Rethinking Incarceration

Imprisoning people isn’t the only way to reduce harm and violence, argue prison abolitionists. They offer alternative solutions.

“I feel like I’m living in a future I could never imagine,” said Angela Y. Davis during a 2022 panel discussion. “I didn’t think I would ever witness it in my lifetime. I feel like I’m in an Octavia Butler novel, in a future where people are (openly) talking about abolition.”

Angela Davis is the United States’ most famous prison abolitionist. She was already organizing around prison conditions and political prisoners in the 1960s, a decade in which the nation’s prisons incarcerated fewer than 200,000 people.

In 1970, she was placed on the FBI’s Most Wanted list after 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson, in an attempt to free his imprisoned brother George, took a judge, a deputy district attorney, and three jurors hostage at gunpoint. One of the guns had been registered in Davis’s name. A nationwide manhunt ensued until Davis was arrested in New York City that October and extradited to California. (She was acquitted at trial two years later.)

That year, the United States incarcerated 196,249 people in state and federal prisons.

Fifty years later, in 2020, the country imprisoned nearly 1.2 million people, a 601 percent increase. That same year, the police murder of George Floyd sparked nationwide protests to defund the police and invest those funds into community resources.

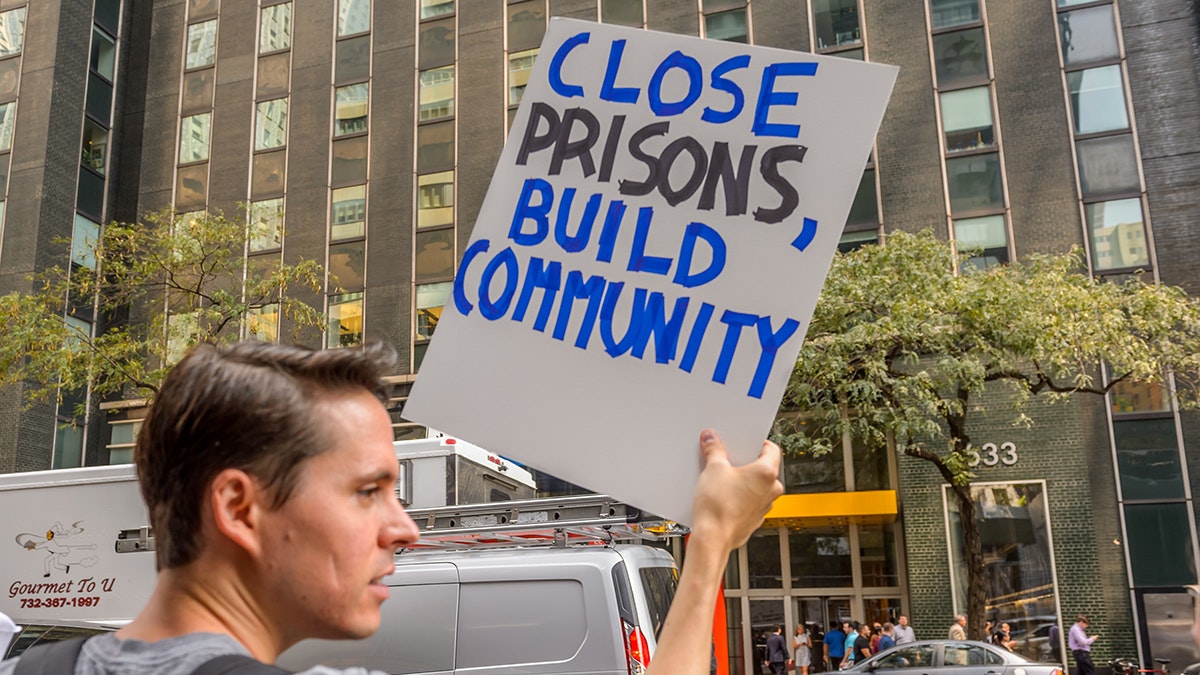

Accompanying those demands came calls for abolition—both a practical organizing tool and long-term goal recognizing that policing and prisons, in all manifestations, cannot be reformed to meet people’s needs and must be eliminated, with resources instead going toward creating and expanding support systems, including medical and mental health care, housing, employment, and education, which would, in turn, reduce harm and violence. Imprisonment does not solve social, economic, or political problems, goes the abolitionist argument. It simply locks away the people hardest hit by these societal failures while failing to build solutions.

“What abolition offers is an invitation for people to work on the building part,” said Beth E. Richie, a professor at the University of Illinois Chicago and one of Davis’s coauthors on Abolition. Feminism. Now. (Haymarket Books, 2022). Abolition, she notes, is about not only freeing people from jails and prisons but also ensuring that they have a place to go that allows them to live freely. “Schools, jobs, health care, and abortion rights are all part of abolition,” she told Radcliffe Magazine.

Demands to defund and abolish are the results of decades of organizing. “Abolition has been percolating for a very long time,” Davis told Radcliffe Magazine. “As a matter of fact, rather than considering abolition a failure or as a nonviable strategy because of the emergence of a global prison industrial complex with its clear connections to racial capitalism, I would argue that this development was precisely the material basis for moving away from a politics of reform to a radical politics of abolition.”

Some of that previous organizing, including Davis’s participation and contributions, are included in her papers now at the Schlesinger Library. Over 300 boxes and folders include Davis’s early drafts of books and extensive documentation of her trial as well as her other writings, letters from incarcerated people, audio and video of past speeches, and documents from organizations she has created and worked with over the decades.

The pandemic has pushed some of the tenets of abolition into public discourse, particularly decarceration or decreasing the numbers of people held in jails, prisons, and other carceral settings (see “The Prison as Petri Dish”). In March 2020, as the novel coronavirus began spreading throughout the United States, public health experts recommended decarceration as a crucial step to stem the spread of COVID-19.

Three months later, after the police killing of George Floyd, broader abolitionist demands—to defund the police and reinvest funds into community support structures—became linked with wider demands for racial justice.

In Abolition. Feminism. Now., Davis and her coauthors Gina Dent, Erica R. Meiners, and Richie remind readers that these demands were built on the foundations of decades of abolitionist theorizing and organizing. “Our work is not simply about ‘winning’ specific campaigns, but reframing the terrain upon which struggle for freedom happens,” they write.

Snapshots of Historical Movements for Abolition

While police and prison abolition recently catapulted into mainstream discussions, the idea is not new. Davis traces the contemporary movement to abolish prisons to earlier movements—to abolish slavery in the 19th century, to end second-class citizenship for Black people in the 20th, and to abolish the death penalty in the 21st.

“The call for abolition during the 1971 Attica rebellion served as a catalyst for many (anti)prison activists to consider abolitionist strategies as especially relevant to a period during which we were experiencing an unprecedented expansion of the prison system,” Davis told Radcliffe, referring to the New York prison uprising in which prisoners took over a prison and issued a series of demands, calling attention to the lack of basic human rights afforded to those behind bars. The uprising ended with 39 deaths and hundreds of injuries after then-Governor Nelson Rockefeller ordered state police to retake the prison.

Even before Attica highlighted abusive conditions, some had already questioned whether prisons should be eliminated. “Should Prisons Be Abolished?” asked a New York Times headline in 1955. Calling the prison an “anachronistic relic of medieval concepts of crime and punishment” that “perpetuates and multiplies” crime, Ralph S. Banay, former head of Sing Sing’s psychiatric clinic, argued for abolition in that article.

During the 1971 Attica rebellion, prisoners took over the prison and issued a series of demands, calling attention to the lack of basic human rights afforded to those behind bars. Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images Contributor

In 1973, two years after the Attica uprising, the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, appointed by the US Justice Department, recommended a 10-year moratorium on prison construction and diverting people from prisons.

That recommendation was not followed. By 1976, the United States had a record number of 250,042 people behind bars, a figure that would be repeatedly eclipsed each year until 2009.

At the same time, organizers fought to stop jail and prison expansion as well as to free those locked inside.

For instance, Davis’s 1970 arrest quickly led to mass mobilizations—both in the United States and abroad—demanding her freedom. Concurrently, organizers started the Women’s Bail Fund, an ad hoc group of feminists dedicated to posting bail for the unfamous women held alongside Davis at the Women’s House of Detention, an 11-story jail in the heart of New York’s Greenwich Village. Inside the jail, women organized and then yelled the names and bail amounts through the window to bail fund organizers on the sidewalk below. Those organizers then raised the money—frequently by canvassing passersby around them—and posted bail, enabling women to be released pending trial. Although that particular fund disbanded when women were moved to Rikers Island, bail funds emerged in other cities.

In 1976, the Prison Research Education Action Project published Instead of Prisons: A Handbook for Abolitionists, which not only dispelled popular myths about prisons and safety but also offered examples of anti-prison organizing and alternatives to imprisonment, including efforts to prevent and address sexual abuse without imprisonment and redirect young men involved in gang activity.

In the ensuing decades, abolitionist organizing continued even as prison populations soared, although, noted Richie, “not everyone called it abolition work.”

Richie recalls organizing to free Kemba Smith, a 24-year-old Black woman sentenced to 24.5 years in 1994. Under the mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines created by the War on Drugs, the judge was unable to consider that Smith had unwillingly participated in her abusive boyfriend’s drug activities out of fear for her life nor that she was seven months pregnant. Organizers—including prison reform groups, radical feminists, and Smith’s sorority sisters—refused to accept that Smith would spend another lifetime in prison and mounted a prolonged campaign for her freedom.

During the campaign, recalls Richie, “We were able to link understandings of race, class, and heteropatriarchy.” Six years later, in 2000, then-President Clinton granted Smith clemency, or a sentence reduction enabling her release.

Continuing to highlight the connections between race, class, heteropatriarchy, and criminalization, Richie and other women of color created the INCITE! network to organize against gender-based violence and state violence, such as policing and incarceration, faced by many women of color.

INCITE’s analysis has continued to influence others, including local and national campaigns to free domestic violence survivors arrested for self-defense and, in 2016, the creation of Survived & Punished, a national network to free imprisoned abuse survivors.

Other groups explicitly centered abolition as their goal. In 1998, abolitionist organizers and educators, including Davis, organized Critical Resistance—a national gathering of individuals and organizations interested in radical approaches to challenging prison expansion. Thousands attended that initial three-day event. Attendees formed grassroots chapters across the country, connecting with other groups to close prisons, stop jail construction and expansions, and build community resources. The group also worked to shift the discourse and vocabulary about incarceration in the United States.

“When Critical Resistance was created in 1998, it was specifically in response to the then new conditions produced by the confluence of the collapsing welfare state, the failure to address structural racism, and the transformation of the punishment industry (along with healthcare and other fields) into profitable enterprises,” Davis told Radcliffe. “In sum, I think the rise of abolitionist theories and politics reflected an awareness of what was needed specifically at that historical moment.”

The organization Critical Resistance was formed in 1997 to challenge the prison industrial complex. This flyer, from the Angela Y. Davis Papers, publicizes its first national conference, in 1998. Photo by Kevin Grady

Abolition in Action

What does abolition look like in action? In Massachusetts, it looks like Reimagining Communities, an initiative spearheaded by formerly incarcerated people to identify and create safety without incarceration.

“We were tired of reimagining prisons,” explained Andrea James, a cofounder of the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls and lifelong Boston resident who took part in the Radcliffe discussion “Decarceration and Community: COVID-19 and Beyond.” “We don’t believe the system will dismantle itself.”

In Boston, organizers began by asking, “What are the policies developed by formerly incarcerated people that would decrease the numbers of people in prison?”

They brainstormed solutions—which included decriminalizing drugs and sex work, policies to release the infirm and elderly from prison, voting access, clemency for women with lengthy prison sentences, laws diverting parents and primary caretakers from prison, and a moratorium on new jails or prisons.

“We don’t have all the answers yet—and these answers are going to come from the communities most affected,” James said.

Understanding that, in 2020, organizers began convening community dinners and town halls in neighborhoods hard hit by violence, poverty, and incarceration to discuss concrete ways to create safety and address harm. “We’re helping neighbors understand that not sending people to prison or jail is not about not taking accountability,” James explains. These conversations encouraged residents in communities hardest hit by poverty, racism, interpersonal violence, and state violence to identify solutions along with the resources needed to put those solutions into practice.

Residents suggested reallocating money from police and prisons to fund alternate response teams for mental health crises, a basic guaranteed income program for women being released from prison, and better-resourced participatory defense, a community organizing model in which people facing criminal charges—and their loved ones—learn to participate in their own defense.

But, cautions James, “Communities are not monolithic,” and different communities will propose different solutions.

“Angela Y. Davis has lived her life lending her voice to those who could not speak for themselves,” said Kenvi Phillips at the time of the acquisition, when she was the curator for race and ethnicity at the Schlesinger Library. “Her decision to preserve her papers with the Library ensures that she will perpetually speak against inherently unequal power structures. We are thrilled to be part of the process of carrying the voice for the voiceless to future generations.”

Davis’s papers at the Schlesinger document historical and contemporary organizing in the United States and abroad—much of which might otherwise be forgotten. “I always try to shift attention away from myself as an individual and toward the work of organizations, movements, and communities,” Davis told Radcliffe Magazine. “I hope this is the dynamic that characterizes the reception of my papers.”

Watch Angela Davis talk about Critical Resistance and the prison industrial complex in 1998.

Victoria Law is a freelance journalist who focuses on the intersections of incarceration, gender, and resistance. She is the author of Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women (PM Press, 2009) and “Prisons Make Us Safer”: And 20 Other Myths about Mass Incarceration (Beacon Press, 2021) and the coauthor, with Maya Schenwar, of Prison by Any Other Name: The Harmful Consequences of Popular Reforms (The New Press, 2020).