Everyday History

How one teacher is using the Schlesinger collections to personalize American history

Every day, the first five minutes of Marlin Kann’s class at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School are devoted to journaling. That may not seem particularly unorthodox—until you consider that he teaches the school’s Advanced Placement US history course.

The journaling exercise is one of the many ideas that took shape during the six weeks that Kann spent in the Pforzheimer Reading Room this past summer, after winning a Research Support Grant from the Schlesinger Library for a project to rethink the canon of US history document readers. “From my perspective, sometimes these document readers reinforce that history is of a certain group: of the elite, of white men,” he says. “I wanted to swap it out for stuff that was more equitable in its representation of who takes part in history.”

Once he started going through the sources, however, Kann had an epiphany: choosing new, more representative readers would simply be leading his students in his own chosen direction, which posed a new problem. “I was also not doing service to the documents themselves or to the people who created them—to these agents of history,” he says. He had to shift his focus.

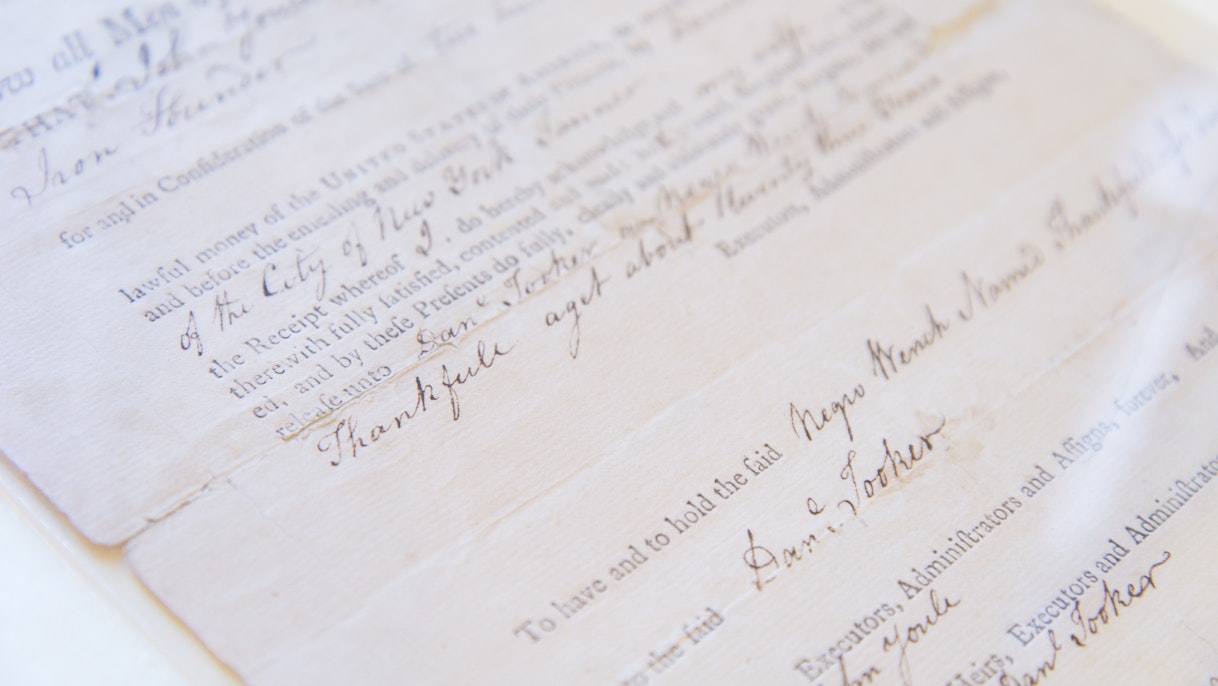

Unboxing History: Thankfull

As Kann looked around the reading room, he saw professional historians doing their own research—and, he says, “it looked a lot different from what happens inside a history classroom.”

Kann decided to connect his students with history through the photo albums, cartoons, magazines, letters, and journals found in the archives, each more powerful than the last. The prisoners of war whose private accounts made their way into the library’s collections didn’t think of themselves as making history, but their writings are an invaluable resource to researchers today. He sees his own students’ journals—which he does not read—as a potential resource for historians of the future. He wants the students to recognize that they’re making history every day. “It’s important for students to see that,” says Kann. “It gives them more agency to know that they’re not just microbes in this world, to know that their lives matter.”

After his weeks in the Schlesinger, Kann—who earned a master’s in history from Florida International University—created the Schlesinger Miniature Archive, which allows students to explore history in a manner that more accurately represents how historians do their work. He began by thinking about time periods in American history and themes evident during those times; then he identified historical examples that would allow the students to relate to those themes. He scanned hundreds of illustrative documents from the library’s collections—all of which are available to his students through Google Classroom. “They can experience an abbreviated version of what it’s like to sit in the reading room and do history,” he says.

Kann’s mini-archive is minimally processed, he says, but it’s still curated. As he built it, he selected items that from his perspective provide “the most potent representation of themes, trends, or human agency.” He strove to strike a balance between a sense of grand scale and the personal high stakes of history, all while promoting skill-based learning goals. “One of the skills I’m working on developing is how to extract and apply material,” says Kann. “It’s exciting to just let them explore the archive—it doesn’t matter where they go with it, because it’s all real and relevant to what we’re talking about in class.”