A "Grassroots-Driven Sisterhood"

Katherine Turk charts the impassioned early days of the National Organization for Women.

The Women of Now: How Feminists Built an Organization that Transformed America (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2023), by Katherine Turk RI ’19

In her invaluable new history of the National Organization of Women, Katherine Turk reminds us that this venerable institution was founded on “an utterly radical idea: to organize and advocate for all women by channeling their efforts into one association that sought to end male supremacy.” And if, five decades later, this sounds almost naïve, Turk convinces us that the goal was not only admirable but also achievable, at times, in battles large and small. The book’s title, after all, declares that we will learn “How Feminists Built an Organization that Transformed America.” It is a bold assertion, but one that Turk convincingly defends not by aggrandizing NOW’s achievements but by charting the body’s rocky start and recurring challenges—from within and outside its ranks—and the defeats that did much to shape both NOW’s structure and strategy, for NOW’s history, like that of any political movement, is one of missteps and endurance. For example, the first small gathering of potential leaders and foot soldiers in a Washington, DC, hotel suite in 1966 “erupted into chaos,” when attendees disagreed on proposed aims and tactics. Betty Friedan retreated to the bathroom in frustration. But a united front gradually took shape. And although dissent would persist—over such matters as race and gender identity—as would infighting and turf battles, this “grassroots-driven sisterhood,” as one activist described it, survived to become a force that “remade both the Democratic and Republican Parties and reshaped the nation’s political landscape.”

Spanning almost 60 tumultuous years, from 1966 to the present, The Women of NOW provides a succinct but never superficial portrait of a nation in flux. The struggles of the Civil Rights Movement, the Women’s Movement, and the Labor Movement are deftly sketched, as is the right-wing backlash that gained strength particularly during the Reagan era. Yet even as Turk delineates such complex struggles, she returns our attention to three extraordinary women around which this history revolves: Aileen Hernandez, the first woman to serve on the Equal Employment Opportunity Commissionand the child of Jamaican immigrants; Patricia Hill Burnett, a rich Michigan artist, former beauty queen, and lifelong Republican; and Mary Jean Collins, a union organizer with deep roots in the Chicago Catholic community. As different as they could be in upbringing and outlook, each was dedicated to the feminist cause, which they promoted in widely different ways. And their stories both humanize and deepen Turk’s portrait of a fight for equality that continues today. For, as Aileen Hernandez once observed, “All the issues out there are women’s issues.”

Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, and Power behind the Civil Rights Movement (Amistad, 2023), by Tanisha C. Ford RI ’19

The civil rights leader Mollie Moon saw evidence of all issues being women’s issues every day in her rounds as a young social worker, particularly during the 1930s. By 1970, however, when Aileen Hernandez made the above observation, Moon was looking back on a decades-long career as one of New York’s most effective fundraisers and political organizers, although its end was not of her choosing. Regarded as a dwindling force by a new cadre of 1960s activists, she had in fact been ungraciously sidelined. “All around her, Mollie saw women and men who had benefitted from the ground she’d plowed being elevated to national visibility,” the historian and cultural critic Tanisha C. Ford observes. “She likely could not help but feel she had been cast aside long before she was ready.”

In the lively and astute biography Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, and Power Behind the Civil Rights Movement, Ford reinstates this impressive woman at the forefront of the battle for racial equality. In doing so, the author also illuminates an often-overlooked fact: that the civil rights movement was advanced not only in the courts and streets but also at glittering social events that raised that perennial necessity: money. As the initiator of the annual National Urban League Beaux Arts Ball and later director of the National Urban League Guild—described as an “interracial volunteer club of young professional people”—Mollie Moon was the finest persuader in the business.“She knew every Negro of import from New York to DC, Chicago and back, and even some wealthy whites.” Ford writes of Moon as a campaigner who could always find “that sweet spot between sentimentality and social responsibility” that produced a donation.

As daring as she was shrewd, the young Moon spent time in the Soviet Union in 1932 as a cast member of the Stalinist propaganda movie Black and White and worked as a cabaret hostess in Berlin during the rise of Nazism. A fluent German speaker and “a student of Marxist-Leninist revolution” (albeit with “a penchant for opulence”), she later married Henry Lee Moon, a rising figure in the NAACP. And as her celebrity grew, so did the noxious tide of racist/sexist gossip, much of it swirling around Mollie Moon’s fundraising collaboration with Winthrop Rockefeller. (The novelist Chester Himes, who happened to be Henry’s cousin, also repeatedly debased Mollie in his fiction).

Our Secret Society is rich in such details yet never descends into sensationalism or cliché. A memorable tribute to an indefatigable crusader and a keen analysis of the class/race fault lines running through American life, this engrossing narrative is also a reminder that no political cause is flawless. “Historians like me have been trying to disrupt this narrative,” Ford writes, “to show that movements then and now were never simple, never perfect, and never obedient.” The same might be said of Mollie Moon, who died in 1990 at the age of 82 and is now immortalized in these pages.

Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino” (MCD, 2023), by Héctor Tobar RI ’21

The lives chronicled in Hector Tobar’s latest exploration of American society may seem, by contrast, unremarkable. But Tobar shows the opposite to be true. His subjects are in fact the resilient immigrants who buttress an entire system. “We have become the scaffolding of the United States,” Tobar writes of his fellow Latinos, “its plumbing, its daily meal, the roof over the head of its children.” Reviled as “illegals” and worse, they are the indispensable laborers who service affluent enclaves from which they are excluded. As Tobar reports from suburban America, “At the end of the day, the pickups and the maids file out, taking their Mexican and Central American and Caribbean and South American bodies out of these places, and the fleets of bloated SUVs file in, bringing in the lords of these magnificent properties.”

Evocative scenes like this recur throughout Our Migrant Souls: A Meditation on Race and the Meanings and Myths of “Latino,” which is a companion volume of sorts to Tobar’s Translation Nation: Defining a New American Identity in the Spanish-Speaking United States (Riverhead Books, 2005)—although the author is best known for Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014). Here, as before, Tobar challenges common perceptions of identity by tracing the origin of labels such as “white,” “Black, and “Latino,” among other designations. “All race and ethnic categories begin with crimes, lies, distortions, secrets, and myths,” he observes while revisiting, for example, the colonial empires that classified human beings for profit. A nimble writer of immense compassion, this novelist and Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist includes his own experience of returning to his parents’ native Guatemala alongside the reflections of those living in the shadows in America’s promised land. Our Migrant Souls is not only a passionate indictment of history and of current immigration policy but also, and above all, a profoundly moving reminder of our common humanity.

The Vaster Wilds (Riverhead Books, 2023), by Lauren Groff RI ’19

The earliest immigrants to arrive on these shores were, of course, white and quite familiar with “godlessness and murder,” as the narrator of Lauren Groff’s new novel, The Vaster Wilds, knows too well. We meet this English servant in Jamestown, Virginia, where it seems to her fellow settlers that “...there is nothing, only land ... innocent of story. ... A sheet of parchment yet to be written upon.” In the terrible winter of 1609–1610, there is, however, starvation and horror. White people become cannibals. The heroine herself, we soon learn, has committed murder, and as the novel opens, “this starved murderess of a girl” is on the run in the wilderness. From that moment, Groff has us in her grip. We plunge into the forest alongside a fugitive who is exhilarated by escape and yet terrified of the vastness surrounding her: “the cold and the dark and the wilderness and her fear ... all things together, dwindled the self she had once known down to nothing.” She fears all this while sensing, at the same time, that “with no past ... a nothing could be free.”

What follows is a survival story with all the thrills that we expect from such tales: the bear encounter; the ice storm; the suppurating wounds; the foraging for grubs. Groff demands a great deal of her heroine, piling trial after trial on her shoulders. So evocative, however, are the author’s descriptions—of the natural world and of the girl’s inner life––that both the wilderness and human acquire a mesmerizing clarity and depth. “An eagle, as large as a horse, circled in the sky against scurrying low clouds and threw its trembling shadow against the shining face of the river,” the girl observes. And much later, indeed finally, there is the beatific sight of a “lonely heap of cloud in the west, frothing and delicate and whipped and with silvery creases deepening to violet.”

Native people are glimpsed now and then, their presence more potent for being hidden. With similar stealth, nature reveals itself in visionary episodes that transform an adventure into a metaphysical epiphany, although Groff cleverly varies her narrative by returning intermittently to the perilous London life that shaped her protagonist. Like its heroine, The Vaster Wilds has no fixed destination but rather culminates in a lyrical and poignant surrender to nature’s “indifferent beauty,” which in turn bestows a final benediction on a memorable pilgrim.

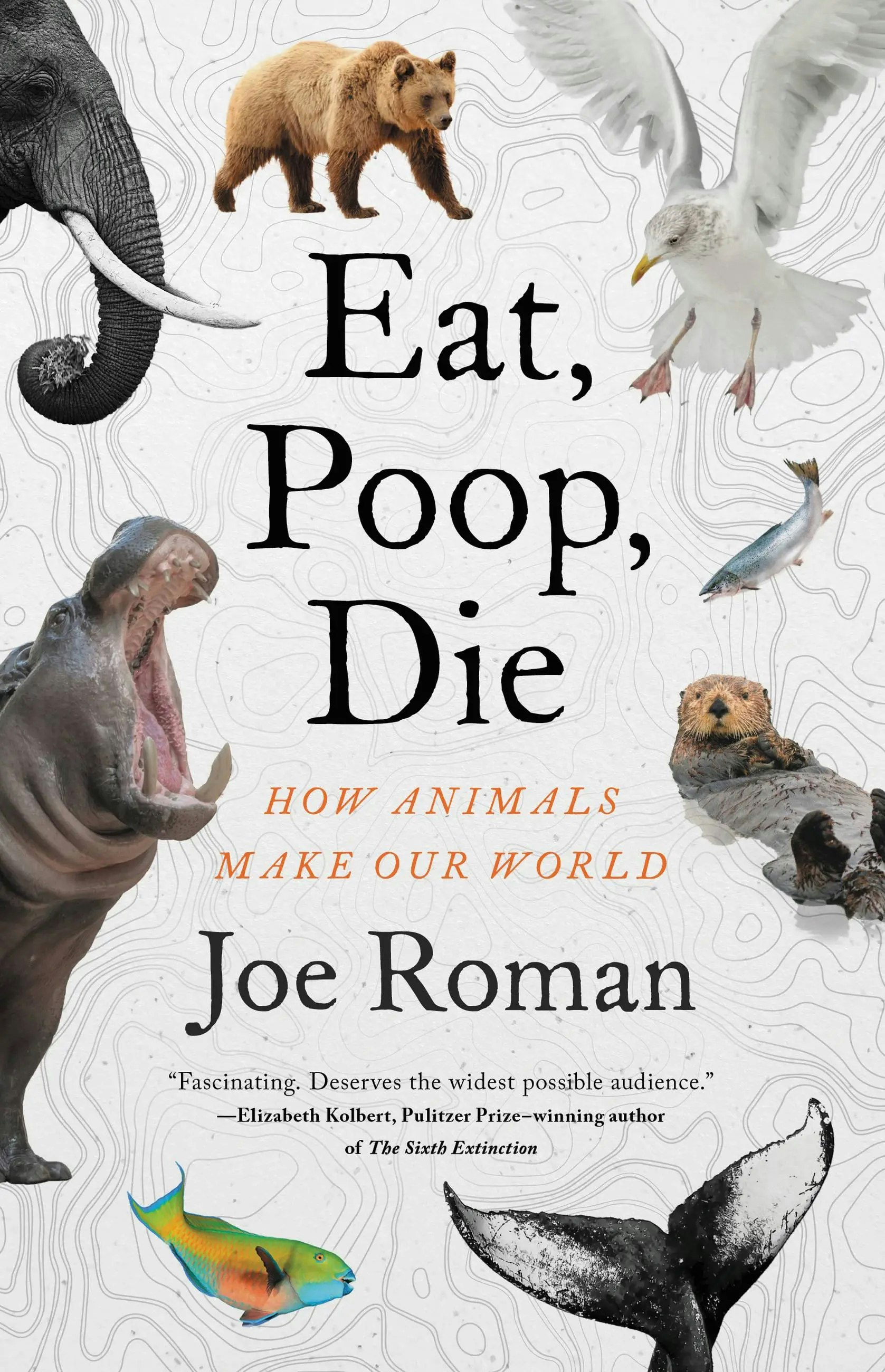

Eat, Poop, Die: How Animals Make Our World (Little Brown Spark, 2023), by Joe Roman ’85, PhD ’03, RI ’23

The natural world in all its complexity is also the subject of Joe Roman’s latest book, although the descriptions by this eminent conservation biologist are more earthy than ethereal. Eat, Poop, Die: How Animals Make Our World is indeed an investigation of all things excretory, from the “fecal plumes” produced by sperm whales and the urine secreted by bears to the waste generated by midges and cicadas. The word “waste,” however, gives the wrong impression. For, as Roman explains, the digestive and life cycles of our fellow creatures literally create the ground beneath our feet—even in vacation heaven. “Most people don’t realize,” Roman writes, “that when they stretch out on a beach in Hawaii, they’re lying on a bed of animal waste.” Hawaii’s parrotfish and corals are among those to thank for this “biogenic sand.” Whales, in the meantime, “transport about a million pounds of nitrogen to Hawaii each winter,” and “more than thirteen million pounds of nitrogen to their breeding grounds in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres each year.”

From Alaska to Florida, Iceland to Zimbabwe, Roman finds evidence of animals shaping—and in many cases protecting—their environment as they process vital nutrients when alive and further nourish the earth when they die. “When the carcass of a big whale hits the seafloor,” Roman writes, “it’s like a blizzard of marine snow, about a thousand years of biomass in one big fall.” Ocean dwellers aid photosynthesis by moving nutrients to the surface; Arctic seabirds expel ammonia that forms droplets at cloud level thereby keeping the region “a little colder”; salmon and bears enrich the forests. At every turn, the continued existence of a planet on which humans can survive depends on the ceaseless industry of animals, leviathan and the minute.

An erudite and engagingly witty journey through nature’s marvels, Eat, Poop, Die reveals above all the astonishing complexity and fragility of our shared Earth, the urgent need to conserve what remains and, in some cases, to restore what may otherwise vanish. So much of the work is already being done for us. “As birds and whales do at sea, bison build grassland by choreographing the green wave,” Roman explains, “spiders boost primary productivity in meadows by spinning a landscape of fear, and sea otters build kelp forests by keeping sea urchins at bay.” Even the most remarkable humans are, in other words, a small part of the picture.

Anna Mundow is a writer in central Massachusetts.