Busola Banjoh Redefines What It Means to Be Black at Harvard

An undergraduate researcher at the Initiative invests in the University community—and helps create a more inclusive campus.

For Richard Theodore Greener and Alberta Virginia Scott, the first Black graduates of Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges, respectively, being the only African Americans in an otherwise white class was often an isolating experience. Yet, despite the racial biases of the times, it did not deter them from achieving their educational pursuits. Thanks in part to their resolve, generations of students of African, Caribbean, and African American descent have not only graduated from Harvard and Radcliffe but have helped knock down barriers that once made it impossible for them to believe—in the words of W.E.B. Du Bois—that they were “of Harvard.”

Fast forward to Busola Banjoh, a double concentrator in history of science and African and African American studies. For the Georgia native, being Black and “of Harvard” means participating in the kind of community that Greener and Scott were denied. Community is why Banjoh, who applied to and was accepted at more than a dozen of the nation’s top universities and colleges, chose Harvard. After speaking with Black students and a Black board member, she came to Cambridge firm in the belief that it was a community that would support and nurture her.

From the start of her time at Harvard, Banjoh made a commitment to invest in the University’s Black community. That has included the research she helped conduct for the Presidential Initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery (H&LS). Throughout 2021, she was a research assistant supporting the initiative’s subcommittee on the history of medical education and experimentation, exploring evidence of racism at Harvard Medical School and pulling together a database of images that might be used to illustrate relevant sections of the historic report Harvard will release this spring.

“The experience enabled me to connect with different people from different backgrounds who all have a commitment to addressing these untold stories and histories,” Banjoh says. “I feel like I know more about different aspects of Harvard.”

During her freshman year, in 2018, Banjoh served on the board of the First Year Black Table, a group of Black freshman members of the university’s Black Students Association. When the then-sophomore Andrea Bossi asked whether she was interested in brainstorming ideas for a mentorship program that would connect Harvard’s Black undergraduate and graduate students, her answer was a resounding “Yes!”

A few weeks later, Banjoh, Bossi, Karl Kumodzi, and Akiesha Ortiz were creating the framework for what is now known as the Greener Scott Scholars Mentorship Program (GSS).

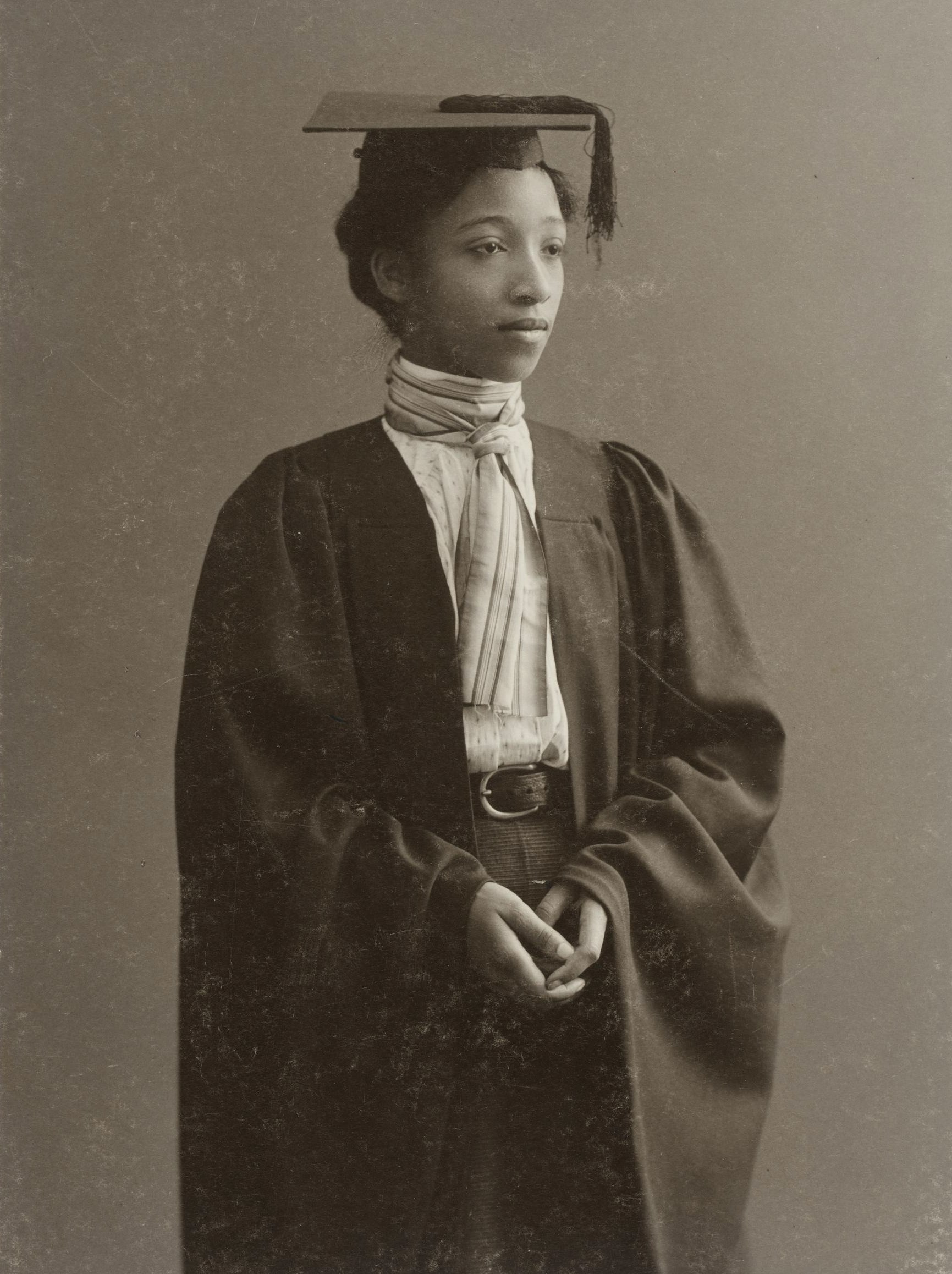

Alberta Virginia Scott (1876–1903) was the first African American graduate of Radcliffe College. Scott graduated with distinction from the Cambridge Latin School in 1894 and entered Radcliffe, graduating in 1898. Photo courtesy of Radcliffe College Archives Photograph Collection

“When thinking about what being Black at Harvard means, we thought about the trailblazers who made being Black at Harvard possible, and we thought it right to pay homage to Greener and Scott,” Banjoh says. “It’s always hard being the first, and I can’t imagine what being first meant when they were at Harvard, given the social climate in United States and at the University.

“At the same time,” she adds, “By virtue of being trailblazers and being able to see that greater vision of what an education at Harvard could bring to not just themselves but to their communities really embodied what community building could be—the importance of education and of being yourself unapologetically and showing up as your true self despite any limitations and hardships imposed on you. They made monumental change.”

The GSS founders created a “very long and meticulous” application process to pair students with mentors, which considers commonalities and the ways a mentee wants to grow and develop. Considerations include how much hands-on attention is required, the specific goals to be achieved, and other benchmarks.

“We had a vision of what we coined a soulful program that would go beyond the academic and professional aspects of mentorship to address students’ mental, spiritual, emotional, and overall well-being,” Banjoh says. In addition, they believed that the graduate students’ proximity in age to their mentees and professional successes would help mold the underclassmen’s academic careers.

The program, which now includes an executive leadership board, swiftly grew from 50 matches in its first year to 80 in its second. By its third year, when Banjoh served as GSS president, matches grew to 110.

Richard Theodore Greener (1844–1922) became the first African American graduate of Harvard College in 1870. He would go on to be the first African American professor at the University of South Carolina and then the dean of the Howard University School of Law. Photo courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

In addition to mentorship, the organization also offers in-person and virtual events, including inspirational talks with such distinguished speakers as Cornell William Brooks, the Hauser Professor of the Practice of Nonprofit Organizations and a professor of the practice of public leadership and social justice at Harvard Kennedy School; LaTosha Brown, cofounder of the Black Voters Matter Fund; and Gavin Moses, a local Black poet. Other events have included a dance workshop led by a graduate student from the Harvard Chan School “to elevate love, joy, and creativity” and discussions with graduate students who shared their journeys to Harvard, the advice they got, and the advice they would carry forward.

“We have found a lot of different ways to connect students as a cohort, and active, creative, and personal ways to think about growth and being a Black student at Harvard and what that means to us,” says Banjoh.

For her, it’s about the intersectionality of being not only Black but also a dark-skinned woman who is Nigerian American. “It comes down to leaving a legacy and helping to create and cultivate a narrative of strength, resilience, and individuality.”

Banjoh’s legacy will extend beyond her GSS work. As a result of her participation in H&LS, she met Evelynn M. Hammonds, chair of the Department of the History of Science, the Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science, and a professor of African and African American studies, and Udodiri R. Okwandu, a doctoral candidate in the Department of the History of Science. Hammonds and Okwandu became advisors for Banjoh’s thesis on the absence of colorism in studies of the impact of racial microaggressions on Black Americans.

According to Banjoh, participating in the initiative deepened her understanding of the nuances of being at Harvard. And as a pre-med student, it reinforced for her the importance of emphasizing Black communities in all of her work. “I would say that’s how I felt before, but this experience really highlighted the importance of continuing this work,” she says.

Fascinated by the history of science, Banjoh relished the opportunity to help fill gaps in understanding, “help tell the stories of those who have been forgotten or overlooked, and give a more complete story of the history of those who have been memorialized and held on a pedestal.” She hopes the faculty committee’s report, when it is released this later spring, will help create a more inclusive campus, spark difficult but necessary conversations in and outside of Harvard’s classrooms, and lead professors to think about how enduring legacies of slavery at Harvard impact students and staff today in different ways.

“I am happy that Harvard’s legacy of slavery is being talked about on an institutional level and supported by faculty and staff,” Banjoh says. “Black students, faculty, and staff will feel heard, cared for, and more understood with the release of the report. It will also benefit non-Blacks to engage in this history and untold story and hopefully bring about feelings of conviction and movement to engage in this greater conversation and discourse.”

Knowing what she knows now would Banjoh have made the decision to come to Harvard?

“I would 100 percent still have come to Harvard. I think that this work really showed me that it’s not just a Harvard issue but an academia and institutional issue. And to be able to help uncover these stories here at Harvard has really reinforced that nothing’s untouched—so I am happy with my choice and to be able to come to this conclusion at this school.”