Scenes from a Manuscript Curator's Life

Following her recent retirement, Kathryn Allamong Jacob shares unforgettable experiences—and lessons learned—from her decades as the Schlesinger Library’s Johanna-Maria Fraenkel Curator of Manuscripts.

Climbing into a dim barn loft to discover a thick layer of guano covering dozens of footlockers and the hundreds of little bats that produced it dangling from the rafters. Helping a blushing young mover, excited to be at Harvard and now bewildered, pick up dozens of sexually explicit videos that had spilled from a broken carton as he wheeled a new collection to the Library. Watching a donor gather eggs from his chicken coop and tomatoes and herbs from his garden on a lovely fall day to whip up a perfect omelet for our lunch. The tea is rarely decaffeinated. “The dog is very friendly” is not always true. Sherry does go bad.

These are collecting adventures and lessons learned during 20-plus years of carrying out the curator of manuscripts’ main task—growing the Library’s manuscript collections. The process is a lot like gardening. Cultivation includes proactively reaching out to key players in targeted areas and enlisting the help of scholars and the Library’s many friends. Seeds planted may blossom right away or they may not flower for years, sometimes decades.

Another way the Library grows is through offers that arrive out of the blue by e-mail, call, letter, or the unexpected visitor at the front desk with a suitcase full of diaries. I enjoyed every aspect of the curator’s job, but I loved working with donors—and with these particular donors, the ones who sought us out, most of all. It’s work that can be intensely intimate and profoundly moving.

What motivates widowers, daughters and sons, siblings, parents, and others to offer up the papers, often very personal, of mothers, wives, daughters, even their own? Sometimes it’s dispassionate pragmatism, like the young woman from California, in Cambridge for three days to empty the apartment of a deceased great-aunt she’d never met: “Her friend said you might take old files labeled National Woman’s Party. Come now or they go in the dumpster.” (We went.) More often, the decision to call/e-mail/write/visit is an emotional one, motivated not just by downsizing or a move but by love, grief, guilt, pride, settling old scores, a bid for immortality, or several reasons intertwined.

Two mothers donated the papers of their deceased daughters, both doctors—Nancy L. Caroline and Linda J. Laubenstein—with the hope that their collections would not only keep their legacies alive but also guide other young women contemplating careers in medicine. The daughter of Helen Reed Atwood ’39 scattered rose petals inside the carton of her mother’s papers and wrote that the gift was a way “to keep my mother alive.” The Jane Florence Levey papers, donated by her sister after Levey’s death at 39, include communications among the FOJ (Friends of Jane), a network of 100+ people who loved and supported her and each other through her illness.

Nancy Caroline was a medical doctor and a pioneer in the training of paramedics and emergency medical technicians. She worked in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and in Israel and Africa. Nancy L. Caroline Papers/Schlesinger Library

Children have felt that their deceased mothers had lived in the shadows of their prominent husbands long enough and deserved collections of their own rather than as “wife of….” Other sons and daughters—still wresting with their mother’s coldness or smothering attention or belittling or abandonment years after her death—have wanted her diaries and letters open to researchers.

Recognizing the research value of a 30-year run of diaries, the historian G. D. (Don) Lillibridge offered us those of Florence Julie Lillibridge, his late wife of nearly 60 years. He wanted her to tell her story in her own words. He couldn’t, however, read those words: the diaries were written in Gregg shorthand. At his expense, he had them all transcribed, with the transcriptions sent directly to us. “Let the chips fall where they may,” he said, although he hoped deep down that Flo had loved him until the end. (She did.) Other collections come with a different story. Widowers have admitted to infidelity, to being “an overbearing jerk,” to killing dreams, and they see donating their wives’ papers as a way to apologize, belatedly.

Sometimes multigenerational family collections are offered up because the very last family member who cared about them has died. The dustbin looms. But often it’s the opposite—family members care very much. The Ames Family Historical Collection spans 250 years, many generations, and the whole sweep of westward expansion. Mary Lesley Wolfe, for decades the conscientious custodian of this large (101 linear feet) collection, hired an archivist to organize it and did her best to make it available to researchers, but she knew its riches would be better mined in an official archive rather than in a storage facility in Boulder. After a scouting mission by her daughter—and with the advice of historians, the family’s deep roots in Massachusetts, and the strong women in every generation in mind—she chose the Schlesinger Library.

While Wolfe understood the importance of her family’s collection, other donors are motivated by a sense of their own place in US history. After a 40th reunion, a group of former Peace Corps volunteers tentatively asked whether the Library might want their papers. Although modest about their own accomplishments, they were proud of what they had done collectively. In their late teens and early 20s, some never having traveled outside of their states, they had answered President Kennedy’s call to join the new Peace Corps, and, in 1968, landed in Afghanistan, in the vanguard of the campaign to eradicate the scourge of smallpox from the world. (Victory was declared in 1979.) They could go, they explained, where men could not. Their collection, still growing, includes their training manuals, letters home, diaries, photographs, and several tiny glass vials of desiccated smallpox vaccine.

While the answer to the vaccinators’ question was an enthusiastic “Yes,” we don’t—we can’t—accept every collection proffered, no matter the motivation. With every linear foot of documents, even those that are donated, as a majority are, the Library incurs a steep price for processing, storage, and providing access. The yardstick by which potential acquisitions are measured is research value: does this material further the Library’s mission to document the history of women in America? Sometimes the answer is no. That’s a difficult message to convey—and an even harder one for many to hear.

After a 40th reunion, former Peace Corps volunteers who traveled to Afghanistan in 1968 to help vaccinate women against smallpox approached the Schlesinger about donating papers and ephemera. Here, tiny glass vials hold desiccated smallpox vaccine from that effort. Photo by Kevin Grady

Collections that measure up have arrived in pillowcases, in trunks, and in beautifully organized archival cartons. Some have included spider egg sacs and powdery mold. But however they arrive, the fact that they will reside in the Schlesinger Library, as those rose petals attest, means a great deal to the donors. One donor sent five pounds of Hershey’s Kisses. Ten members of the Ames/Lesley/Lyman family encircled Wolfe as she signed the donor agreement in Boulder. Later, the moving van driver sent Wolfe photos each night of the truck parked under bright lights on its way to Cambridge. Donors have planned family vacations around delivery of a collection and included the news in their holiday letters. One day, the family of a local woman, who I knew was ill and with whom I’d been working on donor documents for months, called. Could I bring the deed of gift right away? I was there within the hour. With enormous effort, she raised herself up and signed her name. She died just hours later. I will never forget her or her lesson in how important the act of donation can be.

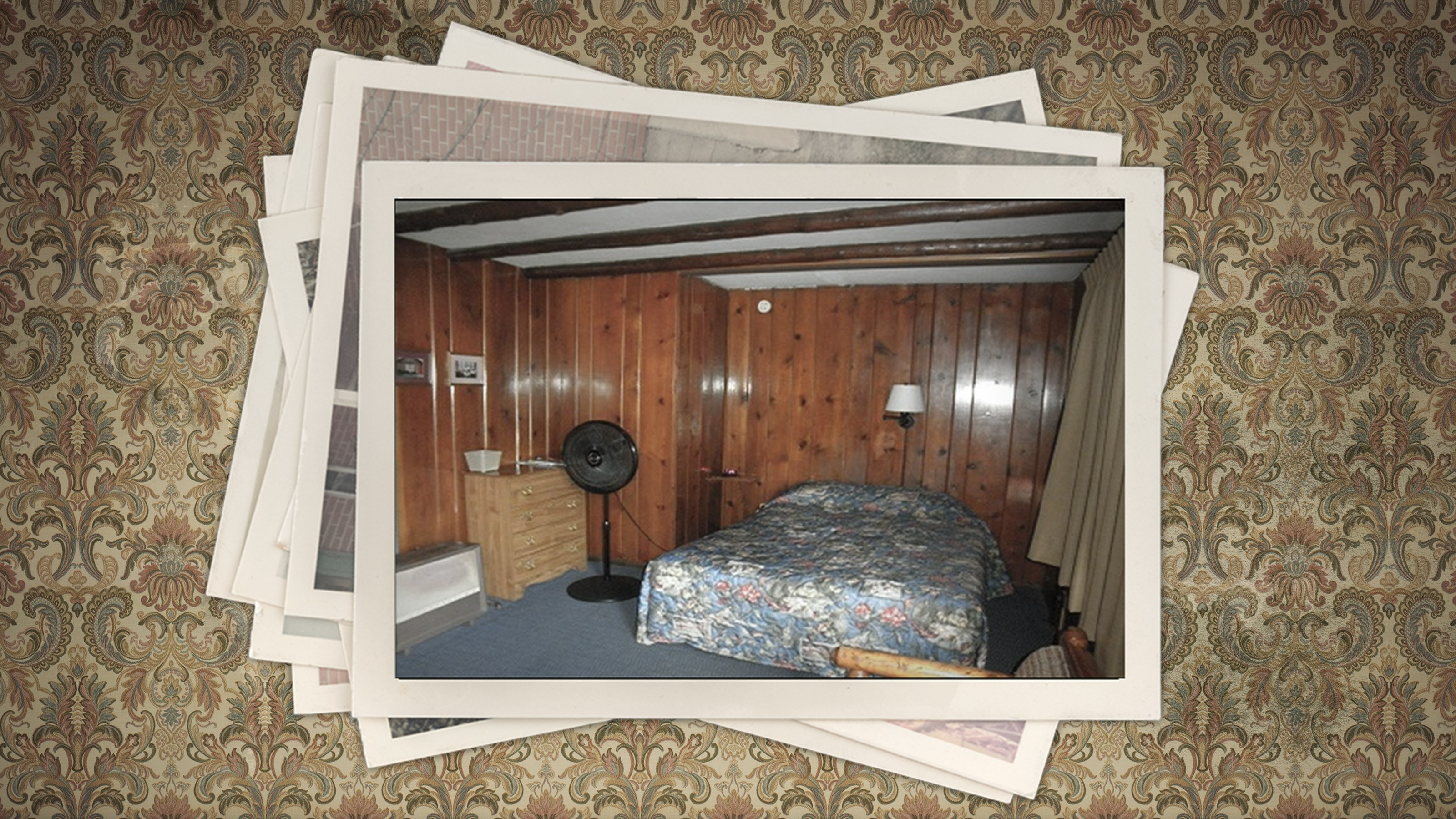

I’ve loved working with donors. From standing on a table in the mess hall and being serenaded by 200 campers at Camp Walden to being warned upon check-in at the Foot of the Mountain Motel in Boulder not to keep any food in my room (“You don’t want a bear coming through that picture window”—I stowed everything edible, even my toothpaste, in the trunk of my rental car), I’ve loved almost every collecting adventure. I will probably always scan the obituaries, and sometimes I’ll see the name of an extra special donor, like the poet Jean Valentine, that will bring tears. All of them have donated collections with the potential to enrich scholarship, and all of them have enriched my life.

When Jacob arrived at Camp Walden in Denmark, Maine, to collect their records, she found them in a bat-filled barn attic—but she was also serenaded by 200 campers in the mess hall. This photo, taken in 1955 and collected during that visit, shows the camp’s beach and lakefront. Camp Walden Records/Schlesinger Library

To see more extraordinary items from the Schlesinger's collections, a number of which Jacob helped bring to the Library, please visit 75 Stories, 75 Years: Documenting the Lives of American Women at the Schlesinger Library.