Events & exhibitions

exhibition

It’s Complicated: 375 Years of Women at Harvard

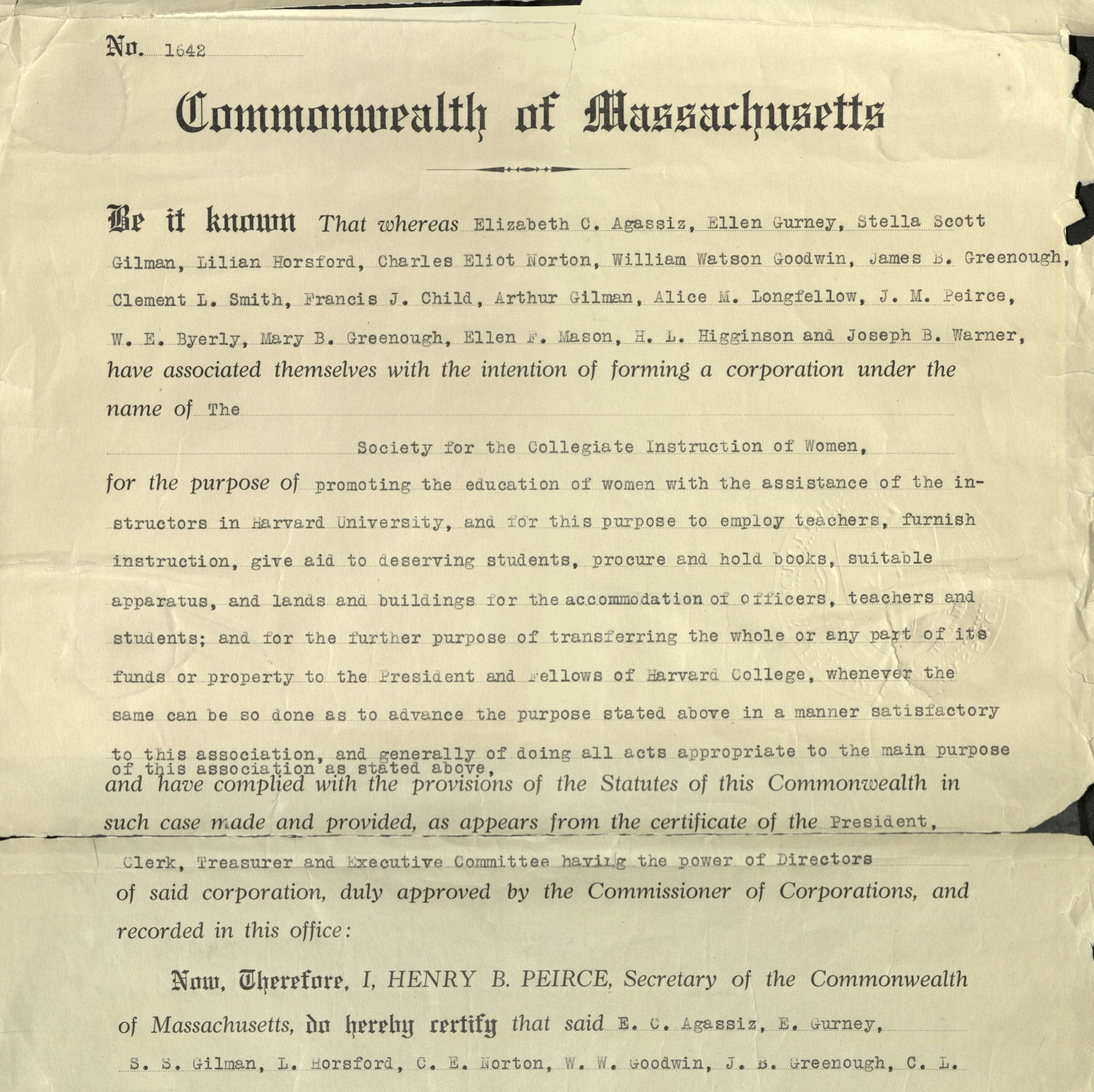

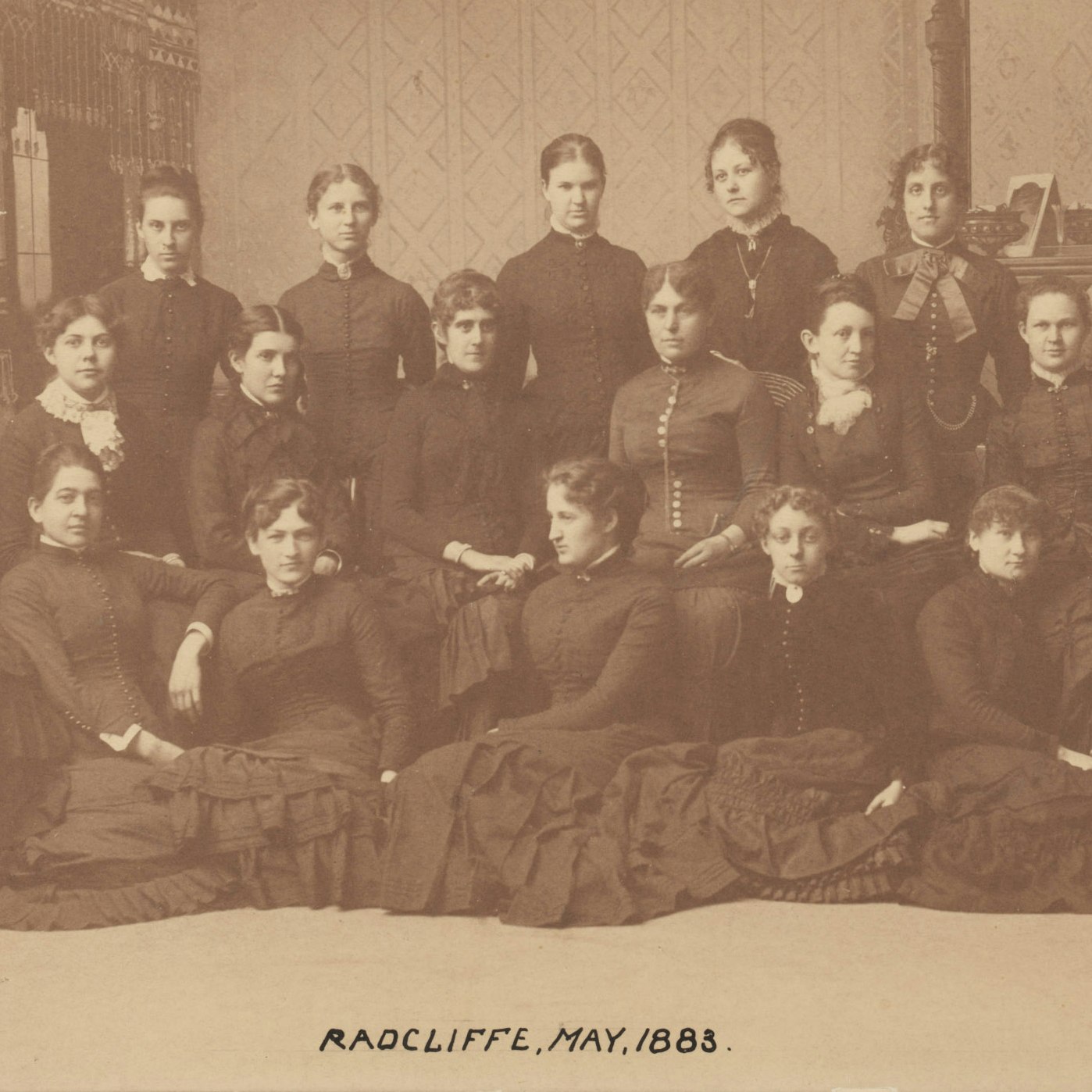

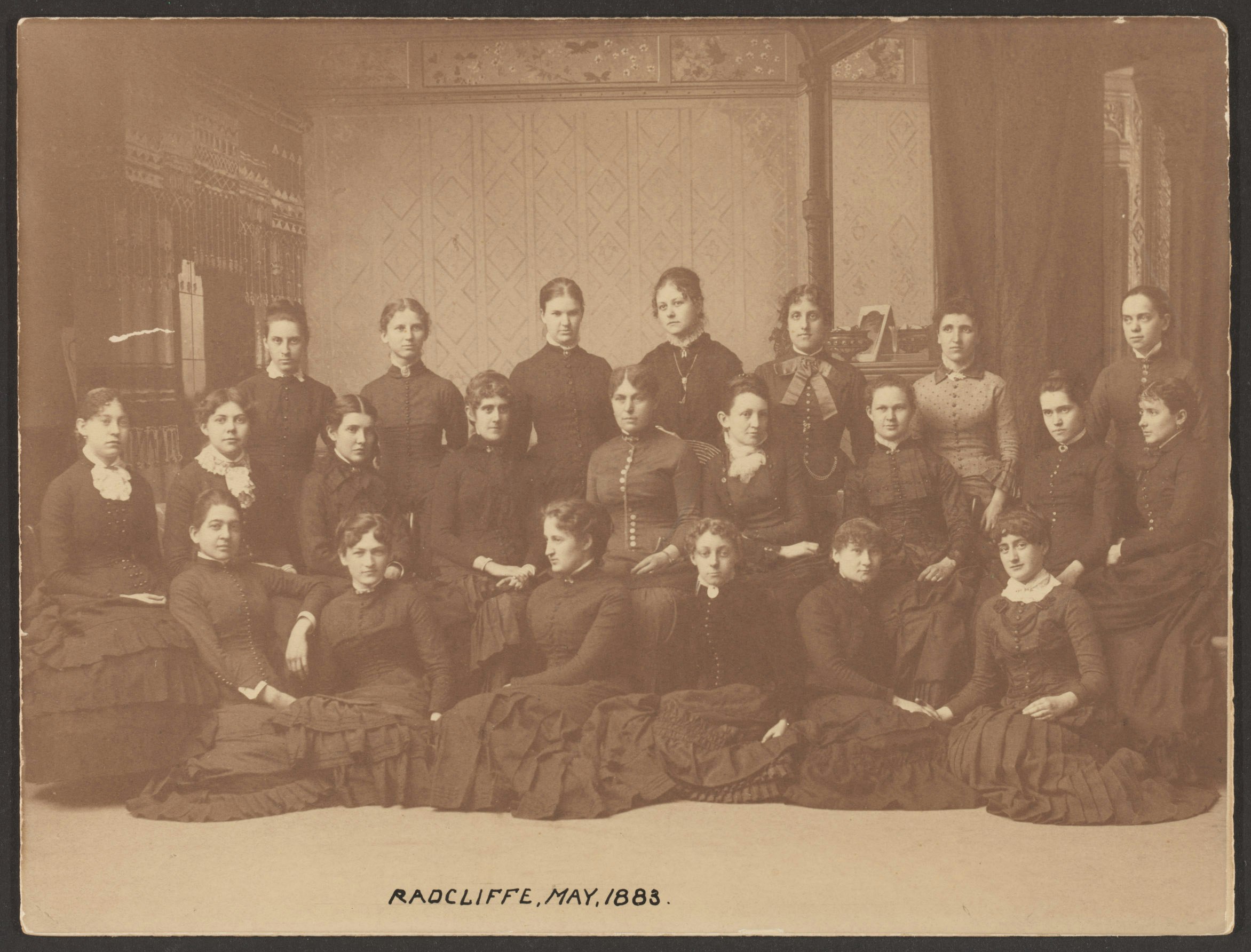

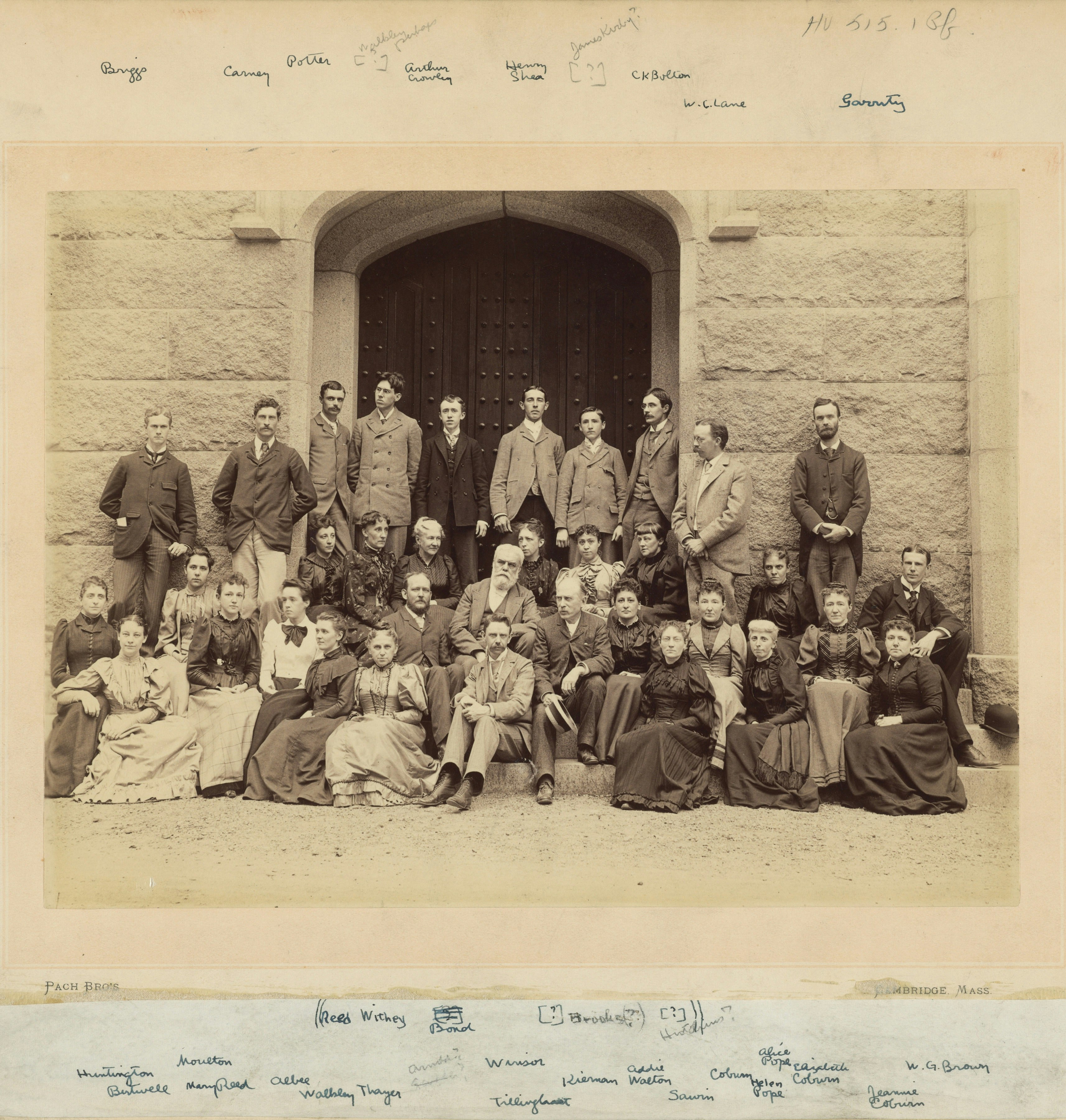

The Radcliffe College Archives at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America are a uniquely valuable resource for the study of women in higher education, the Harvard-Radcliffe relationship, and the lives of the many remarkable women affiliated with Radcliffe College. The archives chronicle Radcliffe College from its beginning as the Harvard Annex in 1879 through its transition to the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study in 1999. The Library's resources about Radcliffe College were used to create this exploration of the complicated story of women at Harvard University, and an evolution toward equality.

Leading Change

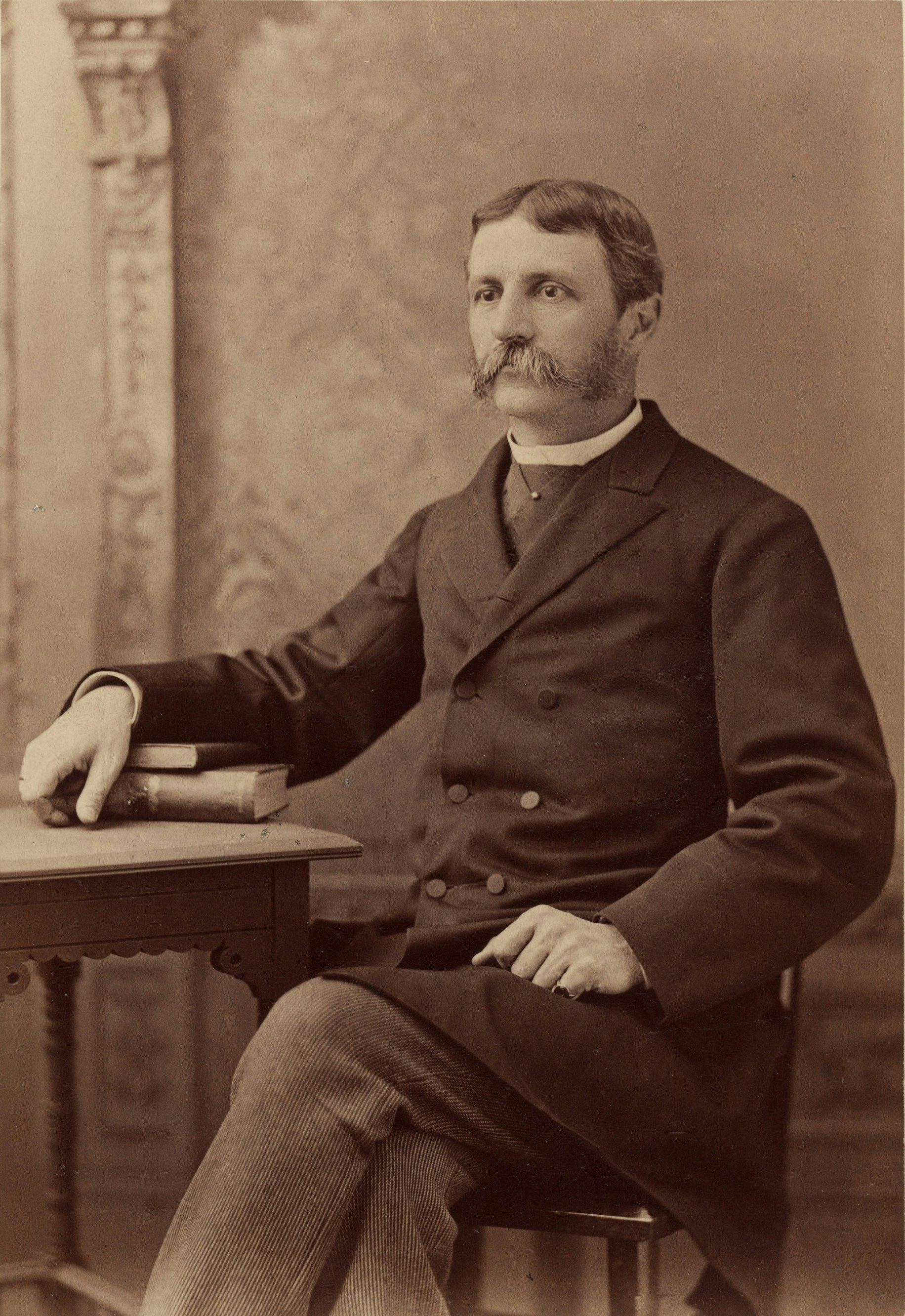

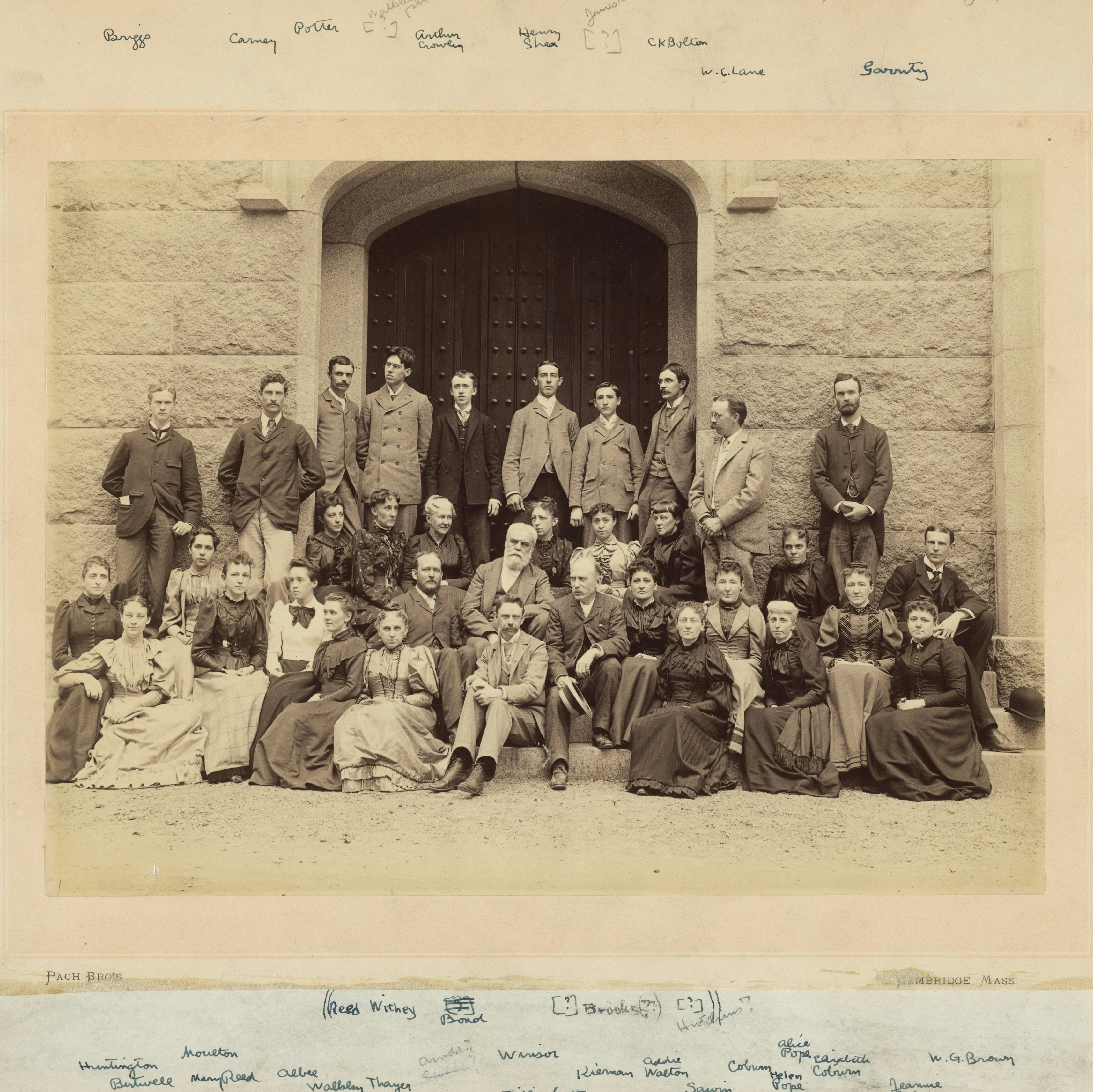

- Arthur Gilman was a proponent of women’s education, both as a founder of the Gilman School for Girls in Cambridge and as founding executive secretary and later regent of Radcliffe College. In 1878, Gilman proposed a plan to offer the same courses to women that Harvard offered to male undergraduates—taught by the same faculty members. This plan was approved by Harvard President Charles Eliot, and in January 1879 a committee of “seven lady managers” was appointed to steward this proposition.

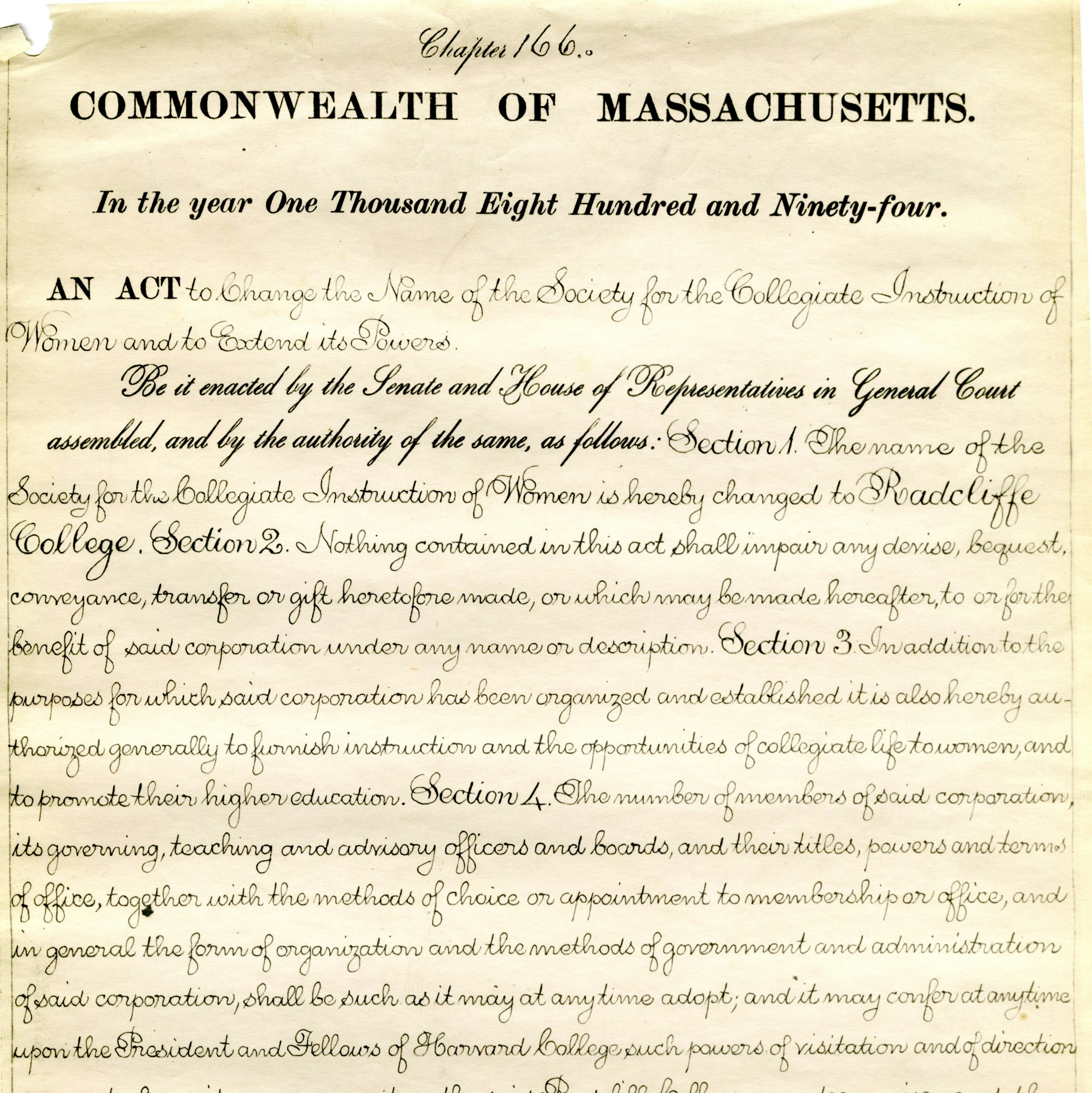

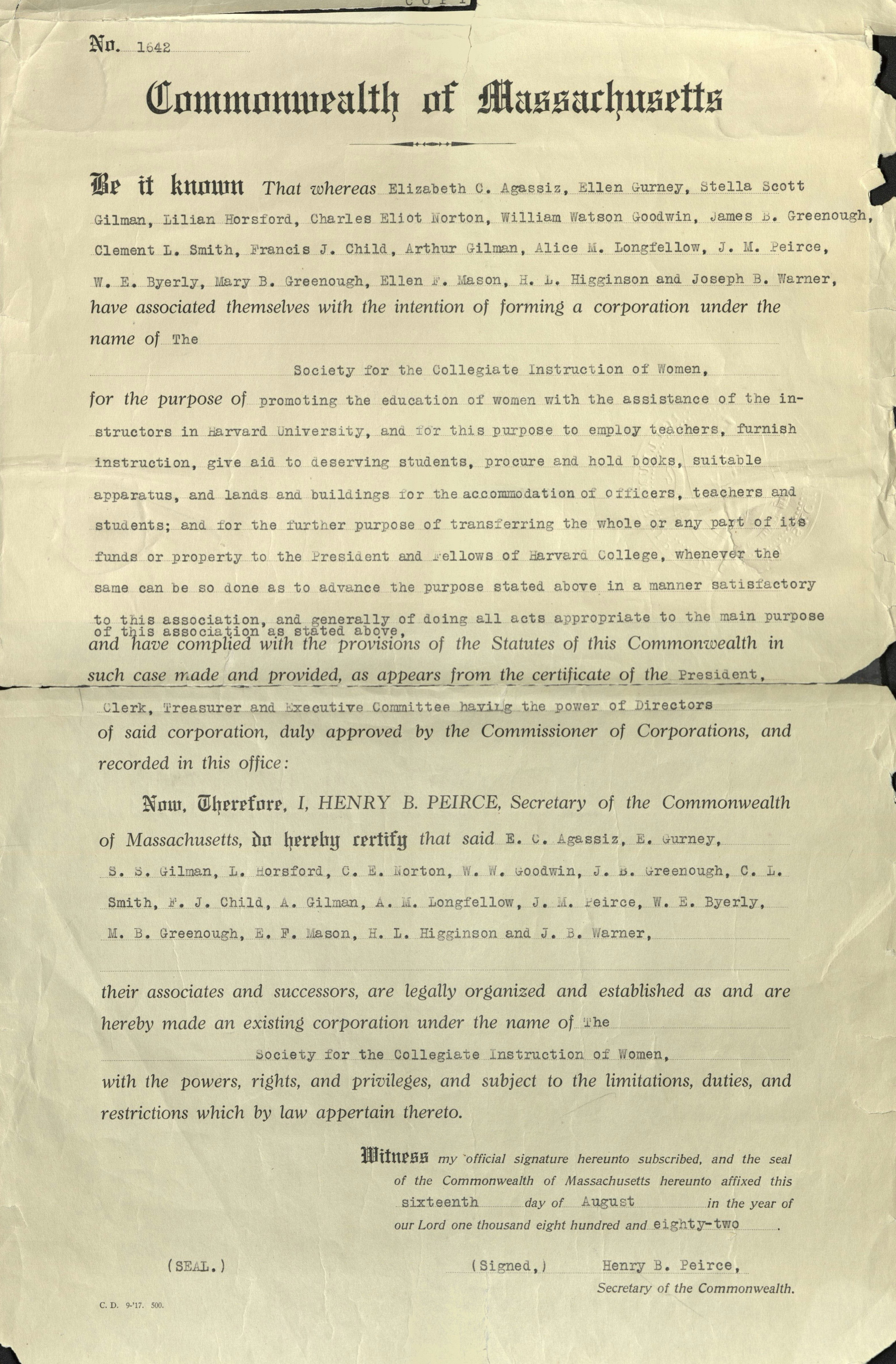

- Among the earliest leaders of the effort to educate women at Harvard, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz served as chair of the “seven lady managers.” Agassiz persuaded 44 professors to teach women in an organization that came to be called the Harvard Annex. In 1882 this enterprise was so successful that it became the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women, and in 1894 it became Radcliffe College. Agassiz was president of Radcliffe College from 1894 to 1899 and served as honorary president until 1903.

- Le Baron Russell Briggs was one of the first Harvard professors who agreed to teach at the newly organized program for the collegiate instruction of women by Harvard professors. He became the second president of Radcliffe College, serving in a part-time capacity while also dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard from 1902 to 1925. During his tenure, the campus grew considerably and yet he remained skeptical of the wisdom of coeducation. While stating in 1922, “I believe that ultimately Radcliffe will become a women’s college in Harvard,” Briggs indicated that he preferred “a friendly plan of dependence and interdependence with no thought of undergraduate coeducation.”

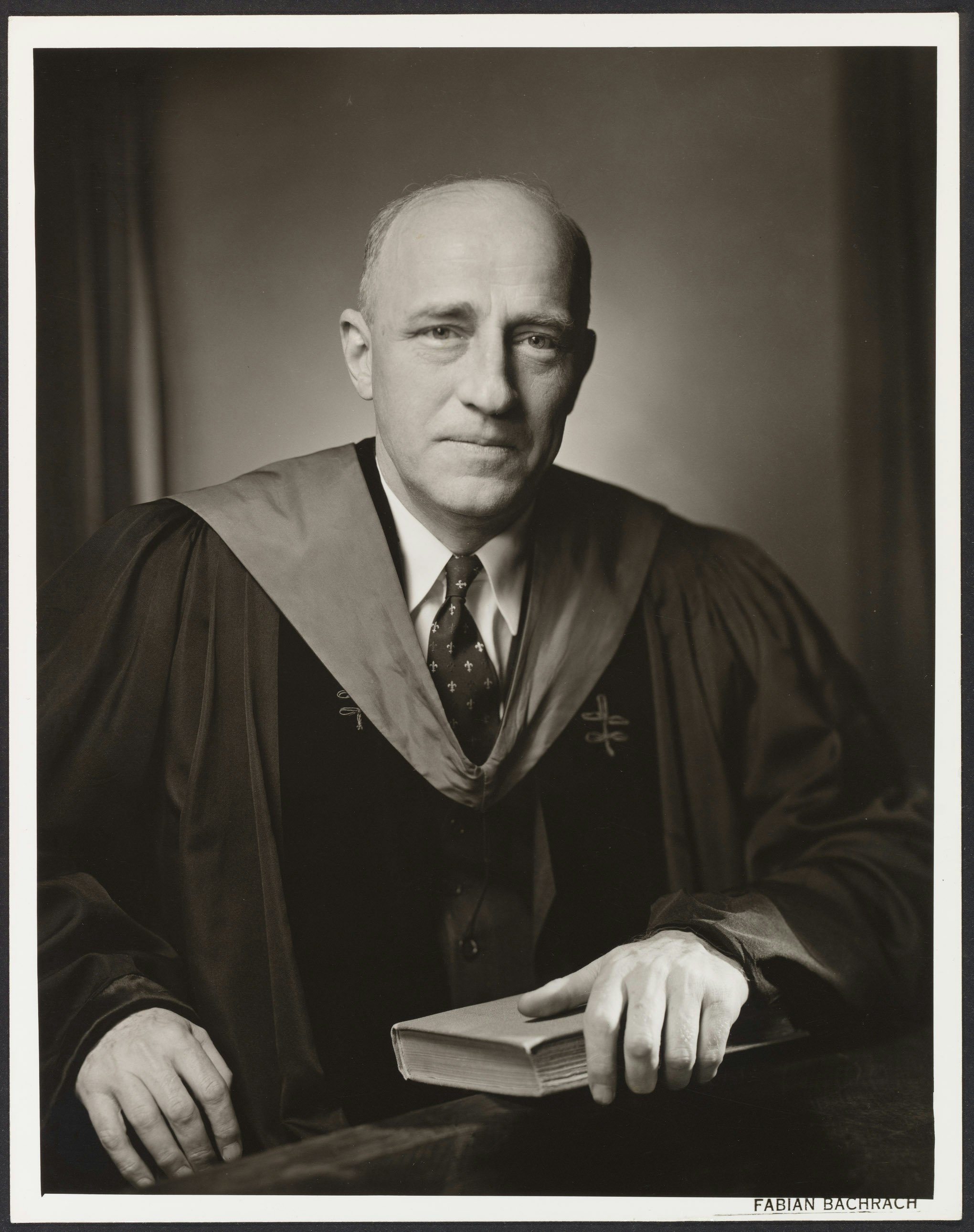

- As President of Radcliffe College in 1943, Wilbur Kitchener Jordan implemented the Radcliffe-Harvard agreement that opened the door to joint instruction of Radcliffe and Harvard students. He participated in the Committee for the Higher Education of Women (1944–1945), which established a general education curriculum for Harvard and Radcliffe. Jordan accepted the Maud Wood Park collection of suffrage material that became the nucleus of the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America.

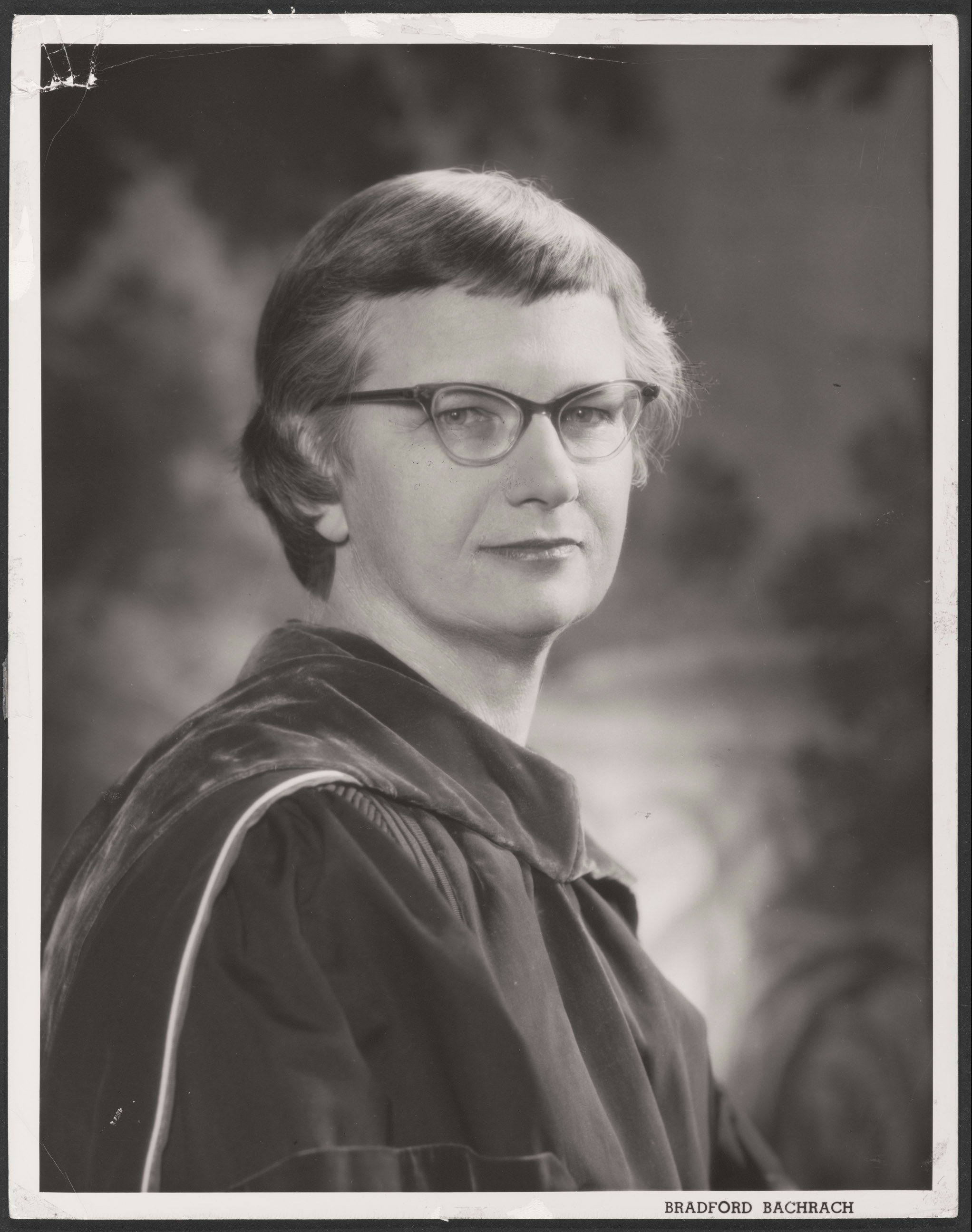

- Known to the Radcliffe community as “Polly,” Mary Ingraham Bunting was president of Radcliffe College from 1960 to 1972. Bunting initiated fellowships for women whose education had been interrupted, allowing them to return to study in all fields, including the arts. This program was known as the Radcliffe Institute. During her presidency, Radcliffe students began receiving the Harvard degree, and the Radcliffe diploma was eliminated. Bunting also implemented the agreement that provided for co-residential houses where male and female students were allowed to live together.

- Drew Gilpin Faust was the founding dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, a position she served from January 2001 to October 2007. Faust led the transformation of Radcliffe from a college into a wide-ranging institute for scholarly and creative enterprise. Drew Gilpin Faust is currently the 28th President of Harvard University.

01 / 06

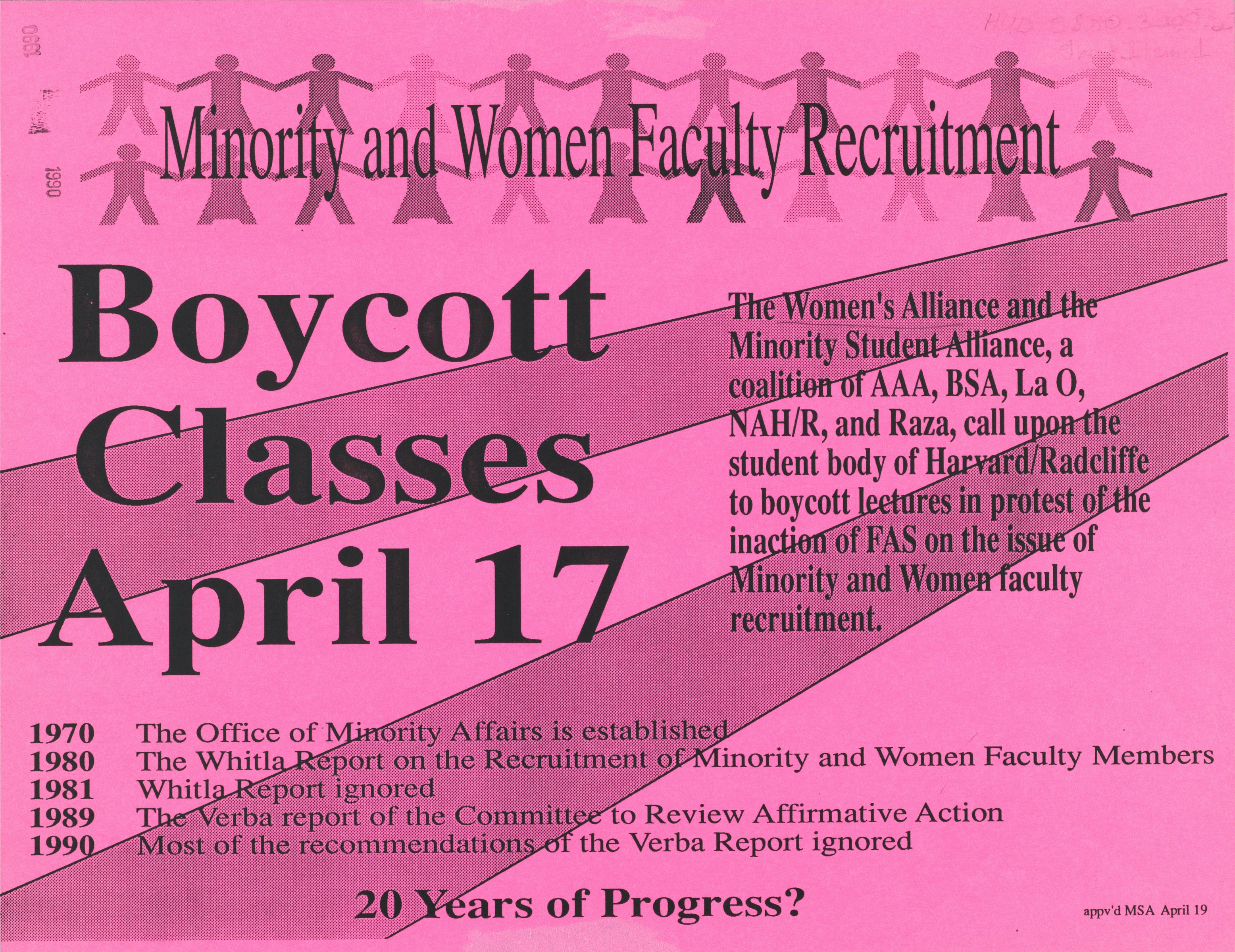

First Among Faculty

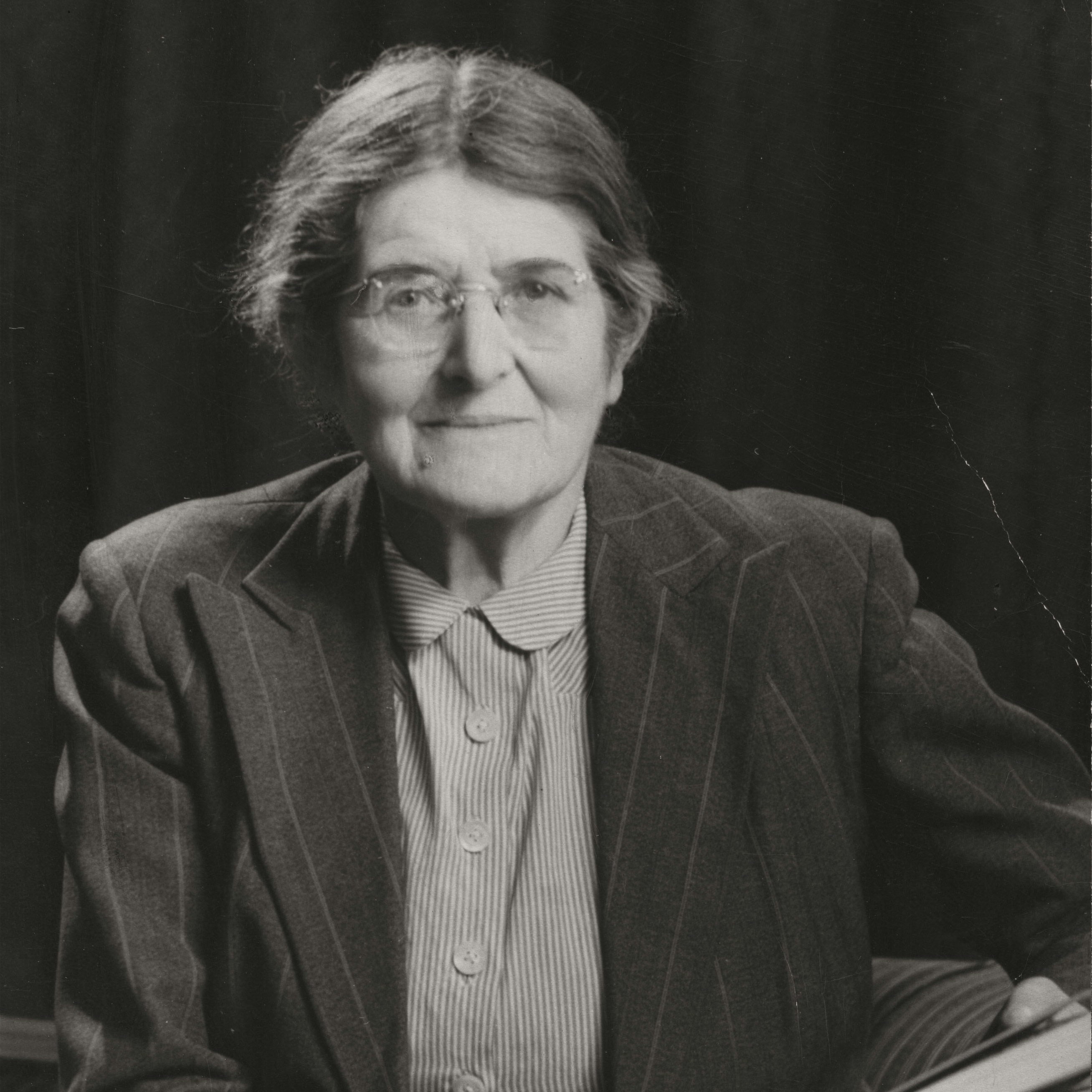

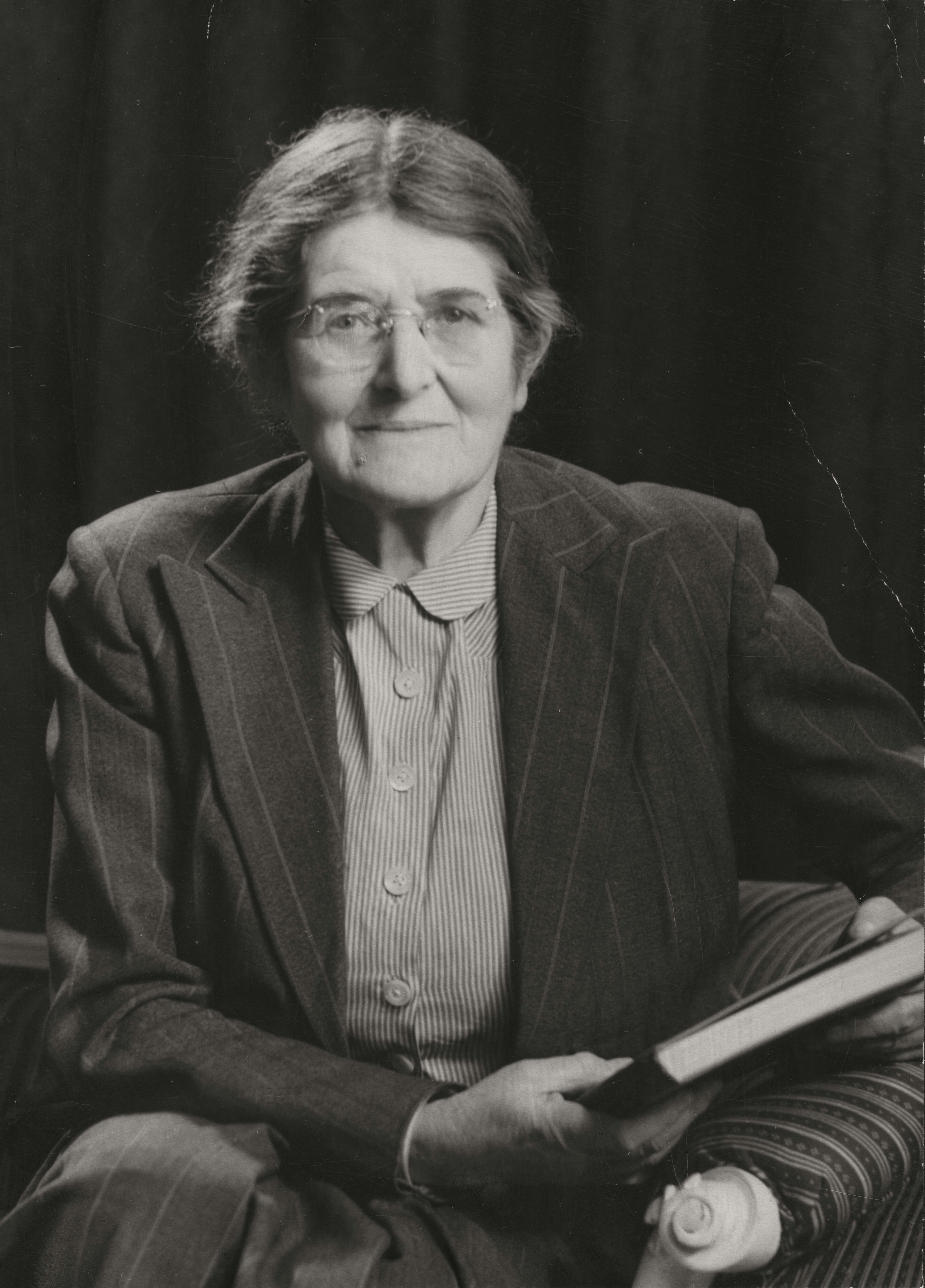

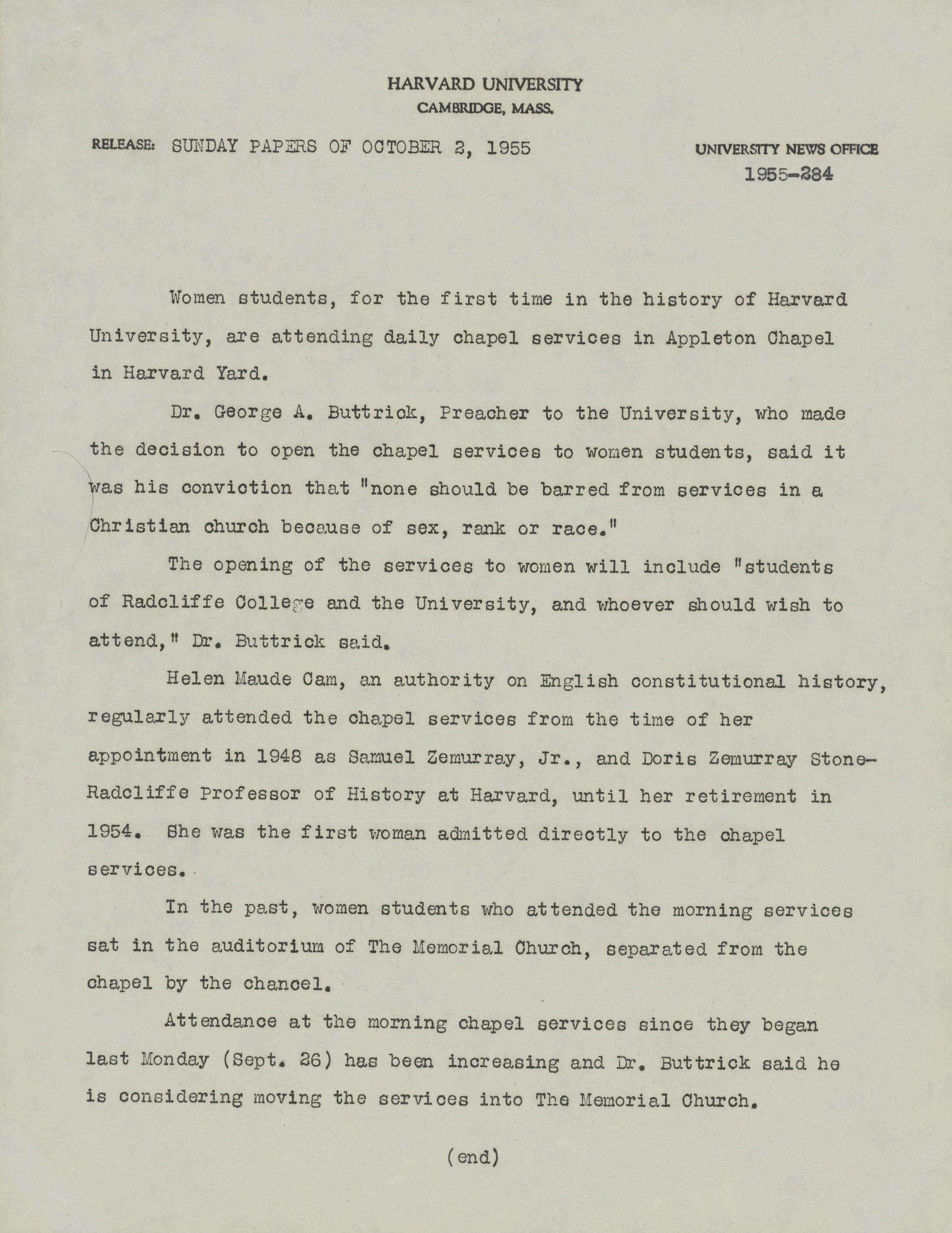

- Without a faculty of its own, Radcliffe students were always taught by Harvard professors. Until the mid-20th century, those professors were all men. In 1948 Helen Maud Cam, a distinguished authority on English constitutional history and fellow of Girton College, University of Cambridge, England, became the first woman tenured at Harvard, thus ending “a 312 year masculine reign.”

- Cam was also the first woman to hold the Samuel Zemurray Jr. and Doris Zemurray Stone-Radcliffe Professorship, created in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences for a distinguished woman scholar.

- The next two women to hold this chair were Cora A. DuBois (professor of anthropology) and Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (professor of astronomy), who was also the first woman tenured from within Harvard.

- The graduate school with the earliest women faculty is the Harvard School of Public Health.

- In 1919 Alice Hamilton became Harvard's first woman professor when she was appointed Assistant Professor of Industrial Medicine, Harvard Medical School (after 1928, Harvard School of Public Health).

- In 1957, after retiring as Chief of the Children’s Bureau, pediatrician Martha May Eliot became Professor of Maternal and Child Health at the Harvard School of Public Health.

01 / 06

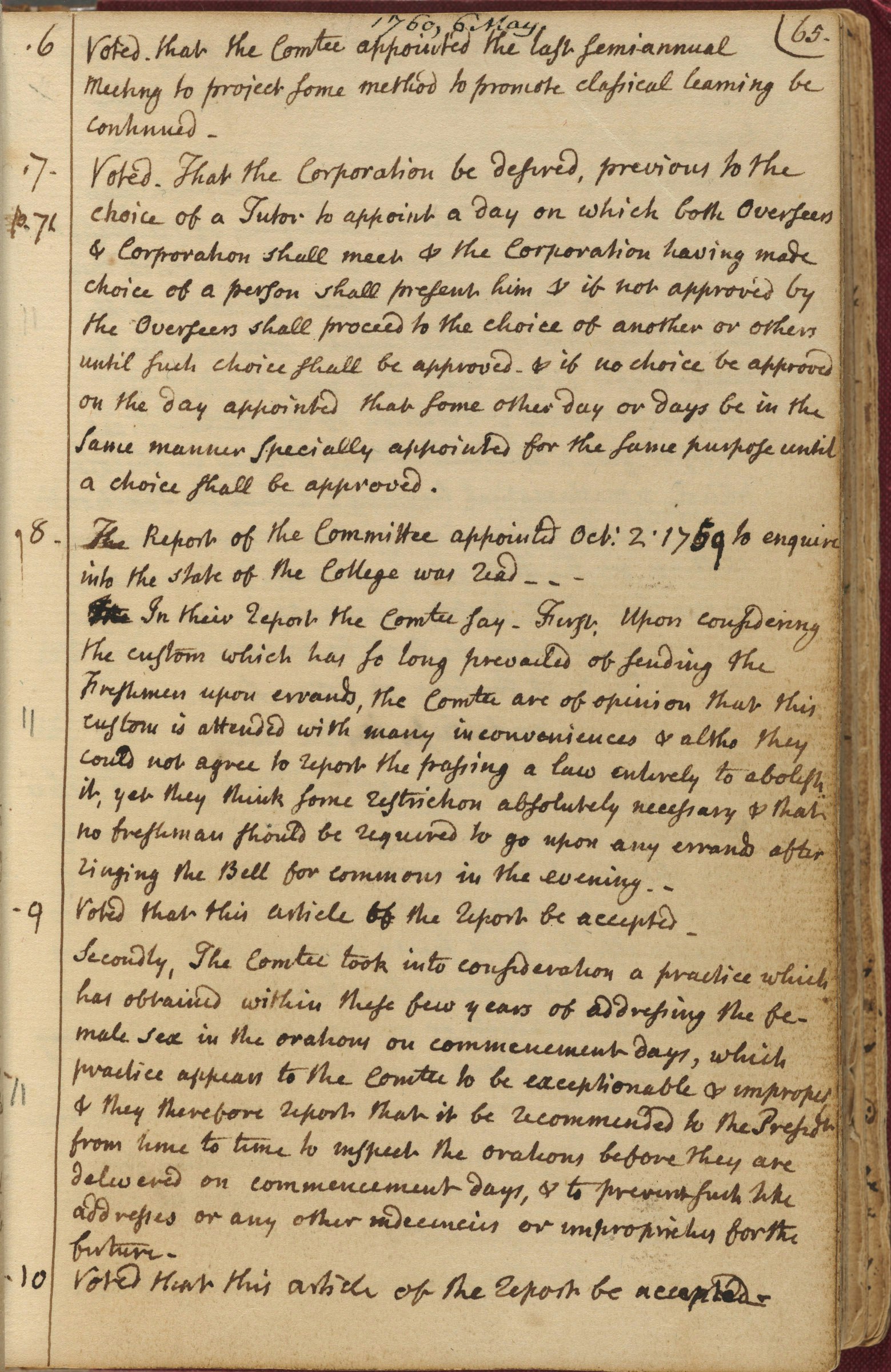

Radcliffe: A Plan, a Society, a College

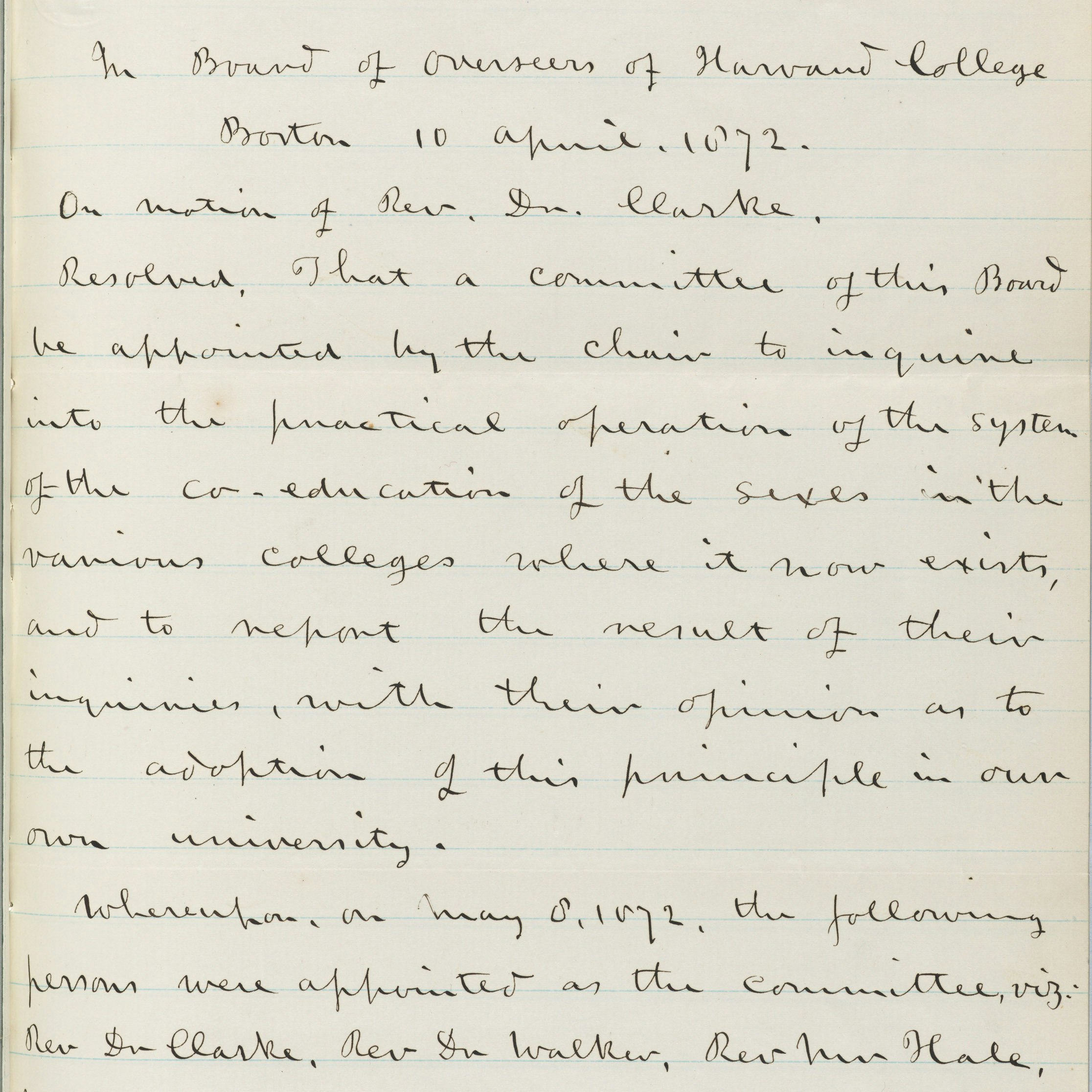

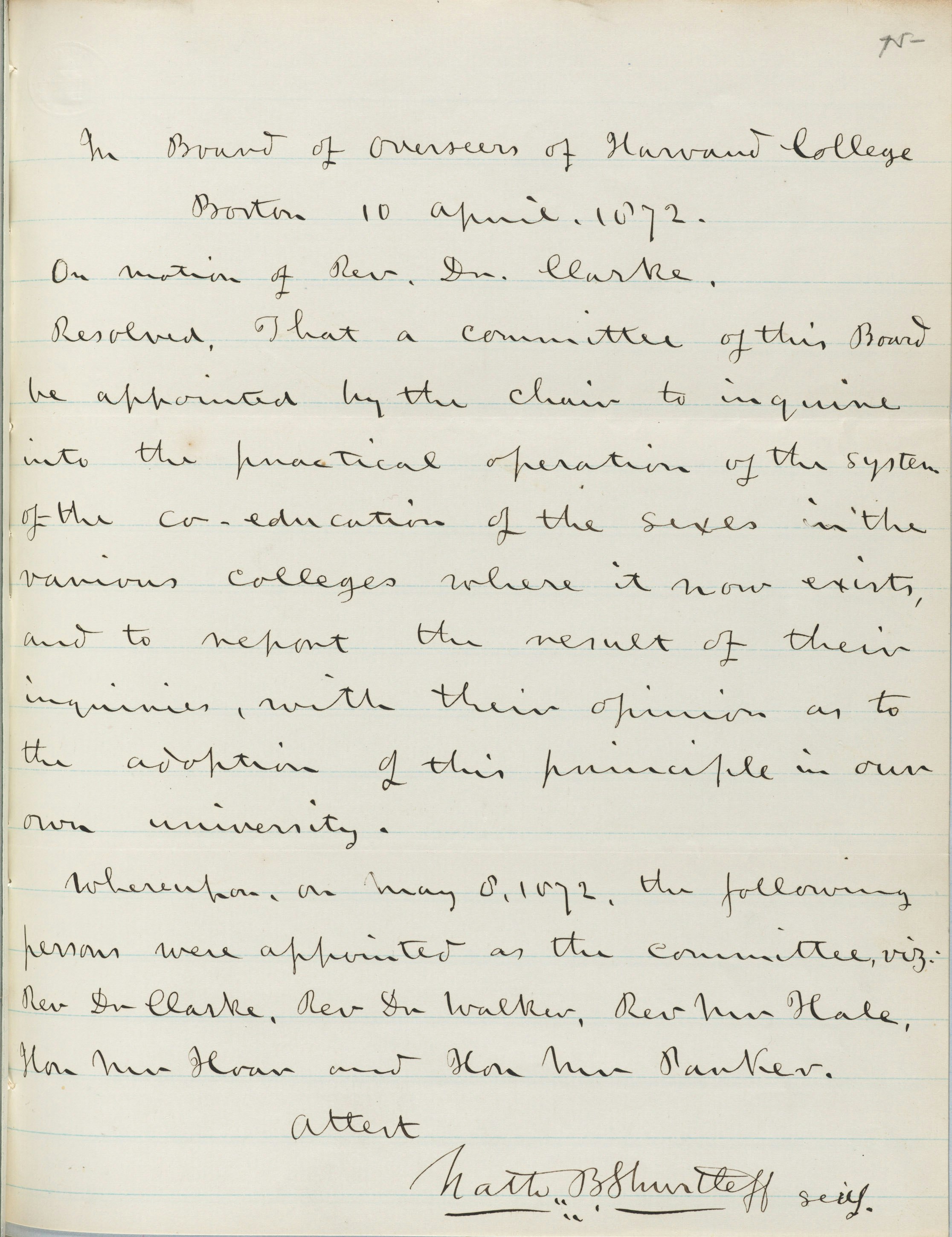

- In the post-Civil War period, momentum grew for Harvard to educate women. In the early 1870s a series of University lectures were opened to women who eagerly enrolled, but the series was short lived. Also at the time, following a request from the Women’s Education Association, Harvard faculty began to create and grade the exams given to women.

- In 1878 three Harvard professors, James B. Greenough, William W. Goodwin, and Francis J. Child, agreed to provide private instruction in Latin, Greek, and English to Abby Leach, a student from Brockton, Massachusetts. The same year Arthur Gilman, founder of the Gilman School, proposed a plan to Greenough whereby a small group of women would be given separate instruction by Harvard professors in the same courses as those offered by Harvard College. Greenough agreed, as he was favorably impressed by his experience teaching Abby Leach.

- To realize his plan, Gilman needed approval from Harvard President Charles Eliot. A committee of “seven lady managers” (Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, Mary H. Cooke, Stella Scott Gilman, Mary B. Greenough, Ellen Hooper Gurney, Alice Mary Longfellow, and Lilian Horsford) was formed to oversee the plan’s launch. With one exception, the members were the wives or daughters of Harvard professors.

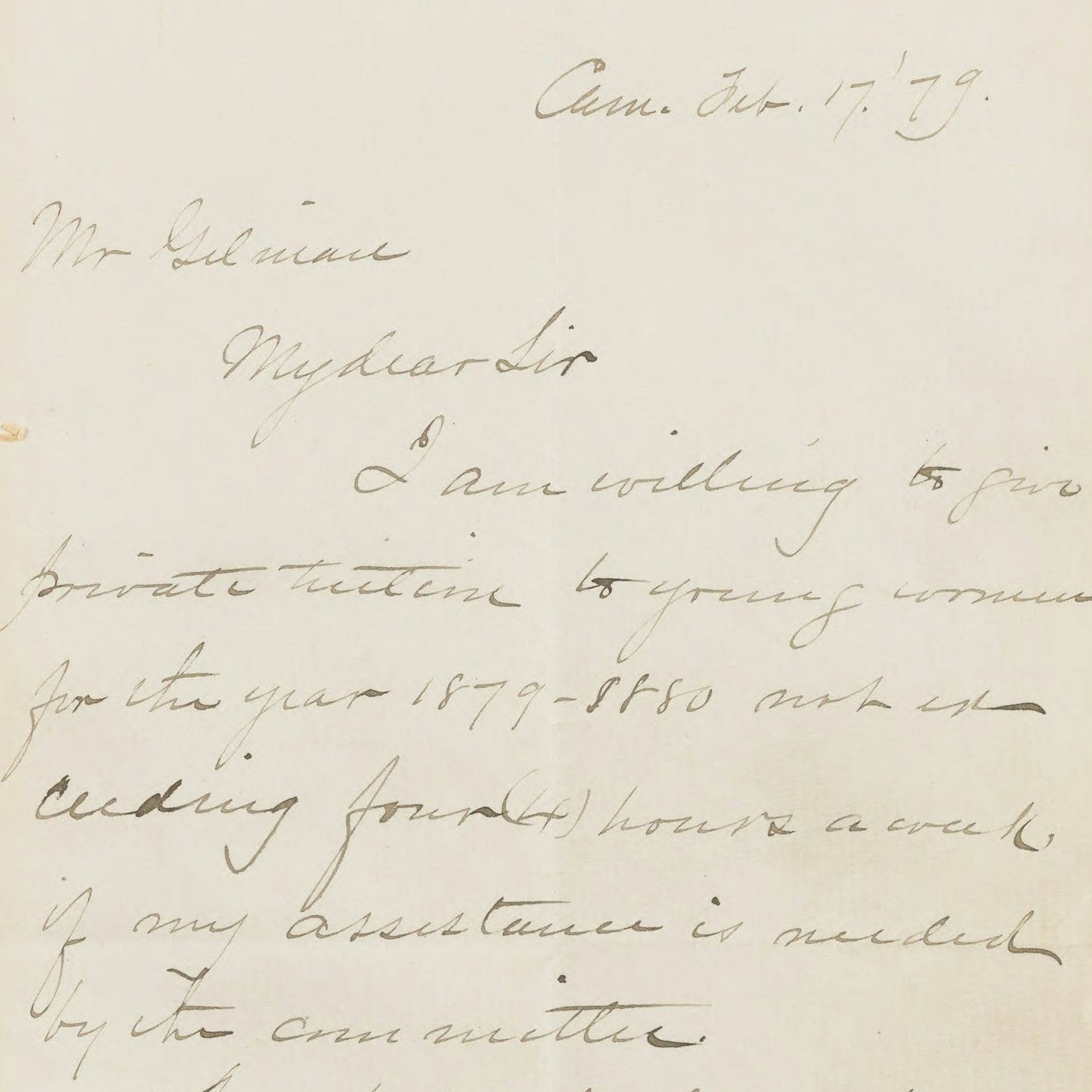

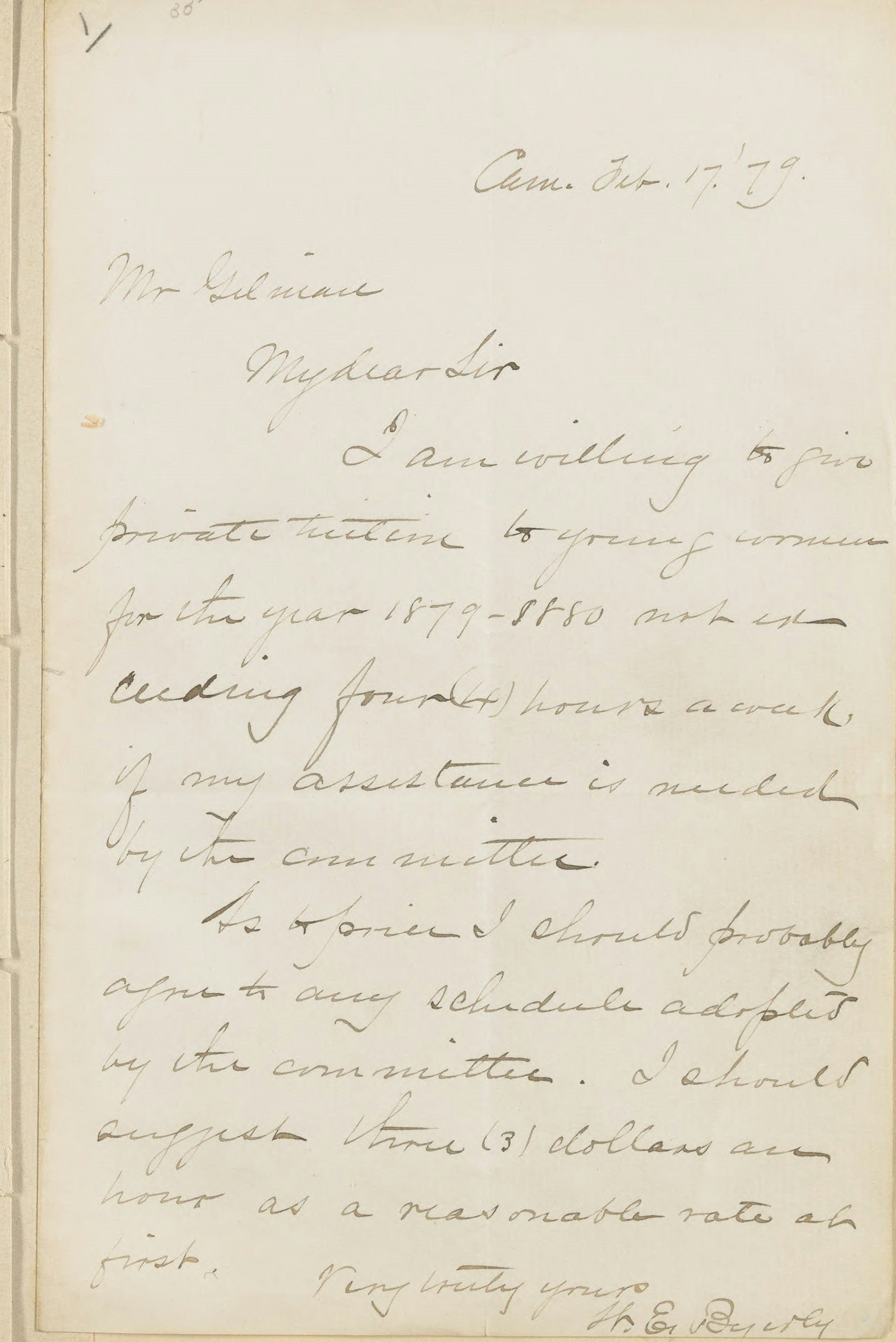

- In February 1879, with President Eliot’s approval, the committee wrote individually to select Harvard faculty, asking whether they would be willing to teach; the first acceptance came from Professor of Mathematics William Byerly, who would become both a member of the governing board of Radcliffe and chairman of the Academic Board.

- The enterprise was announced as the plan for the “Private Collegiate Instruction for Women” in Cambridge and was soon to become known as the Harvard Annex.

- In 1882 the Annex was incorporated as the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women.

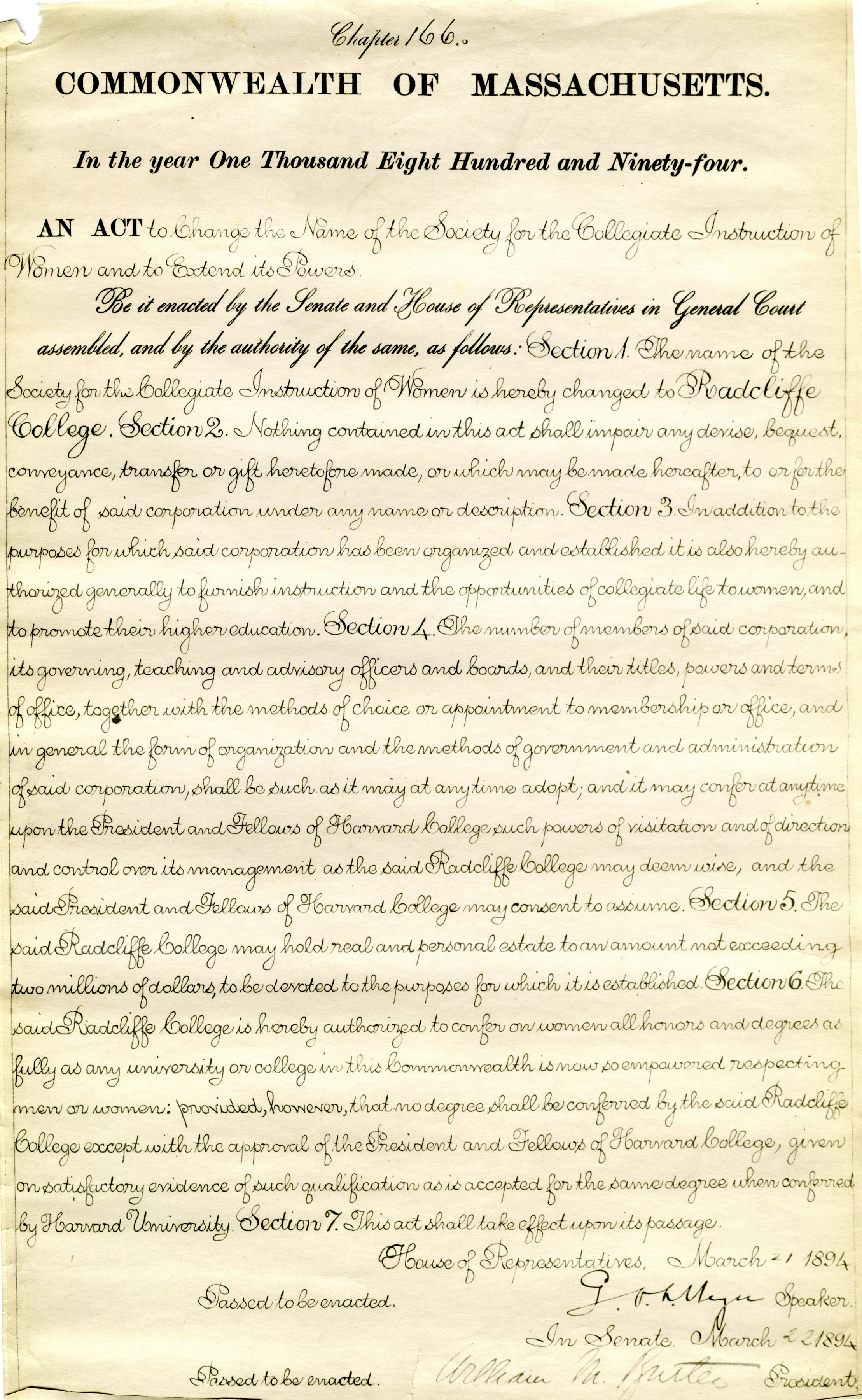

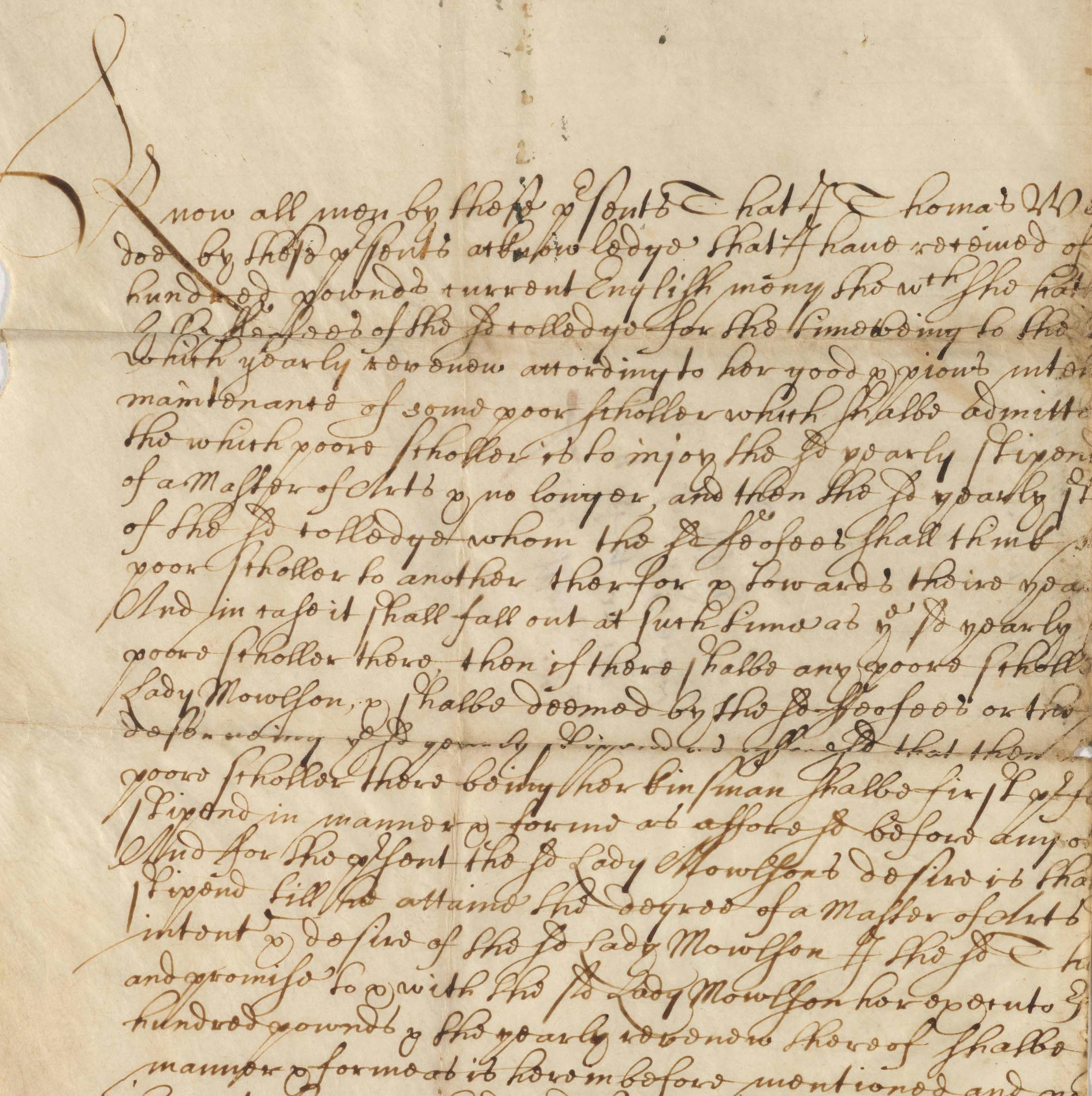

- In 1894 Radcliffe College was chartered and took its name from the Lady Ann Mowlson (née Radcliffe), the first woman to give scholarship money to Harvard.

01 / 07

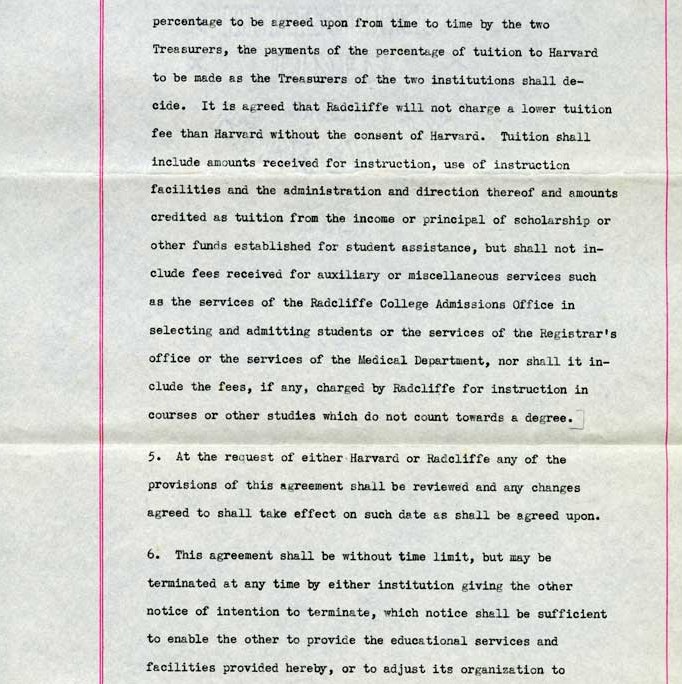

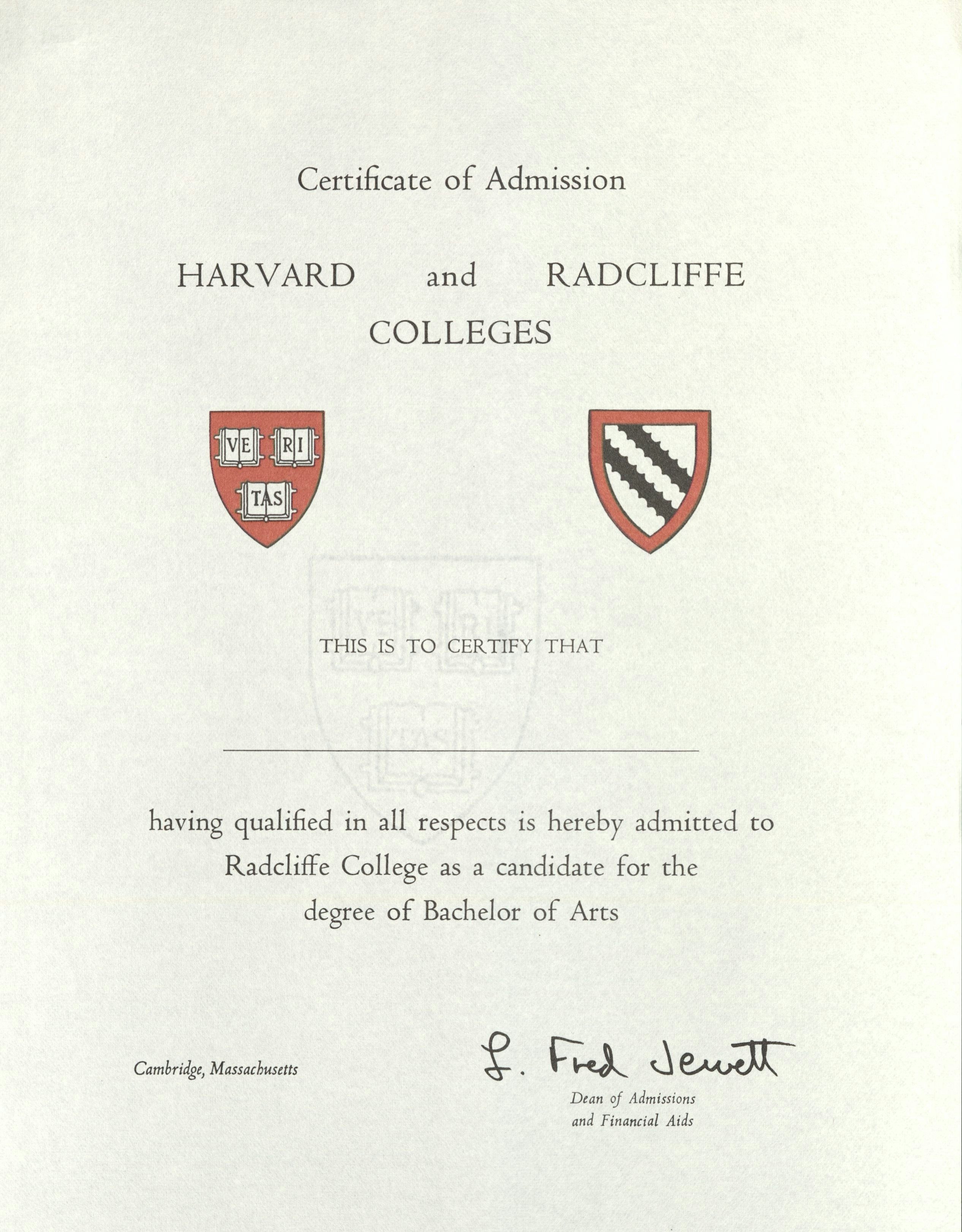

Degrees of Change: A Radcliffe Education Equals a Harvard Education

- Graduates of the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women were awarded certificates signed only by officials of the Society.

- The document certified that the “course of study [was] equivalent in amount and quality to that for which the degree of Bachelor of Arts is conferred in Harvard College and [that the student] has passed in a satisfactory manner examinations on that course, corresponding to the College examinations.

- When Radcliffe College received its charter in 1894, it was “authorized to confer on women all honors and degrees as fully as any university or college in this Commonwealth is now so empowered respecting men or women: provided, however, that no degree shall be conferred by the said Radcliffe College except with the approval of the President and Fellows of Harvard College, given on satisfactory evidence of such qualification as is accepted for the same degree when conferred by Harvard University.”

- Beginning in 1894, the Radcliffe degree was signed by the presidents of Harvard College and Radcliffe College.

- The value of the bachelor’s degree is evident in the Radcliffe College annual reports, where it is noted that some of the students who received earlier certificates exchanged them for an AB degree from Radcliffe.

- In 1963 Radcliffe graduates were awarded Harvard degrees for the first time. Of note, the degree was still signed by both presidents of Harvard and of Radcliffe.

01 / 07

It Is Complicated: The Radcliffe-Harvard Relationship

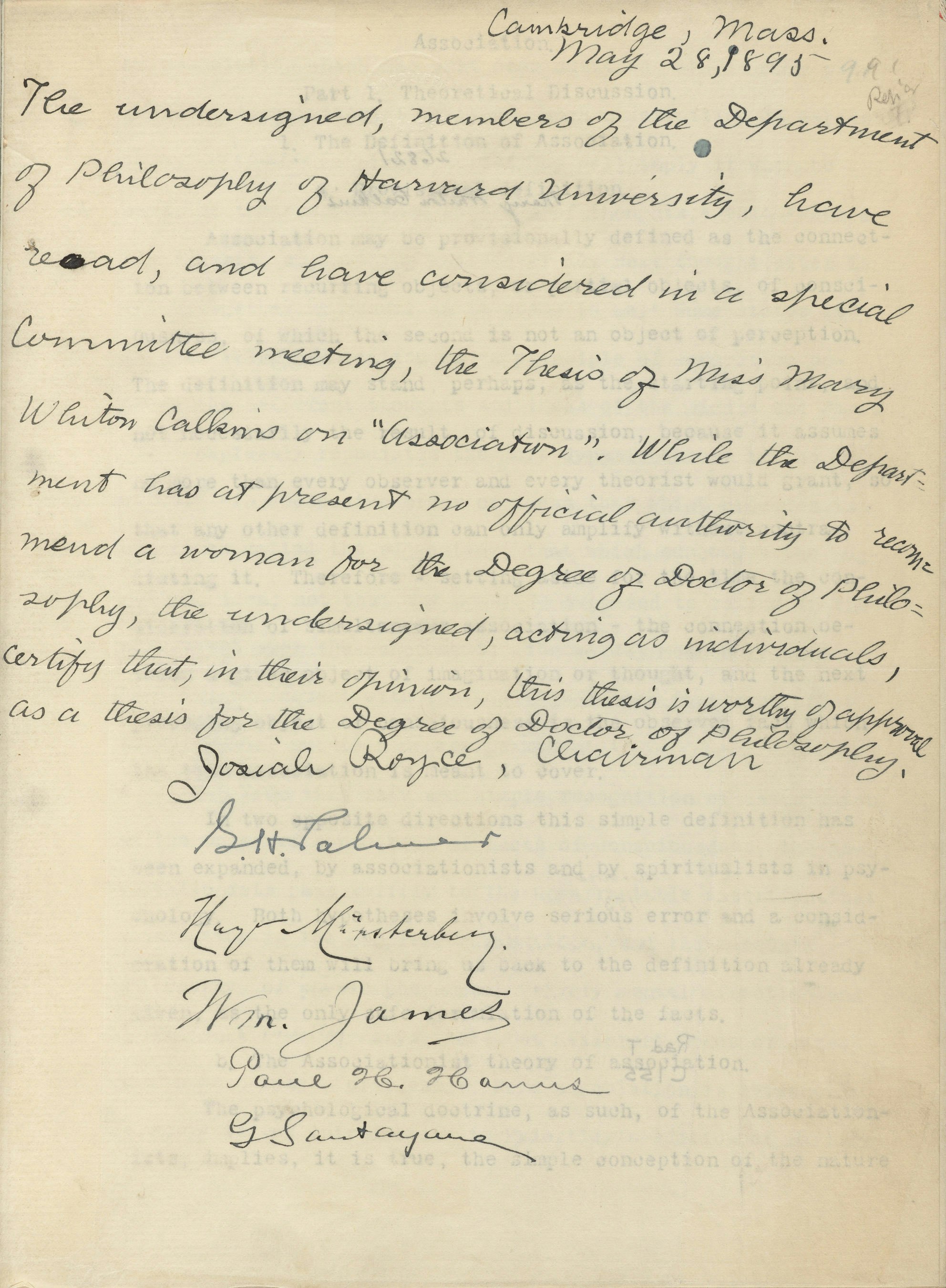

- Mary Whiton Calkins (Smith AB 1885) was the first woman to qualify for the PhD at Harvard. She was invited to study as a guest in the philosophy department and enrolled in courses at Harvard as a Radcliffe student (1885–1886, 1890–1891). Although in 1895 the philosophy department voted that Calkins had satisfied all requirements for the degree, neither Radcliffe nor Harvard awarded doctoral degrees to women at the time. In 1902, when it was decided that Radcliffe rather than Harvard should offer her the PhD, Calkins declined to accept it.

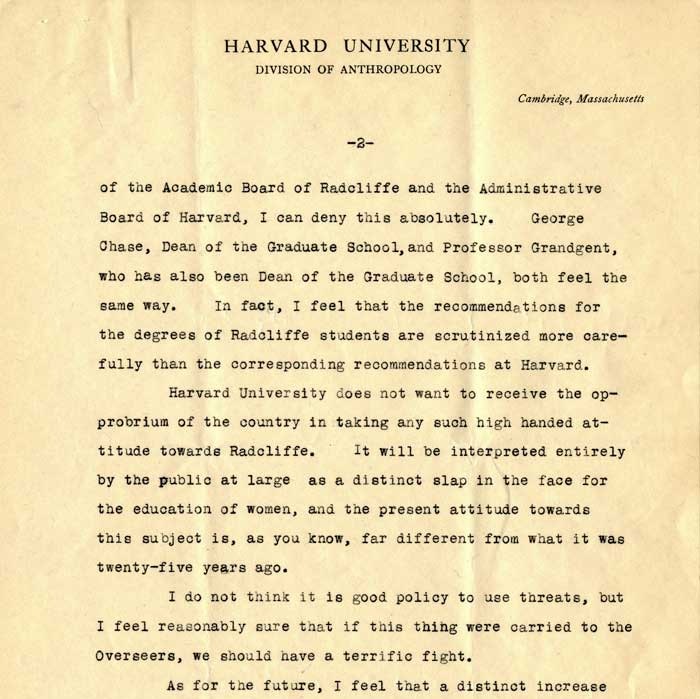

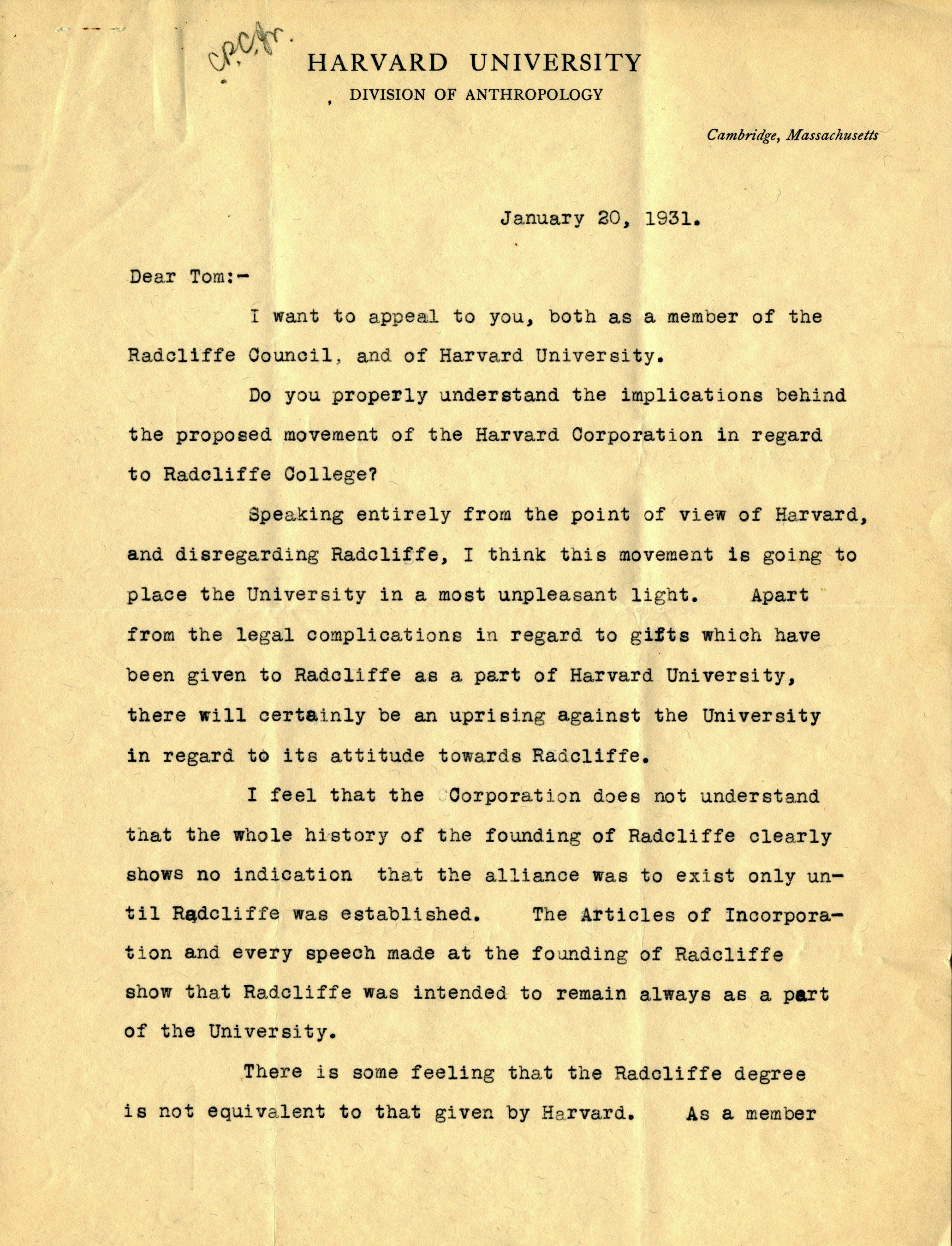

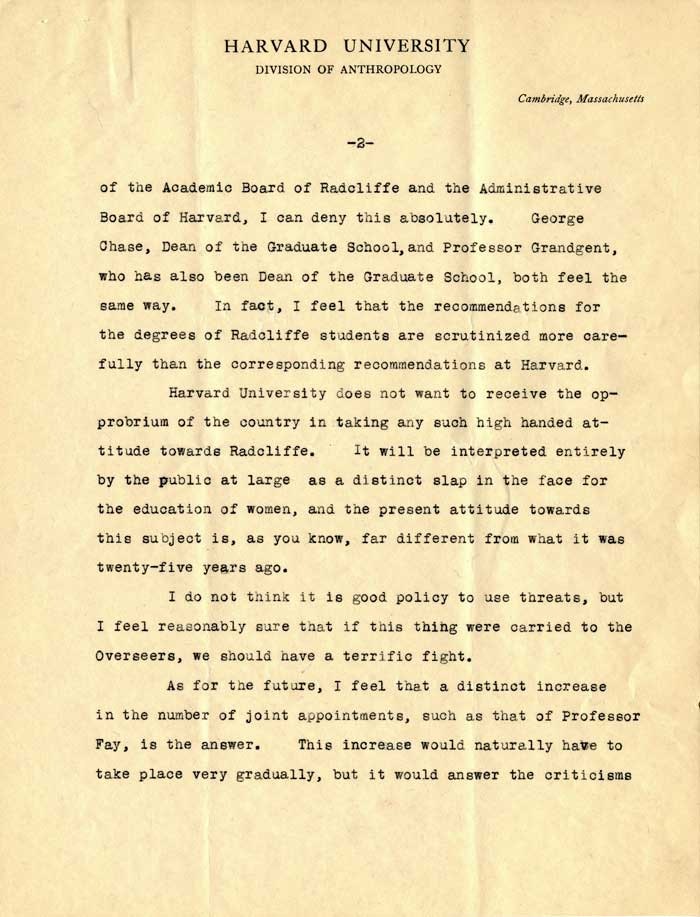

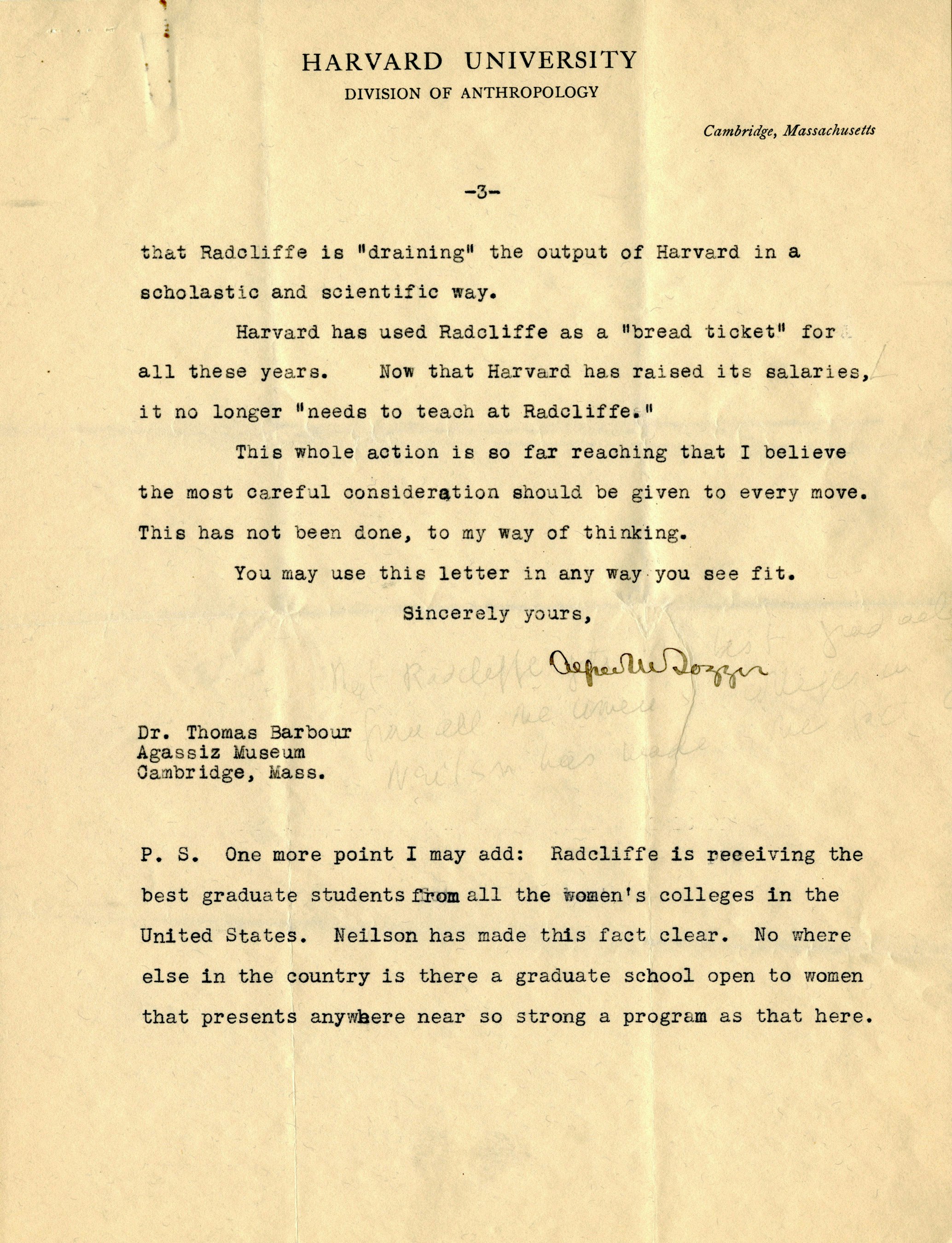

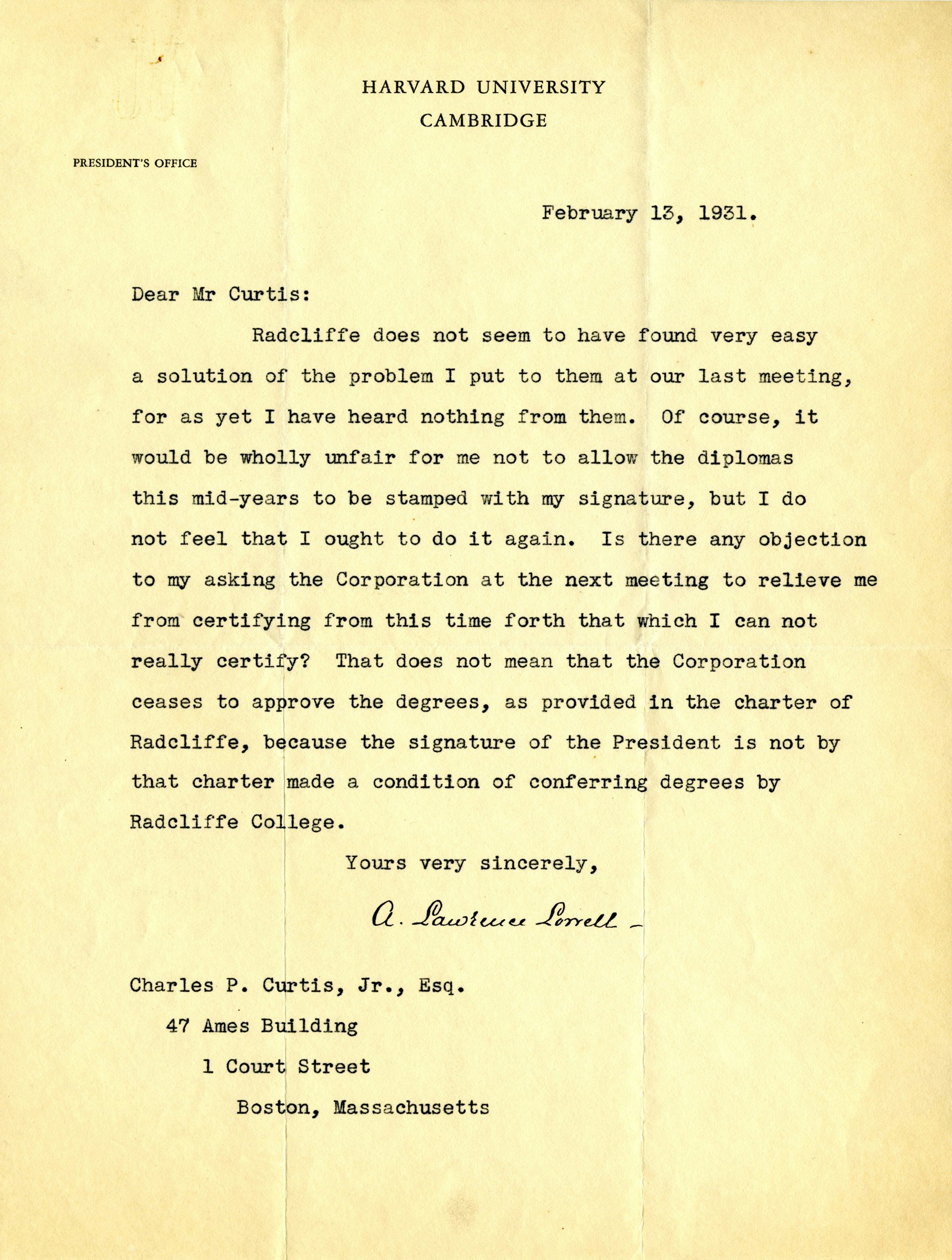

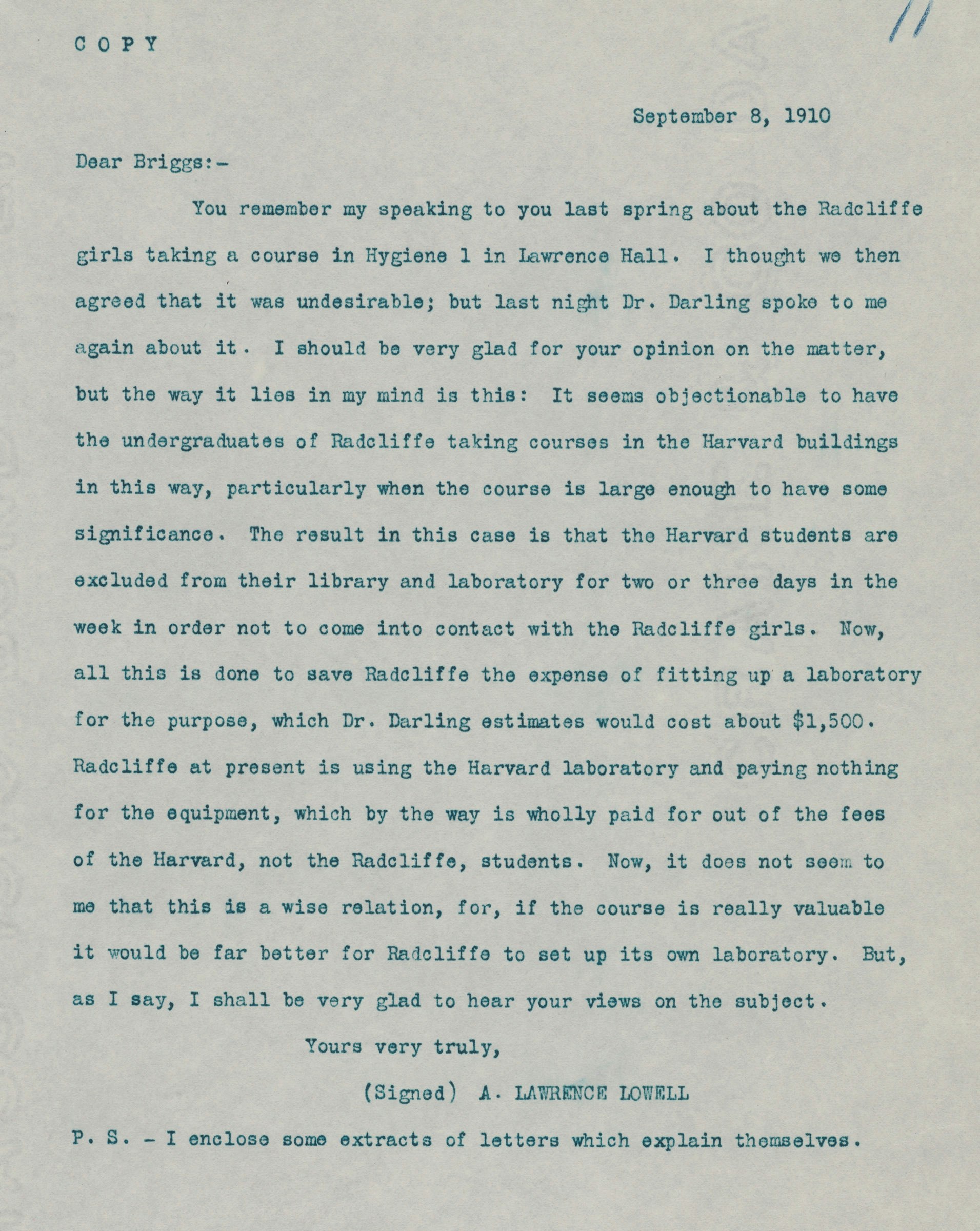

- The early 1930s were a tumultuous time in the Harvard-Radcliffe relationship. Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell considered Radcliffe a burden on Harvard’s resources and intended to sever Radcliffe from Harvard. He began refusing to sign Radcliffe diplomas.

- Radcliffe President Ada Comstock rose to the challenge years later in an address to the Radcliffe Alumnae Association, she reflected: “Mr. Lowell was a resourceful and determined man; and the struggle, for those four years, was pretty nearly incessant and at times gave us all great anxiety. In the long run I think that struggle did us good. It gave us champions and friends whom we otherwise might have lacked.”

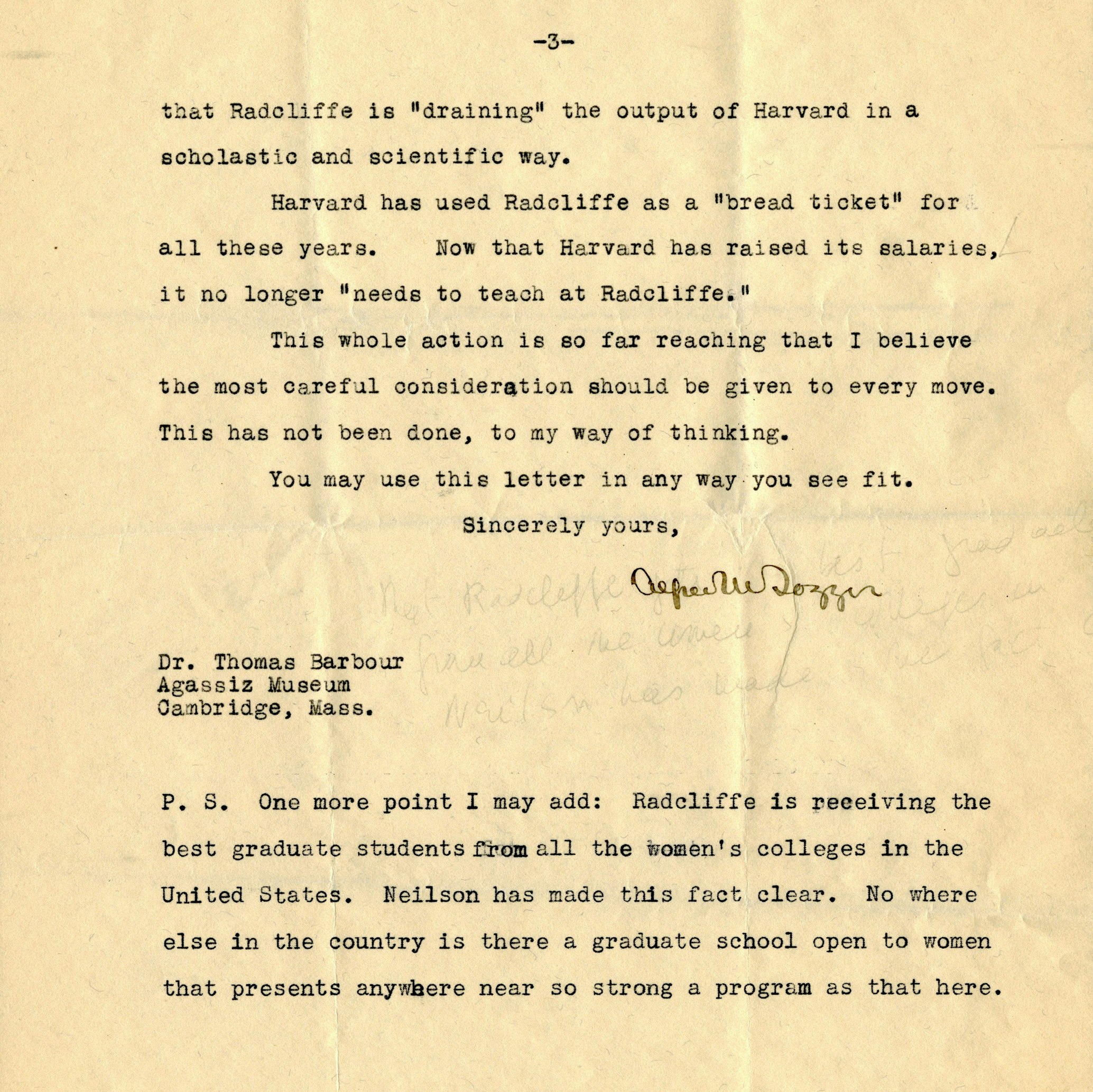

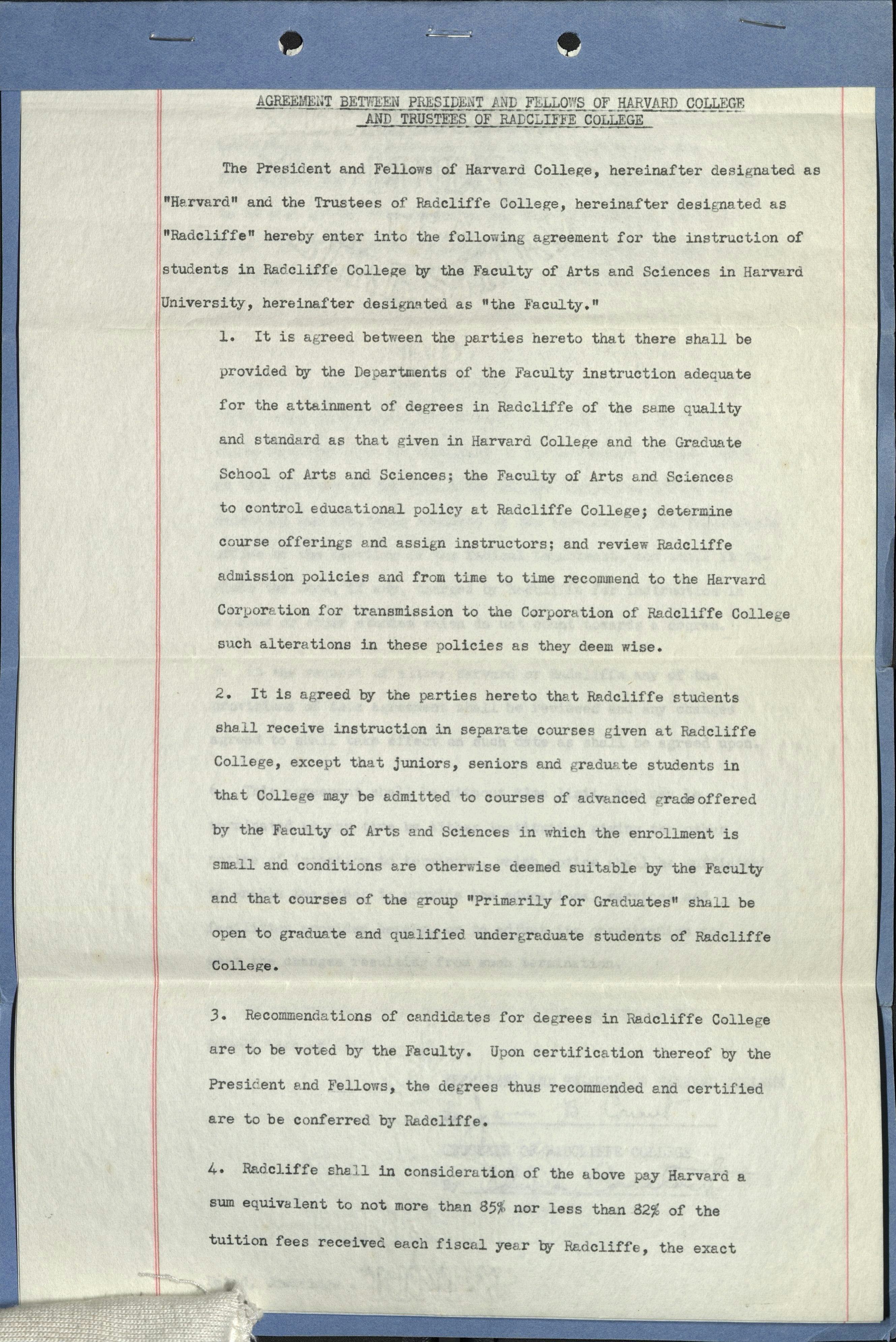

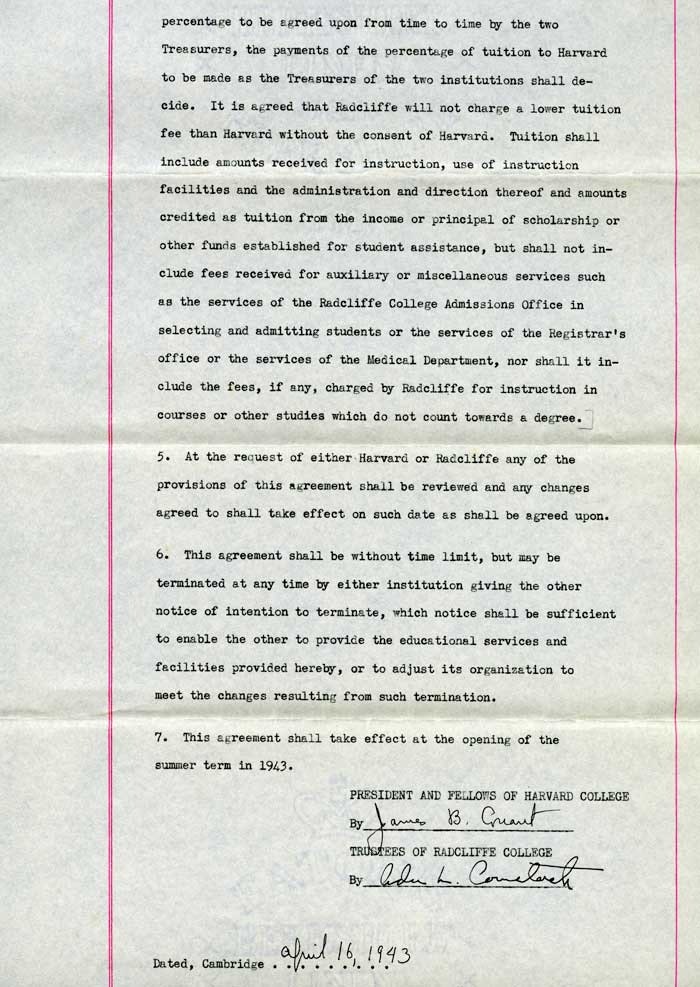

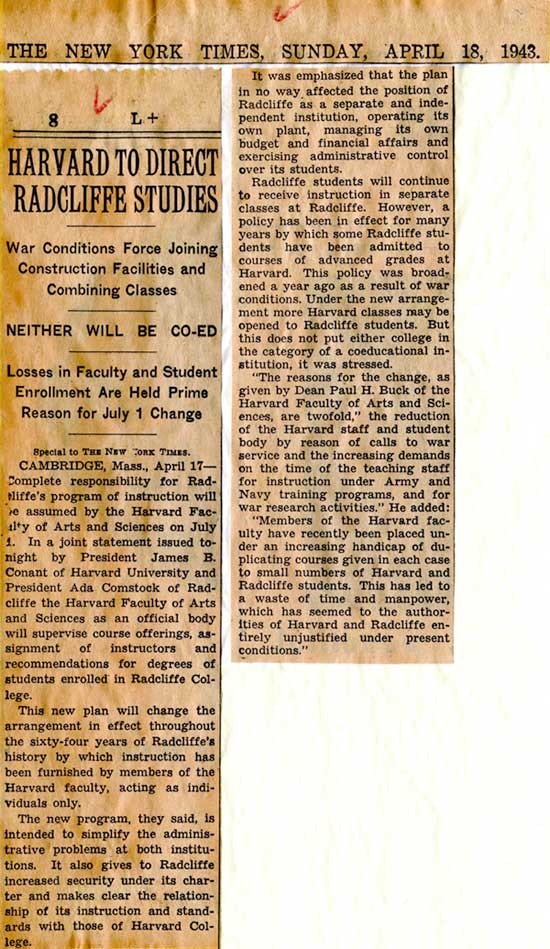

- In 1943, because of the exigencies of war, an agreement was reached for joint instruction. Ada Comstock described this contractual arrangement as “the most significant event since [Radcliffe’s] charter was granted by the legislature in 1894.” Referred to as joint instruction, not coeducation, the agreement provides that Radcliffe undergraduates are allowed in Harvard’s classrooms and that Harvard take full responsibility…..tuition over to Harvard.”

- Brought about by the exigencies of the war, Ada Comstock described this contractual arrangement as “the most significant event since [Radcliffe’s] charter was granted by the legislature in 1894.” Referred to as joint instruction, not coeducation, the agreement provides that Radcliffe undergraduates are allowed in Harvard’s classrooms and that Harvard take full responsibility for educational policy. Radcliffe, for its part, would no longer pay individual professors to teach, but instead turn a major portion of tuition over to Harvard.

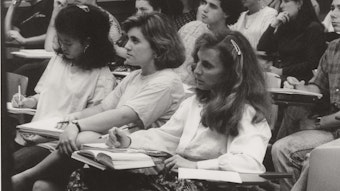

- Achieving an equal access admissions policy for men and women was a highlight of the early 1970s Radcliffe-Harvard relationship. With a then ratio of four men to one woman, in 1972 Harvard allowed “that the number of women admitted would be increased by 150 each year for four years until a ratio of 2.5:1 was reached.” In 1973 Harvard President Derek Bok and Radcliffe President Matina Horner charged a committee chaired by Karl Strauch to study and make recommendations concerning admissions, the needs of coeducation, and administrative arrangements. In 1975 quotas were abolished and the Harvard and Radcliffe admissions offices were merged.

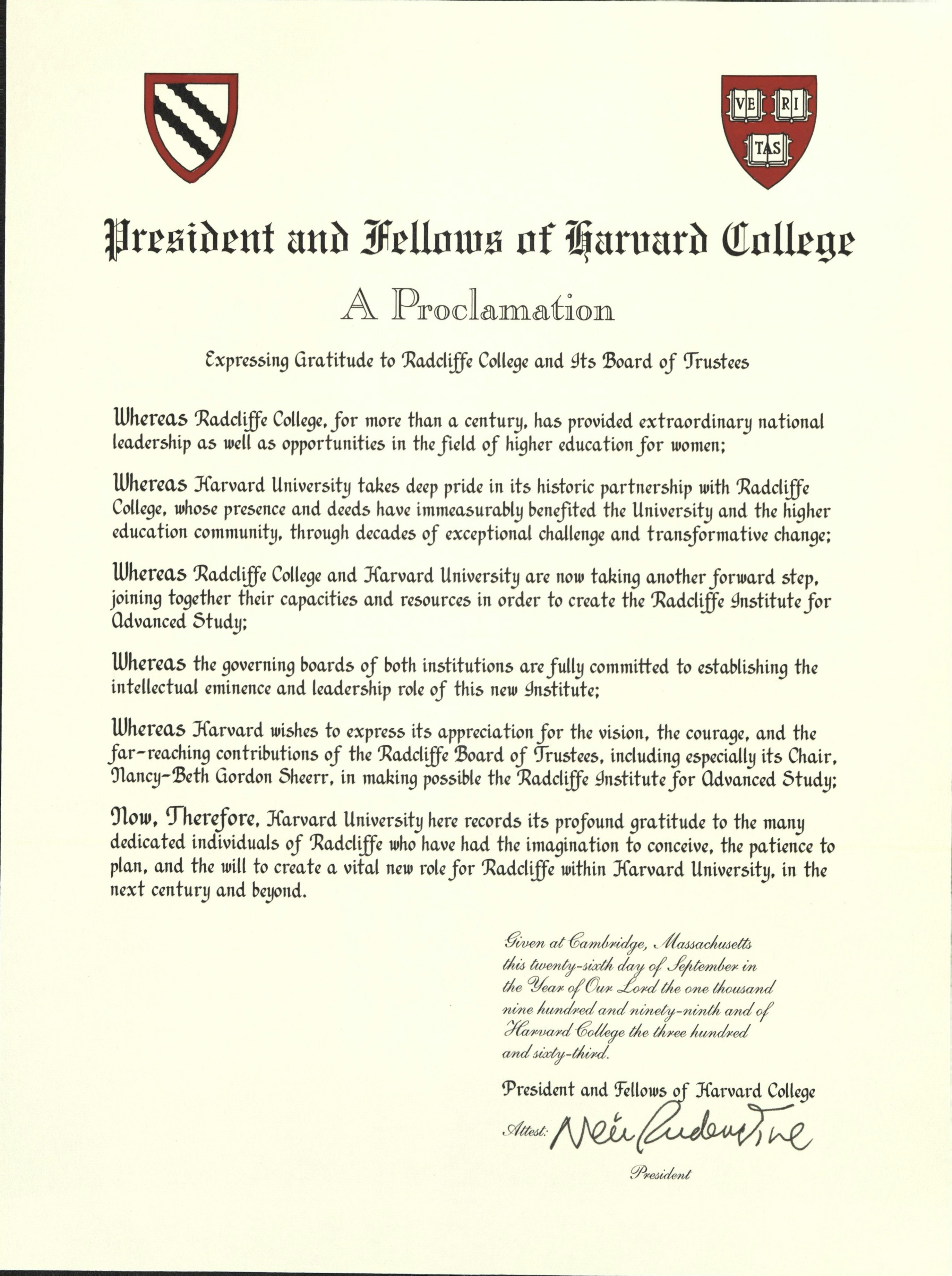

- In 1999 Radcliffe officially merged with Harvard, thereby creating the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Drew Gilpin Faust was the Institute’s first dean.

01 / 12

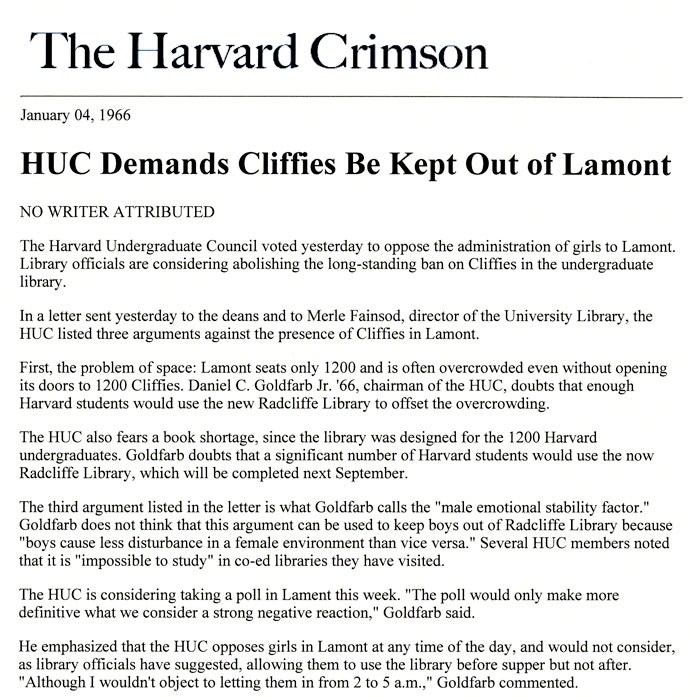

Inclusion/Exclusion

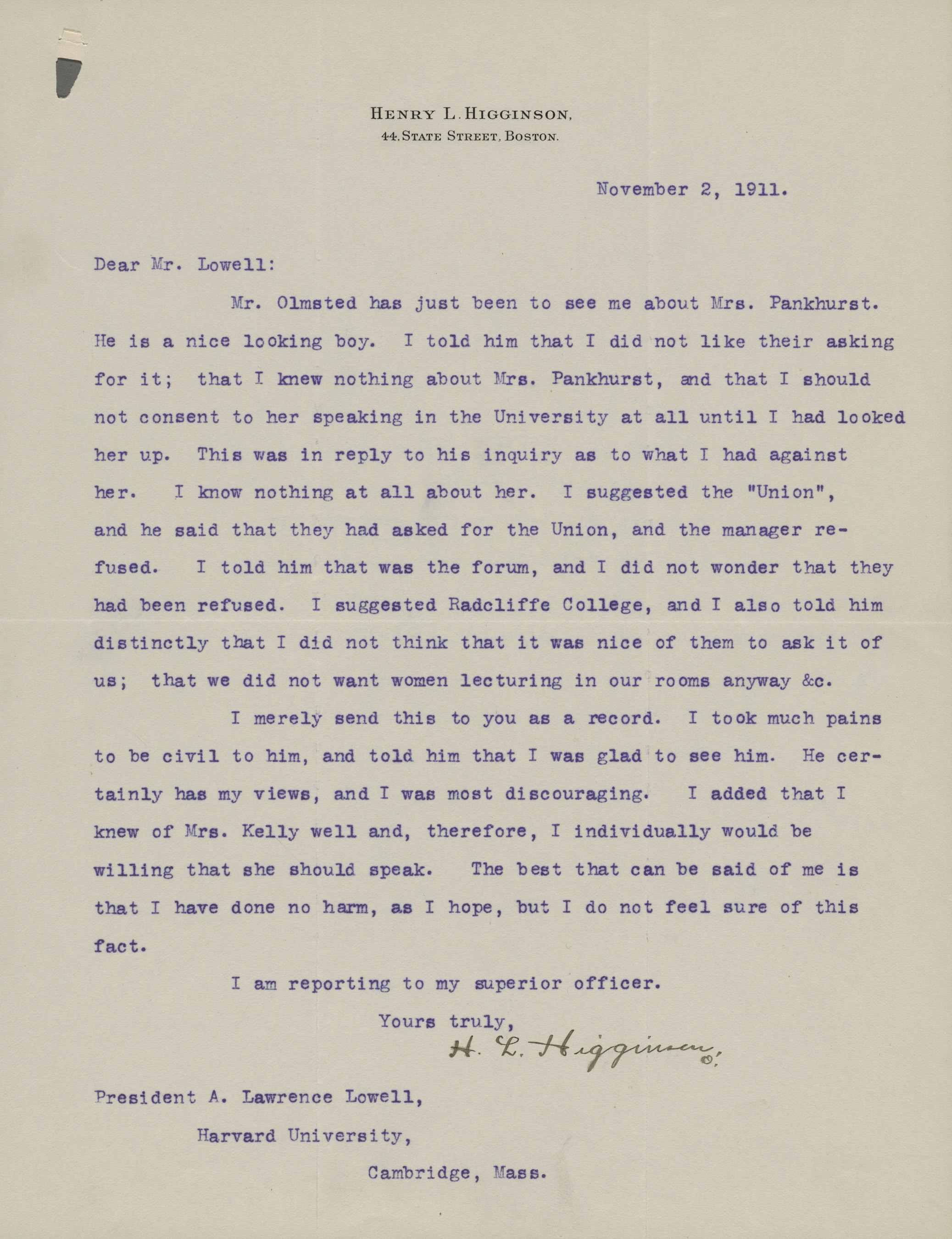

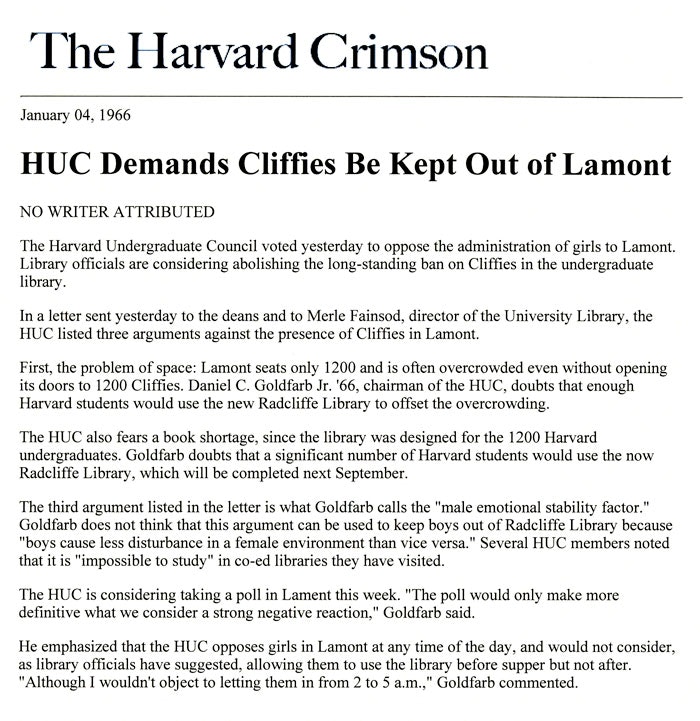

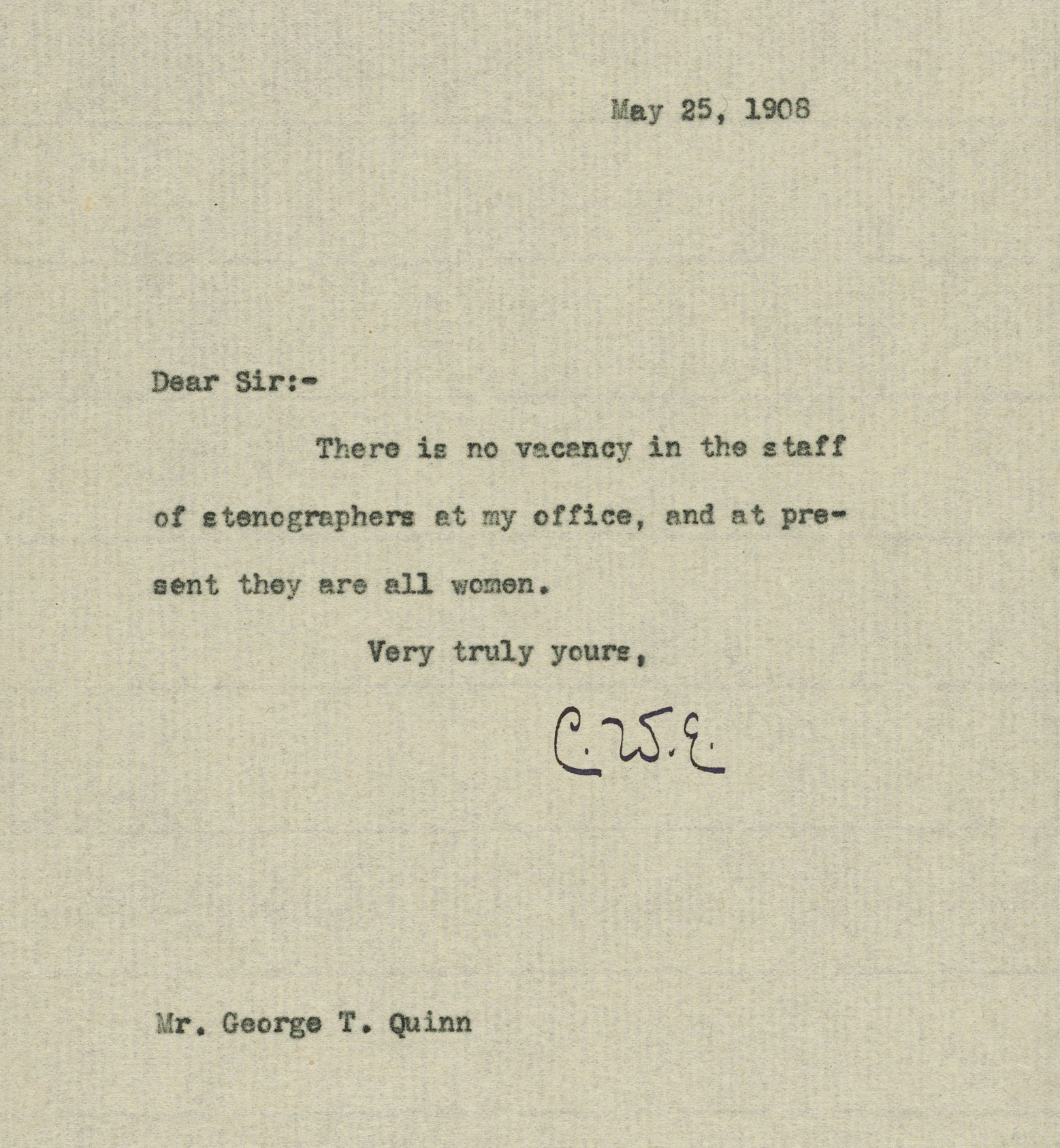

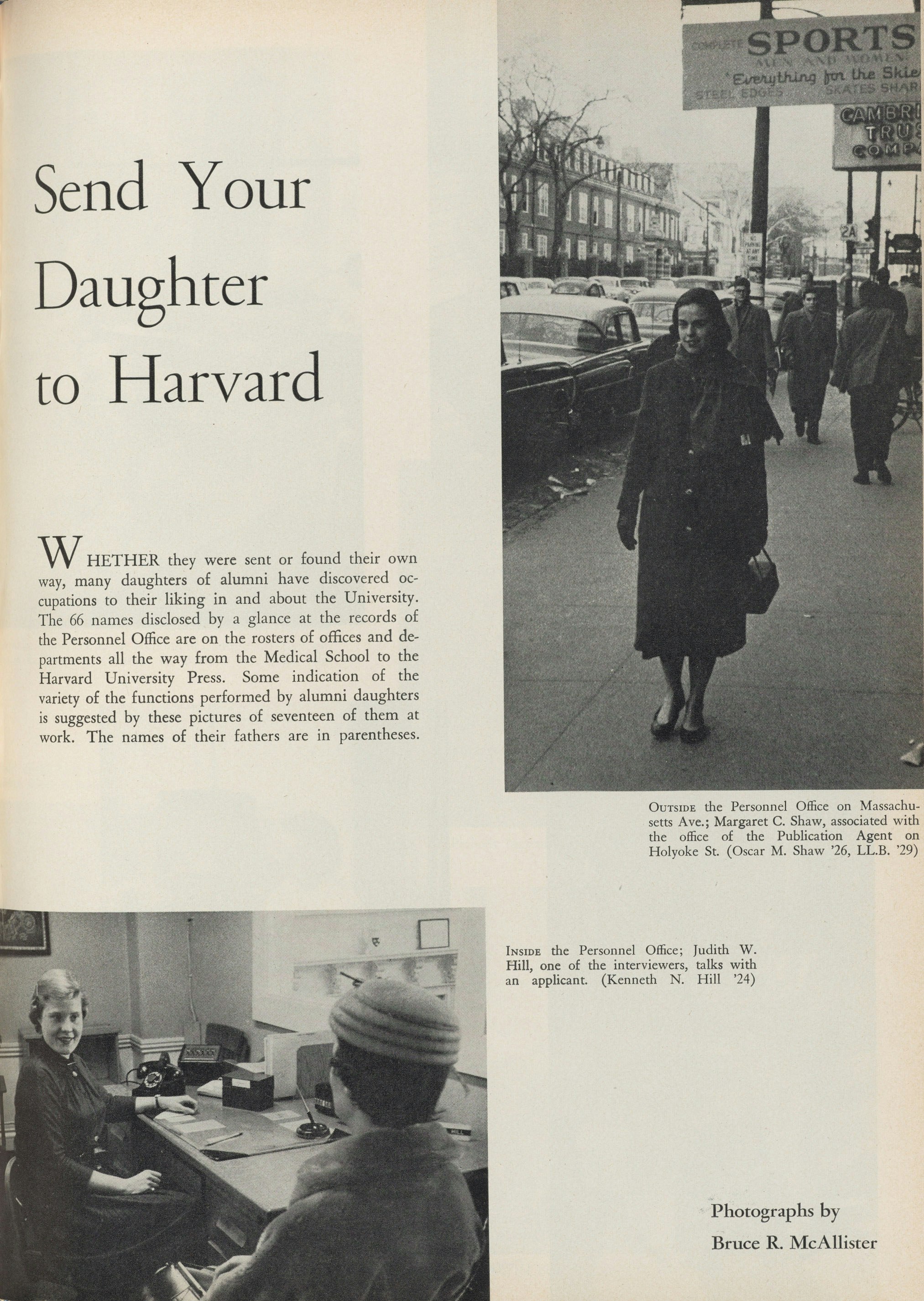

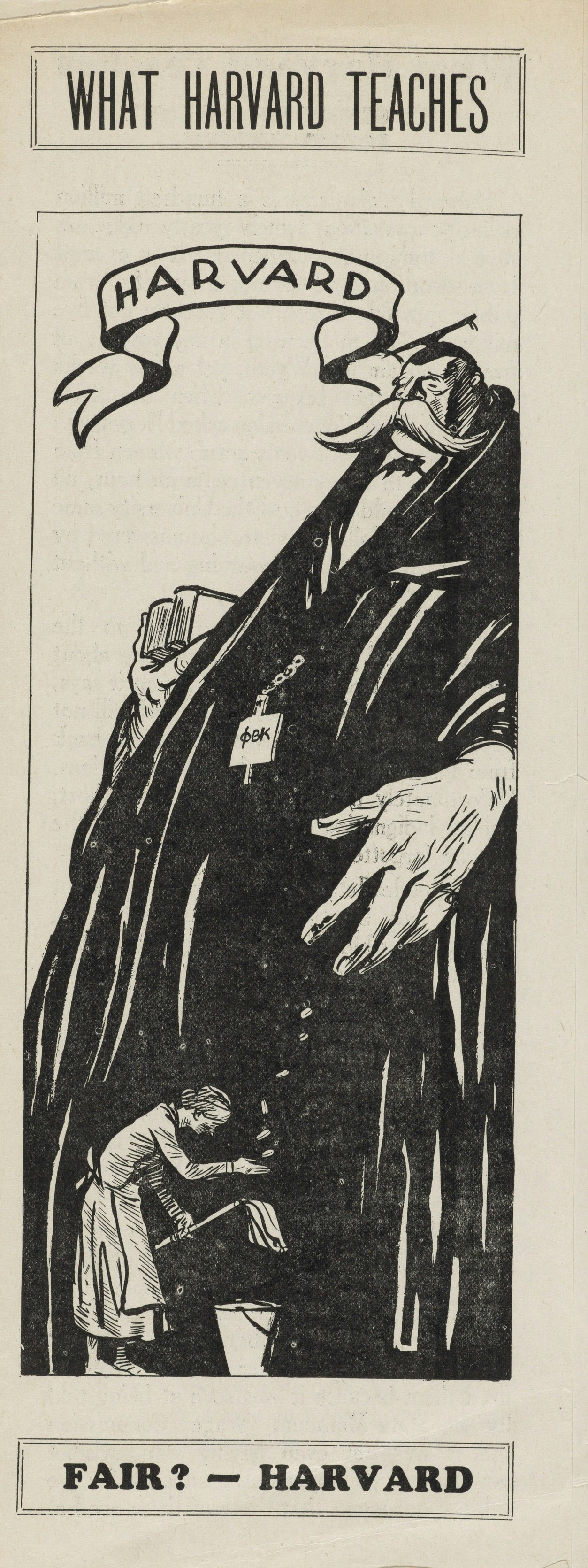

- From the inception of Radcliffe College until its integration with Harvard University, women sought the privileges and resources that were available to male students. Women were denied access to laboratories, libraries, financial aid, and to the lectern.

- But from an early date (1899), women were appointed to responsible positions in the observatory and encouraged to pursue other employment “opportunities” at the University.

- Mrs. Williamina Paton Fleming was hired as a clerical worker for the astronomy department, but soon moved up to the position of Curator of Astronomical Photographs. She cataloged more than 10,000 stars and is credited with discovering 9 gaseous nebulae, over 310 stars, and 10 novae. She supervised women hired to do mathematical classifications who became known as “the human computers.”

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt, class of 1892, was one of the “human computers.” Her formulation of “period-luminosity relationship” enabled the discoveries of Edwin Hubbell and other modern astronomers.

- Annie Jump Cannon, a Wellesley Graduate employed at the Harvard Observatory, received an honorary degree from Oxford and was the first woman to be elected an officer of the American Astronomical Society. She obtained a regular Harvard appointment as William C. Bond Astronomer shortly before her retirement. She coined the phrase, “Oh Be A Fine Girl—Kiss Me,” a mnemonic to help astronomers remember the spectral classification of stars.

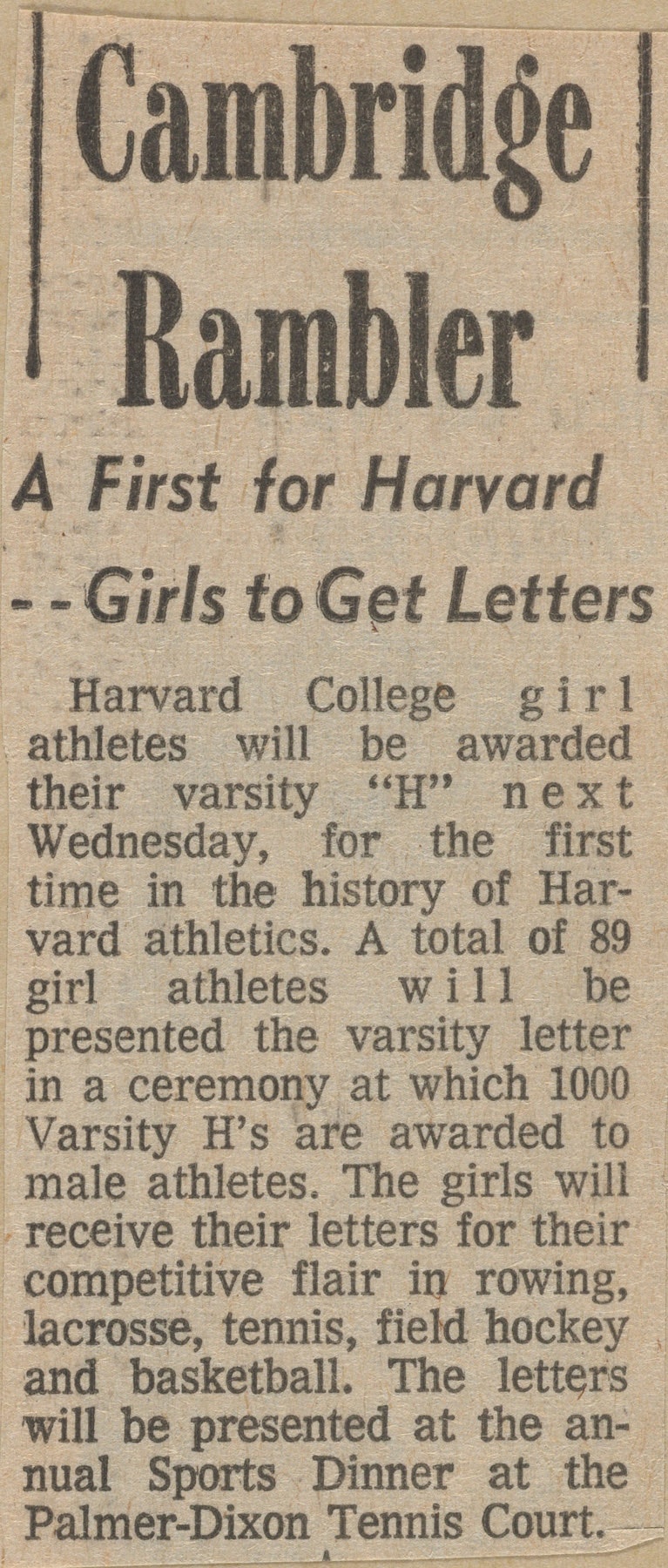

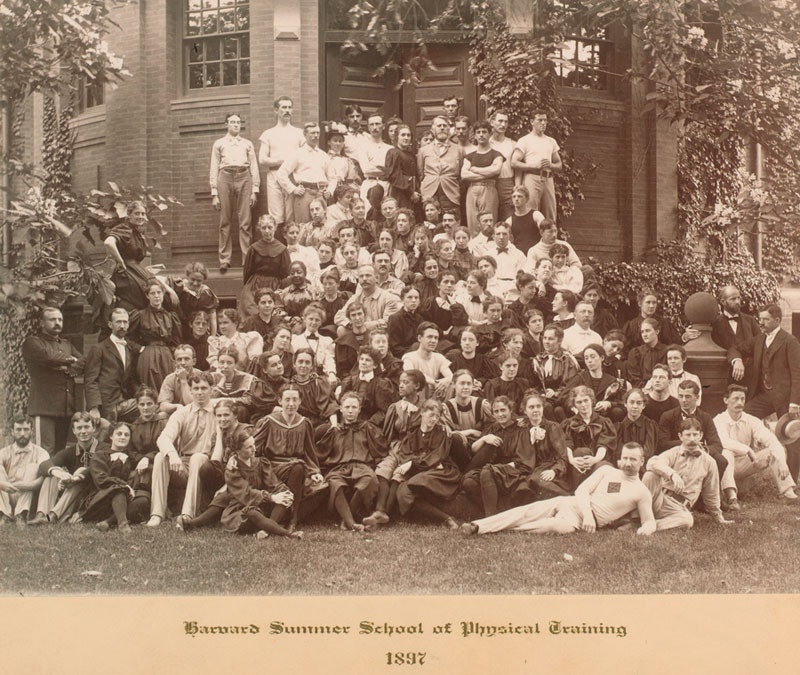

- In 1975 women athletes were allowed for the first time to take varsity letters for sports participation—in rowing, lacrosse, tennis, field hockey, and basketball.

01 / 08

Women at Harvard, 1643–

- Women were “at Harvard” before they were “of Harvard.” From the very beginning, women played many roles, such as providing social support on the domestic front or providing financial assistance through philanthropy. Others were employed across the campus in food preparation, maintenance, and clerical positions.

01 / 07

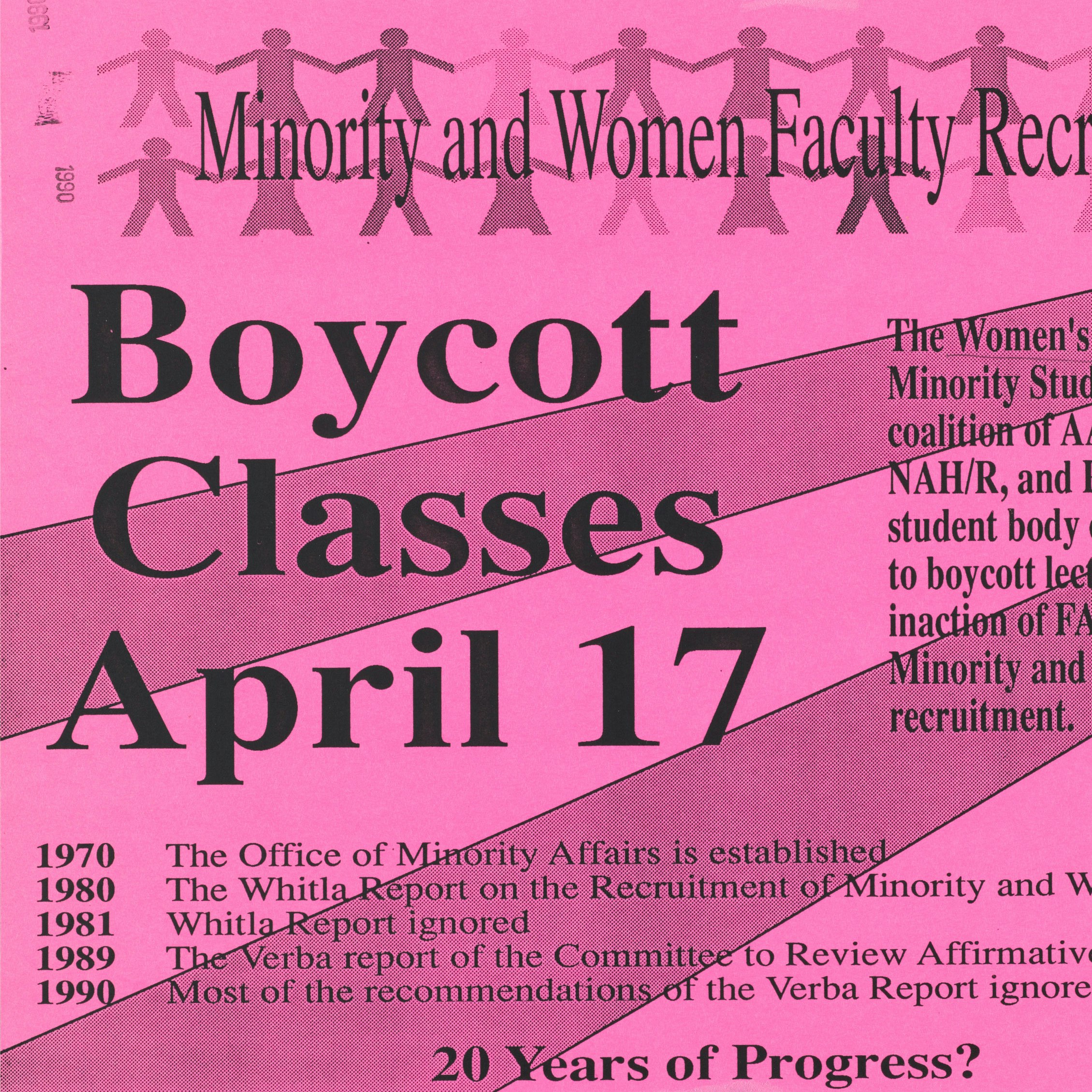

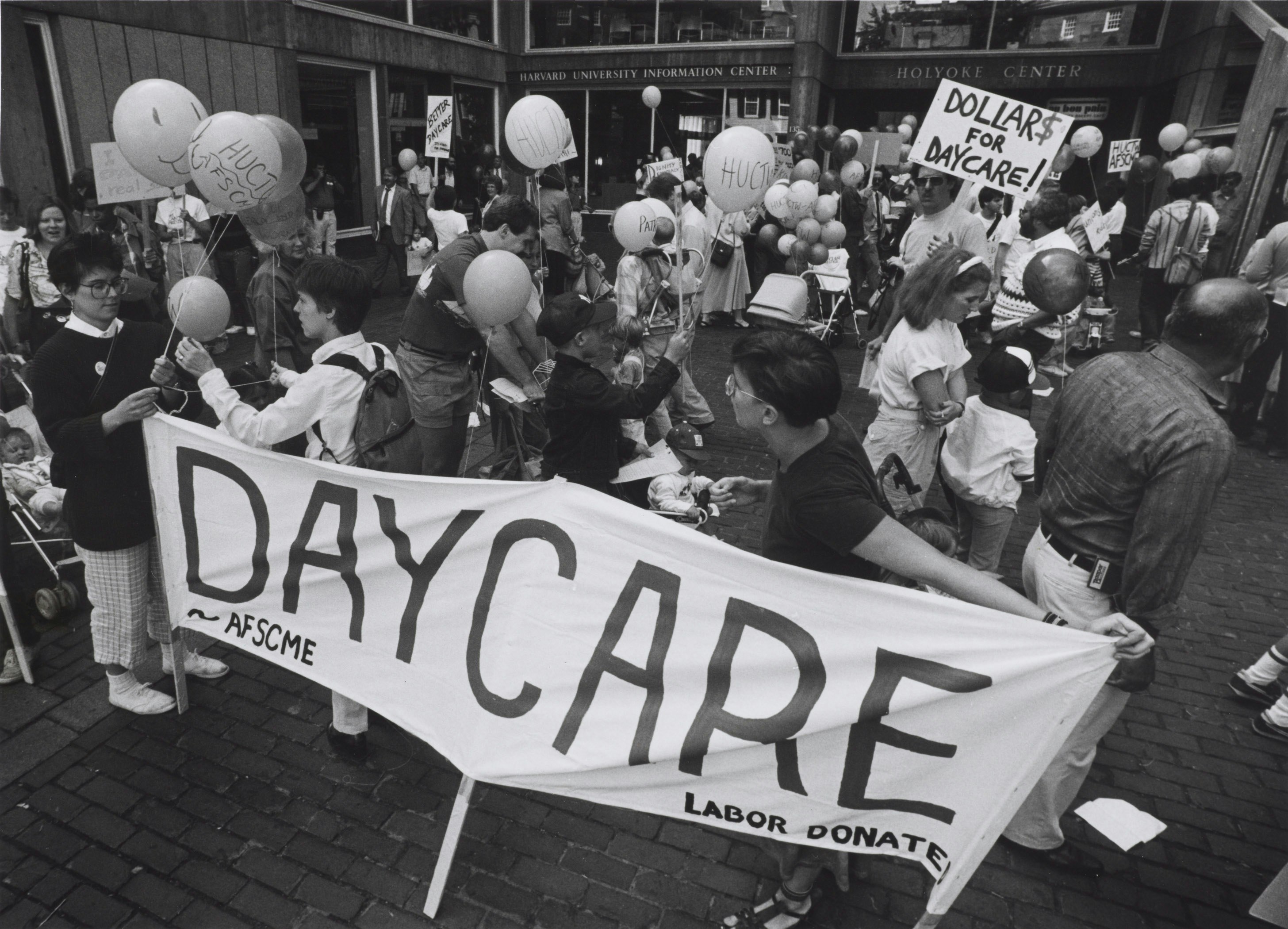

Protesting Inequity

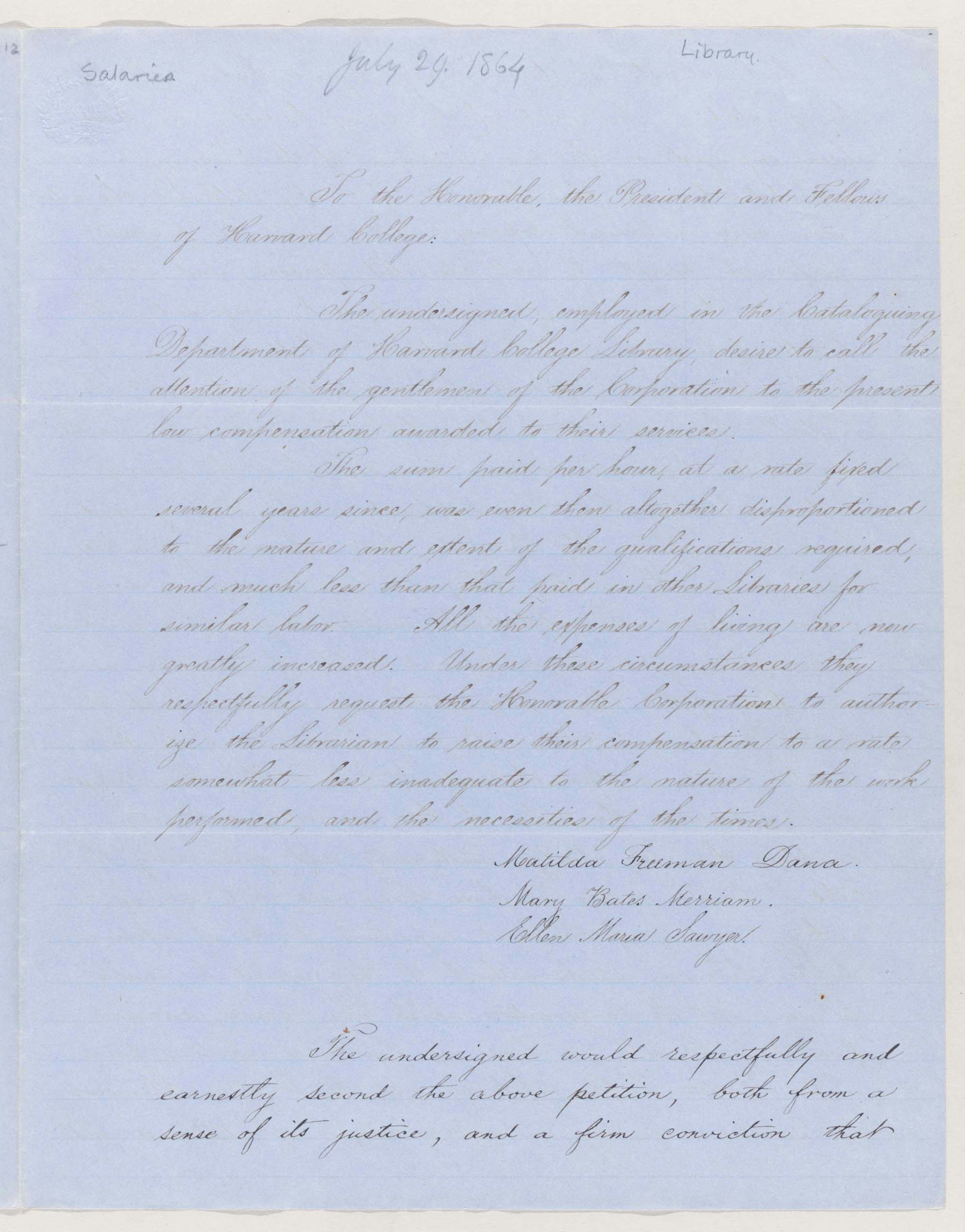

- By letter dated July 29, 1864, three female Harvard College Library catalogers petitioned for an increase in salary stating that “The sum paid per hour, at a rate fixed several years since, was even then altogether disproportioned to the nature and extent of the qualifications required, and much less than that paid in other Libraries for similar labor.” Their petition is seconded in an amendment to the letter (not shown) written by Ezra Abbott, assistant librarian and superintendent of the Cataloguing Department. The last page of the letter contains explanatory notes written by "Mr. Hill" (possibly Thomas Hill, President of Harvard) on September 12, [1866?].

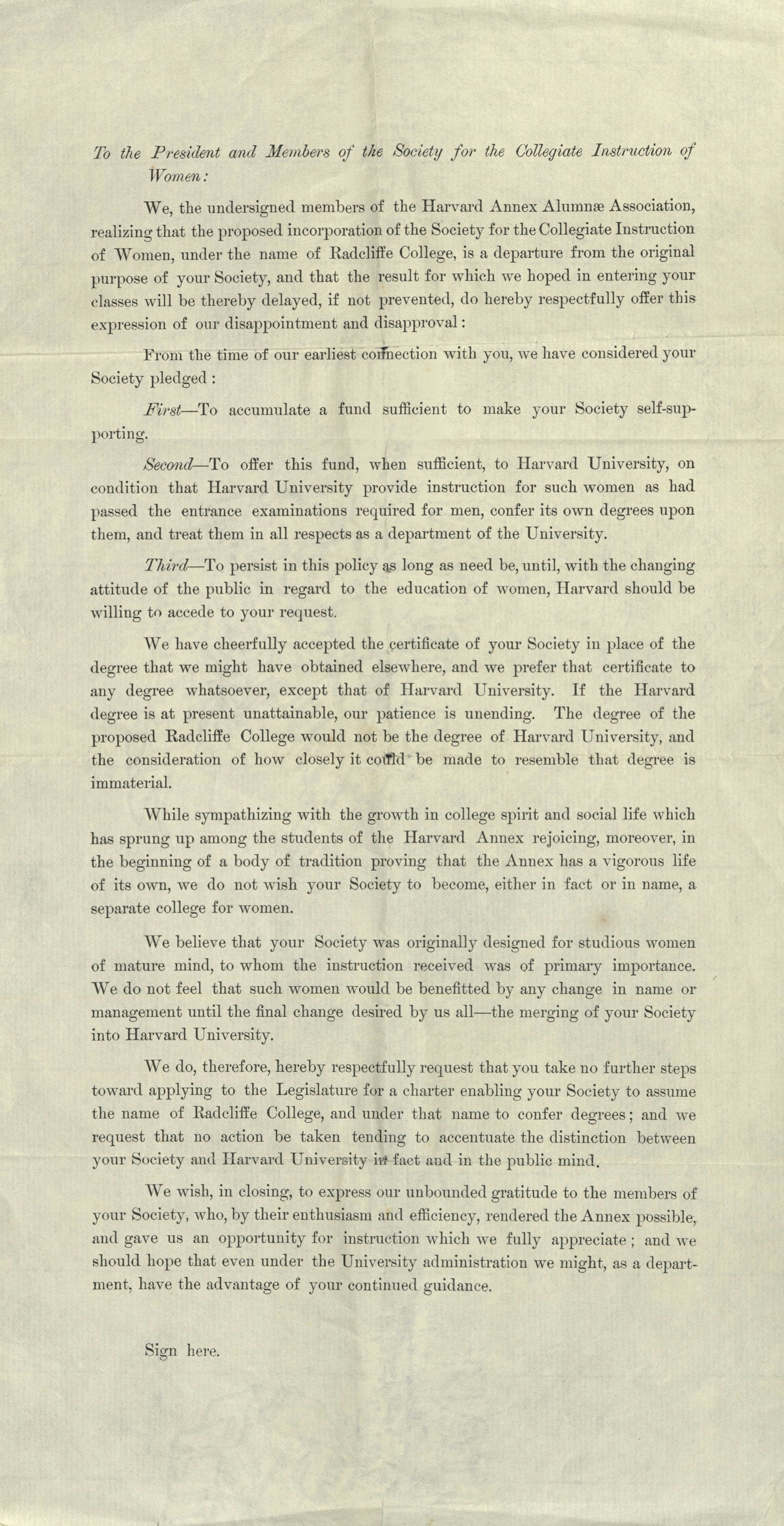

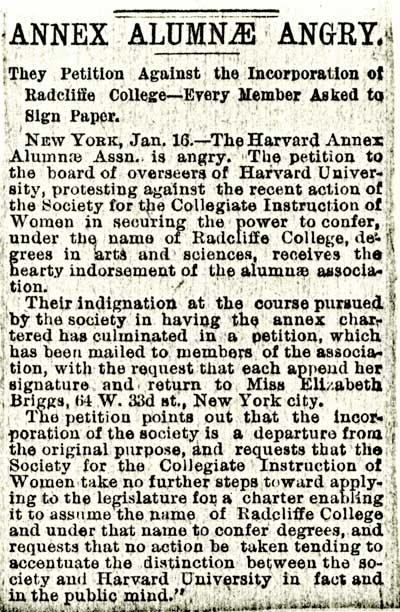

- The petitioners wanted the merger of the Society with Harvard, not a separate college for women.

- After a nearly decade-long evasion of the state’s minimum wage law, in late 1929 Harvard fired cleaning women rather than comply with the law and provide a two cent per hour wage increase.

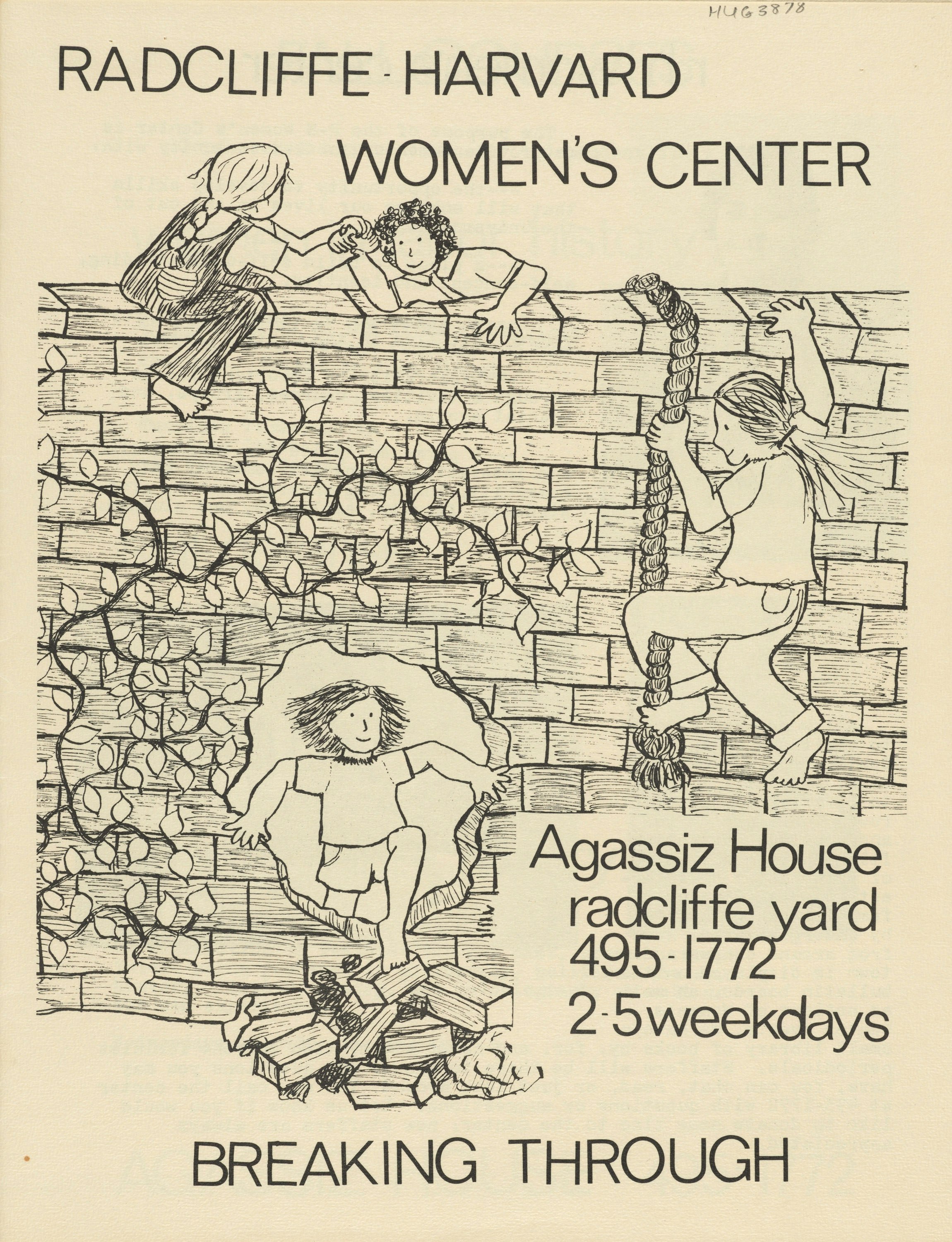

- In the mid-1970s the Women’s Center declared its support for many issues, including “the addition of courses dealing with women’s heritage, literature, sociology, etc. to the curricula.”

01 / 08

Graduate Education and Professional Schools

Harvard Annex and Radcliffe Graduate School

- 1890: AM certificate awarded by Radcliffe to Fannie Holman.

- 1902: First PhDs awarded by Radcliffe to Lucy Allen Paton and Ethel Dench Puffer.

- 1934: Radcliffe Graduate School established as a separate entity.

- 1963: Radcliffe Graduate School merges with Harvard Graduate School after having awarded 750 PhD and more than 3,000 AM degrees.

Harvard Graduate School of Education

- 1920: From its inception, the Harvard Graduate School of Education plans to admit women.

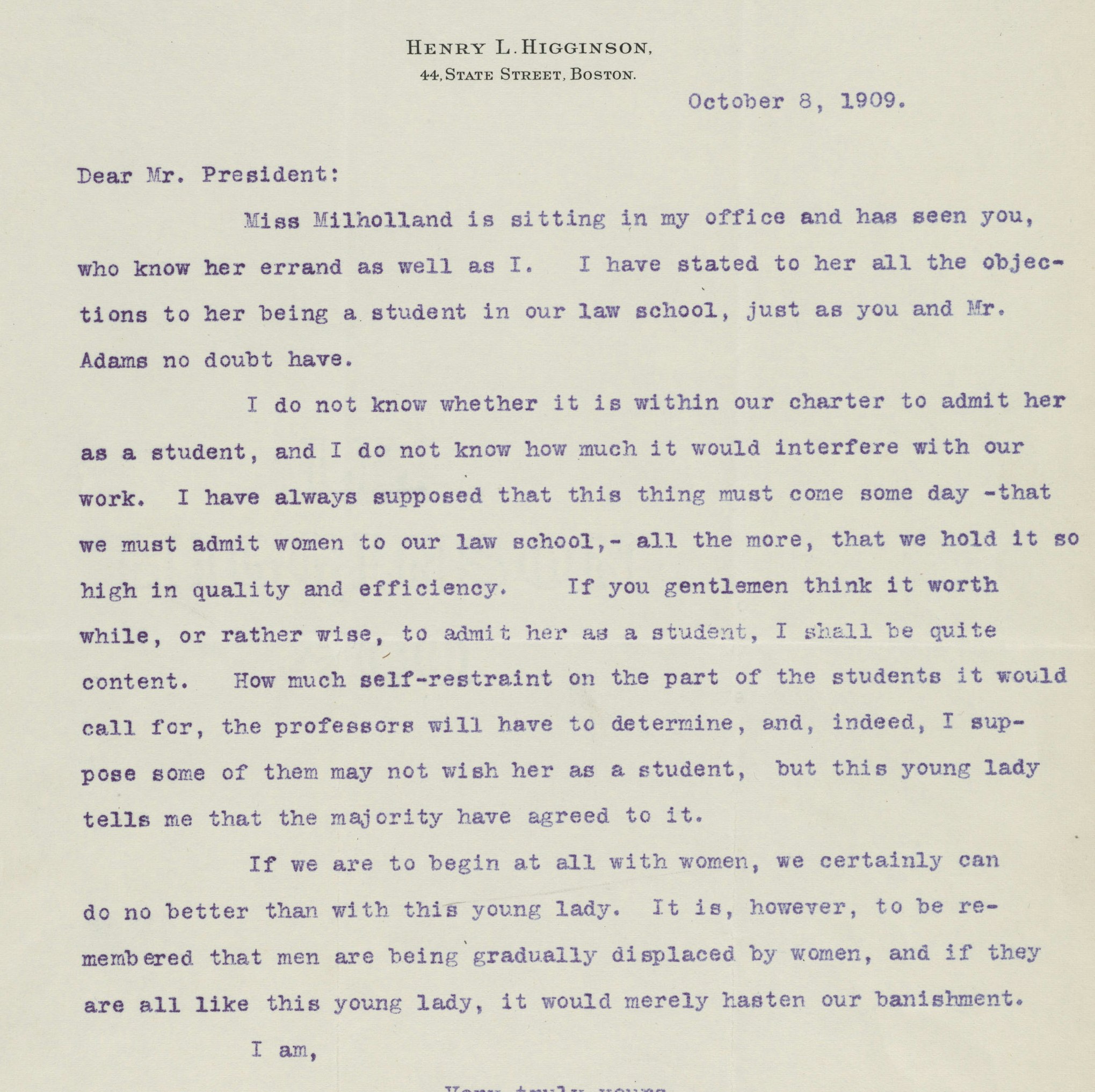

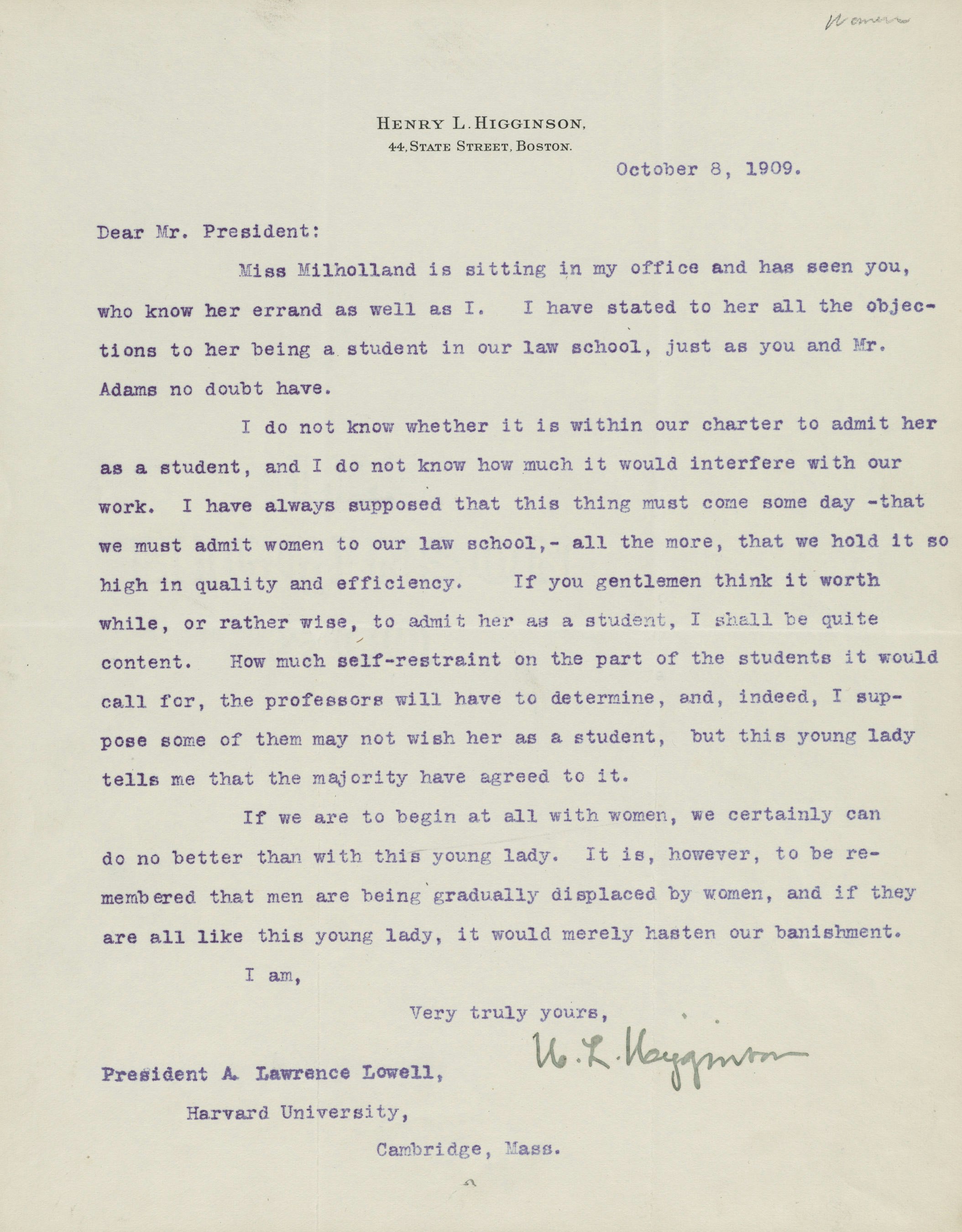

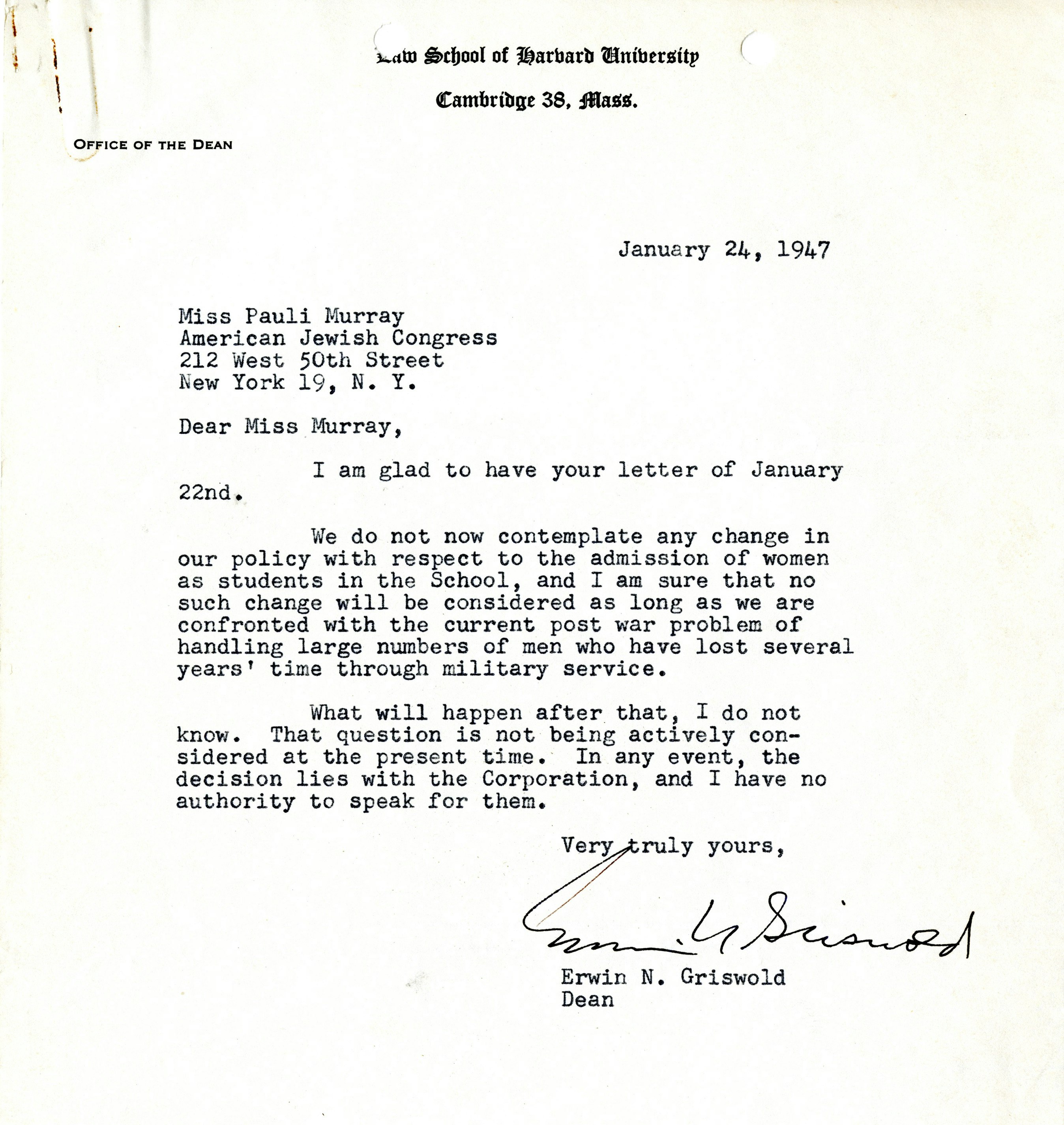

Harvard Law School

- 1909: Inez Milholland applies to Harvard Law School and is declined acceptance.

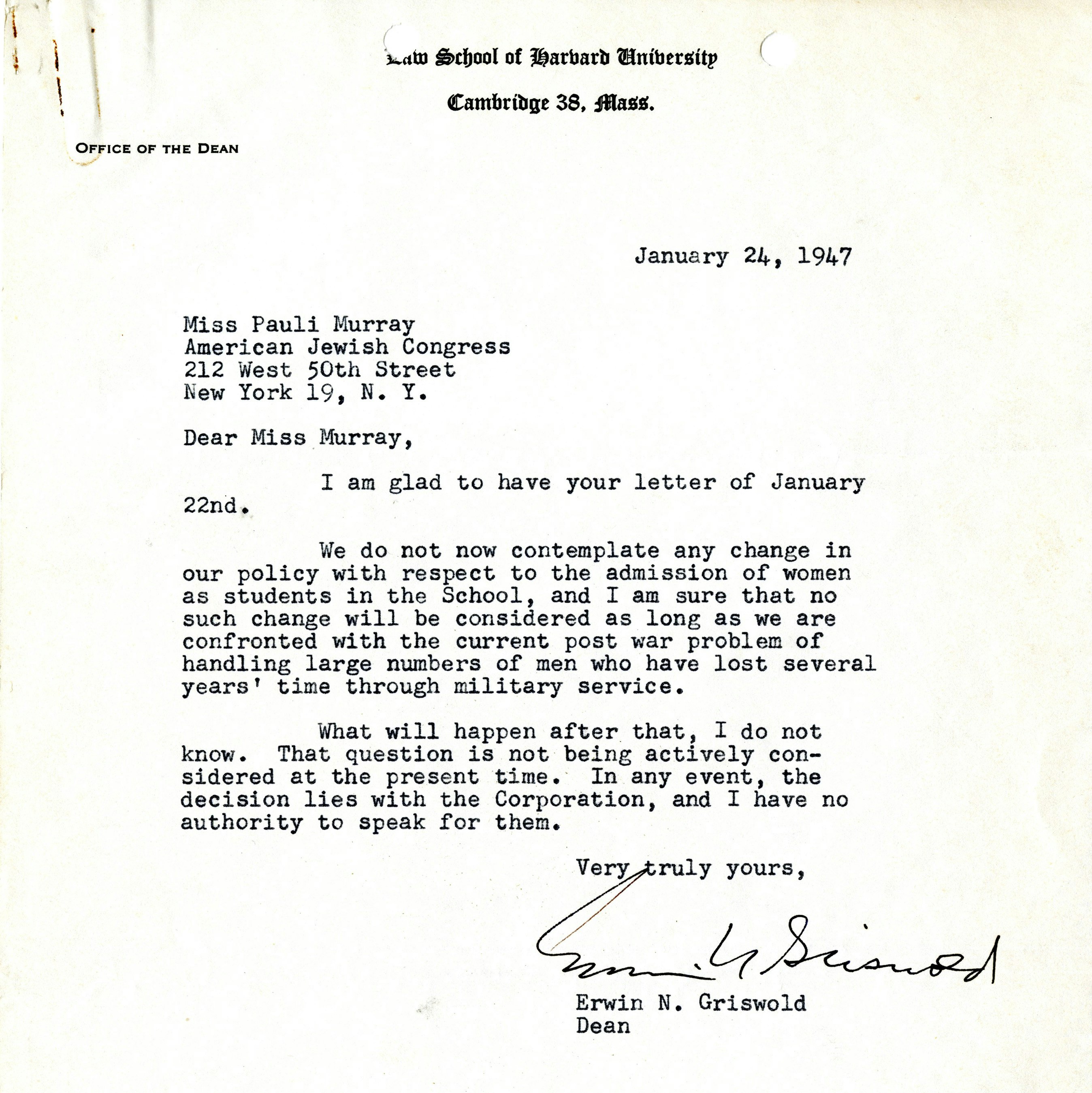

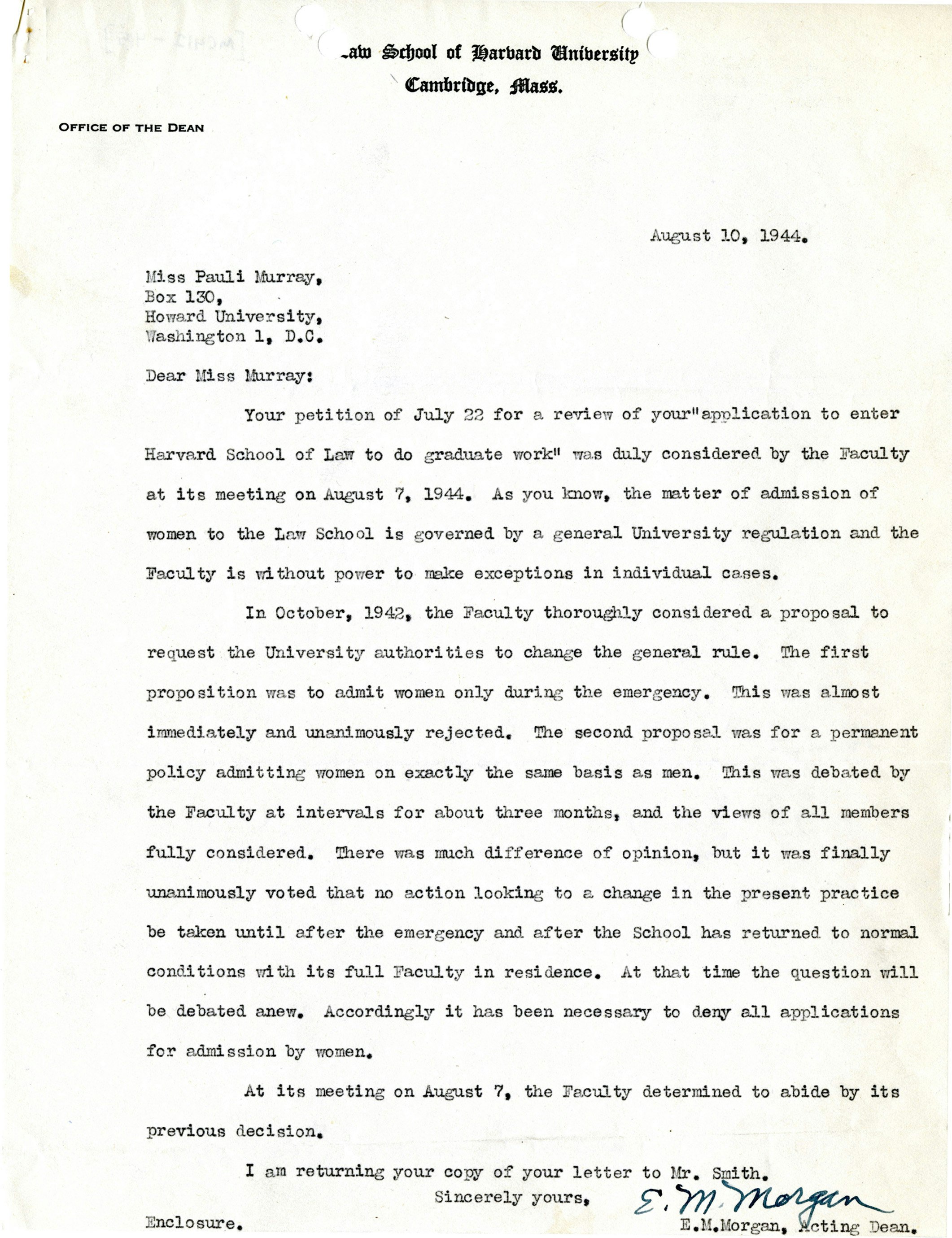

- 1943: Pauli Murray applies to Harvard Law School and is declined acceptance.

- 1947: Following the appointment of the first female Law Professor, Miss Soia Mentshikoff, Pauli Murray once more requests admission to Harvard Law and is declined acceptance.

- 1950: Fourteen women join a class of 520 men at Harvard Law School. Professor Barton Leach institutes "Ladies Day," a single class each month when women students are invited to speak.

Harvard Business School

- 1937: Five women at Radcliffe College begin what Harvard Business School professor Fritz Roethlisberger called “the first daring experiment in ‘practical education’ for women,” a one-year, certificate-earning personnel program.

- 1956: Radcliffe’s business education certificate program evolves to become the Harvard-Radcliffe Program in Business Administration (HRPBA).

- 1963" In April 1963, the first woman accepts admission to the MBA class that would graduate in 1965.

Harvard Medical School

- 1920s: Radcliffe is asked to create a program to train women physicians because of a shortage of doctors; however, President Lowell will not sign degrees. Program is aborted.

- 1945: World War II influences the Medical School’s decision to admit women.

Harvard School of Public Health

- 1935–1942: Dean of Harvard School of Public Health, Cecil Drinker, begins to admit women to the School.

Harvard Divinity School

- 1955: Women are admitted to Harvard Divinity and Appleton Chapel is opened to women.

01 / 08