The Unsugarcoated Truth

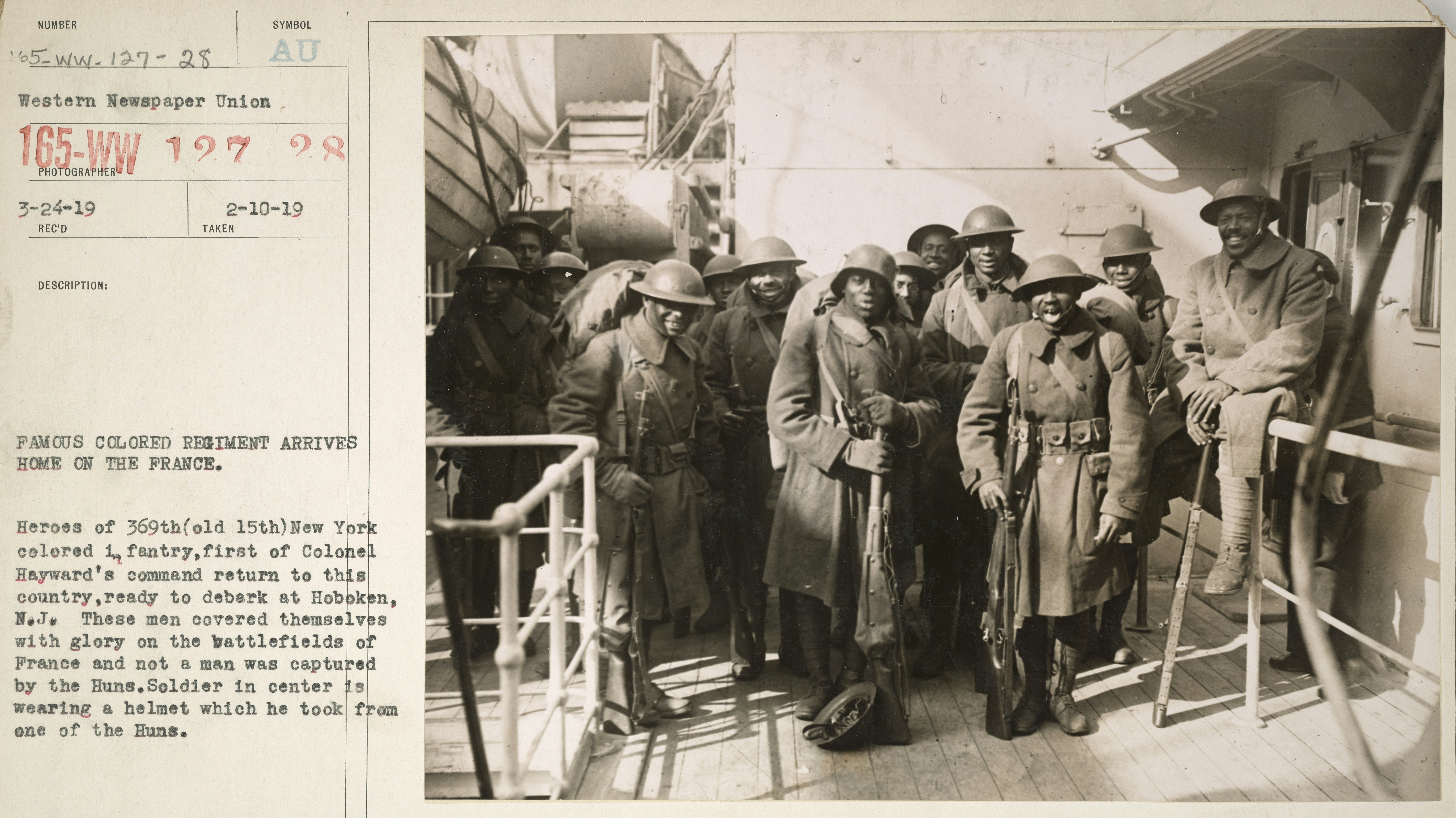

Chad L. Williams mines W. E. B. Du Bois’s unfinished life’s work.

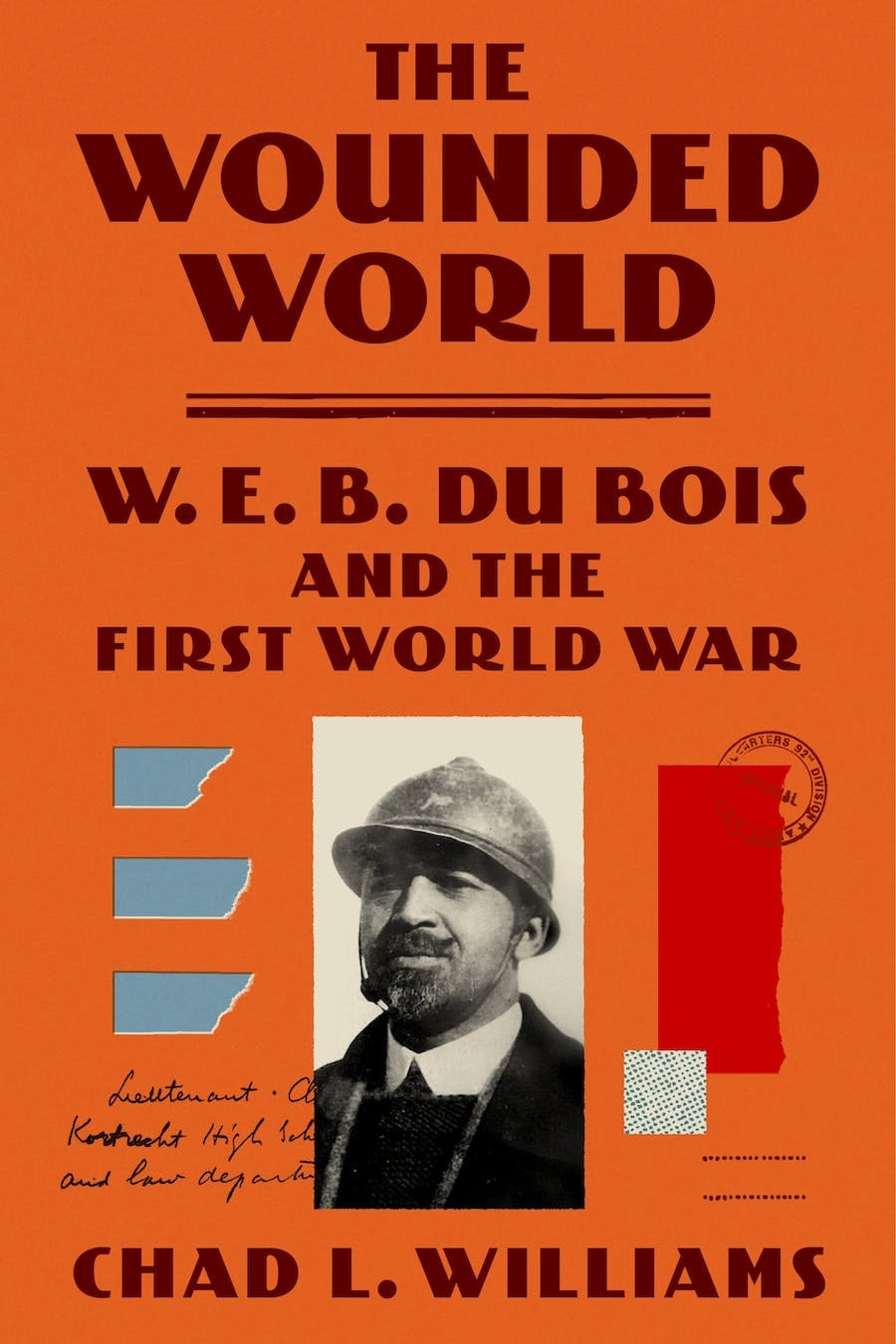

The Wounded World: W. E. B. Du Bois and the First World War (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023), by Chad L. Williams RI ’18

In this erudite and engrossing chronicle, Chad L. Williams sets himself the difficult task of documenting a failure while telling a story of astonishing achievement. More specifically, Williams traces the fascinating history of a book that was never completed and never published but that nonetheless constituted the life’s work of one of the greatest scholars of the 20th century.

First arising as a topic in the late 1910s and occupying the mind of its author, W. E. B. Du Bois, until his death, in 1957, “The Black Man and the Wounded World” was a monumental account and analysis of African Americans’ experiences in the First World War, much of it based on verbatim accounts and wartime journals. Beginning in 1919, Du Bois sent out the call for “personal narratives ... citations and decorations for bravery ... photographs and scenes from life at the front” through the NAACP’s monthly magazine, the Crisis. And African American readers eagerly responded. Within months, the archive of original documents grew impressively—and dauntingly—as did the “small, paper-thin index cards” that Du Bois used to cross-reference such topics as “unfair restrictions placed on colored soldiers.” The aim, after all, was not accuracy alone, but truth.

“Whereas other books offered valorized, uncritical accounts of the Black war experience,” Williams writes, “Du Bois’s work would not sugarcoat.”

Nor does Williams. Indeed, his restrained descriptions of the humiliations, injustice, and brutality inflicted on African Americans fighting overseas, and of the endemic savagery they returned to in the “shameful land” of America, infuses The Wounded World with pain and horror. Men are burned and dismembered as spectators cheer. Black body parts are distributed like party favors. “This is the country to which we Soldiers of Democracy return,” Du Bois fumed in 1919, insisting that, “we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.”

That battle is one of many—personal and political, noble and vindictive—that The Wounded World encompasses and that Williams describes with acuity and compassion. The resulting portrait of the prodigious writer best known today for The Souls of Black Folks (1903) is fittingly one of light and shadow, of optimism and disillusion, but most enduringly of moral courage and intellectual rigor. “After all, our problems are not to be solved by emotions,” Du Bois wrote in 1932, “but by deep concerted intelligence.” The following year, however, Adolf Hitler would become chancellor of Germany, and Du Bois would witness another worldwide conflagration that would sorely test his core belief in reason.

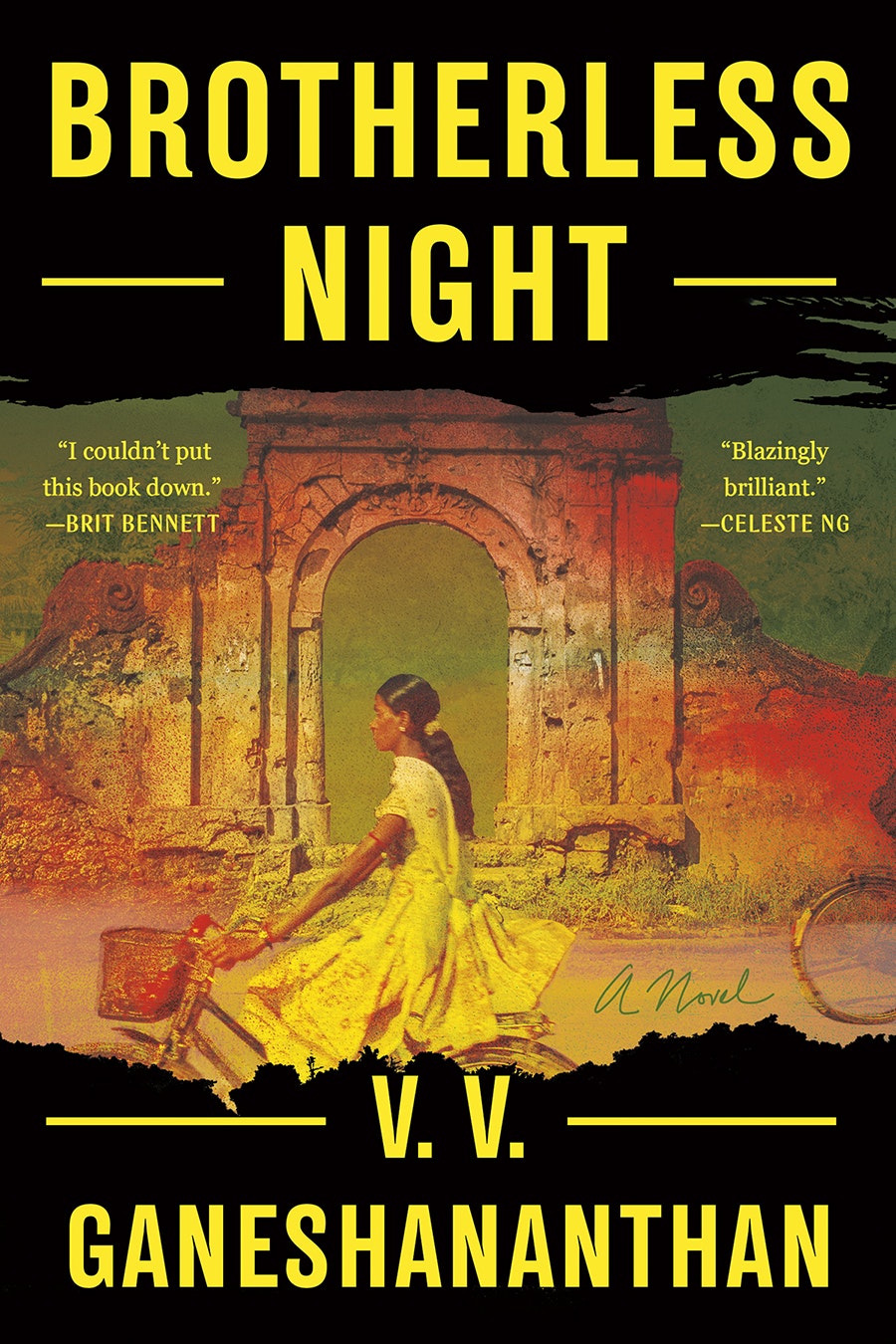

Brotherless Night (Random House, 2023), by V. V. Ganeshananthan ’02, RI ’15

A more intimate war dominates V. V. Ganeshananthan’s deeply affecting novel of love and loss, which is set in the author’s native Sri Lanka during the tumultuous 1980s. “I met the first terrorist I knew when he was deciding to become one,” the narrator, Sashikala—Sashi to her loved ones—begins as she introduces us to the young man whose family, like hers, lives in “one village of the Tamil town called Jaffna.” Referred to only as “K,” Sashi’s neighbor is a serious 17-year-old who dreams of becoming a doctor but who will instead be drawn into the struggle of the country’s Tamil minority to win a separate homeland for their persecuted people. The two meet almost melodramatically in 1981 when K, passing Sashi’s house, hears her screaming and rushes inside to help. She has burned herself badly while making tea, and K soothes her flesh with raw eggs. It is a wonderful scene, rich in detail and significance. Sashi, in agony, sees only K’s fingers, “working in and out of the eggshells, scraping the slime of the whites cleanly onto the swelling rawness.” In the aftermath, she is struck by the certainty underlying his competence. Yet, in just six years’ time, K will be the one calling on Sashikala to attend to his ailing body:

“You owe me a debt,” he said, trying to sound light, although clearly none of this was casual.

“What debt?”

“You were my first patient, of course,” he said.

Sashi has, by then, seen her four brothers swept along on the country’s surging tide of political violence. She has witnessed mothers confronting the soldiers who have taken their sons prisoner. As a medical intern, she has treated a pregnant rape victim who will soon take her own life as a suicide bomber. None of which she can imagine when, as a teenager, she implores her older brother to choose university over armed struggle. “You want to go on in some sort of peaceful life,” he gently admonishes her, in response, “but there was never a peaceful life. That was a myth.” In this heartfelt novel, the truth of that conclusion is inescapable. Yet the note of loving tenderness that the author strikes in the captivating early scenes of Brotherless Night cannot be drowned out—not even by warfare. Indeed, when K tells Sashi, “I would have spent the other life with you,” it seems that hatred, in that moment at least, can be vanquished by love.

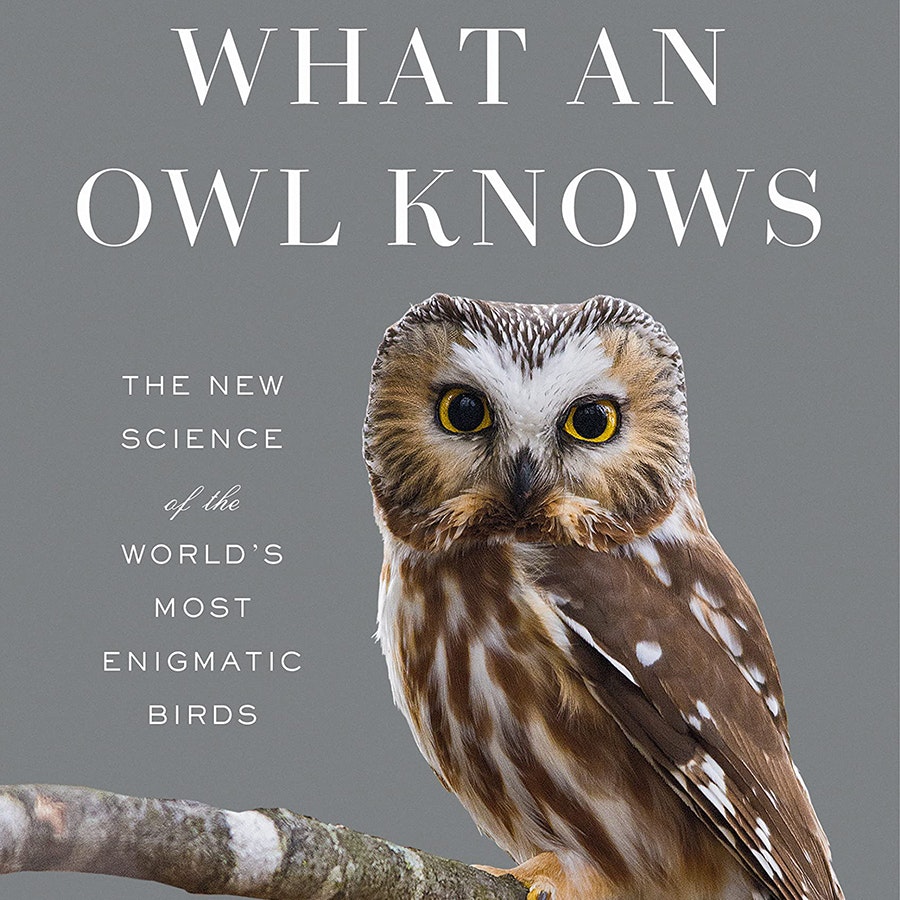

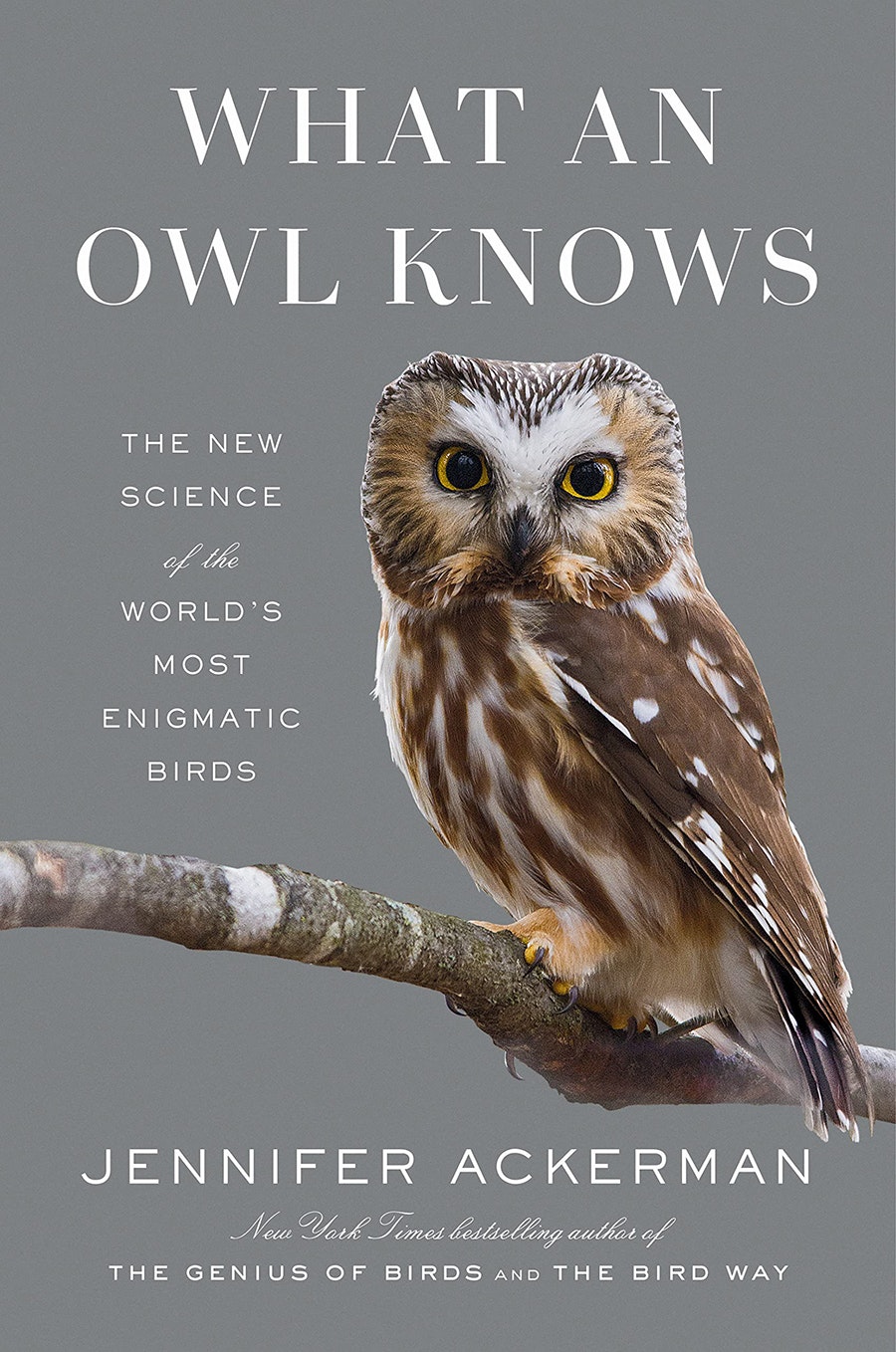

What an Owl Knows: The New Science of the World’s Most Enigmatic Birds (Penguin Press, 2023), by Jennifer Ackerman BI ’98

The night world so vividly evoked in Jennifer Ackerman’s new book is the sovereign terrain of one of nature’s most remarkable hunters. Described here as “muscle covered in velvet,” the owl is silent, swift, and accurate. (p 100) Just how accurate, we are only now beginning to learn, thanks to satellite and drone technology, among other advances. “Groundbreaking work on owl senses is shedding light on the superpowers that allow these birds to find their prey,” the author writes in her preface, “ ...their superb night vision and hearing ... their near-soundless flight—adaptations that make owls a pinnacle not just of the food chain, but of evolution itself.”

An engaging and often witty science writer, Ackerman describes such breakthroughs and experiments in lively detail. “Nest cams expose the sometimes nasty, sometimes charitable dynamics between siblings,” she writes of one study. “Nestling barn owls, for instance, are known to give food over to their younger siblings, on average twice per night.” The personalities of the many wildlife biologists engaged in owl research are also deftly sketched, in scenes that range from the comical to the ethereal. “If you practice that religiously for about two weeks,” one biologist says of learning owl calls, “you can actually start to fool a male Flammulated Owl. And that’s a head trip, because once you get one of these ... to respond to you? Man, you start to feel like you’re growing wings.”

There is as much to wonder at as there is to learn in What an Owl Knows. And it is Ackerman’s skill in striking that balance that draws us into the astonishing world—and brain—of a creature that has fascinated humans from the dawn of consciousness.

“One day some thirty-six thousand years ago,” the author writes of prehistoric France, “an ancient member of our species walked into the Chauvet Cave... [and] with a finger, carved in the soft yellow surface of the rock a fine image of an owl...” (p 234) The cave painter could not have known that there eventually would be some 260 species of owl on earth (ranging from the enormous Eurasian Eagle Owl to the finger-sized Elf Owl) or that these birds would one day range from Peru to Siberia, having first arrived on Earth during the Paleocene epoch, 55 to 65 million years ago. That knowledge, and more to come, is ours today. But the mystery remains undiminished. “That owl seemed like a messenger from another time and place, like starlight,” Ackerman writes of a wild bird that she briefly held while it was banded. “Being near her somehow made me feel smaller in my body and bigger in my soul.

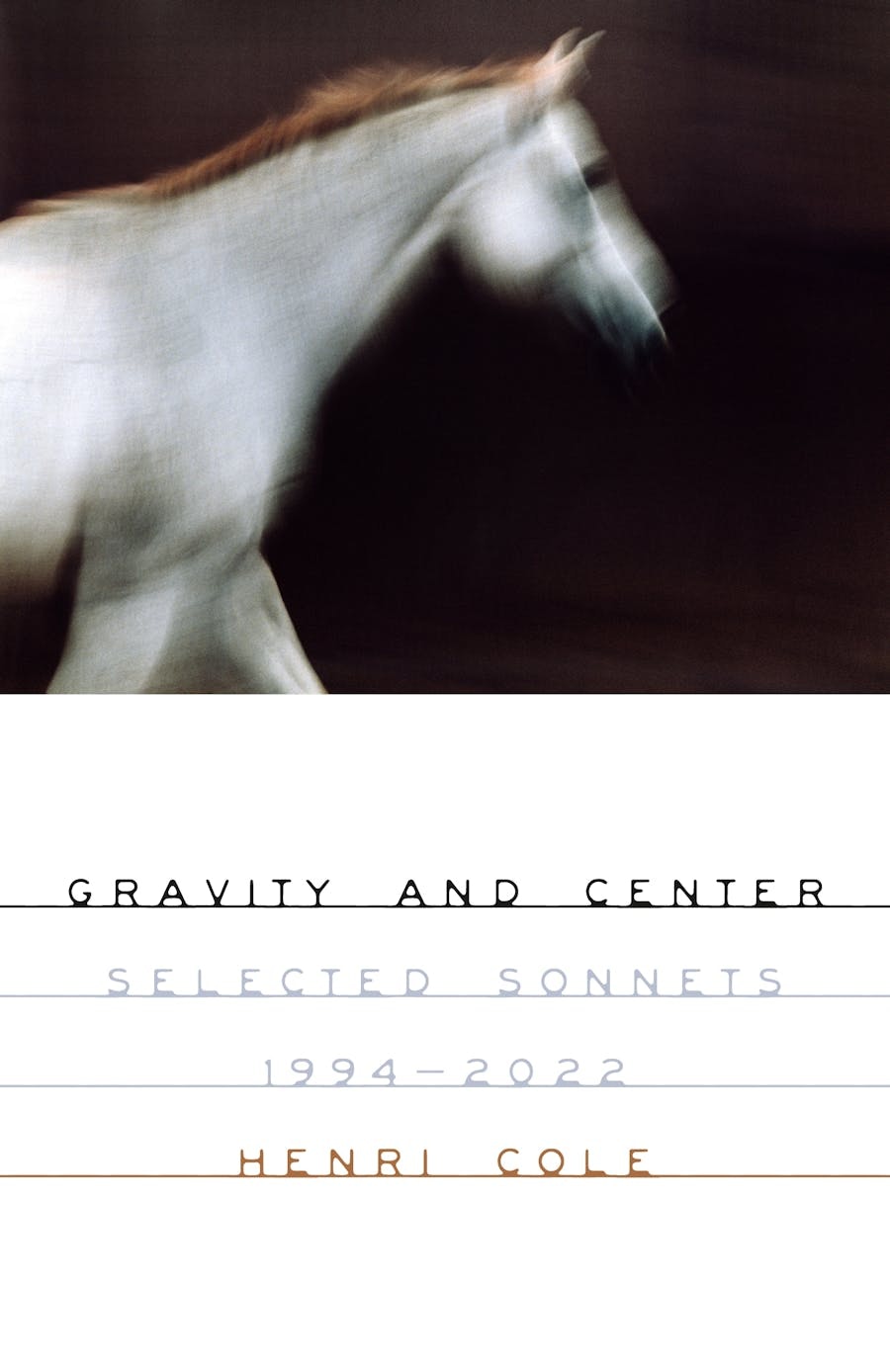

Gravity and Center: Selected Sonnets 1994–2022 (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023), by Henri Cole RI ’15

In the afterword to these new and selected poems, which span 30 years of work, Henri Cole recalls “living in the foothills north of Kyoto” two decades ago and desiring to “write poems that conveyed the intensity of my life there.” A quiet intensity, to be sure, as it was centered on the tea ceremony that Cole was studying at the time. The sonnet, “with its mix of passion and thought” seemed to him the perfect form. And so, indeed, it proves to be here as, within that structure, Cole captures not only the stillness of a halted moment but also, encasing all such moments, “the tragic situation of the individual in the world.”

With titles such as “Carwash,” “Recycling,” “On Peeling Potatoes,” and “Mouse in the Grocery,” some poems are conversational in tone. One begins, for example, “There are no bacon strips this morning / so a mouse ponders a pound of sugar.” And all emit the zest of whimsy that can leaven a mundane or even a tragic reflection. Whatever the subject, grandeur—like grief—typically lies in wait. “Embers,” for example, opens with “Poor summer, it doesn’t know it’s dying. / A few days are all it has...” and ends with an image of pine trees at night, holding “their arms out as God held His arms / out to say that He was lonely and that / He was making Himself a man.” Time and time again, the natural world collides with its most successful—and destructive—species. With often comical results, as in “Face of the Bee,” which captures the following fleeting moment: “Staggering out of a black-red peony, / where you have been hiding all morning / from the frigid air, you regard me smearing / jam on dark toast. Suddenly, I am waving / my arms to make you go away. No one / is truly the owner of his own instincts, / but controlling them—this is civilization.”

Anna Mundow is a writer in central Massachusetts.