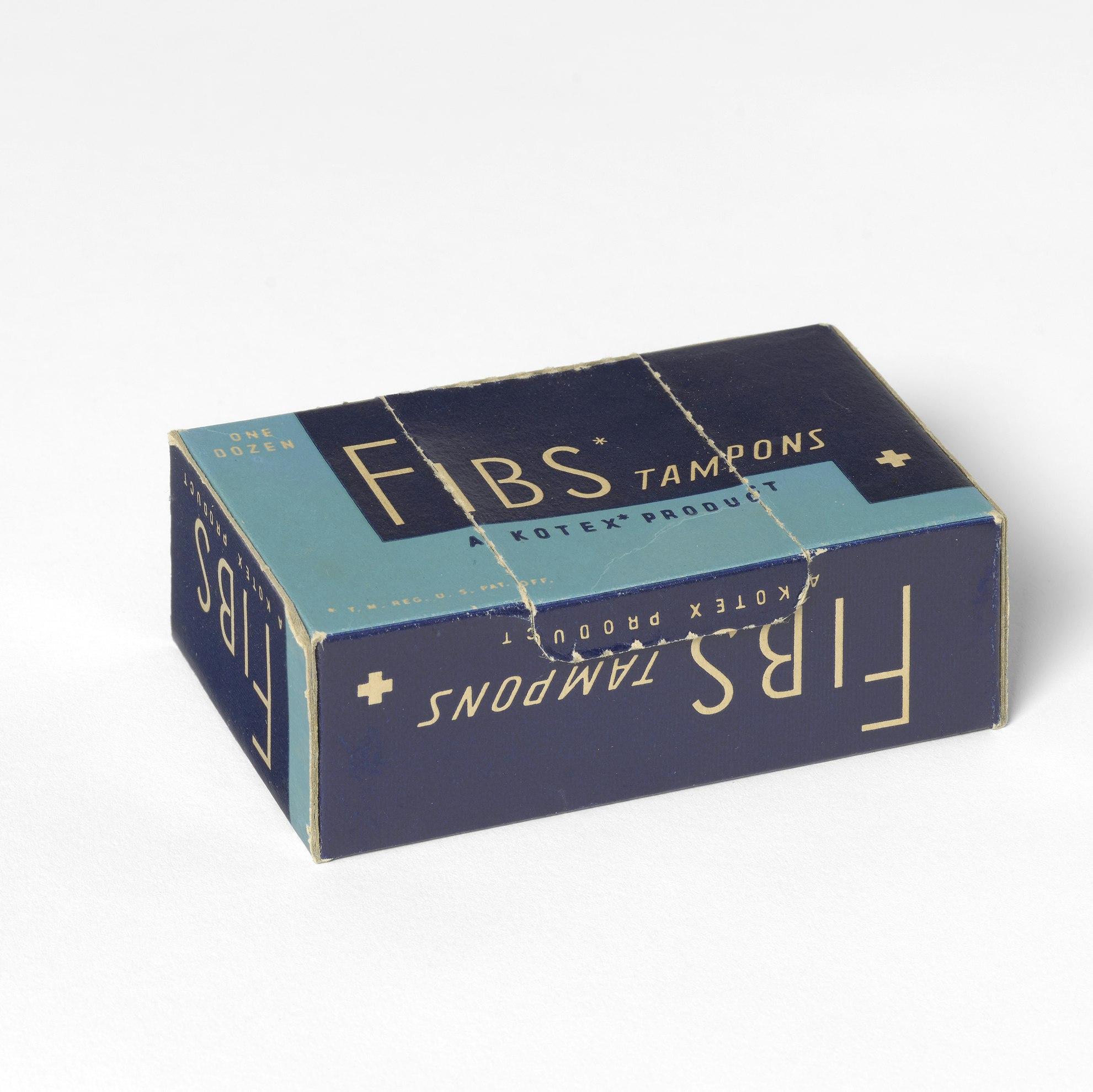

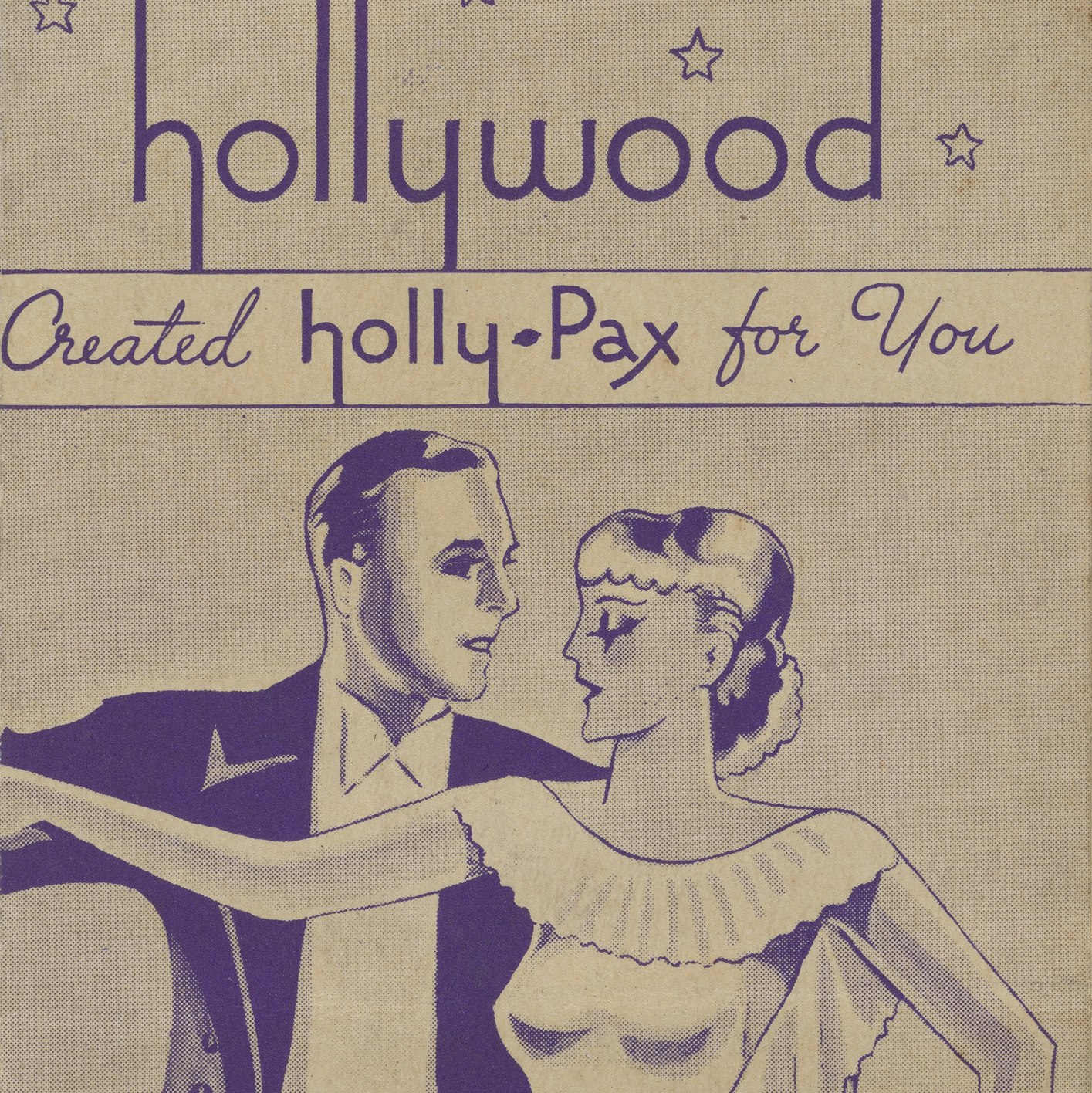

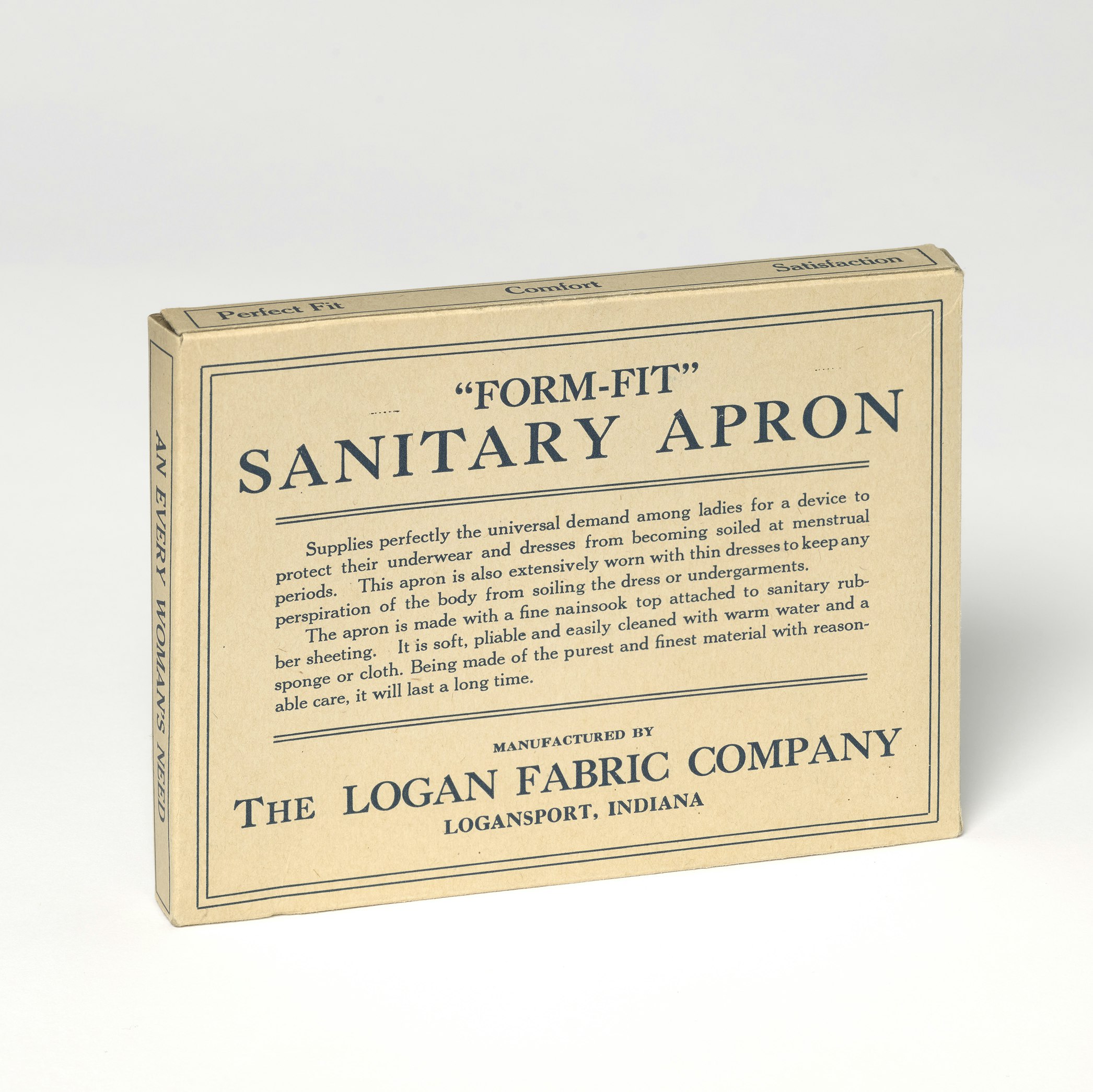

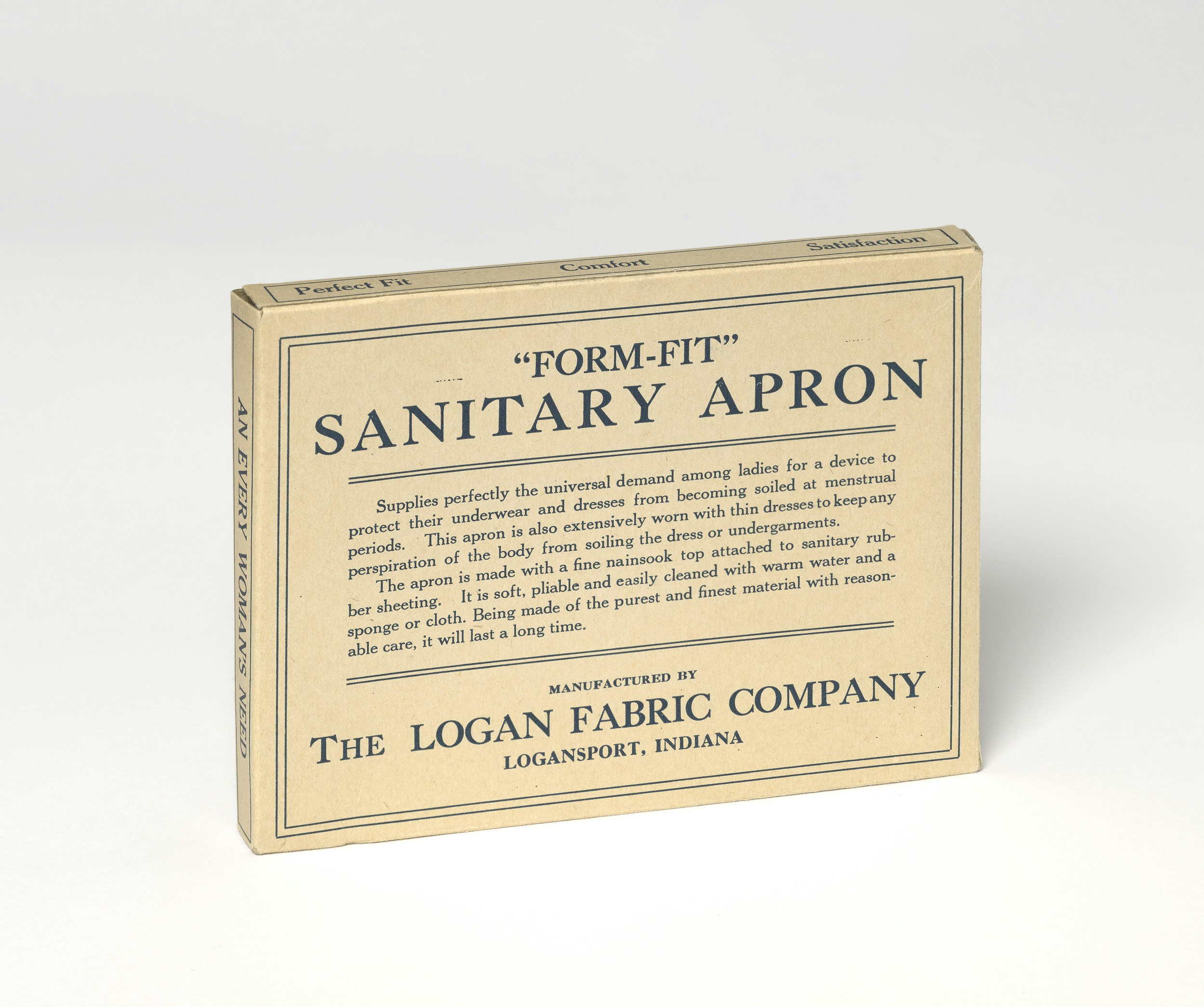

Feminine Hygiene Products

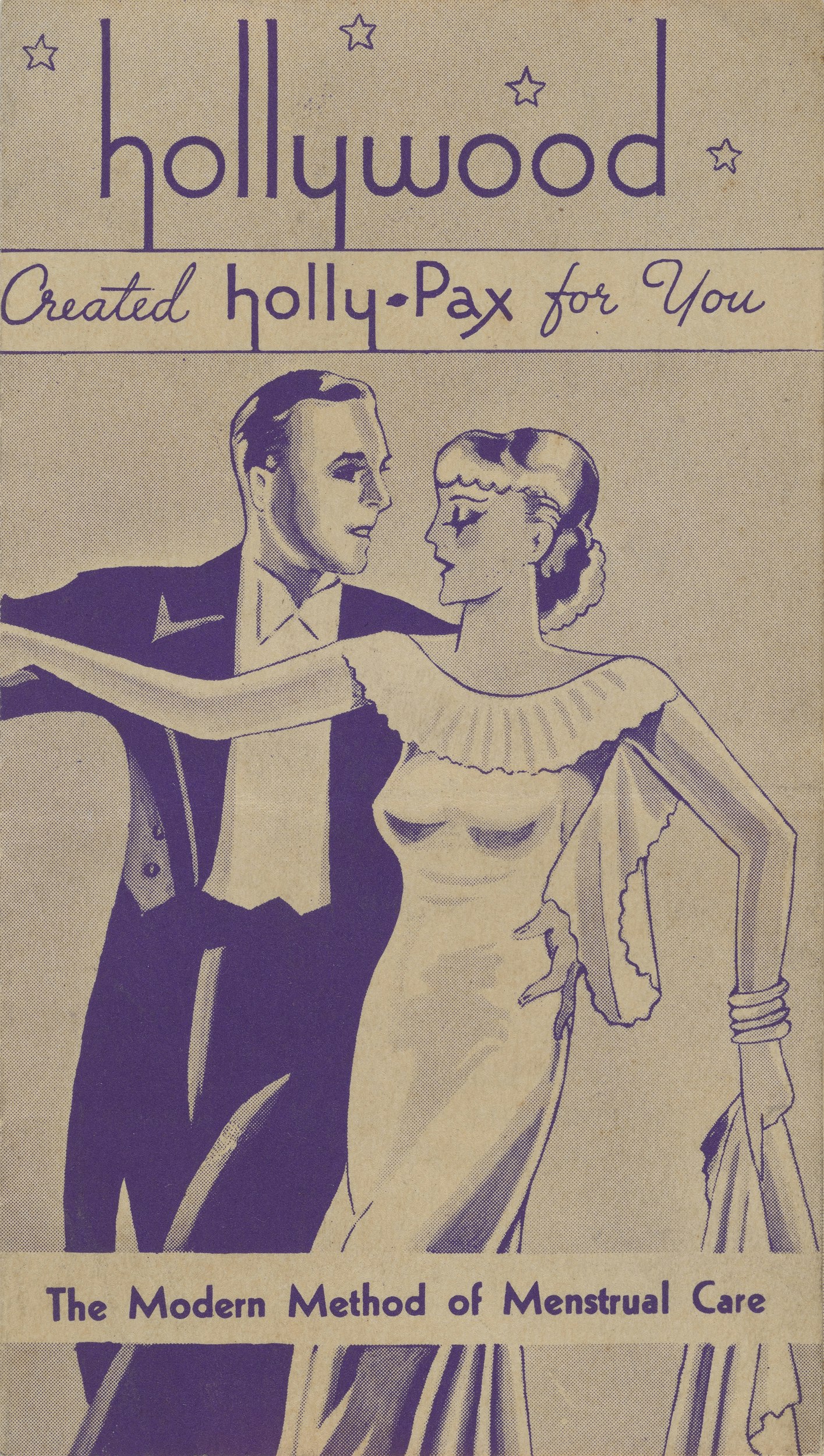

Devices for capturing menstrual flow began to replace cotton batting and rags in the late 19th century. During World War I, cellucotton, a paper biproduct used to make bandages, was repurposed by nurses for use during their periods. Companies manufacturing and promoting disposable cellucotton pads and tampons sprang up in the 1920s and 1930s, and the first menstrual cup appeared in the 1930s. As time progressed, more products were developed, including one that claimed to have been invented in response to Hollywood’s need for actresses to be available for filming at all times. The production and sale of feminine hygiene goods became an increasingly lucrative business, and in 1927, Modess commissioned Lillian Gilbreth to undertake the first scientific study of the use and marketing of these products.

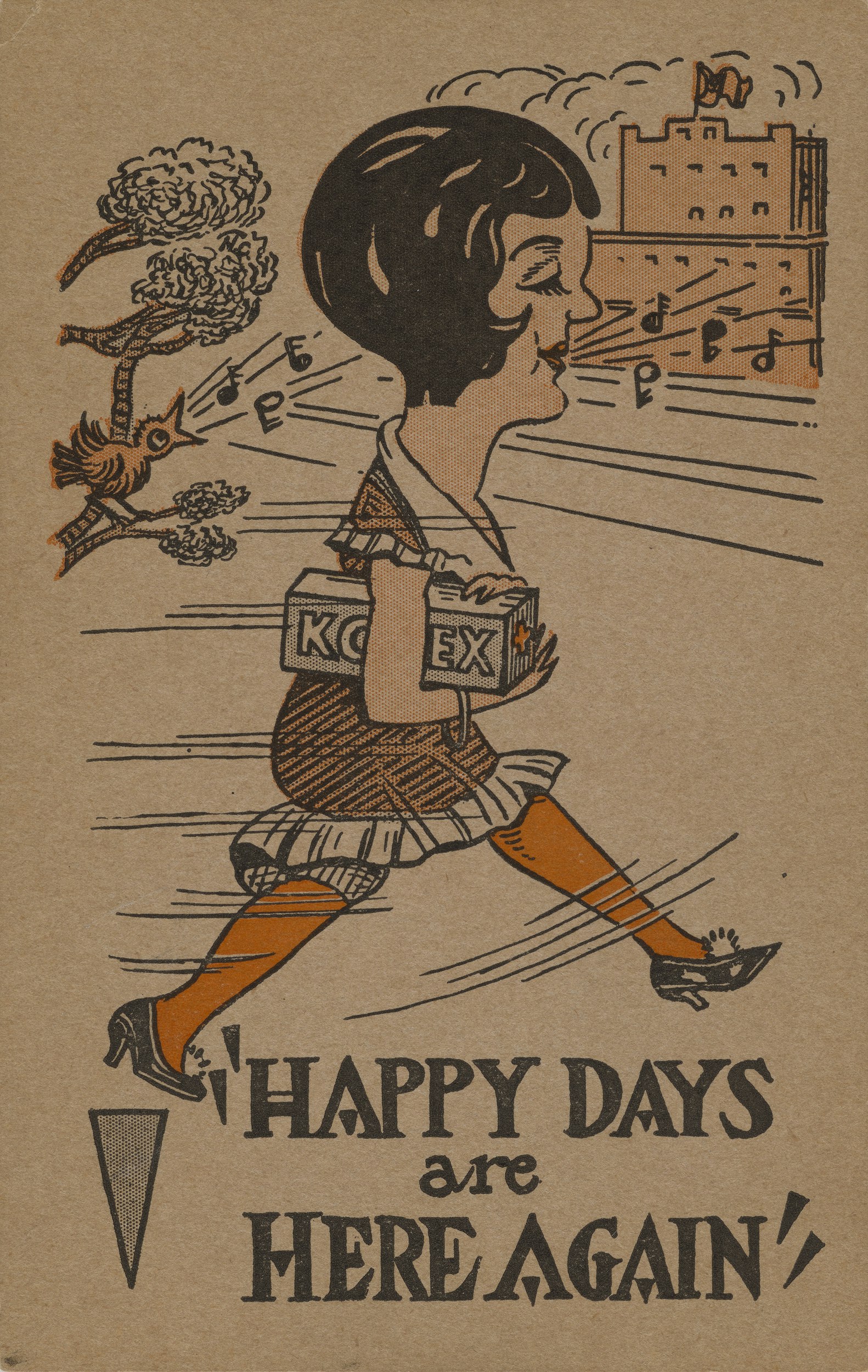

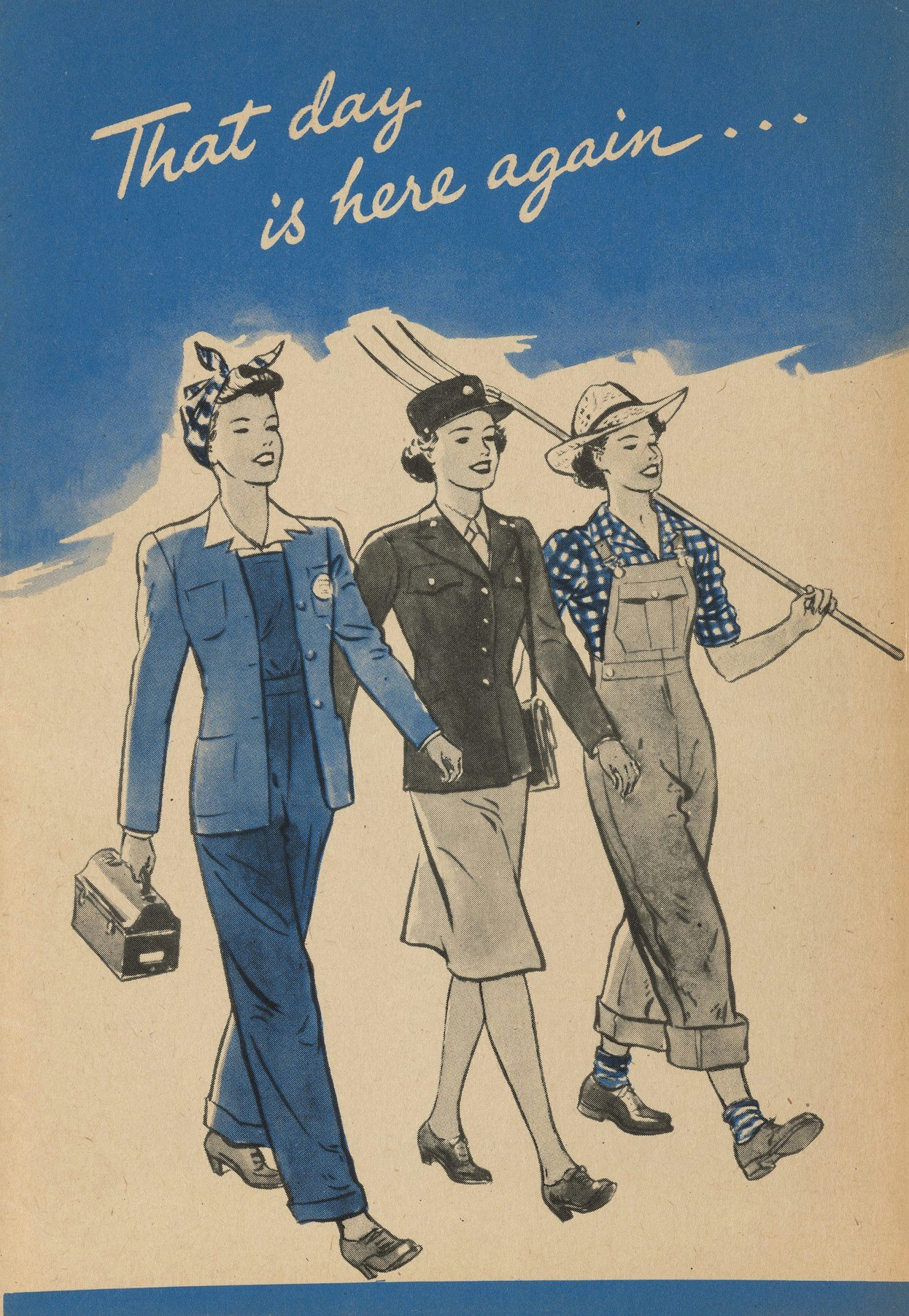

Advertising overcame taboos and took off in women’s magazines, promotional booklets, and, eventually, short films. Companies developed innocuous packaging and began placing their goods on store shelves to eliminate the need to ask for them. Ads emphasized the product’s invisibility and the freedom they gave wearers to pursue most activities even while menstruating. By the time World War II began, women were depicted working dependably and uncomplainingly in factories and offices during their periods.

Medicine Cabinet

Over the course of the 20th century, dubious and sometimes harmful concoctions for female ailments were replaced by mainstream medical solutions along with safer homeopathic treatments. Menstrual pads and tampons evolved and some are now made from organic, biodegradable cotton with no chemicals or synthetic materials. Menstrual underwear and cups have become readily available alternatives that can be washed and reused.

The symptoms of premenstrual tension were widely discussed in the 1980s as premenstrual syndrome (PMS), both a medical and a social problem. Symptoms attributed to PMS include moodiness—short temper and irritability—odd food cravings, depression, inability to focus, and general malaise. PMS lives in disputed territory between a natural physiological process and a psychiatric disorder. Cultural tropes often resemble the old notion of female hysteria and manifest as insults or jokes. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) entered the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, in 2013 (DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association).

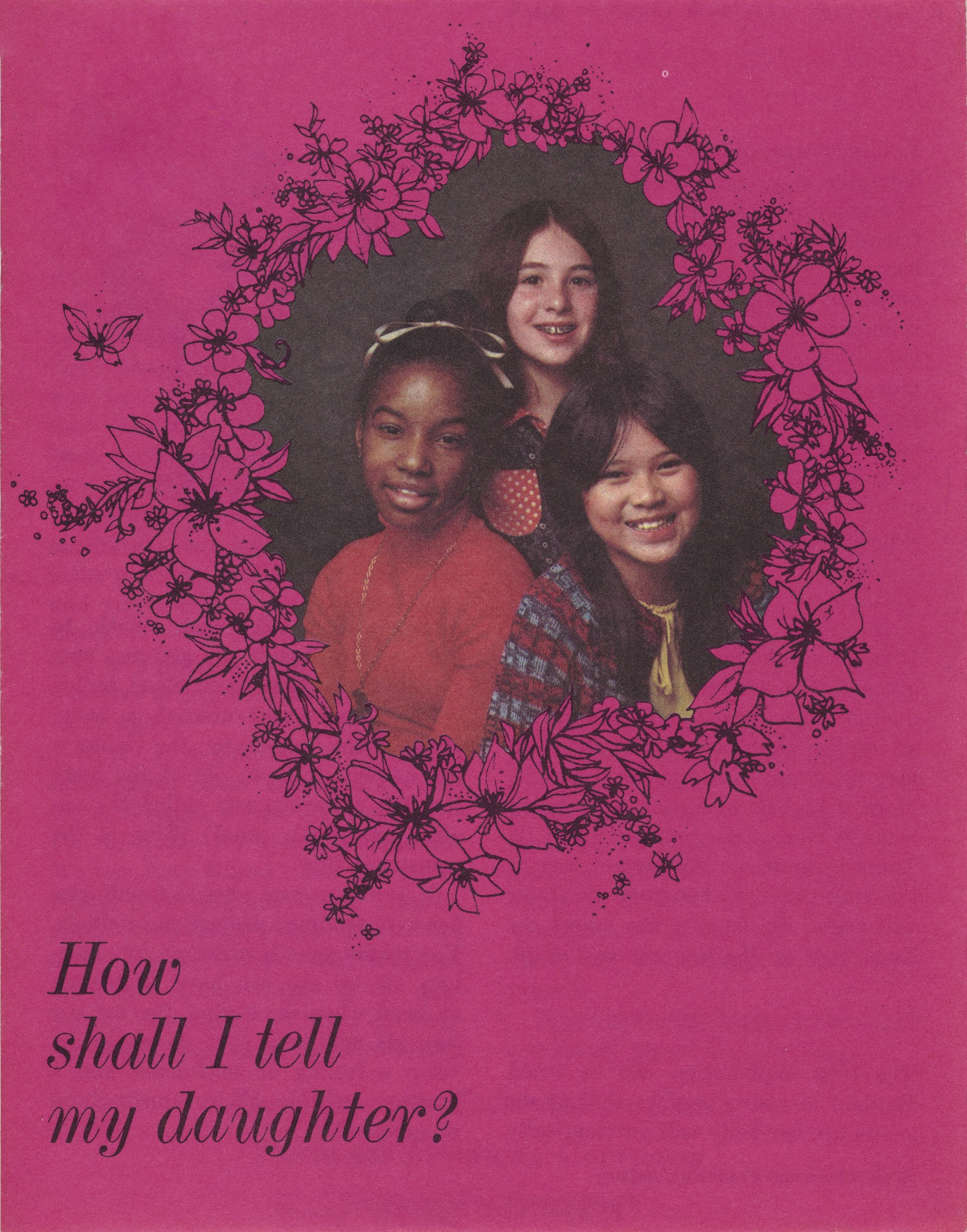

Educating Girls

From the 1930s on, companies produced booklets for girls and their mothers that explained menstruation and promoted their products, positioning themselves authorities on matters of feminine hygiene. Their underlying assumption was that women were likely to stick for the duration of their menstrual life with whichever sanitary product they had used as girls. Some booklets spoke directly to mothers, telling them how to prepare their daughters; others were designed to be read by the girls themselves, or to be used in school settings where a companion film might be shown. Modess, Kotex, Carefree, and other brands regularly updated their messaging about approved activities during periods and the use of tampons by virgins, reflecting changes in American societal norms. The pamphlets displayed here reveal an evolution as, from the 1960s on, illustrations included girls of diverse backgrounds, and booklets were published in Spanish. Warnings about the threat of toxic shock syndrome were added to the booklets in the 1980s.

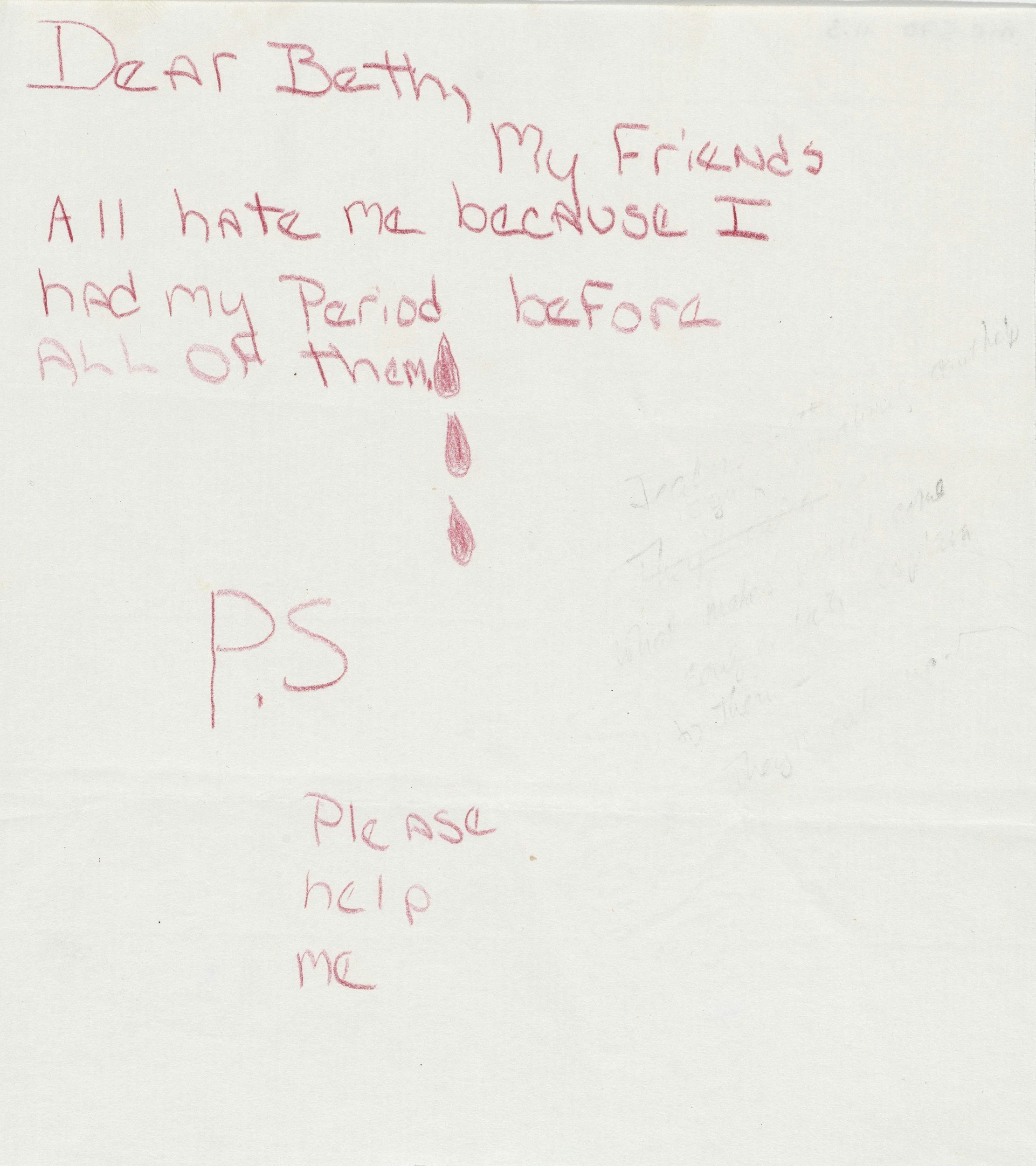

Voices of Girls & Boys

The anxiety and curiosity of young girls and boys is felt in their urgent requests for information from “Ask Beth,” an advice column created by Elizabeth C. Winship for The Boston Globe in 1963 and syndicated across the country from the 1970s through the early 2000s.

The diary of a 12-year-old girl living in Brooklyn, New York, in 1959 records the tactile presence and emotional impact of menstruation in a young girl’s life. Menstruation is hidden from view but is lived intimately.

Advertisements

The earliest disposable pad, produced by Johnson & Johnson in the 1890s, failed, largely because of the taboo on advertising menstrual products. Beginning in 1921, after considerable debate on editorial boards, magazines tentatively began to feature ads. A signal moment was the use of an Edward Steichen photograph of the model/writer Lee Miller in an evening gown in a 1928 magazine ad for Kotex—the first instance of a recognizable model being used for menstrual products.

Over the years, the visibility and breadth of advertisements for feminine hygiene grew. Beyond products specifically for menstruation, goods such as deodorizing powders and sprays were marketed to “fix” perceived feminine issues. While ads increased in prominence, many of them continued to reinforce norms of menstrual secrecy and stigmatization, such as by highlighting how the products could be purchased inconspicuously. Ultimately, ads sought to emphasize the discreetness, reliability, and comfort of their products while manufacturing a vision of femininity, freedom, and modernity for the wearer.

The Feminist Response

The 1970s women’s movement embraced menstrual cycles in new ways, changing the narrative from one of secrecy and primarily a hygiene problem to affirmation of a healthy, natural process to be openly discussed and experienced with pride as unique and powerful. Yet social and cultural expectations are often contradictory: Second-wave feminists in the fight for job and pay equity tended to minimize female physical differences, while later feminists of the 1990s were not reticent to discuss all aspects of menstruation not as diminishment but as reality. Today, girls in some cultures experience taboos that discourage school attendance during menstruation; people may be unable to afford period products; and access to products can be severely restricted for those experiencing homelessness or incarceration. Contemporary feminist publications such as zines highlight cultural acceptance of menstruation as inclusive of all genders: Not all women menstruate, and not all menstruators are women.

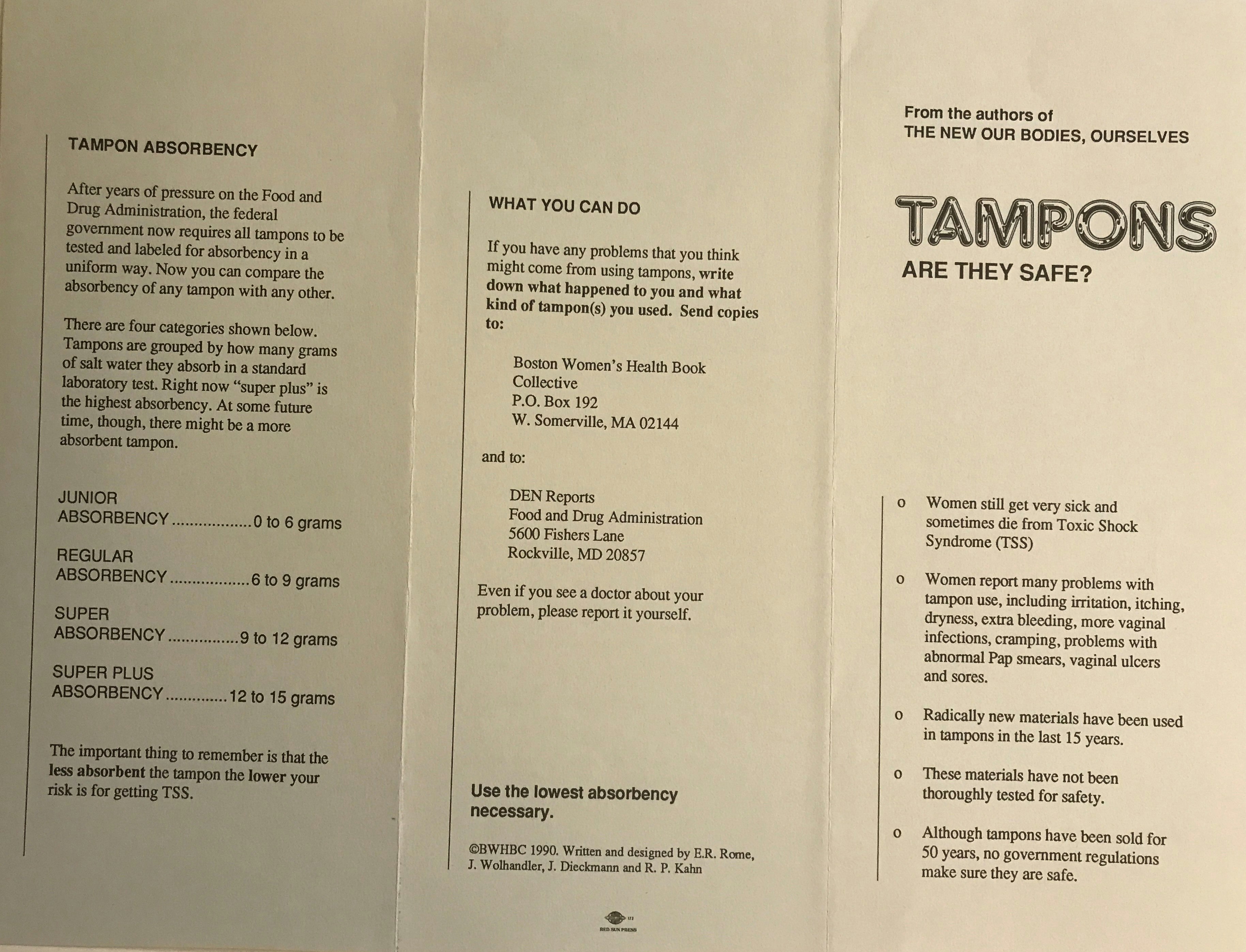

Leading the woman-centered health care movement of the 1970s, The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective produced a course book in 1970 that would become the groundbreaking book Our Bodies, Ourselves, now in its ninth edition and published in languages worldwide.

Feminist poets interrogated the personal experience of menstruation, deepening the public discourse. Judy Chicago’s art depicted menstruation as undeniably real.

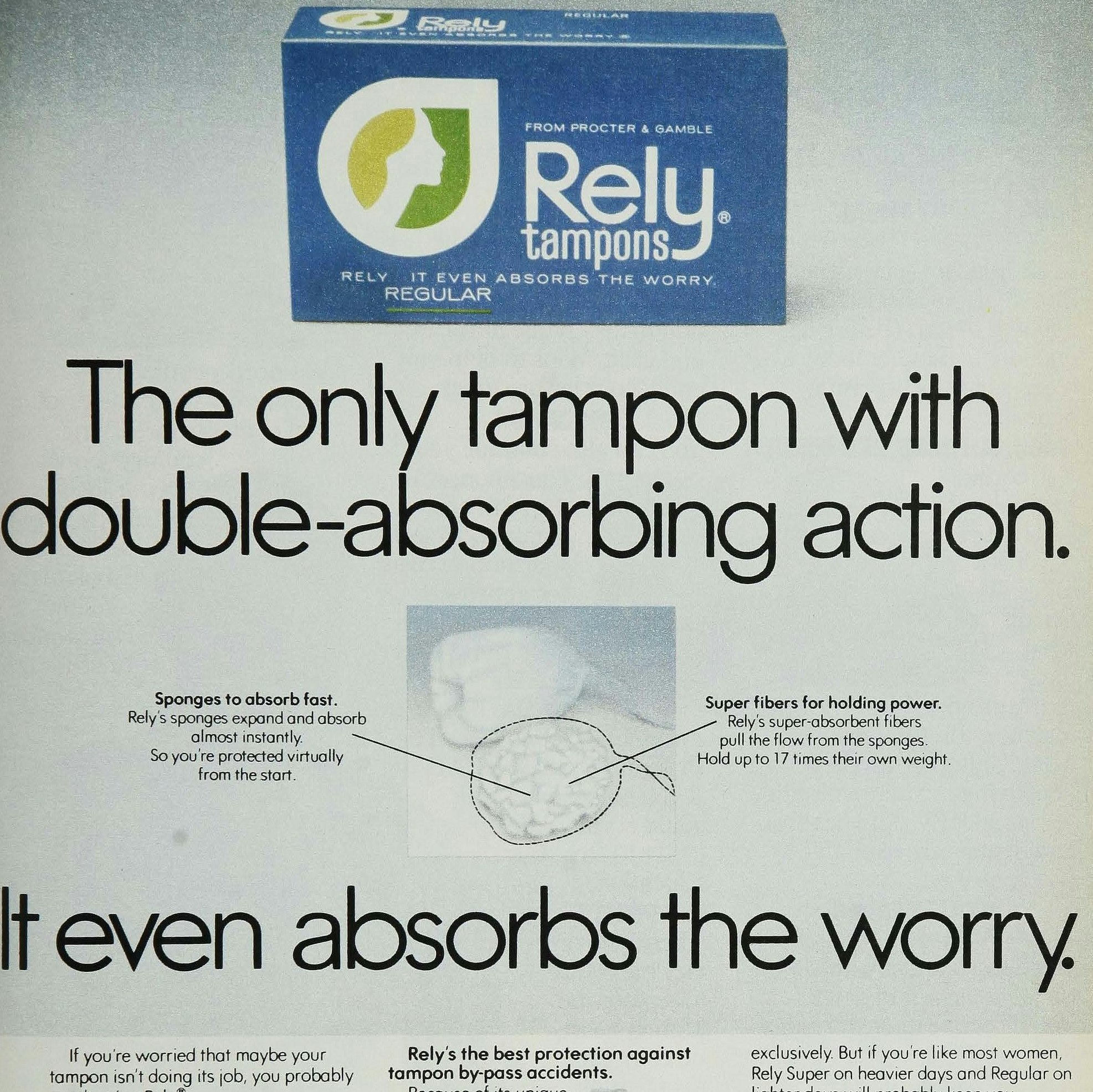

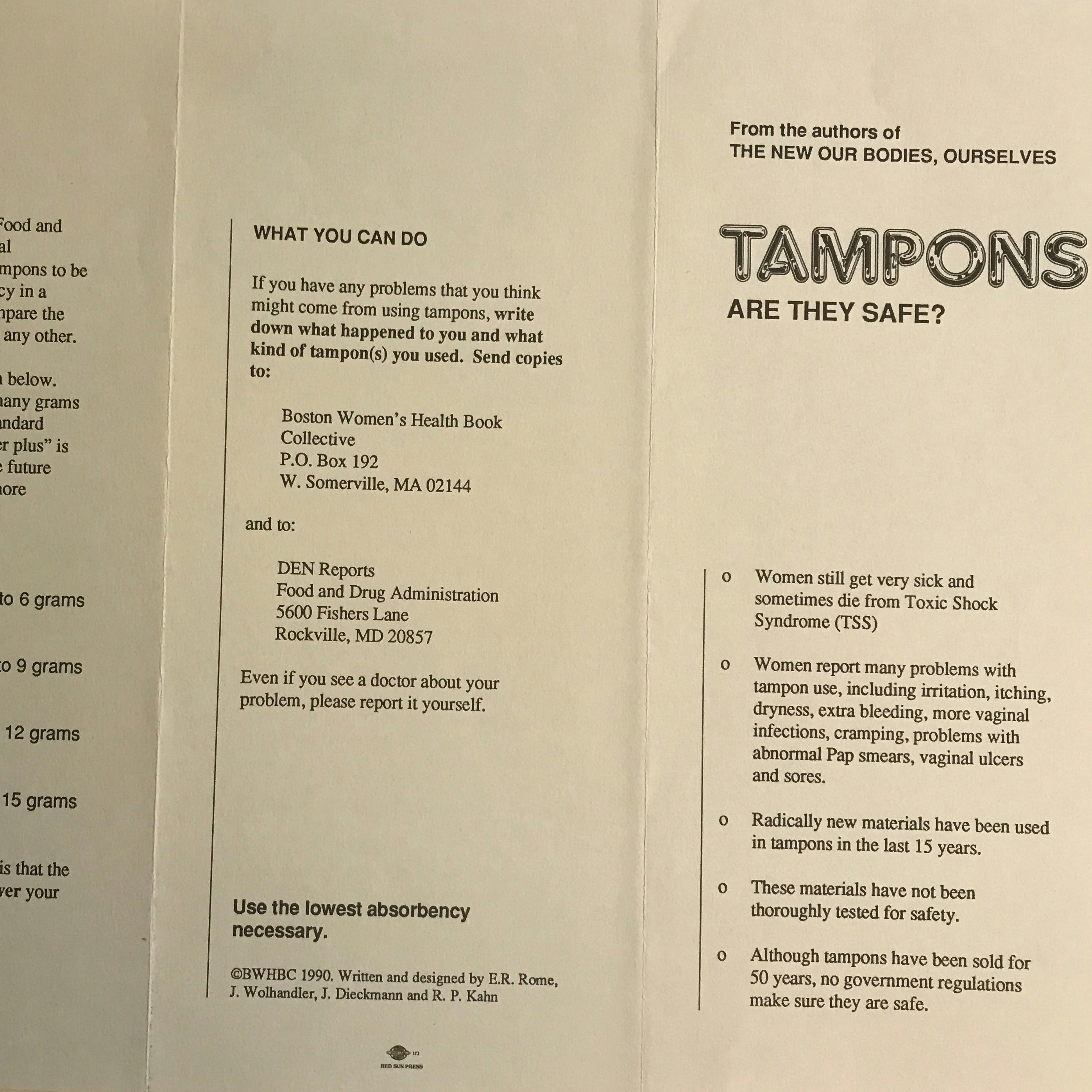

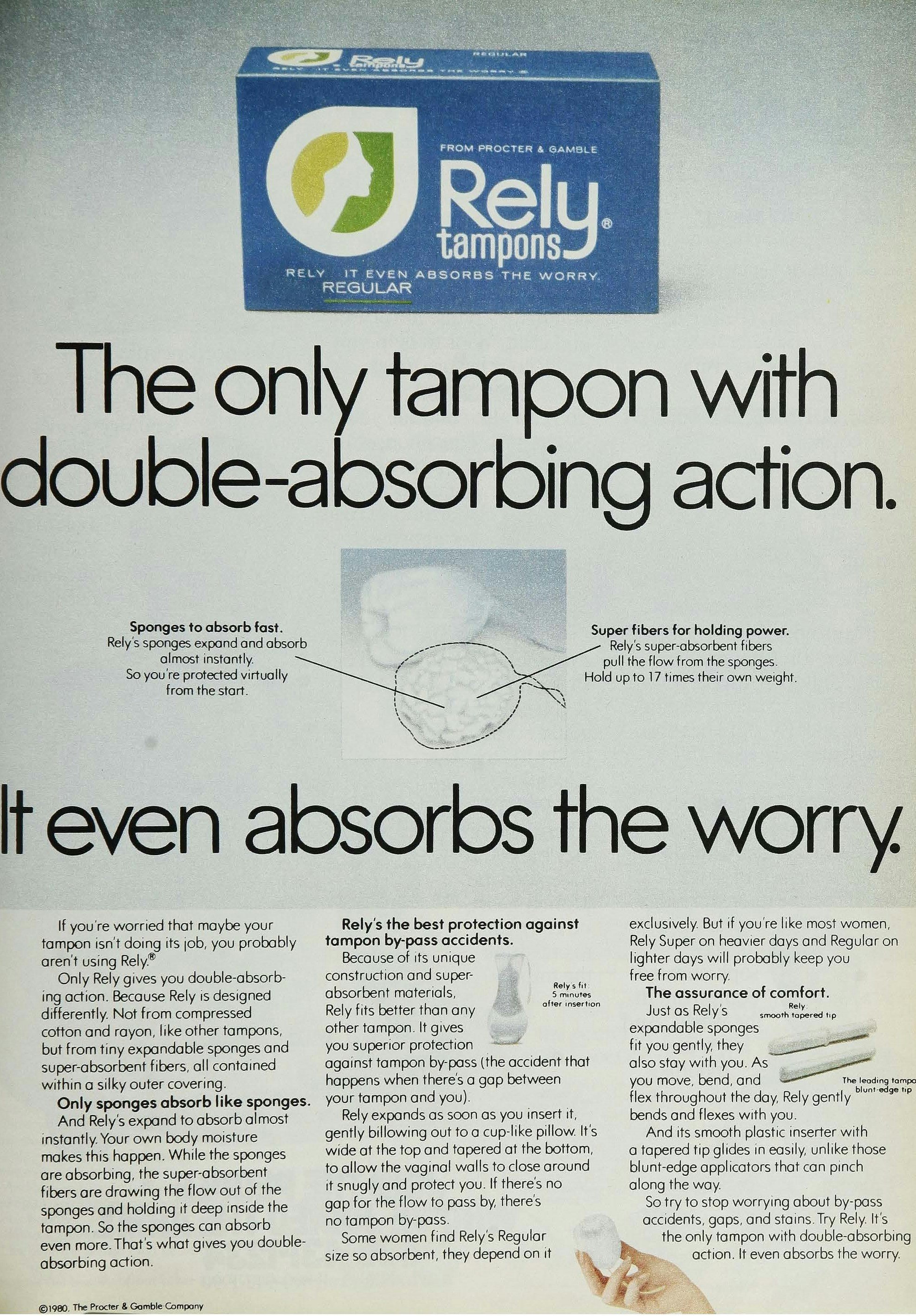

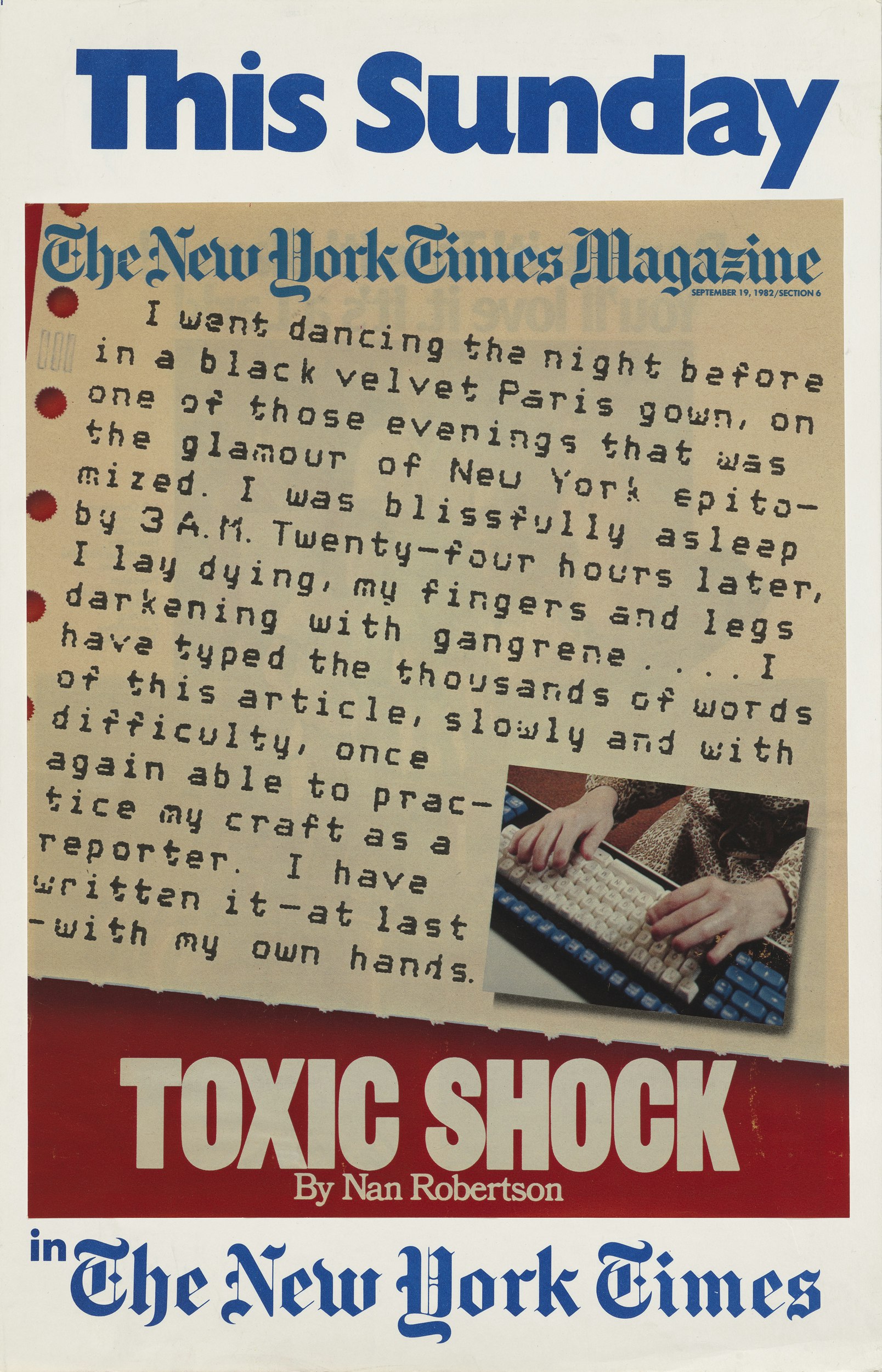

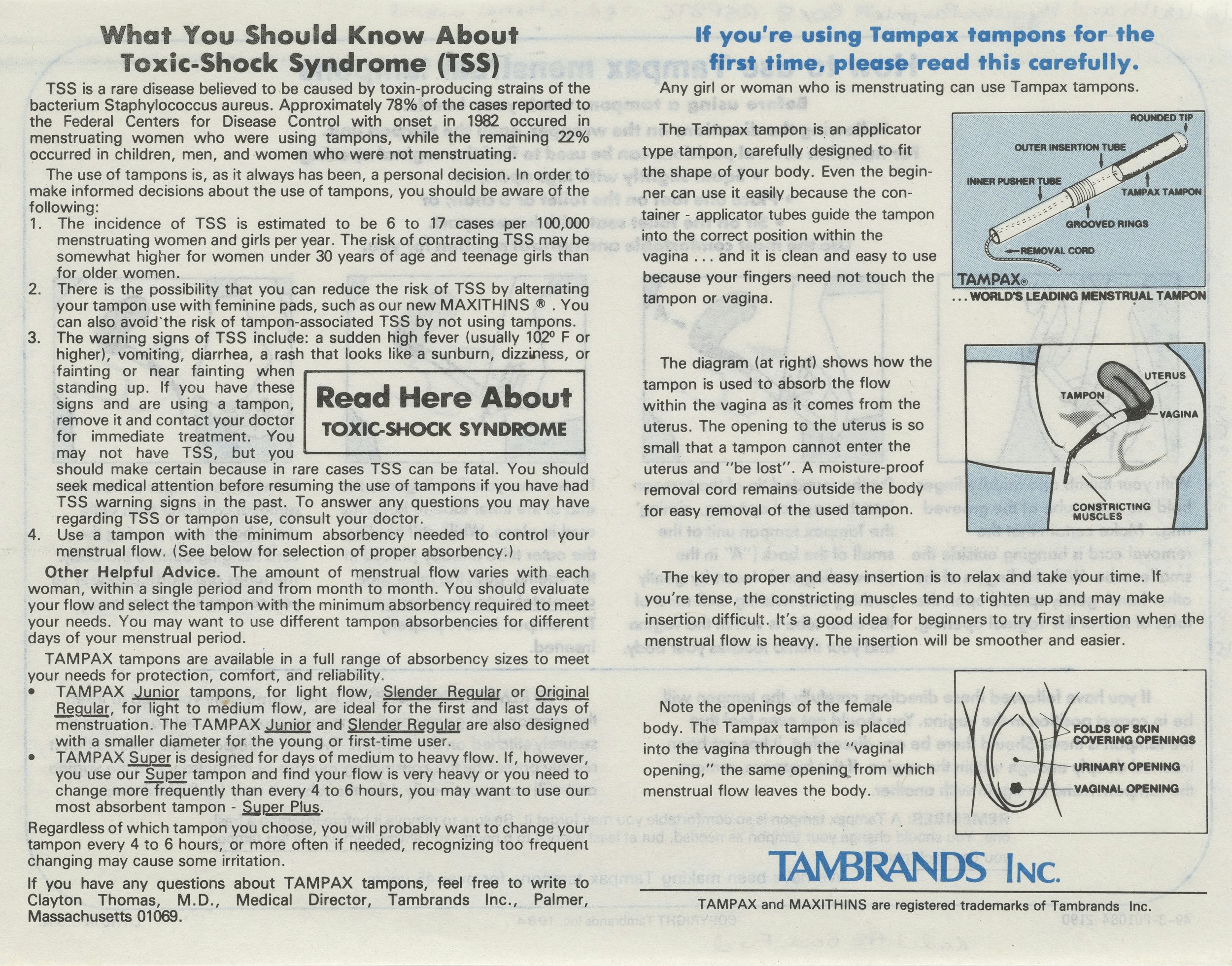

Toxic Shock Syndrome

In a competitive market driven by new materials and innovations in “feminine care,” products claimed to be more absorbent and longer lasting, to provide better protection from leakage, to be more invisible, to mask odors. Procter & Gamble, in competition with the Tampax brand of tampons, marketed Rely tampons in the late 1970s with a national advertising campaign that placed samples in mailboxes across the country. The Rely brand claimed that its tampons, made of polyester sponges, held “up to 17 times their own weight.” Although pads and tampons had been classified as medical devices by the Food and Drug Administration in 1976, and thus required some safety testing, the materials, manufacturing processes, and sizes of tampons remained loosely regulated.

In 1980 the Centers for Disease Control identified toxic shock syndrome, a sometimes fatal buildup of the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus in the vagina. The link between super-absorbent tampons and TSS was made clear in numerous product-liability lawsuits, notably one brought by Michael Kehm in 1982 on behalf of his wife, Patricia Kehm, who had died from TSS in 1980 within a week of using Rely tampons.

The journalist Nan Robertson, a victim of toxic shock syndrome, wrote a 1982 Pulitzer Prize–winning article in the New York Times Magazine recounting her near fatal experience with TSS and the dangers of unregulated materials being used in women’s vaginas. The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective pressured the Federal Drug Administration to adopt a federal regulation to standardize the size and absorbency of tampons across all brands and to limit absorbency to a safe level—well below the level that the FDA had initially proposed.

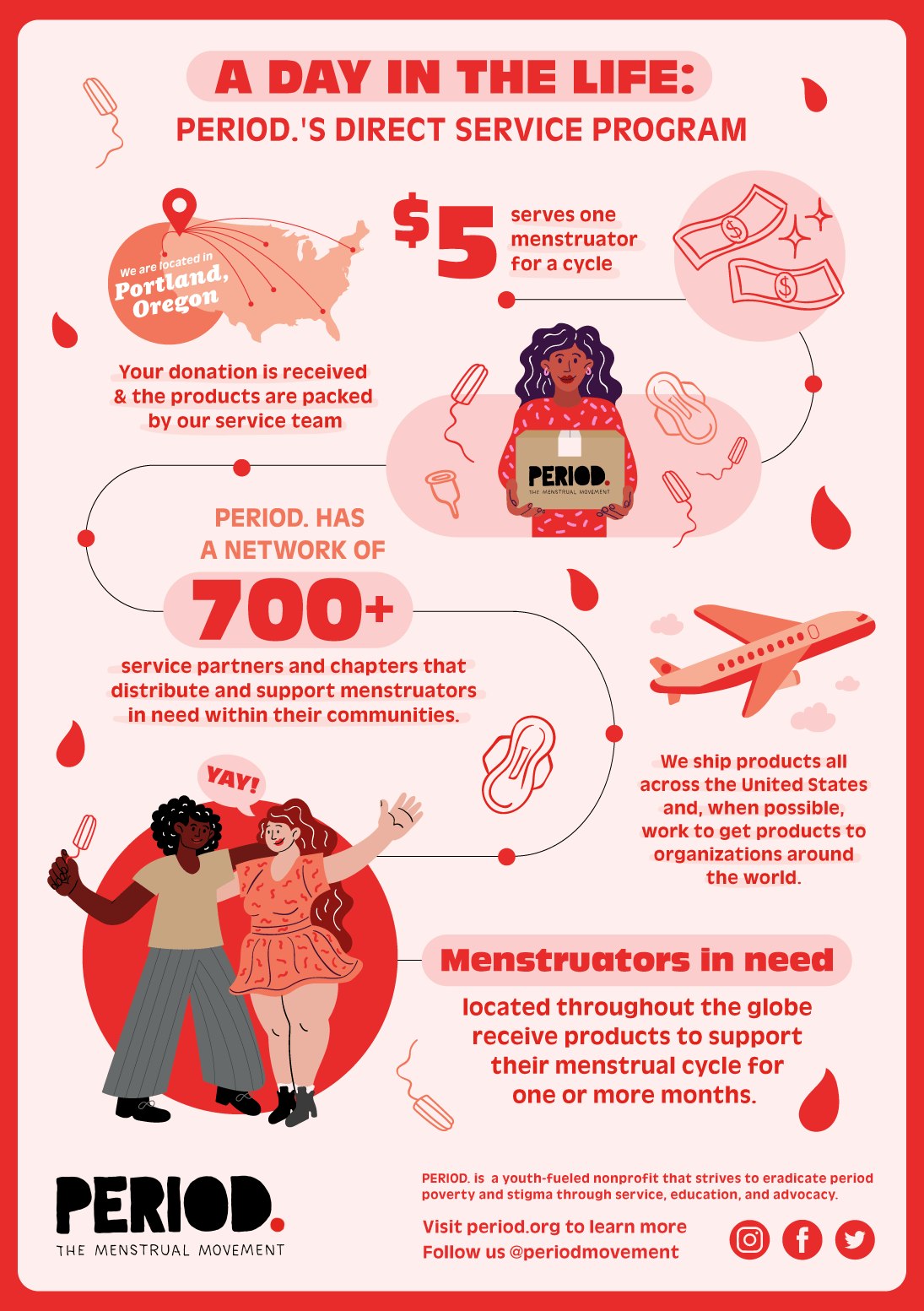

Menstrual Equity Activism

Lack of access to menstrual hygiene products—“period poverty”—affects school attendance, the ability to work, and the physical and mental well-being of menstruators. Spotlighted here are local and national organizations working to guarantee free or untaxed access for all menstruators and to end the stigma surrounding periods by promoting openness, understanding, and accurate information. Legal efforts to widen access to products are growing. Legislation currently under consideration or enacted includes New York State’s 2018 law requiring access to free products in public schools and correctional facilities. In the US more than 140 bills in 37 states promote free products in schools, shelters, and prisons. Youth-led activism in communities and schools is raising awareness, and menstrual advocacy organizations are partnering with companies to donate products or a portion of profits to help fight period poverty around the world. The 2018 short documentary Period. End of Sentence, about women in a village in rural India manufacturing and marketing low-cost menstrual pads, won a groundbreaking Academy Award—the menstrual equity movement’s time has come!

Activist organizations need volunteers to help end period poverty and to provide equal access to all.