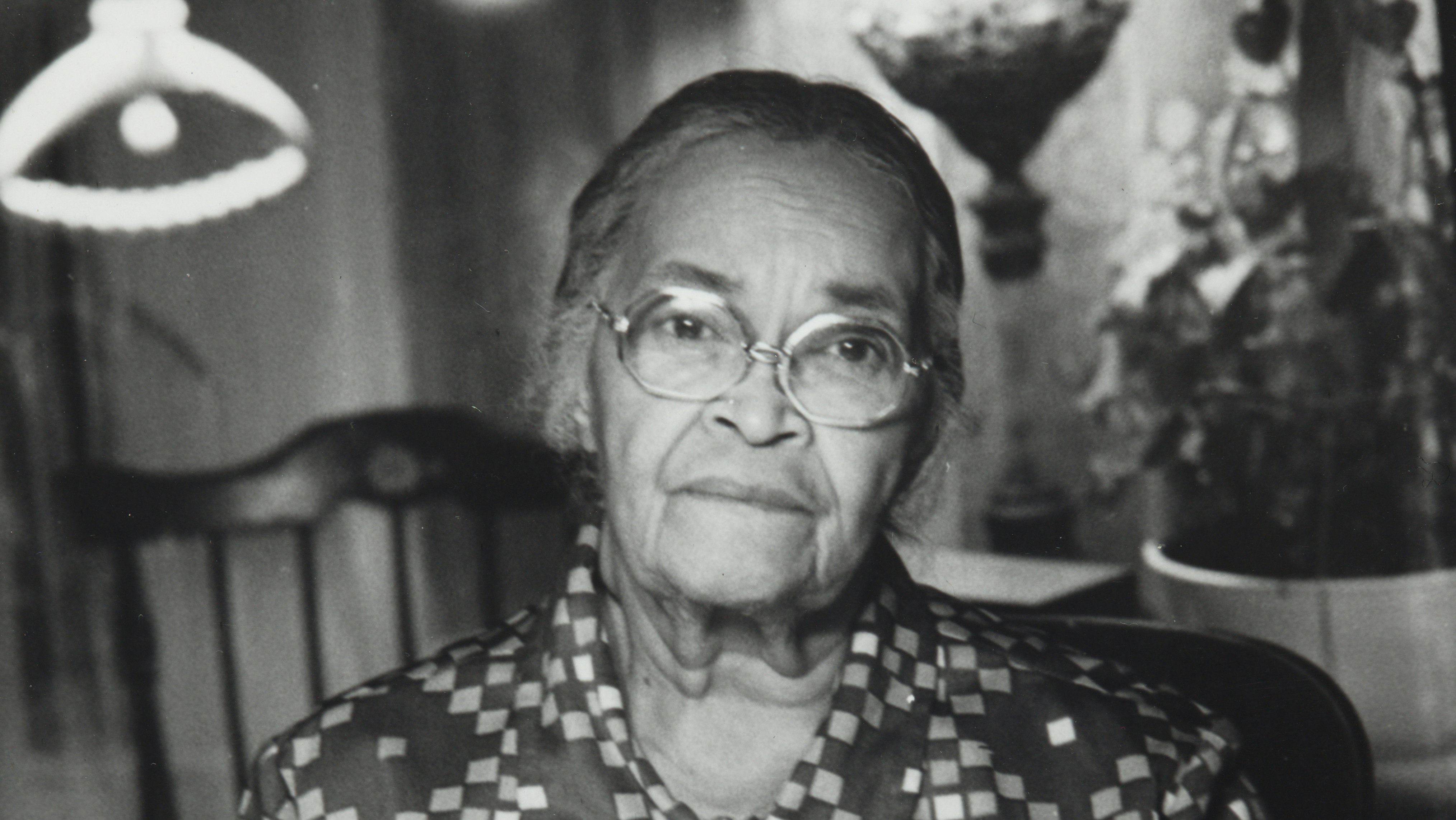

Melnea A. Cass Oral History Interview

Melnea A. Cass (1896–1978), called "Roxbury's First Lady" and "Roxbury's Elder Stateswoman," recalls the Boston Branch of the NAACP staging sit-ins to protest the Boston School Committee's segregation policies within the Boston Public School system.

Cass was active in the NAACP (president, Boston branch 1962–1964); the Board of Overseers of Public Welfare (Boston). "Melnea Cass Day" was proclaimed by the mayor of Boston on May 22, 1966; and she was named Massachusetts State Mother of the Year in 1974. Melnea Cass Boulevard, which runs between Massachusetts Avenue and Tremont Street, opened in 1981.

For research tips and additional resources, view the Hear Black Women's Voices research guide.

[Start of track on reel 3, side 1]

Melnea Agnes Cass [MAC]:

"Balance" was how we started out here in Massachusetts, getting that before our legislature as a supplement to the national idea of investigating the public schools. So we would get our group together, and call it out at a board meeting that we'd want to have a sit-in, and we're going to organize a sit-in. Well, we'd organize a sit-in, you already had that, and we'd get volunteers to do that. And we'd go down there then to the Boston School Committee, and just go right in and talk with them, probably on a little something that we'd want to bring before them. And they never paid any attention to you anyway, so then when they'd get through with the meeting, we'd stay there. That's how you organize it, you stay there. And they want to put you out, and call the police, or they'd do anything they want to. If they want to, but we'd sit there, and um...

Tahi L. Mottl [TLM]:

Did you actually participate in that?

MAC:

Yes, I have a picture. You can look at it in the hall there. They took a picture of me at the sit-in.

TLM:

Had you participated in any sit-ins before that, or were those your first sit-ins?

MAC:

No, I'd been to one before.

TLM:

What other sit-ins?

MAC:

The same thing, for the School Committee. We had two, three, five and ten because Vernon Carter was walking up and down the streets, you know, in protest against the whole thing. Every once in a while, we had a sit-in. Just a demonstration, that's all. We'd march up and down. I'd done that too, in front of the place, with the group, march a certain length of time. Oh yes, and carried a banner and everything. That's just a part of it.

TLM:

These demonstrations came about mainly because of the School Committee?

MAC:

Well, these were. These types were, but there were other kinds of protests beside that, but this one happened to be about the School Committee, and trying to get them to see the point, in trying to listen to what you had to say, and trying to act on some of the recommendations that came in from the NAACP.

TLM:

So did you—You actually went down and carried a sign?

MAC:

Well, I carried a sign a couple of times. That wasn't anything. Because you went shopping, you'd go by... They had the picket line out there going; you'd just take a sign and walk around a little while, and then give it to someone else. That's the way they keep them going. If you could go down a certain length of time, in the day when nobody else could, you'd go. You would sign your name up to go and you'd go from eleven to two, or from twelve to three, or whatever you wanted to do, just to say you participated and tried to help. But of course for the sit-in, that was... One sit-in that I was in, a mostly definite sit-in, was very crucial because we had... a group there, and I thought I wouldn't sit in that day, because I had been to others, you know, and it was tiresome and everything, but theysaid that they were going to arrest them, because they had trespassed and were doing...whatever they were. They said they were against the law, so they called me up, and asked me would I come down and sit-in there, because he said if I did, they don't think they would arrest them, you know. So I went.

TLM:

Who called you up?

MAC:

One of the young men there. So I went down, and I sat in with them at the demonstration. So, uh...

TLM:

Do you remember who was there at the demonstration, who participated? Do you remember any other participants?

MAC:

Yes, the picture's right there. Get the picture. Get the picture, I can tell you the names. Ruth Batson and Kenneth Guscott. Right on the table.

TLM:

Okay, this is the sit-in, "Boston School Committee, 1963."

MAC:

Yes, that's Ruth Batson, Rheable Edwards, Jo Holley, Kenneth Guscott, Hansford Brown. Let me see some of the names. I can't remember. Ruth Batson's daughter, I can't remember her name. And that's Jo Holly, Josephine Holley. [Telephone begins ringing.] That's George Guscott. And that's Ruby—I can't think of her last name. She's a great worker with the NAACP. Some of those I can't remember.

[MAC answers telephone.] Hello. Yes. Yes. Well, I'll do the best I can to get there as I said. I'll be at the city hall. I'll take a cab and come out there. I'll get there before they get through anyway. All right. Bye. [MAC hangs up telephone.]

Most of those were people who were very interested in...

TLM:

Anyone else you recognize?

MAC:

I can recognize all of them but I can't call their names; too bad, but that's the way my memory is. But most of them I called there.

TLM:

So most of the audience here are members of the NAACP.

MAC:

Yes, they're all practically, were all friends of it, or interested in the bill that was up before the legislature, trying to get the School Committee...

TLM:

Where... Oh, this is at the School Committee.

MAC:

That's on Beacon Street.

TLM:

You weren't the president of the NAACP at that time?

MAC:

No, not then, no. I had finished my term, I guess. Kenneth was the president. He was the president under that. But we had them in my time too. Just about the same thing.

TLM:

Was that the demonstration you went to where they were going to arrest you?

MAC:

Yes, and he said if I would come... He said, "I think if you came down here, they wouldn't arrest us, because they wouldn't dare to do it." So I said, "Well, I'll come." So they sent for me and I came down. So when I came down the policeman said, "What do you want?" They knew me too. I said, "I'm going in to the sit-in, to the demonstration." "Oh," he said, "you are?" I said yes. So he opened the door and let me in. They were locked in there. So he said, ooh he said... Well anyway, when I got upstairs, I went and I sat down with them a long time, so the police officer said, "Well the time is nearly up, you have to leave."

TLM:

Were you in there for several hours?

MAC:

Oh, about an hour or two, maybe. A couple of hours. And so finally, he...they must have called up the station house, or the precinct over that way and told them I was there. So the captain said, "Well, then you can't arrest anybody." He said, "If Mrs. Cass is there, don't start any arrests." So we stayed another hour. We got the message from somebody, that said they weren't going to arrest anybody. So that was what they felt, that I saved the day that day by being there. So that was quite an affair that night. The streets were full of people, they were all out there demonstrating. You see, there was a demonstration going on.

TLM:

When this picture was taken?

MAC:

Yes, we were inside demonstrating and they were outside demonstrating. A couple hundred people in the street, I guess. They were getting so tired of it, you know, trying to get something done, and they couldn't do it, so they were just going to sit there. They were going to sit all night if necessary. So they did it. They went out, oh, about one o'clock at night, I guess, we marched out.

TLM:

And then you came home?

MAC:

Oh yes, we all came home. Everybody came home. They brought you home. They had cars and everything else. So we came home.

TLM:

What was it like? Was that an exciting time, or exhausting? Or was it sad?

MAC:

Well, it was... No, it wasn't exactly exciting, but it was sad to think that you had to do all that, just to get your point over, you know. It just really made you feel very depressed, to think you have to keep on doing that. You can't make a headway at all, make a little dent in the thing, you know, you'd like to just feel like you were progressing, but we weren't, you see.

TLM:

But was it also exciting or no?

MAC:

Yes, it's exciting in a way and in a way it wasn't. We didn't take it as any kind of excitement or anything; we took it as a very serious thing, and a calamity happening to us as Black people, trying to get something done, and couldn't impress anybody. That was the whole thing. People were... You could see from faces of the picture I showed you, they're all very serious and depressed and very worried.

TLM:

How was this different from the meetings that you described that were organized by William Monroe Trotter?

[sound of airplane passing overhead in background]

MAC:

Well, there's quite a difference, because it's a different issue. This issue here is right at your hand, and with the children of today being shortchanged in their education and all. His was getting jobs for people, and protesting against lynching, and all that kind of thing, but this was right here in our own city, and our own kids, grandchildren and kids who were real being cheated out of an education. You're trying to get the door open for them somehow or other. This girl, Ruth Batson, was one of the leaders in this movement, in this whole education movement. She was a very faithful worker in the NAACP, one of the staunch supporters of the NAACP. She and Jo Holley there, Josephine Holley, and Rheable Edwards and her husband Ray, all those people were really people who sacrificed a lot for the NAACP, who worked faithfully, and in fact all those people there, that's just a segment. There's many more.

TLM:

How about comparing this, the demonstrations and meetings during the School Committee events with the meetings that A. Philip Randolph organized.

MAC:

Oh, those were entirely different. They were just as enthusiastic meetings, the people just as serious about it; everybody is serious about the issue as it comes along. That was a vital issue, because it's bread and butter, and jobs for men. The homemakers, the home people, they wanted to make a living. All of them are just about as exciting as one another, but they're all separate subjects, that's all. But the motives are all the same; it's to open the door of employment and equal opportunity for Black people, whether it's the school, a job, or what it is. That's all it is, just asking for fair treatment. And that's what Black people have had to do ever since they were freed in this country. They've been trying to work to get their equal rights with everybody else. It's very frustrating; every time you turn around, you got to have a demonstration, you got to have a law, you got to have something to give you, that tells you that you're free and that you're equal to everybody else, but when you go to test it out, it's not true. So when you go to test it out, and it's not true, you wonder what is wrong. Why have you got to do all these things, to make people understand that you're entitled to these things? It’s just that simple. So every time you pick up an issue, it's an issue related to something, but it's just as important as any other one. All are a piece of the whole thing.

TLM:

Well, tell me about, going back to the school issue. The School Committee didn't respond to the demonstration.

MAC:

No, no, of course they didn't respond to the demonstrations. If they did, you wouldn't have what you have here now, if they had corrected these things years ago, when we asked them to do it. And we saw the racial imbalance going on in the school, and the inequality in the curriculum and everything else, and tried to tell them to correct it; they could have done that. You wouldn't have any need for the Supreme Court to tell them, "Go ahead and desegregate those schools. We don't care how you do it. And you only got so much time to do it." You wouldn't have that. But this is the result of not paying attention to what you should have corrected a long time ago and prevented this. You can see that. You know?

TLM:

Did you remain active in the NAACP up through the time of the court suit?

MAC:

I'm still active, dear, in the NAACP. I have never stopped being active in the NAACP, since I joined it as a young woman. I have been active in it up until today. I just went to the installation Sunday and was sworn in again on the board.

TLM:

Oh, so you're a member of the board?

MAC:

Oh, I am a member of the board, elected to the board every year.

TLM:

Tell me about the period when the NAACP was suing the School Committee to desegregate the schools. Do you remember?

MAC:

They weren't suing them. They never have sued this School Committee. You couldn't sue the School Committee, dear.

TLM:

Oh. Well, then, the Garrity decision is what I'm talking about.

MAC:

Oh well, the Garrity decision is what's going on now, that we're all interested in, that everybody's interested in, and the NAACP is the one that brought the suit. They brought the suit in the beginning.

TLM:

How did that come about?

MAC:

Because we couldn't get the desegregation any other way. So they carried a suit, to show the mothers who said their children were being shortchanged, let them tell the court themselves, and ask, "Would you please do something for my children, and all the rest like them." That was all. It was just a suit, brought to open it up and let the court know that we still want it done, see? That's all. It wasn't anything really that we could do about it. All we did, the lawyers that took the cases were well-qualified lawyers here in Boston, some of them did it for nothing. No money at all. They just wanted to do it as a civic duty. Because they know it's wrong and they want to help it. All of them. So they got these mothers whose children go to these various schools where all these inequities are going on, so they could come up and say, "Here it is. I know, because here is my child to do it." All we did was back it up and try to support them in it, that's all. We couldn't do any more. And of course, when it went to the Supreme Court in Washington, the national NAACP took the whole issue to the Supreme Court. That's when they said, "You got to desegregate the schools of America. All of you got to do it. Where it's found that there is a need, you've got it to do." So when they told Boston they had to do theirs, they ignored it. Didn't even pay any attention to it, tried to get away with it, like they were doing when we asked them, but they couldn't do it. Because you see, that's a different kind of agency telling them now. We were nothing as far as they were concerned. They had just listened to us, and let it go ahead. But when the Supreme Court said it, they knew they'd have to do something. Because they had a chance, when we brought the racial imbalance bill, to get a plan ready. We asked them to get a plan ready, to desegregate the schools. But they didn't bother getting any plan ready. So you see, that's why they resulted in the Supreme Court coming into the case, because there was nothing being done. They had to be made to do it.

TLM:

By the Supreme Court, you mean Judge Garrity making his decision?

MAC:

Well, of course Garrity was assigned. He's nothing in it so much. He isn't the main thing. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People brought the suit to the United States Supreme Court through their legal department, to get the thing regulated all over this country, and stop talking about it. So it passed in the Supreme Court, that this had to be done in all the cities. Garrity is just one of the Supreme Court judges assigned to Boston. There are others assigned to other cities where this existed. But he is the one that had to carry this order out, because he's Supreme Court...he’s on the bench, he's assigned to this job. And they want him to do it; so he's doing the job for the Supreme Court; he isn't doing it for the NAACP. No, he's doing it because he was assigned by the United States Supreme Court. But we're involved in it, but they're not doing it for us.

TLM:

Okay tell me about the Women's Service Club. It says on your biography that you were the president, or have been the president of the Women's Service Club for fifteen years. Now, that's past tense—when, what fifteen years were you...?

MAC:

Up till now. Fifteen before this. Right now I'm president of it. Right this day, I'm still the president, so fifteen years have passed since I've been president, and I still am the president.

TLM:

What's the address of the Women’s Club?

MAC:

464 Massachusetts Avenue. And it was founded by a group of women who I told you some time ago worked together during World War I for the veterans, and when it was over, they decided to continue community service, and bought this house on Mass. Avenue, and decided that they would try to do community service in the neighborhood, whatever it would be to help the people. So they bought the house, and their first project was—besides community service programs, educational programs, and all kinds of things for young people and old people—was to open up the doors for girls who came here to go to college, who couldn't get places in the dorms, to live here, and they lived there, quite a number of young women lived there for a number of years. They had a housemother; they furnished the rooms upstairs, and beautiful bedrooms for two in a room, three in a room, and made the rents very reasonable. Average was $10 a week, some of them, and some less, if they couldn't pay it. And they had a home there. And a good many fine young women, who have gone out from Massachusetts, lived there while they were going to college. Then when the [dormitory] bars were lifted on account of the desegregation change, and they were eligible to live there, that's the time, soon after that, that I came along, and we began to work with the girls from the South, who came here looking for jobs. And we called our program the In-migrant Program, and that's how we established that. About ten years ago, maybe ten or twelve years ago. So we were funded for that program by ABCD [Action for Boston Community Development] and as a part of their social service programs in the city of Boston.

TLM:

Was this for girls mainly from the South?

MAC:

Yes, mainly from the South, West Indies islands, the Caribbean, and Haiti, and all the Black girls particularly—and if there were any poor white ones, all right, but we didn't have any white ones—who came here looking for work, disillusioned and disappointed when they got in the work, and found they couldn't do it. Came out of the urban centers of the South, where they really didn't know about doing this kind of modern work that you had with vacuums and electrical appliances, et cetera. So they would go to work and get very disappointed. So Traveler's Aid sometimes would send them to our house. They'd be sitting in the station, bus stations, waiting for these people [employers] to come get them, and they never showed up. So we'd bring them to our house, and we'd train them and tell them how to work, and try to find them a job if we could.

TLM:

What sorts of work?

MAC:

They were doing domestic work, you know, that's what they came here for. They didn't know anything else. They were picking cotton, you know, out in the fields, and all that kind of thing, and they heard, read it in the paper, that there's an agency down South would pay your fare to Boston to another agency, and give you a room in somebody's house, and you could work and make thirty-five, forty dollars a week, and all those things, your own TV, and your own this and your own that. Well, some of it turned out to be pretty good. Some of it didn't. So we were there, and we naturally could help some of them that we could get a hold of and show them, you know, the way to live in Boston, where to go and this and that. So that's a program we had for quite a number of years. And we still got the program going.

TLM:

How about the Homemaker Training Program?

MAC:

Well now, that was a different thing. That's an offshoot of the In-migrant. And that was the program that we found we needed to get something to teach these girls how to work, what to do, training in this work. So we just got together, and tried to do it, and at first, the ABCD did stretch it, the money, to help us to do it. But we didn't have the facilities there, you know, to do it the proper way. And we were going to try to raise money and see what we could do. So finally, I don't know how they heard about us, but the Department of Labor heard about the program that we were doing. And they asked us if we'd like to be a pilot program in the country. They were going to try to Improve domestic work for people. And they heard we were doing it, so they wrote us a letter, and we answered and sent them a proposal, and told them what we were doing really, and so with the Department of Labor and the Department of H.E.W. [Health, Education and Welfare], we got a grant to do the training of these girls in Boston.

TLM:

What year did you get the grant?

MAC:

About eight years ago now. And they took the initiative, and really remodeled our cellar and made it into a kitchen, beautiful facility, where they received their training. Right down in our cellar; they remodeled it and paid for everything in it. We didn't have to pay any money. And they gave us a proposal, well, they gave us a budget, in which we were able to hire a director, a home economics teacher, a job developer and a secretary and a social worker at the beginning. And we advertised, and we told about what kind of program we were going to have, and we were able to set it up right there, and train these girls, and the Manpower Development Labor department helped us with it, beside the government giving us the budget. I forget what our first budget was, but anyway, it was enough to cover all this administration. And also we got donations from the gas and electric company. We got a Frigidaire which the electric company donated, a stove from the gas company, and we got a lot of things donated, after they found out what we were doing. The budget called for one Frigidaire, or one this and that, so we had two things there now of each thing almost, so that they can learn on both, gas and electric.

TLM:

I see. About how many women go through the program each year?

[sound of airplane flying overhead in background]

MAC:

Well, we can have seventeen in a class, and a class is for twelve weeks, and at the end of the twelve weeks, there is a graduation. We begin all over again with another group.

TLM:

Are the women who go through still pretty much women who come from outside of Boston?

MAC:

No, not now. In the first beginning, it was mostly women who were from the South, and who were wandering around, but it is for all disadvantaged women, any of them, in the city of Boston now. So we don't have any trouble training them, and some of them go in nursing homes, some of them go out to families, some of them go in hospitals, they go in all sort of related fields.

TLM:

And about how old are the women?

MAC:

Well, most of them... We've had them up to sixty. Yes, they can come up to sixty years old. Their ages vary; some are very young, nineteen, twenty.

TLM:

So who else worked with you on the development of those two programs?

MAC:

Well of course the women from the Women's Service Club, the members were very active with it, but we had community people who knew what it was all about, who really drew up the proposals for us. We had two or three young people. One is Dorothy Parrish, who is now president of our auxiliary, and she and Rheable Edwards, and two or three young men in the South End—I can't remember their names this minute—who really worked with us and got the proposals ready, because they wanted us to understand what it was all about and how to do it. We didn't know anything about it. Of course at ABCD we got invaluable help because I was a founder of ABCD, one of them. We had plenty of help from there. Those are people who knew the problem.

TLM:

When did you help found ABCD?

MAC:

When it was organized. I forget how many years ago, but that was during the urban renewal period.

TLM:

The forties, the fifties, the sixties?

MAC:

'Round in the fifties.

TLM:

Who else was involved in the formation of ABCD, just as an aside?

MAC:

Oh, ABCD was formed by the director, really it was the idea of Ed Logue, who was the director of urban renewal [Boston Redevelopment Authority]. He told the mayor, who then was John Collins, that they needed a social service agency or humanitarian something for these people whose houses they're tearing down and taking away, and he said there had to be something else besides just walking in and telling them you're going to take their house and you know. So the mayor thought about it, and he said he guessed that was right, and he called together some people, community-minded people, to talk about it, and we went down to city hall and talked to him, and thought we better get it going in some way or other. That was Freedom House, with Muriel Snowden and Otto Snowden, and all of us out here in this area. So we finally—he applied to Ford Foundation, who gave the first million dollars to get this whole thing started.

TLM:

And you were on the board in the beginning there?

MAC:

Yes. So they decided we would have the money, and go ahead and form what we called Community Action Program, and that’s all we had at the beginning, talked about community action. It had to be incorporated, so there were quite a number of men called to incorporate, and I was the only woman, so I'm the only woman incorporator for the city, for ABCD. Because I've been on the board all the years of its existence, and I am now an honorary board member.

TLM:

Oh, that's something.

MAC:

I feel very proud of that, and when they brought the people together to incorporate that day, I was looking around, and I said to the mayor, "This is kind of discriminatory, just one woman." He said, "Well, you represent the whole community, and you can do that very nicely." [laughs] So I was the only community person on it; the others were business people, and people who were going to put money in and try to promote it. It's quite an experience, that ABCD, because it turned into... after the urban renewal became a permanent fixture you see in the city of Boston for community action amongst the poor, and they have all sections all over the city of Boston really working hard with community activities.

TLM:

Well, tell me something. To put you on the spot about the ABCD board, if you were the only community person and the only woman on the board, do you feel that in some ways you were a token member of the board?

MAC:

No, I don't feel so, because I was with the urban renewal when they first started it, and I worked right along with it, all the years that we were out here, and I was still working with it, and trying to do my part in it, you know; so I don't think they were trying to make a token, I think they were just trying to have different segments represented and as you read the names, you could see what they represented. All the different agencies, all the different other things. This was urban renewal for this section of Boston, this was just up here. It started up here by Washington Park, so they didn't have two or three people, they just had one. That was in the incorporation papers, but when the thing started, oh, my goodness, there was loads of people from all sections of this area put on it, to represent this section.

TLM:

Thank you. I see from your biography that you're a member of Board of Overseers of Public Welfare?

MAC:

I was, but that's no more.

TLM:

What was that?

MAC:

Overseers of Boston Public Welfare were the group, board people, who were set up to help the Welfare Department to administer the services and the money that's necessary to go into welfare.

TLM:

Oh, when was that? How long ago?

MAC:

Well, I guess I was on it about ten years, I guess. And before me, there was another Black woman, Mrs. Beulah Hester was on it, and then I replaced her. And when I went on, there was only just one Black, and that's when I really felt that was a token, but of course you can only have so many members. Because they were to administer and advise the mayor and so forth, and the Department of Public Welfare.

TLM:

What mayor was that?

MAC:

Collins. He was the mayor. And this was the board to advise him and others on what was necessary to be done for the welfare, to make the thing move along better. That's all that was for. They called it overseers.

TLM:

But you were on that for quite a while?

MAC:

Yes, I was on for ten years. And now, since the state is really the administrator of welfare, it moved from the city to the state. Some of us were retained, and I was retained amongst the others to oversee, not so much the welfare, but the trust funds that were left to the city of Boston for the poor of Boston, and there’s millions of dollars in these trust funds. Charitable trust funds.

TLM:

Oh? I don't understand.

MAC:

People left as far back as 1700s and 1800s, and they left small amounts of money that’s grown into great big sums, and now we administer that, and see that it is given out in the right directions, according to the fund that is named, what they want done with it.

TLM:

Is that a board?

MAC:

Yes, a board.

TLM:

And you're still on it?

MAC:

I'm still on it, and more people have been added to it, but I'm one of the old leftovers from the Overseers of Public Welfare. I’m still on it.

TLM:

And how often does it meet?

MAC:

Once a month. They just called a meeting. It meets about once a month.

TLM:

Oh, this was one of your phone calls?

MAC:

Yes, one that is going to call me back. But once a month we meet. Supposed to. And see what fund is eligible to be given out, where it's going. People can apply, groups of people, for projects or whatever, if it can be done, it can. There's a good bit of it given to scholarship to help children on AFDC [Aid to Families with Dependent Children], with their college because they need it, $300, $400, according to need.

TLM:

Does the mayor sit on the board?

MAC:

No, the mayor doesn't have anything to do with it. He appoints the people, and they're all people of the city of Boston, residents who are interested.

TLM:

Who heads that board now?

MAC:

Well, at the present time, [Clarence W.] "Jeep" Jones is heading it, the deputy mayor, he's heading it right now. He is acting chairman, he’s not the real chairman, but he is holding it together.

TLM:

You have been a member of the board of directors of the United South End Settlements, where you served as secretary for over ten years.

MAC:

That's right. That's the one that I came on the board because I was president, vice-president, at the time, of the Harriet Tubman House, which is a part of the United South End Settlements. That's how I happened to get involved with it. And I'm still a member of the Board of the United South End Settlements.

TLM:

I see. When did you first get on the board of directors?

MAC:

Well, I guess I must have been on it now about fifteen years, maybe twenty.

[sound of car honking in background]

TLM:

And it was about fifteen, twenty years ago that you were vice-president of the Harriet Tubman House. Was that the same as the Harriet Tubman Mothers, was that before that?

MAC:

That's a part of it. That's a part of that. That's a part of that whole United South End Settlements. Harriet Tubman was one of the buildings, one of the houses, in the United South End Settlements when it was formed. And we had several other houses around there, the one on Union Park, one on Rutland Square, and one on Harrison Avenue, four or five little houses. So they all come together now under one heading in the big new building, Harriet Tubman House.

TLM:

How often do you meet on that board?

MAC:

Well, it's supposed to meet once a month, if I can get there. But they don't insist on me getting there. If I can't, they say I have a place there and just stay there, come when I can.

TLM:

I'm reading from your biography. You've already discussed being the vice-president of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, and the past president of the Northeast Region. So we’ve discussed that. We also...co-organizer of Women in Community Service.

MAC:

That's the Job Corps for Girls, and that was a federal program which was launched here in Boston by five organizations and the one, the Black part of it—the Jewish women, the Catholic women, and the Black women, was the National Council of Negro Women. They didn't have any branch here in Boston, so they asked us if we would assume it, the Women's Service Club, and represent that angle of it. That is how we got involved in that. So we're still active with the Women in Community Service, which sponsors the Job Corps for Girls.

[sound of airplane flying overhead in background]

TLM:

I see. When did the Women in Community Service group come together?

MAC:

Oh, they've been together about...let’s see, during the war, World War II.

TLM:

So for quite a while. And is there a place where that group, that sort of coalition meets?

MAC:

Yes, they now have a headquarters. They had one first in the Department of Labor, out on Huntington Avenue. Now, they're in the building that's owned by the Christian Science Church on Huntington Avenue. They have a suite of rooms... Well they have two or three rooms there, that’s the headquarters for this part. But the formal headquarters is down in the Kennedy building, under the Department of Labor. This is a subsidiary out here. Takes care of the girls. In town they take care of the boys, at the headquarters, but that is where the business emanates from to this section of Roxbury, of Boston.

TLM:

Well, the taking care of the girls, what kind of—was there a training program?

MAC:

Yes, there was a training program set up for the girls who would go off, if they wished, after these. These girls were very disadvantaged, were dropouts, maybe, from school, who were disillusioned, didn't know what they'd want to do. They would be interviewed by certain people who knew how to interview them, trained to do it, and find out if they'd like to go away to one of these training centers for Job Corps. There were several at that time, but they've closed most of them down now. There was one in New Jersey, one up in Maine. There was one out west some place, I forget the name. But they could go to whichever one they wanted to, if they filled the application with their parents' consent, because they're all girls under eighteen.

TLM:

And what sorts of jobs? Oh, they were young.

MAC:

They were trained, they were trained there for all kinds of jobs—typing, secretarial work, even machines, all kinds of things that they were trained in. They were trained in photography, in beauty culture. They had a regular training school where they'd get a little bit of something, enough to come out and perhaps go on further.

TLM:

But there was no connection between this group and the In-migrant Service Program? Or the Homemakers Training?

MAC:

Oh no, no, this was a government program. We were just asked to help with it as a club. And we lended our help, and our members joined in, and they still are working with it. Still working with it.

TLM:

Tell me also about the "William E. Carter Auxiliary Number 16."

MAC:

The American Legion, that is. I joined that organization with my husband when he joined it. Well, I didn't join it right away, but after World War I. He joined it when they formed it, and he was in it until he died. And I'm still in it.

TLM:

So you joined, what, in the, maybe in the 1920s?

MAC:

Oh yes, well way back, twenty-something. I've been in it thirty years, or more than that, I guess. I've been in it ever since I've been out here, forty-seven years, I guess. More than that, fifty. Yes. I worked in it as treasurer and as president and as everything. I just attend when I feel like it. I don't make it a special thing, a dutybound thing to go now. I go when I want to. Pay my dues.

TLM:

How many times a year?

MAC:

About two or three times. I pay my dues.

TLM:

And how large a group is the auxiliary?

MAC:

Well, I guess they've got about fifty members. A small auxiliary.

TLM:

Of various ages, or your generation?

MAC:

Well, of course, they all had to have husbands who were in Vietnam or World War II now, because the World War I are all practically dead, like my husband. They're gone. So it's World War II, like my son, and Vietnam, who are the members now. The women in that age bracket, like I was when I joined. I'm an older one now, more retired one. And they don't expect active participation from me.

TLM:

Is Auxiliary Number 16 membership mostly Black women?

MAC:

All Black women. They might have one or two whites, but all Black.

TLM:

Okay. I see. This is the American Legion, and also it [written biography] says that you served for twenty years as treasurer.

MAC:

Yes, I did.

TLM:

You are a member of Saint Mark Congregational Church.

MAC:

I told you about that. I think you already have that, the Social Action Committee and the Pastor's Club, the Missionary Guild.

TLM:

Okay. Other affiliations: the YWCA.

MAC:

I was a member of the YWCA for many years, and served there with their public relations and so forth, and I came out of their organization, because they were so prejudiced and discriminatory in their practices there, I didn't like it, so I resigned from it. Some years ago.

TLM:

Tell me about that.

MAC:

Well, they had a policy, they didn't care too much about the colored children coming down there getting in the pool.

TLM:

This is the main Y?

MAC:

It was terrible, about thirty years ago.

TLM:

On Arlington Street?

MAC:

So that was all over the country, because they had segregation, and they used it wherever they wanted to use it, those who were on the board. They weren't too open hearted to the Black people, but after some years they have changed.

TLM:

Were you ever on a board there?

MAC:

Yes, I was on it. I resigned from it because of that. I just told you. I resigned from their board, because I didn't want to be implicated. I couldn't make any progress with it, and the one or two other Blacks on there, they didn't see eye to eye, so I got off. And I stayed off until now that they've changed their policy and opened the doors to everybody, and all like that. They asked me to...

TLM:

How long ago was it, how many years ago was it that you got off it?

MAC:

It's about thirty years, maybe more than that. It’s been thirty anyway.

TLM:

And you just left. It was thirty years ago.

MAC:

Yes, I just left and stayed away from it. I didn't bother with it at all. Until lately; they asked me to come now. Of course they've named the Y for me, so naturally I have to be with them now. But I didn’t...and I worked with them...

TLM:

That’s right –now the Y is named...

MAC:

Boston branch.

TLM:

Boston branch is? Which Y is named after you?

MAC:

Clarendon Street, the Y, the Boston branch. The in-town branch. They did that last year, you know. They named it last year you know for me. Changed the name to the Cass Branch. It's now called the Cass Branch.

TLM:

So, and how, was there a big celebration, ceremony?

MAC:

Oh yes, we had a big celebration. I gave you the book they had to read [inaudible]. They had a beautiful celebration there at that time for me. I didn't know it was for me, though, because I worked with them, on their Women '76 program last year, and I helped them as much as I could and got people, gave them ideas on how to do it, and went on the radio with them and worked with them. They were a delightful group of young women. And I never had an inkling that they were working to honor me at the affair which we were giving, this recognition to all these women, my gracious! So I was tickled to death that they were doing it. All the different women, about twenty-five of them or more. When I got there that night of the thing, I said to Topper Carew... He had sent for all those pictures of my family; he said he was going to have an exhibit, and he wanted to put some old-fashioned pictures in it. So when I got there, I said, "Where's the old-fashioned pictures exhibit? I'd like to go look at them." He said, "we’re going to have those after the affair is over." I said, "Oh my goodness, I'll be so tired, I won't even want to look at them." He said, "Oh yes, you will. Yes, you will." So this little girl that's on this, Barbara Dwyer, said, "Oh yes, you will, Mrs. Cass, you'll be very glad you will see them." Barbara Dwyer. One of them. Two or three of them worked with me. So anyway, I went along with them and sat there with the guests, all the different guests. I knew some of them who were being honored. I had a wonderful time. We went into the room for the banquet, and the program went on and everything; so finally when they got down to the real program...when they were presenting all the different citations, the little gifts we had for the people. When they got to my turn, the director, the president of the board said she wanted to make a presentation to me. So she announced that they were going to name their branch Y for me. I couldn't believe it.

TLM:

Oh, what a surprise!

MAC:

Oh, I was spellbound; I couldn’t even—I didn't know what to say; I didn't know what to do; and I began...tears began to go down my eyes, and I was never so... I didn't know what to say happened to me. I was so surprised, shocked almost, because I didn't have any idea that they were doing that, you know, and it was really something great. I worked right along with them every day, and I didn't know what to say to them. But anyway, I managed to say something, thank them. And I couldn't get over it. So then, when they got through with all of that, the next thing I knew was that they put on the screen this whole film about my life, on that screen. Starting with that baby picture, and coming right on up with all my family, everybody, everything, and all those pictures I gave Topper Carew. I wanted to give him a licking, but I couldn't get nowhere near him; I didn't know where he was. So, but anyway, I couldn't get over that. Well sir, I was spellbound with those pictures. And I said, "That's what he wanted with those pictures. Now I know exactly what it is." Well. When the thing was over, I got him and I said, "No wonder you... All of you little sneaks, every one of you, little sneaks." Barbara and, what’s the girl, the girl’s name, Fossberg, and Mary and all of them. I said, "What are you all thinking about?" "Well, we couldn't tell you what we were going to do, you know. If we ever told you, it'd be terrible. You probably wouldn't even come." I said, "Probably I wouldn't. I'd have stayed home." [Laughing] But it was beautiful, that's the nicest thing, oh my goodness I couldn’t believe it. So, after that...”

[End of track, reel 3 side 1]

This audio recording is part of The Black Women Oral History Project, interviews of 72 African American women recorded between 1976 and 1981. With support from the Schlesinger Library, the project recorded a cross section of women who had made significant contributions to American society during the first half of the 20th century. The interviews discuss family background, marriages, childhood, education and training, significant influences affecting narrators’ choice of primary career or activity, professional and voluntary accomplishments, union activities, and the ways in which being Black and a woman affected narrators’ options and the choices made. Interview transcripts and audio files are fully digitized.