Dear Friend and Fellow Laborer

Schlesinger acquires correspondence of Rebecca Primus, 19th-century African American schoolteacher

Adele Murry had plenty of time to write letters while living in Bangor, Maine, in 1860. But letter writing may not have been what she preferred to do. “I have often thought of what you wrote about the entertainments that the people of color [have] in Hartford,” she told a friend, 24-year-old Rebecca Primus, the eldest child of an African American family well established in Connecticut’s capital. Murry envied Primus her membership in several sewing and reading circles. She herself didn’t belong to any and never had. In Murry’s day, Bangor was a thriving lumber port and shipbuilding boomtown, but, she complained, there were “so few people of color . . . that no such pleasures [were] afforded.”

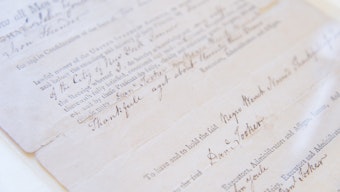

At an auction this past March at Swann Galleries, in Manhattan, the Schlesinger Library acquired a rich cache of correspondence written to Primus (1836–1934) by Murry and other friends as well as by family members. This collection of 41 handwritten missives presents only one side of each conversation. To learn the whole story, research will have to be done and interpretations made. But even without that scholarship, these newly discovered pages are a treasure. A rarity in the realm of historical documents, which invariably favor the doings of privileged white men, they are a record of ordinary life as lived by young, educated, middle-class African American women from pre–Civil War days through Reconstruction.

In 1999, the Columbia University professor Farah Jasmine Griffin published Beloved Sisters and Loving Friends: Letters from Rebecca Primus of Royal Oak, Maryland, and Addie Brown of Hartford, Connecticut, 1854–1868 (Knopf), a study based on letters at the Connecticut Historical Society written by Primus to her family (including her cat, Little Jim), along with ones to Primus by Brown, a domestic servant. Primus and Brown had an erotic relationship. An 1857 letter by Eliza of Springfield, Massachusetts, which came as part of the Schlesinger’s new acquisition, provides evidence of another Primus relationship that was at least romantic. “I feel so lonesome without you,” Eliza writes, asking Primus for a portrait, just a small one, since “you know begers [sic] must not be choosers.” In a while, Eliza writes again, forlornly: “I have not received no letter from you. I have dreamt about you every night since you been gone.”

Eliza reports that “Fred Douglass” will lecture in Springfield “on the signs of the times in view of the Dred Scott decision.” The US Supreme Court had handed down its judgment three weeks earlier. Eliza’s mention of current events is anomalous content for this batch of letters. The Civil War itself is given short shrift: One correspondent does mention the Union’s first official all–African American unit, the “poor soldiers” of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, remarking that “richly have they earned the encomiums of the Old Bay State.” Another describes a “dreadful riot” in Jersey City in August 1863, during which gangs “sallied forth in quest of colored people threatening to hang all they found.” Undoubtedly a draft riot, it prompted the terrified correspondent, her landlady, and her family to find refuge with “some of our white friends in the neighborhood.” More commonly, the writers are caught up in exchanges about their personal joys and sorrows, but that is precisely where the value here lies.

Primus was trained as a teacher. In 1865, when she was 29, the racially integrated Hartford Freedman’s Aid Society sent her to Maryland to establish a school. While living and working in the Eastern Shore community of Royal Oak, she formed a network through the postal service with women who had been sent elsewhere in the upper South as part of this experimental enterprise, bringing literacy to formerly enslaved people. “Dear Friend & Fellow Laborer,” one of them writes Primus. “How are the whites in your town, friendly toward the colored people? Isn’t that Trappe [Maryland] a horrid place? It seems no teacher can remain any length of time there. I [heard] there have been four teachers there since I left.” Another wonders if her school will close, since it is so poorly attended. “The children come on slow learning their peices [sic], and I myself do not feel as much interest in the affair as I should, I will have to spur up and be more energetic or it will be a sad failure.”

A correspondent who signs herself “Josephine” was, like Primus, originally from Hartford and sent to teach in a community on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. She is Josephine Booth, identified in Beloved Sisters. Booth writes Primus in 1869 about how the religious revival sweeping the country has adversely affected students: “They go to the meetings at night, can’t study during the day.” The most philosophical of the Primus pen pals represented here, Booth tells Primus on another occasion, “It takes time to do anything well and especially in this thing called civilization.”

Swann Galleries is not at liberty to reveal the consignor of these letters, whose stamped and postmarked envelopes, with intriguing scribblings on their backs, were intact. So we do not know where they came from or—thrilling idea—whether more are forthcoming. Wyatt Houston Day, in 1996 the founding organizer of the auction house’s Printed & Manuscript African Americana department, could say only this: “Things turn up in the most unlikely places. So much [African American history and its artifacts] got ignored, covered up, lost, forgotten, or destroyed. There were sins of commission and omission. You have things just squirreled away.” Day—whose aunt, incidentally, was the activist Dorothy Day—said one of his original hopes for the department was to establish a market and prices for this material. “And prices are important, because they’re an incentive for people to preserve things.” His other hope was “that it would coax stuff out of attics and basements and dresser drawers, which it has most effectively done.”

Schinto has been an independent writer since 1973. Since 2003, she has been reporting on auctions and trends in the antiques trade for Maine Antique Digest. Her papers are housed at the Schlesinger Library.